Face to Face with Dinosaurs

Victoria Arbour felt her pulse quicken. The indentations in the rock at her feet were clearly dinosaur tracks, made in what eons ago had been soft mud. Arbour, the curator of paleontology at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, was doing fieldwork near Tumbler Ridge in northeastern British Columbia in July 2023 when Charles Helm of the Tumbler Ridge Museum suggested she take a look at some unusual footprints. They resembled those of an ankylosaur, a spiky armoured dinosaur often described as a walking tank. But unlike any ankylosaurs found to date, these prints had three toes instead of four on the back legs and five digits on the front legs. Could this be a new species?

“I was super excited,” recalls Arbour, “since ankylosaurs are my favourite group of dinosaurs to work on.” In a study published in 2025, the research team led by Arbour confirmed that this was indeed a new species; they named it Ruopodosaurus clava (tumbled-down lizard with a club), referencing both the mountains near Tumbler Ridge and the heavy tail club that ankylosaurs could swing at predators. The tracks date back about 100 to 94 million years, during the middle of the Cretaceous period, 145 to 65 million years ago. It was previously thought that ankylosaurs might have disappeared during this time, but Ruopodosaurus fills the gap in the fossil record.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

“We’re discovering more new dinosaur species than ever before,” reports Caleb Brown of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alta. The Tyrrell is the foremost dinosaur museum in Canada — if not the world — with a collection of 160,000 fossils, many of them sourced from the nearby Alberta badlands. And more are being found every year.

Why the current paleo boom? Brown cites such factors as more people in the field doing work in new geographical areas and international co-operation from countries like China, where paleontological studies have taken off. “And, quite simply, we’re looking at things with fresh eyes,” he says. “For decades, we thought that only dinosaur bones were well preserved. Now, we’re looking at fossils of dragonflies and footprints in ancient trackways.” It’s an approach that is furthering our knowledge of these astonishing prehistoric creatures.

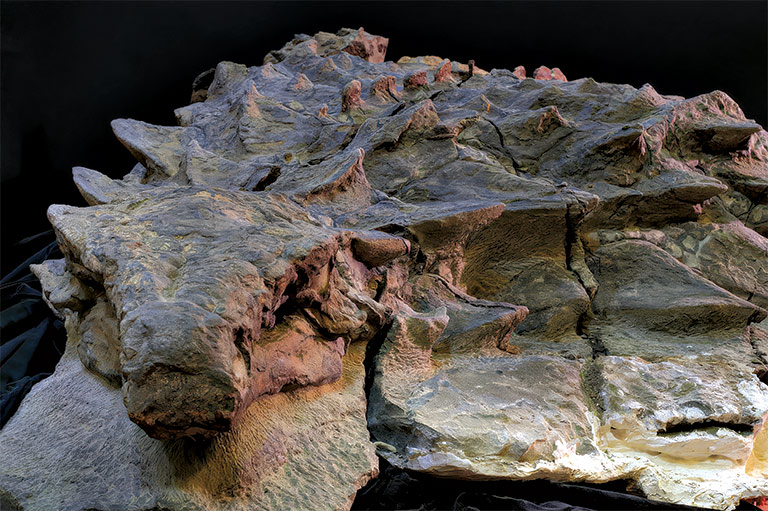

The trackways that led to Arbour’s discovery also show that nodosaurs, a related armoured species, coexisted with ankylosaurs at this time. Similar in size, nodosaurs had the same bony armour plating as ankylosaurs, though they had smaller triangular-shaped heads and fierce-looking spikes protruding from their shoulders. And there was no club on their flexible tails. A nodosaur on display at the Tyrrell museum is so astonishingly well preserved that it has become popularly known as “the dinosaur mummy.” “This is the closest you’ll ever get to being face to face with a dinosaur,” says Brown, noting that its effect on museum-goers can be profound.

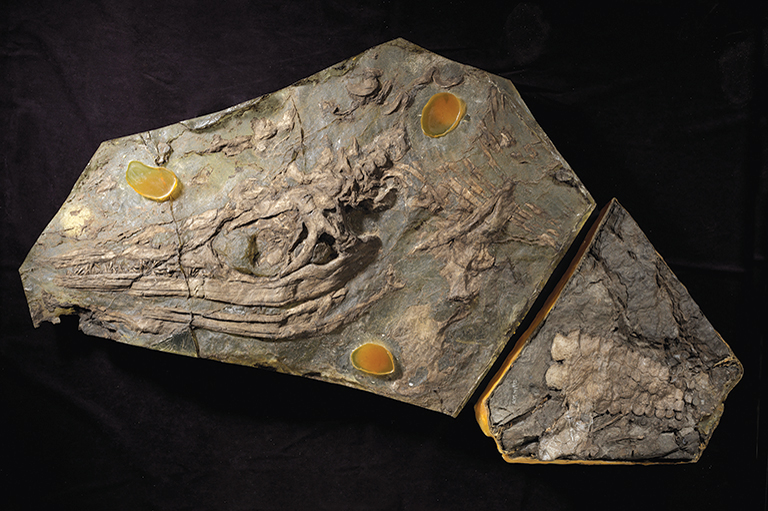

The nodosaur was discovered by accident in March 2011 at a Suncor oilsands mine north of Fort McMurray, Alta. Shovel operator Shawn Funk was using a massive excavator to dig down to the bitumen-rich oilsands when he suddenly unearthed a large, flat stone with a kind of polka-dot pattern. Funk had recently visited the Tyrrell museum, and to him, this stone resembled fossils he had seen there. Work stopped, photos were sent to the Tyrrell and, two days later, the museum’s curator of dinosaurs, Donald Henderson, and technician Darren Tanke arrived at the site. Henderson suspected the fossil might be from a marine reptile since the oilsands had once been covered by a shallow inland sea where long-necked plesiosaurs and dolphin-shaped ichthyosaurs once thrived. He was surprised, then, when Tanke identified the specimen as an ankylosaurian dinosaur and concluded that the animal had become bloated after death and floated down a river into the inland seaway that once divided the continent.

Advertisement

It would take nearly three weeks to retrieve the bulk of the specimen and transport it to the Tyrrell. There, technician Mark Mitchell began the meticulous work of freeing the nodosaur from the marine rock encasing it. After 7,000 hours spread over five-and-a-half years, “the best-preserved armoured dinosaur ever found” was revealed. It was named Borealopelta (northern shield), with the species name markmitchelli, in recognition of Mitchell’s painstaking work.

Most dinosaur specimens found with skin and soft tissue have been flattened during fossilization, but Borealopelta is fully three-dimensional, looking much as it did in life 112 million years ago. When the nearly 1.5-tonne nodosaur sank upside down to the sea floor, it was buried in soft mud, which over millennia, turned into adamantine marine rock, preserving the creature with minimal distortion. Also preserved was a soccer ball-sized stomach mass revealing the herbivore’s last meal (fern fronds, likely foraged in a burned-out coniferous forest since traces of charcoal were also found).

Perhaps the most exciting discovery of all was that molecules in its fossilized skin could possibly determine the colour of Borealopelta. For years, dinosaurs were depicted with dull brown or grey skin, but many paleontologists now believe they may have been brightly coloured like birds or modern lizards. Yet, only recently have they started to find proof. At the forefront of the new field of paleo colour studies is a research team at the University of Bristol in the U.K. A 2017 study by this group determined that Sinosauropteryx (Chinese lizard wing), a 1.25-metre-long creature covered in downy fuzz, had a ginger-and-white striped tail. The Bristol group also detected what’s known as “countershading” on Sinosauropteryx, meaning it was darker on top and lighter beneath, which helped camouflage it from predators. Evidence of countershading was also found in molecule samples of Borealopelta sent to the Bristol team, which determined that the nodosaur had a reddish-brown colour on its back and head, with a lighter tone on its belly. This indicates that even this heavy armoured creature was vulnerable to attacks from carnivores such as Acrocanthosaurus (high-spined lizard), the apex predator of the Early Cretaceous.

It would take another 40 million years before every child’s favourite scary dinosaur, Tyrannosaurus rex, would become the dominant predator in North America. Only three T. rex skeletons have been discovered in Canada; “Scotty,” the largest and most complete of them, was located near Eastend, Sask., in 1991 and is now the star of Regina’s Royal Saskatchewan Museum. The two others were found in Alberta.

A recently identified early cousin of T. rex — from 79.5 million years ago — is the oldest tyrannosaur ever found in Canada and one of the oldest in the world. On a hike in 2008 along the Bow River near Hays, Alta., rancher John De Groot and his wife, Sandra, both paleontology enthusiasts, found two fossils from what looked like a dinosaur’s jaw. “We knew it was special,” John told Sci.News in February 2020, “because you could clearly see the fossilized teeth.” When a Tyrrell paleontologist gave a presentation at a local school in 2010, the De Groots showed him their finds, which the expert immediately identified as belonging to the upper and lower jawbone of a tyrannosaurid. John led a team from the Tyrrell museum to the site where he and his wife had found the fossils and additional skull fragments were recovered. After the De Groots presented the bones they had found to the Tyrrell, they were identified as coming from a Daspletosaurus (frightful lizard), a tyrannosaur at the top of the food chain 77 to 74 million years ago.

In 2018, Jared Voris, a graduate student at the University of Calgary, noted that the specimen found by the De Groots differed from Daspletosaurus and other tyrannosaurs. The shape of the cheekbone and ridges along the upper jaw indicated a creature that had never been seen before. It was dubbed Thanatotheristes (reaper of death) — from Thanatos, the personification of death in Greek mythology — and given the species name degrootorum in recognition of John and Sandra De Groot’s discovery. This predator had a large jaw with more teeth than most tyrannosaurids, which were serrated like steak knives for effective ripping through flesh. It was as long as a small bus, though its likely descendant, T. rex, would grow to almost twice its size and have the strongest bite force of any land animal.

Second only to T. rex in the pantheon of famous dinosaurs is Triceratops, the best-known member of the ceratopsians, a family of huge horned and frilled dinosaurs that lumbered across western North America during the Late Cretaceous. We know they travelled in herds due to the many bonebeds found in Alberta. Centrosaurus were cousins of Triceratops; as many as 300 to 1,000 of these creatures can be found in each of the three bonebeds in Dinosaur Provincial Park (168 kilometres southeast of Drumheller). What would cause so many of these massive animals to be killed together? This has long puzzled paleontologists, but current belief holds that the Western Interior Seaway was subject to violent typhoons and even tsunamis that could have drowned whole herds.

Of the 40 ceratopsian species identified to date, more than half have been discovered in Alberta. They’re divided into two large groups: centrosaurs and chasmosaurs. Centrosaurs have longer horns on their noses, shorter horns on their brows and fewer showy frills, whereas chasmosaurs (like Chasmosaurus itself) have shorter nose horns, longer horns on their brows and more-extravagant frills. Centrosaurs died out about 71 million years ago, while chasmosaurs lasted until the mass extinction that ended the Cretaceous 66 million years ago.

In 2015, Brown and Henderson unveiled a new ceratopsian species with characteristics of both groups. The skull of this creature was discovered in 2005 by Calgary geologist and dinosaur hunter Peter Hews, who spotted a triangular fossil and hornlike shape sticking out of a bank of the Oldman River in southern Alberta. He sent photographs to the Tyrrell museum, where it was determined that it looked like the fossil of a ceratopsian. It would take 10 years to excavate, prepare and research this specimen, during which it was nicknamed “Hellboy” for its resemblance to the comic-book character and because it was “hell” to remove it from its rock encasement. Brown and Henderson determined that Hellboy was a chasmosaur from 68 million years ago but had short brow horns and a shortened frill similar to centrosaurs, which were, by then, extinct. Its frill is reminiscent of a royal crown, so Brown and Henderson gave it the official name Regaliceratops (royal horned face), with the species name peterhewsi in honour of its discoverer.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Another intrepid fossil hunter, Wendy Sloboda, is invoked in the name of the ceratopsian, Wendiceratops, that she discovered in 2010. David Evans of Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum describes Sloboda as “one of the best dinosaur hunters in the world” and “basically a legend in Alberta.” As a teenager growing up in Warner in southern Alberta, she discovered fossilized eggshells in 1987, which led Philip Currie and other scientists to uncover nests of duck-billed hadrosaurs, some with preserved embryos inside the fossilized eggs. Since then, Sloboda has combed the dusty rocks of the Alberta badlands, as well as sites in Argentina, Mongolia, France and Greenland, and discovered more than 300 important specimens — many of them new species like the ceratopsian that bears her name. Research by David Evans and Michael Ryan of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History determined that Wendiceratops was a centrosaur that lived 79 million years ago and had an elaborate frill, particularly for an early ceratopsian. Today, the restored skeleton is on display at the Royal Ontario Museum — and an illustration of its head is now proudly tattooed on Wendy Sloboda’s arm.

“Big Sam” is the moniker applied to a Pachyrhinosaurus head excavated in 2024 by the Philip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum in Wembley, Alta. A centrosaur from more than 70 million years ago, Pachyrhinosaurus (which means “thick-nosed lizard”), has sometimes been called “the ugliest dinosaur” since it has a big, bony lump, known as a “boss,” on its nose instead of a horn and more bony humps over its eyes. It was retrieved from the Pipestone Creek bonebed near Grande Prairie, Alta., which Emily Banforth, a paleontologist at the Currie museum, describes as “one of the densest dinosaur bonebeds in North America. It contains about 100 to 300 bones per square metre.” Extracting Big Sam from a huge cluster of bones was a challenge, but the skull was eventually wrapped in burlap and encased in plaster before being transported to the museum, where it’s now being prepped for further study and eventual display.

And so, the paleo boom continues. Students enter the field with dreams of uncovering new species. But how many dinosaurs are left to be found? “Look how many species of birds there are today,” says Brown. “Dinosaurs dominated the landscape for over 200 million years. I think we’ve barely scratched the surface.”

-

Researchers excavating the “Big Sam” Pachyrhinosaurus head in 2024Image Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, AB

Researchers excavating the “Big Sam” Pachyrhinosaurus head in 2024Image Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, AB -

The skeleton of Pachyrhinosaurus from the Pipestone Creek bonebedImage Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, AB

The skeleton of Pachyrhinosaurus from the Pipestone Creek bonebedImage Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, AB -

A model of Pachyrhinosaurus at the Royal Tyrrell MuseumImage Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, AB

A model of Pachyrhinosaurus at the Royal Tyrrell MuseumImage Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, AB

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement