Reframing the Past

-

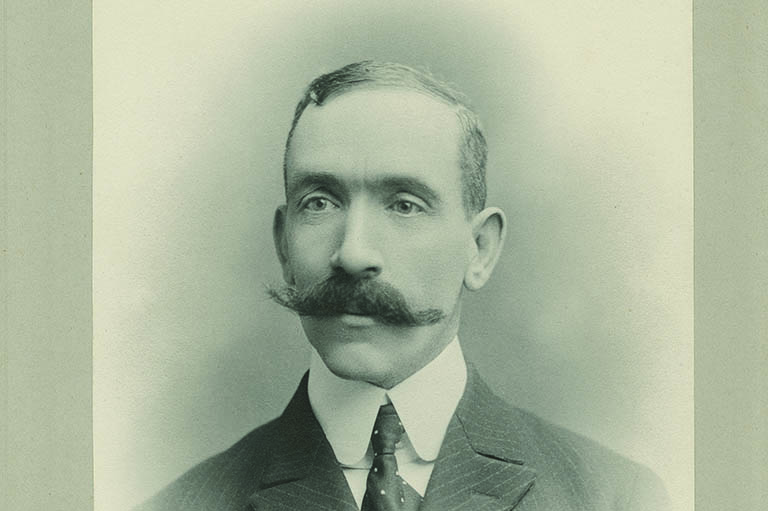

NWMP inspector Christen Junget, officer in charge of the Yorkton district from 1899 to 1913, poses in front of St. Andrew's Church, Yorkton.Courtesy of Keith McLaren

NWMP inspector Christen Junget, officer in charge of the Yorkton district from 1899 to 1913, poses in front of St. Andrew's Church, Yorkton.Courtesy of Keith McLaren -

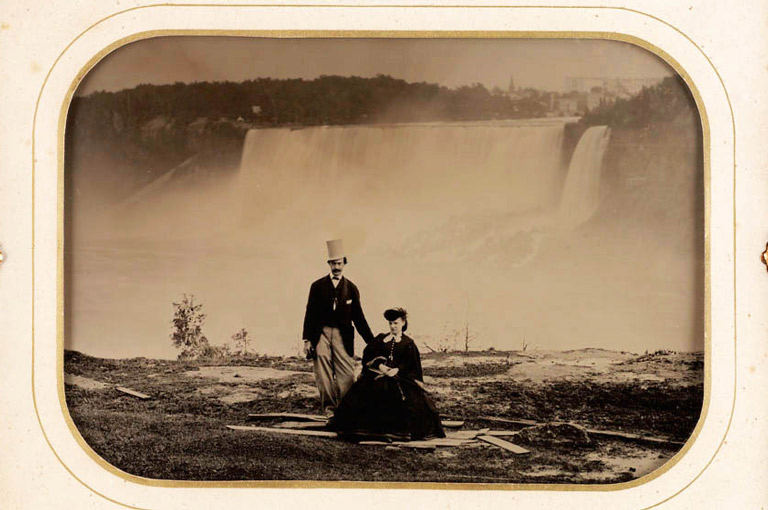

Chloe Ann Burkell, holding a camera, poses with a First Nations woman doing beadwork. The photo was taken near Yorkton at the Solomon Brass family encampment.Courtesy of Keith McLaren

Chloe Ann Burkell, holding a camera, poses with a First Nations woman doing beadwork. The photo was taken near Yorkton at the Solomon Brass family encampment.Courtesy of Keith McLaren -

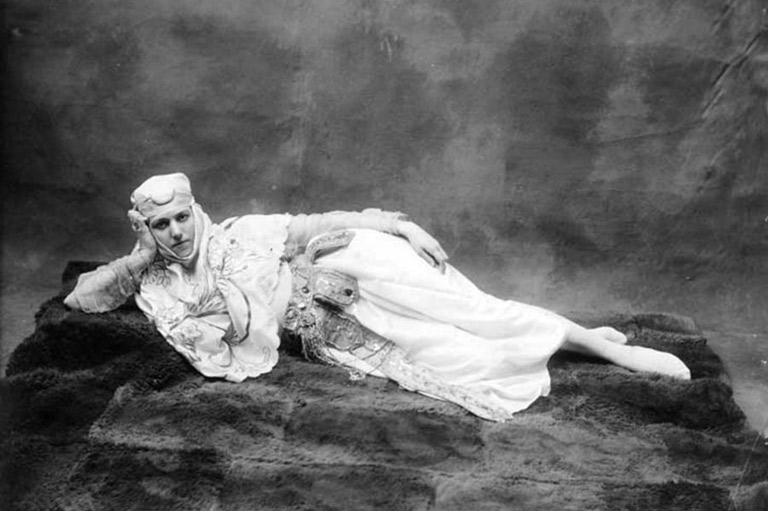

A barefoot Doukhobor woman wears a traditional dress while posing at a farming commune northeast of Yorkton.Courtesy of Keith McLaren

A barefoot Doukhobor woman wears a traditional dress while posing at a farming commune northeast of Yorkton.Courtesy of Keith McLaren -

A wooden Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the Yorkton Region.Courtesy of Keith McLaren

A wooden Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the Yorkton Region.Courtesy of Keith McLaren

Chloe Ann Burkell passed away long before I had a chance to form any first-hand impressions of her. All I knew of her came from photos and stories told by my mother.

Chloe, my grandmother, became forever fixed in my memory as she appeared in her later years — a snowy-haired, beatific matriarch with soft features and kind eyes. It never occurred to me to dig behind the surface and find out more about her life.

Her role as mother and grandmother seemed to be what mattered most. From my mother, I knew that Chloe had been a strong-willed and resourceful woman, generous with her time in helping others. But it was my grandfather, with his larger-than-life personality and near-legendary career with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who was the dominant presence in our family.

It was not until I found a photograph album of Chloe’s, when clearing up my mother’s estate, that I began to see my grandmother in a different light. Through these images I began to truly realize the depth of her character and to appreciate the record she made of her young life in Yorkton, before and after it became Saskatchewan.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The album held images of her work as an amateur photographer from 1900 to 1913. It contains several hundred photos, and, at first glance, it appears to be a typical record of the period, containing faded black-and-white images of family members and friends.

However, her work also has a more exploratory range of subject matter, and it becomes clear that she was an astute observer of her environment and of daily life.

With a dedication unusual for an amateur photographer in the early 1900s, she photographed every building and street scene in the community, homesteads and working farms, and, most often, the people who inhabited the town and the surrounding area: First Nations and Métis families, barefoot immigrant women in traditional dress, homesteaders and their log-and-sod homes, as well as community celebrations, crowds attending a local fair, pony races, and North West Mounted Police (NWMP) officers escorting crowds of Doukhobor men through town.

Chloe was a newcomer to the prairies, arriving with her family from Ontario in 1900 to homestead just northeast of Yorkton. Born in 1880, she would have been on the cusp of adulthood when she arrived in this small, bustling community.

Almost certainly she, along with her family, would have experienced culture shock, coming as they did from a well-established and prosperous farming community. In the period between 1896 and 1911, the Canadian government encouraged tens of thousands of non-English-speaking settlers from eastern Europe — including Ukraine and Russia — to populate and farm the prairies.

Meeting these settlers, as well as meeting members of Métis and First Nations communities, and immigrants from the United States, would have made for a curious experience for a young woman fresh from Central Canada.

She met my grandfather Christen Junget soon after arriving in Yorkton, and they married in 1903. A young Danish army officer, Christen moved to Canada in 1899 specifically to join the NWMP. Like Chloe, he would have experienced a huge cultural change, coming from his native Denmark to the Canadian West. His linguistic skills in French, German, and Danish were considered assets in dealings with new immigrants, particularly those from eastern Europe.

So, almost immediately after training in Regina, he was posted to the Yorkton district.

NWMP officers at this time were expected to maintain contact with new settlers and homesteaders to ensure they were coping with the rigours of frontier life. It would not have been uncommon for a wife to accompany her husband on his rounds during this period. This would account for some of the more remote farming and homesteading locations in Chloe’s images.

It’s evident to me that Chloe relished the experience of taking photos. I can’t say with any certainty that she was aware that she was documenting a part of Canadian history, or whether she simply took photos of subjects that interested her. Whatever her motivation, she left us with a surprisingly detailed pictorial record of life in and around a small prairie town in the first decade of the twentieth century. Besides being a revelation of who my grandmother was at a formative time in her life, this album has given me the opportunity to see through her eyes life on the Prairies as it unfolded more than a century ago.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!