The Thistle and the Cross

On November 14, 1687, Marie Hiroüin de la Conception died at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital in Quebec. She had served there as an Augustinian nun and nurse for thirty years. According to the obituary preserved in manuscripts at the Hôtel-Dieu’s archive, her sisters at the convent admired her simple obedience, her respectful deference toward her superiors, her mildness, her patience, and her equanimity.

If these qualities match what you are expecting to find as praise for a seventeenth-century nun, you are understanding the obituary as its authors intended. Then as now, an obituary is not simply an account of a person’s life. It tells a story that is meant to honour the deceased individual and support her community. The authors of this obituary were writing in a monastic context, so it is not surprising that they chose to emphasize virtues of humility. The writers also included less conventional details, and these hint at ties that extended beyond the cloister to political and religious developments stretching across the Atlantic.

The obituary of Marie Hiroüin takes us into questions of what it meant to be Scottish in the seventeenth century, of how religious reformation shaped political allegiances in both Europe and North America, and of why missionaries were so important to colonial efforts in New France. It illustrates how the life path of a single individual can be shaped by the whims of kings and by sweeping geopolitical movements. And it hints at an ancestral connection between a humble nursing sister in Canada and the highest noble houses of Europe.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Hiroüin came to Canada twice. She first arrived around 1643, sent by the Augustinian nuns of the Hôtel-Dieu in Dieppe, France. Her destination was the small Jesuit mission of Sillery on the banks of the St. Lawrence River, about eight kilometres upriver from the town of Quebec. Sillery had been founded at a site known to the local Indigenous people as Kamiskouaouangachit — a long-favoured seasonal fishing spot for Algonquians of the St. Lawrence valley. At the time of the mission, the site was inhabited by perhaps forty Indigenous families year-round, with many others visiting regularly.

It would have been a challenging place for the teenaged Hiroüin to live and work. She had come from an institution praised by a Jesuit in Canada as “one of the best-run in Europe.” She arrived at a small stone structure that served as both a hospital for local Indigenous people and a dwelling for six Augustinian sisters. Not only was the hospital outside the main French settlement at Quebec, it was also separated by a hill — and located one cove over — from the chapel and Jesuits’ house that formed the religious core of the Sillery mission.

Hiroüin was “not able at that time to accommodate herself to the manners of the country, which obliged her to return to France,” as the Annales of the Hôtel-Dieu put it, so the nuns kept her on as a boarder until she could sail back across the Atlantic to France. She returned to Canada in 1657, this time as a professed nun, sharing the passage with her friend Catherine le Contre de Sainte Agnès, another nun from France. The ocean crossing was an adventure in itself. Her ship, the Saint-Sebastien, was pursued by pirates for about a day after it left shore. After its escape, the crossing was fairly quick for its time: only about fifty-six days at sea. By then, the Hôtel- Dieu hospital had been moved from Sillery into the town of Quebec, so that is where Hiroüin went. She remained at the hospital for the rest of her life, until her death in 1687 at the age of sixty-one.

The first thing that someone reading Hiroüin’s obituary might wonder about is the surname of its subject: “Hiroüin” does not look typically French. A sentence a few lines down suggests why. It says she was the “daughter of a noble Scotsman who had become a refugee in France with his family.” The seeming strangeness of the subject’s name is probably the result of a scribe writing Scottish sounds using French orthography. If we try to pronounce Hiroüin as a seventeenth-century French speaker might have done, we get something like Irwin, Irvine, or Irvin as the family name.

The obituary offers a further clue to the family’s identity. It says, “one of her sisters had married Monsieur the Marquis de Bâgny, an Italian.” This clue leads to a letter, now in the Scottish Catholic Archives at the University of Aberdeen, that was sent in 1668 from Paris to “Madame la Marquise de Bagni.” Its author was the marquise’s brother — and presumably therefore also the brother of Marie Hiroüin — John Iroüin of Hilton. Another document in the same archive from 1662 names the Marquise of Bagni as Elisabetta Irouin, a noble Scottish woman and daughter of Alessandro Irouin from Aberdeen. This, therefore, was Marie Hiroüin’s family: the Irvine (also spelled Irvin) family of Hilton, near Aberdeen, Scotland. Marie’s own Scottishness is more complex.

The records of the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec describe Marie Hiroüin as “écossoise.” In a basic sense, this did mean Scottish, as dictionaries of the time explain. Yet the nuns in Quebec wrote that she came from France. Hiroüin was part of a large early modern Scottish diaspora. Between sixty and eighty thousand people left Scotland for continental Europe in the first half of the seventeenth century alone, and many of these migrants had children while abroad. Their identities could combine elements of different national origins. People in Europe were described as Scottish even when their families had not lived in Scotland for several generations. In France they were eligible for naturalization. Hiroüin, therefore, certainly could have held identities associated with both Scotland and France while living in Canada.

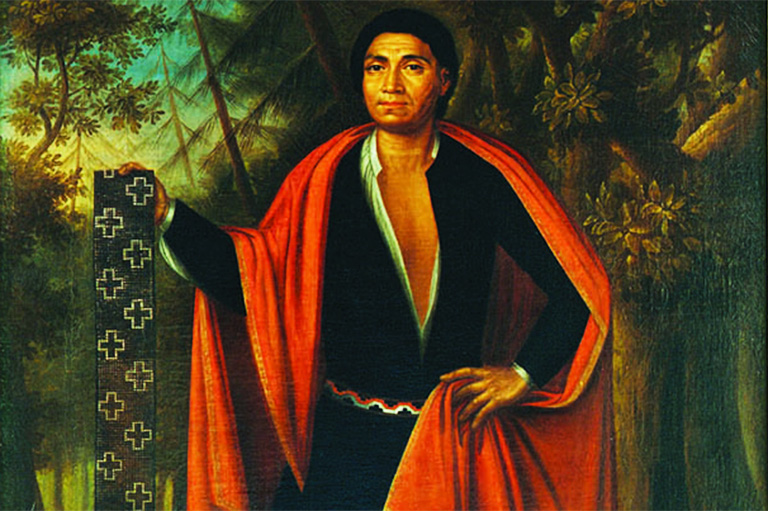

Another phrase in Hiroüin’s obituary provides an additional connection between her family and Scotland, with a curious geopolitical detail. It says she was from “one of the first houses of Scotland, allied to Marie Stuart, queen of England.” Readers today may know Mary Stuart as Mary, Queen of Scots, but they would almost certainly not think of her as a queen of England. The reference to Mary Stuart as an English monarch might appear to cast some doubt on the scribe’s understanding of British geography or history. It was probably not an accidental slip, however, but rather a political commentary.

Advertisement

To understand the significance of calling Mary Stuart an English queen, we need to move from New France to Tudor England, and think about Britain’s political situation in the midst of a religious reformation. Elizabeth Tudor ascended the English throne as Elizabeth I in 1558. She is now among the most famous of monarchs, and many celebrate her reign as an Elizabethan golden age. But not everyone in Elizabeth’s own time accepted her claim to queenship. Roman Catholic law did not recognize her father Henry VIII’s divorce from his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, nor Henry’s subsequent marriage to Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn. According to this interpretation, Elizabeth’s parents were never married, and Elizabeth was therefore not a legitimate heir to her father’s throne.

Some who opposed Elizabeth as queen favoured instead her cousin Mary Stuart. The French king at the time of Elizabeth’s accession, Henri II, refused to acknowledge Elizabeth’s legitimacy and claimed instead for Mary the title and arms of England. Adam Blackness, a Scottish Catholic who lived mostly in France, wrote that Mary was the “natural and legitimate Queen of Scotland and England,” and the “true and legitimate queen of all Great Britain,” in contrast to Elizabeth Tudor, “the usurper of the kingdom of England.” According to Blackness, everyone even a bit versed in the affairs of England knew Elizabeth to be illegitimate.

Whatever their views on the Tudor succession, many Europeans were shocked when Elizabeth had her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots executed in 1587. Some of the outrage among Catholics derived from a sense of religious solidarity with an executed Catholic, but the French felt a national attachment, too. Mary Stuart was a French figure. She was the daughter of the French noblewoman Marie de Guise; she had grown up mostly in France; she was French-speaking; and she had been the French queen while married to King François II, until his death in 1560.

The French attachment to the Queen of Scots endured beyond her death. In a funeral sermon that King Henri III of France ordered to be delivered at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the Archbishop of Bourges cried that Mary Stuart was “accused of being a Catholic! O happy crime! O desirable accusation!” An early seventeenth-century French account of Mary’s life portrayed her giving a speech in her antechamber on the way to her execution, proclaiming, “I die a faithful Scottish woman, faithful French woman, and faithful Catholic.”

In saying that Marie Hiroüin was from a family allied to Mary Stuart, Queen of England, the annalist at the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec was staking a position from afar in a longstanding debate about the Tudor succession and who had the truest claim to the English throne. It is difficult, though, to decide how seriously to take the implied connection between a nun in Quebec and the Queen of Scots. Scottish people in France were known to emphasize or even fabricate lineages by claiming to be descended from nobles who had arrived in earlier generations, and there were so many who claimed royal family connections that the French had a saying: “Not all Stuarts are cousins to the king of Scotland.”

The claim of an alliance to Mary Stuart did, at least, impart some celebrity sparkle to the Hôtel-Dieu community. Probably more deliberately, it served to highlight the significance of humility in someone the nuns writing the obituary said was “always offering herself for the most arduous and the lowest tasks.” Such humility was all the more impressive if the nun was from a noble lineage; and, according to the obituary, “what infinitely revealed the nobility of her family, is that her kin only left their country to conserve their religion, which is an illustrious proof of their great piety.”

In this statement, the nuns at the Hôtel-Dieu were alluding to the religious reformation in Scotland, led by the austere and passionate Protestant minister, John Knox. In 1560, an act of the Scottish Parliament ratified a Protestant confession of faith and outlawed the authority of the Catholic Church. Scottish religious authorities shared with early modern European Christians in general an assumption that they had a divine duty to enforce the acceptance of correct doctrine. In establishing the new national church, the Church of Scotland, they took measures to convince or coerce strays.

In 1573, the Scottish Parliament passed an act declaring it to be “godly and expedient that all his hienes subjectis worschip the only trew God in the uniformitie of religioun” and ordering that the names of people suspected of being Catholic and of those who did not partake in reformed sacraments be recorded. This act also demanded that all Scots give a testimony of their Protestant faith, as set out in the Scots Confession, and submit themselves to the discipline of the “trew Kirk” or suffer excommunication.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In 1592, Parliament made the connection between Catholicism and treason into law, declaring that the saying of mass, as well as the sheltering of Jesuits and seminary priests, would be “just caus to infer the pane and cryme of tressoun.” An enactment by the Scottish Parliament in 1609 declared that Catholics, along with those who aided and abetted them, were liable to have their goods confiscated; those refusing to participate in Protestant communions were to be excommunicated and have their rents and revenues sequestrated; and those who stubbornly persisted in their defiance were to face charges of treason that could result in execution and forfeiture of estates.

In 1614, the Privy Council warned against “sindrie personis” who were opposed to the “trew religion,” and described recusants and non-communicants as the “most pernitious pestis in this commounweale.” Scottish declarations such as these were generally more severe in tone than in practice. But while the open practice of Catholicism still continued in some aristocratic houses, Catholicism was deinstitutionalized, and the national identity of the country became increasingly Protestant.

In the early decades of the seventeenth century, members of Hiroüin’s family were pursued by the Kirk Session (the Scottish church courts) for recusancy, or refusing to attend Protestant services. They were subsequently exiled from Scotland for their continued refusal to conform to the religion professed by law in the kingdom. They settled in Dieppe, joining waves of Catholic clergy and nobility who went to the continent as confessional exiles. A record from the Scots college in Rome, one of the institutions established in continental Europe for the education of Scottish Catholic men and boys, indicates that the brother who wrote the letter in 1668 to the Marquise of Bagni was a student there. It states that in 1659 John Irvin of Hilton came to the college, studied philosophy and theology, and was made a priest. He also swore a mission oath, promising not to enter a religious order until he had served as a priest for at least three years in Scotland. He then worked for several years as a missionary in Scotland, supporting the Catholics who remained in the country.

While Scotland’s national identity was becoming increasingly Protestant, Catholicism was growing more important to the colonial identity of New France. The exclusion of non-Catholic colonists began in 1627 with the foundation of the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France, whose charter called for the peopling of the colony with French Catholics. By French law, Indigenous people who professed Catholicism would be counted as French. Because the Crown understood that these Catholic converts would help the French colony survive, religious conversion of Indigenous people was not politically neutral. It extended French sovereignty in North America, which made missionaries indispensable to the French colonial effort.

Hiroüin was one of those missionaries. According to her obituary, her purpose when she first set sail in 1643 was to become a nun in Canada; however, after she arrived in Sillery, “the temptation to return proved so strong that she surrendered.” She was certainly not the only one who changed her mind about settling. The French settler population in Canada at the time was very small, numbering only about 250 for all of New France. Many, possibly even most, migrants from France to New France did not stay, but instead returned to Europe.

Material conditions in the hospital at Sillery were basic. An almost tactile illustration is provided by a special dispensation the nuns obtained for their clothing. Members of their order usually wore white, but they found that the smoke, grease, and dirt in their hospital meant that their habits could not be kept that colour. The Jesuits counselled them to wear black or grey instead. The nuns were at first reluctant. But then, noting that their clothing was always dirty no matter what care they took, and becoming very fatigued by the laundry, they resolved to put on grey robes.

Advertisement

The state of their clothing was not their only challenge. The nuns reported that they were close to starvation several times (they were saved by gifts from Indigenous neighbours), and, like most French settlers, they found the long, cold winters very difficult. It is perhaps no wonder that a teenager from Dieppe decided not to stay. It is interesting, though, to think of why she decided to return.

A hospital served multiple functions for early modern Europeans. It cared for the sick, provided relief for the poor, and offered a visible outlet for charitable donations by the wealthy. The Hôtel-Dieu in New France followed in that tradition, but its overarching goal in its early years was the conversion of Indigenous people. From the perspective of the hospital’s founders, this goal was an extension of what hospitals were trying to do in France, which was to correct Christians who were in the wrong sect (for French Catholics, this meant Protestants) and to teach the proper observance of religion to those who were ignorant (for the elite, this meant the poor). A seventeenth-century French handbook for parish priests explained bodily care as a conversion strategy by saying, “it is certain that by the cure of the body one can as often cure souls as with sermons and good advice.”

The hospital at Sillery was not only supposed to provide medical assistance to those who needed it but also to draw people to Catholicism. As the royal letters establishing the Hôtel-Dieu stated, the hospital was one of the “means of attracting the [Indigenous] peoples and the infidels of New France to the true religion.”

The missionaries did not succeed as fully as they had hoped or expected. Although the colonial authorities presumed that the Jesuits were in charge of the mission, the Indigenous inhabitants asserted a considerable amount of independence. The location of Sillery, for example, on a point of land extending into the St. Lawrence River, was chosen because it was an excellent place for eel fishing and had been so for Indigenous people, as the Jesuits put it, since “time immemorial.” It was not the French missionaries’ first choice of site, but they deferred to Indigenous preference. Missionaries soon learned that the Indigenous residents at Sillery would continue to practice their traditional forms of leadership, housing construction, and food harvesting and preparation — and that they would retain their objections to French methods of corporal punishment.

The hospital remained at Sillery only until 1644, when fears about vulnerability to attacks by the Iroquois led the French to relocate it to a position within fortified walls. When Marie Hiroüin returned to Canada in 1657, the Hôtel-Dieu had been moved to where it still stands today, in the Upper Town of Quebec.

With French settlers forming the majority of patients in a substantial new building, the working environment would have been more familiar to a nurse from France than what Hiroüin had encountered when she first arrived in 1643. The nuns as nurses were at the centre of health care provision. They built their hands-on skills through working together at the Hôtel-Dieu, while also developing theoretical knowledge through information networks that kept them informed about current medical thinking abroad. They were expected to uphold cleanliness and neatness in all things as both a physical and a spiritual discipline, and this emphasis on purity helped to improve the hygienic state of the hospital, which, in turn, likely contributed to a reduction in mortality among patients.

Hiroüin’s role was an important one, and she was well regarded for providing an essential service. French hospital nuns were expected to be simultaneously gentle and authoritarian, obedient and courageous, humble and competent, while showing heroic compassion towards the suffering sick. Hiroüin would have seen many changes during her time in Canada, yet constancy was expected in her vocation.

Hiroüin was also constant on a more personal level. Throughout her time at the Hôtel-Dieu, she maintained a close friendship with Catherine le Contre de Sainte Agnès, the nun who had travelled with her from France. Both served in the hospital with what the annalist called “a great faithfulness,” with God himself as the link in their union. When le Contre was dying, Hiroüin asked that her friend call on her to follow. On the day of le Contre’s burial, Hiroüin fell sick and reported in good humour to her sisters that she had not expected le Contre to call her quite so soon, remarking that “she is in that other world as busy as she has been in this one.”

It seems fitting that Hiroüin would note such busyness approvingly. She had spent half her life at the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec, where the tasks of health care never ended. Her care was directed to those right before her, but her fellow nuns knew that her place could be understood in a much larger context, too, as part of a Scottish diaspora, a link to royalty and reformation, and an agent of French colonization.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement