Pride and Prejudices

On April 12, 1792, Hannah Jarvis boarded a ship in London, England, for a two-month-long journey across the Atlantic Ocean. Born in 1763 in Hebron, Connecticut, she was the daughter of a Loyalist who had fled to England before the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775. While escaping America ahead of a tar-and-feathering mob, her father, Samuel Peters, had instructed Cesar and Lowis — the married couple whom he kept in slavery — to care for his house and property until he returned. But Hannah Jarvis was not returning to Connecticut. Instead, she was headed to the new British province of Upper Canada, where her husband, William Jarvis, had been appointed secretary and registrar.

The night they sailed, Hannah Jarvis began the first of a long series of letters to her father in London, which would describe her impressions of her new home. She explained that her whole family — two daughters, one son, her husband, and herself — were “enclosed in the same room,” while their governess had a roomy stateroom, and their two servants were on a lower deck. Her letter, sent back with the captain of the pilot boat, ended with the words: “Preparing for setting full sail — Adieu.”

The principal chronicler of life in Upper Canada has always been considered by historians to be Elizabeth Simcoe, the wife of the province’s first Lieutenant-Governor, John Graves Simcoe. However, Elizabeth Simcoe lived in Canada for only five years before returning to England, while Hannah Peters Jarvis arrived in 1792 and remained there until her death in 1845. Hannah Jarvis’s gossipy and often withering letters and diaries reveal the social dynamics and class conflicts in pre-Confederation Upper Canada, as she struggled to maintain her family’s position among the province’s upper crust.

After a tempestuous journey across the Atlantic, Jarvis’s ship at last arrived in Montreal. Her son, Samuel (named after his grandfather), “ran off into the meadows instantly and had 20 tumbles in the grass which was nearly up to his chin.”

A short stay in Montreal was followed by a trip to Kingston, where the Jarvises learned that Simcoe had decided on a town, formerly known as Niagara but which he renamed Newark, as the temporary capital of Upper Canada. William Jarvis proceeded ahead of the rest of the family in order to, as he said in a letter to his father-in-law, “find a spot to place my wife and lambs.”

The town of Niagara had been established ten years previously. At the end of the American Revolution, Loyalists from New England, Pennsylvania, and New York State had fled to Fort Niagara, located on the eastern side of the Niagara River at the spot where it flows into Lake Ontario. The fort was occupied by the British military, as were forts Detroit and Michilimackinac, and would not be turned over to American control until 1796 following the signing of a diplomatic agreement known as Jay’s Treaty. With overcrowding and dwindling supplies in Fort Niagara, members of the newly disbanded Butler’s Rangers Loyalist regiment began to move across the Niagara River and to occupy the fertile land on its western side — land that is now part of the province of Ontario.

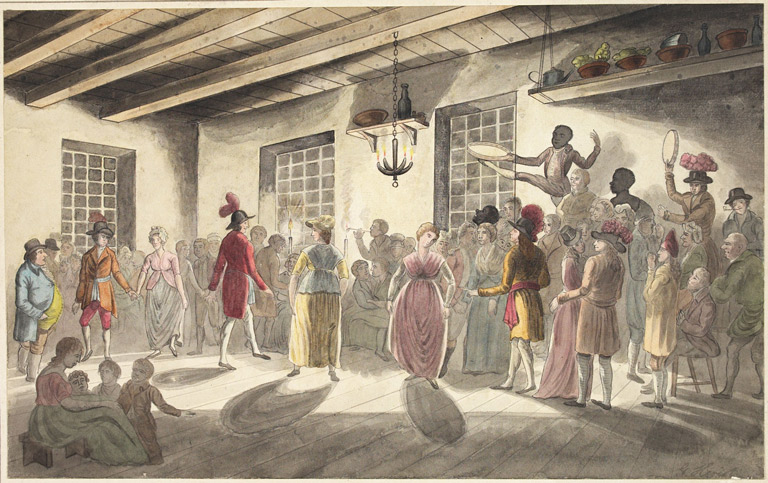

When Simcoe and his entourage arrived in Niagara by boat, they found military buildings along the edge of the river, while merchants — mainly Scottish — and tradespeople had built their stores and houses slightly inland from the riverbank. The Anglicans were holding services in the Freemasons’ Hall under the guidance of Robert Addison, a missionary for the Society of the Propagation of the Gospel who had known Hannah Jarvis’s father, himself an ordained Church of England minister, in London. The Presbyterians were raising funds to build a wooden church, which was completed in 1795. Newark, in 1792, was described by an anonymous letter writer as “a poor wretched straggling village with a few scattered cottages erected here and there as chance, convenience, and caprice dictated” and by William Jarvis as “a spot on the globe that appears ... as if it had been deserted in consequence of a plague.” After a long search, he finally bought a log cabin to house his family.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Like his wife, William Jarvis was a Connecticut-born Loyalist. When the American Revolution broke out, he enlisted in the Queen’s American Rangers, a regiment under the command of Major John Graves Simcoe. In June 1781, William Jarvis was severely wounded at the Battle of Spencer’s Ordinary in Virginia. After being injured again in an anti-Loyalist attack in his hometown after the revolution’s end, he moved to London, England, where he met Hannah Peters. They were married in 1785 and moved in with Hannah’s father. In 1792, William Jarvis was approached by his former commandant, who invited him to become the secretary and registrar of the newly created province of Upper Canada. William Jarvis had no particular qualifications for this position, which involved drawing up and registering land grants. Simcoe, apparently, offered him the post because he felt sorry for the man who had been wounded while under his command.

Britain’s Constitutional Act of 1791 set up the governmental structure of Upper Canada. The executive branch consisted of the Lieutenant-Governor, the executive council, which he appointed, and the officers of the Crown, which included positions such as the inspector general, the Attorney General, and the receiver general. The legislative branch was composed of a legislative council, appointed for life and therefore similar to the English House of Lords, and an elected assembly whose decisions could be vetoed by the Lieutenant-Governor as well as by the legislative and executive councils.

William Jarvis’s administrative position as an officer of the Crown placed his family in the upper class of Upper Canadian society. But conflict existed even among this small group. The Jarvises found themselves on a lower rung because they had been born in the American colonies, not in Britain, the birthplace of nearly all the other members of the administration. In 1796, Hannah Jarvis told her father that Simcoe “has set his face against all Americans. Russell and White [two officers of the Crown] think an American knows not how to speak.”

Elizabeth Simcoe mentioned Hannah Jarvis in her diaries only once, in a passing reference. Jarvis, on the other hand, frequently criticized Simcoe in letters to her father, at times asking him not to reveal her opinions to others. In one letter she referred to Simcoe as “the little stuttering Vixon.” Jarvis’s animosity seems to have been motivated by a combination of jealousy of Simcoe’s wealth and of her freedom to travel about sketching the countryside, along with disapproval of Simcoe’s influence over her husband, the Lieutenant-Governor. When Simcoe failed to attend an important ball in Newark for a second time, Jarvis concluded that she was feigning illness.

Advertisement

While still in Kingston, Jarvis began to complain about the two servants who had accompanied them from London. Fanny “has left me and gone to the dogs. Crossed the lake with one of the sergeants of the Rangers, and prevailed on him to marry her,” Jarvis wrote. “We cannot get a woman who can cook a joint. A soldier’s wife is all we can get. I have a Scotch girl from the Highlands. Nasty, Sulky, Ill-tempered creature.” Their other servant from London, Richard, whom Jarvis described as “a perfect sot and insolent,” left them about a year after Fanny, and “not without giving us every ill word that man could do.... This is one of the worst places for servants that can be. They are not to be had on any terms.”

Eventually, Charlotte Adlam, the governess who had sailed with the family, left their employ to marry a well-connected local merchant named William Dickson. “I think it will be a very good match for her,” Jarvis wrote to her father. Indeed it was: Related to Judge Robert Hamilton, one of the wealthiest men in the province, Dickson went on to become a successful businessman, lawyer, and justice of the peace as well as the owner of the first brick house built in Upper Canada. He later developed his 1,600 hectares of land along the Grand River into the city of Galt (now a part of Cambridge, Ontario).

In Upper Canadian society, having servants not only gave social status to those who were able to afford them but was also extremely helpful in maintaining a household without today’s modern conveniences. Not only did Jarvis have to ensure that the routine housekeeping tasks such as cooking, cleaning, washing, and sewing were accomplished, there were other demands on her time in the small town of Newark. She spent time caring for women who were ill or in childbirth. And, with no schools yet established, once the governess left, Jarvis spent a considerable part of her day teaching her children to read and write, a task about which she complained to her father. In addition, Jarvis was expected to entertain guests and to attend social events in town. According to Jane Errington, a professor at Queen’s University who has extensively studied the social history of Upper Canada, servants were considered crucial to people of Jarvis’s social standing and position as a wife of a member of the Upper Canadian administration.

However, the greater opportunities for social mobility in Upper Canada, compared to Britain, made it hard for people such as Jarvis to retain servants. With many more men than women in the province, female servants frequently married soldiers or farmers, feeling that marriage gave them more security. Male servants took advantage of their eligibility to apply for free grants of land, which, when settled and farmed, were likely to give them much higher incomes than the meagre wages they received in domestic employment. As well, because of the high demand in Upper Canada, a servant who was at all competent could easily be induced to move to another position with the offer of higher wages.

After her frustrating experiences with servants, Jarvis wrote to her father in the summer of 1792, asking him to send her the enslaved family who, she assumed, still lived in the house where she’d grown up in Connecticut: “Would you have any objection to Cesar and family come to us? They will be all Free when they come to this Province. We shall give them wages, those that we employ. The rest can take up their land and work for themselves.”

Undoubtedly, Jarvis had not learned that Cesar and his family were, by this point, already free. Thirteen years after he had fled to England, Samuel Peters had authorized his brother to turn over Cesar and Lowis and their eight children to a slave dealer in order to pay the property taxes that Peters owed to the town of Hebron. By the time word of their capture spread through Hebron, the family had been forcibly taken to a ship, on which their captors intended to transport them to South Carolina. The townspeople, who considered Cesar and his family well-respected members of the community, rode to the ship’s dock and rescued them. Two years later, a petition for the emancipation of Cesar and Lowis Peters was granted by the state legislature. This has been called one of the first incidents of abolitionist action in the United States, and Hebron is now a stop on the Connecticut Freedom Trail.

Hannah Jarvis’s intention in promising Cesar and his family their freedom is not explained in her letter. It may have been an attempt to entice them to leave the town where they had lived all their lives. Possibly the Jarvises couldn’t afford to feed, clothe, and house an entire enslaved family. In any case, it wasn’t due to any doubts on her part about the morality of slavery; Jarvis supported and benefitted from the institution.

Nor were the Jarvises the only residents of Newark who held people in slavery. Peter Russell, the province’s Auditor General and a member of the legislative council, was a slave owner, as was Colonel John Butler, who had formed the Loyalist military unit called Butler’s Rangers during the American Revolution and who later became deputy superintendent of the Indian Department of Upper Canada. In fact, six of the nine members of the original legislative council owned enslaved persons; it was a common practice in upper-class households in Britain and the New England colonies in the eighteenth century.

However, abolitionist sentiment was on the rise in Upper Canada. On July 7, 1793, the legislative assembly passed the Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to Limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude. The result of a compromise between the evangelically religious abolitionist Simcoe and the many slaveholders of the legislative council, the act did not end the practice of slavery in the province; nor did it free a single person. What it did was to make the importing of enslaved people illegal, although their sale and purchase within the province was still allowed. And it decreed that children born to enslaved mothers after the date of the act would be free when they reached the age of twenty-five. It also stated that any foreign fugitives from slavery would become free when they arrived on Upper Canadian soil.

Hannah Jarvis, in a letter to her father two months after the act’s passage, commented: “Simcoe has by a piece of chicanery freed all the [slaves] by which he has rendered himself unpopular with those of his suite, particularly the Attorney-General [John White, another slave owner].” Jarvis, dramatically exaggerating the effect of the law, must have understood the act well enough to know that what she wrote was not true. Although Simcoe’s act caused slavery to dwindle until, by the 1820s, it had nearly disappeared, the practice was not completely abolished in Upper Canada until 1834, when it was outlawed in the British Empire.

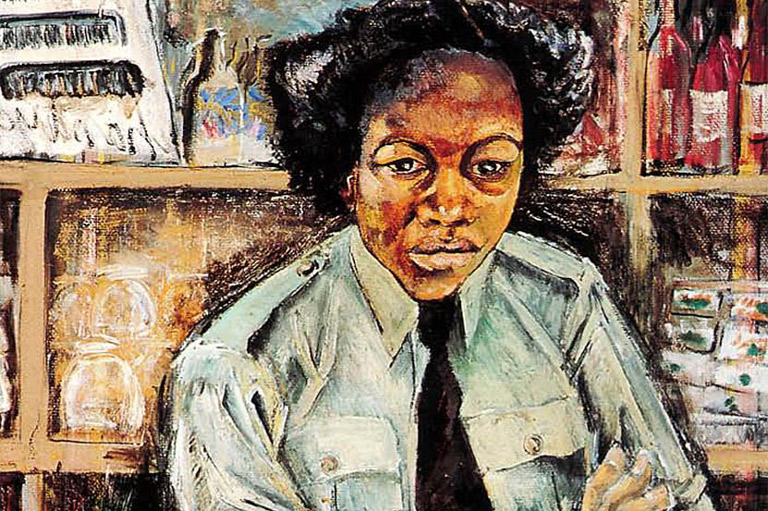

The Jarvises owned at least six enslaved men and women. Two of them, “Moses and Phoebe ... slaves of Mr. Secy. Jarvis,” were baptized at St. Mark’s Anglican Church in Newark in 1797. A few years later, Jarvis told her father that she owned two enslaved married couples: “the men are good, one of the women is tolerable and other, a devil, was brought up in the family of old Mrs. Harrison in Boston.”

One slave, Henry Lewis, ran away from the Jarvises and sought refuge in Schenectady, New York. In 1798, he wrote a letter to William Jarvis asking to be able to buy his own freedom and explaining that he had run away to “enjoy all the benefits which may result from my being free in a country whear a black man is defended by the laws as much as a white man is.” Lewis had some choice words about Hannah Jarvis: “The reason why I left your house is this, your woman vexed me to so high a degree that it was far beyond the power of man to support it.”

It may seem curious that an enslaved man from Upper Canada sought freedom in the United States just as American freedom seekers began seeking refuge in Canada. However, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 outlawed slavery in the U.S. Northwest Territory — which was later divided into the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin — and New York began the process of gradual emancipation the year after Henry Lewis arrived there.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

For the upper-class women of Upper Canada, retaining a household of servants or slaves was not the only marker of social status. The wealthy, including Elizabeth Simcoe and Elizabeth Russell, the sister of Auditor General Peter Russell, displayed their status by bringing with them from Britain great quantities of clothes made from fine fabrics and embellished with precious jewellery. An inventory of Elizabeth Russell’s jewellery took up three closely written pages. Jarvis told her father, “here is more profession of dress in an Assembly than I ever saw in London. We Londoners think that they must suffer greatly under the load of finery that stands piled upon them, for it literally stands; feathers, not an inch of them lost in fixing them in or on their caps.”

Not having the equivalent finery in her own wardrobe, Jarvis made a virtue out of a necessity and extolled her own modest dress when telling her father of a social call she had paid on the Servos family, who owned a grist mill in the area. “As soon as Mrs. Servos understood that I was an American [Loyalist] she sent me lard and sausages, pumpkins, Indian meal, squashes, potatoes, carrots, etc., etc.,” Jarvis wrote. “You cannot think how much it seems to please them when we ‘condescend,’ as they say, to go and see them. I soon found that their eyes were fixed on me as an American to know whether I was proud or not. Mrs. McCauley [the local doctor’s wife] and I have gained the character of being the plainest dressed women in Newark.”

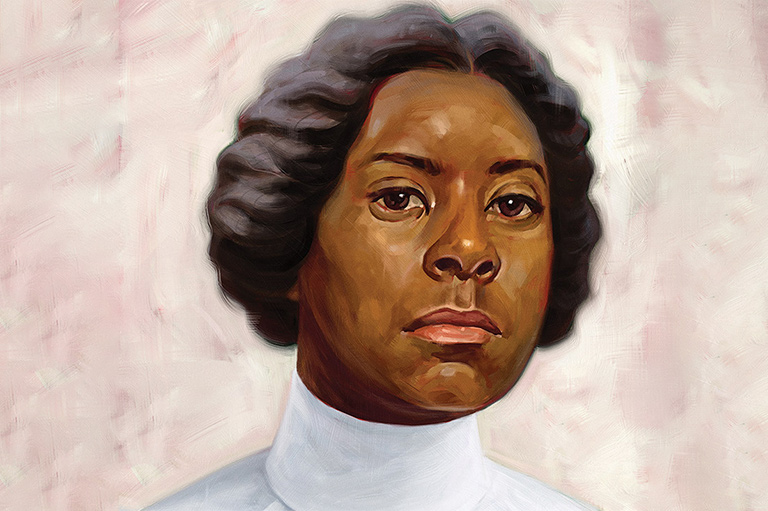

Perhaps Jarvis was plainly dressed compared to Elizabeth Simcoe, but she certainly wasn’t in comparison to the families that had come with Butler’s Rangers to the town. A portrait of Jarvis and her two daughters, painted by Robert Earl before they left London and now hanging in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, shows her wearing a gown of spotted muslin with a dark sash and sheer fichu, which she likely brought with her to Newark when she moved there. Cloth in Upper Canada was very expensive, and nearly all of it was imported. Those who were able to buy fabric would have paid the equivalent of $500 in today’s currency for enough cotton and coarse wool flannel to make an ordinary shirt and coat.

Although the Jarvis family belonged to the province’s upper class, severe illness spared no one in Upper Canada. Shortly after Jarvis’s arrival in Newark, her son, Samuel, was suddenly taken ill on October 10, 1792. He died nine days later at the age of five. Jarvis wrote to her father, “it has been a sickly season out here and a deadly one to children, so much so that there is scarcely a child left in the fort the other side of the river and numbers have died here.”

Advertisement

Jarvis had little time to grieve before she gave birth to a second son on November 15. William Jarvis wrote to her father that “both mother and child are unusually well.” The newborn son was named Samuel after both his recently deceased brother and his grandfather. Jarvis gave birth to another son and two more daughters over the next nine years.

Despite complaining in 1792 about how terrible the living conditions in Newark were, when the capital was moved to York (now Toronto) in 1796 the Jarvises didn’t want to leave. Hannah Jarvis blamed the move to York on her social rival, Elizabeth Simcoe. In a letter to her father, she wrote: “Everybody is sick of York. But no matter, the Lady likes the place and therefore, everyone else must.” When the Simcoes left Upper Canada later that year due to the Lieutenant-Governor’s ill health, Jarvis’s last words about them were: “John G. Simcoe has sailed to London with wife and two children where may it please his Majesty to keep him.”

William Jarvis finally followed the rest of the administration to York in 1798 and was granted one hundred acres (forty hectares) of land that lay between today’s Queen and Bloor streets. Meanwhile, the residents of Newark disowned the name that Simcoe had given to their town and went back to calling it Niagara. In 1798, the name of Niagara was officially restored to the town by an act of Parliament. (Nearly a century later, in 1970, the town was renamed Niagara-on-the-Lake.)

William Jarvis remained secretary and land registrar of Upper Canada, although he was frequently under attack for his incompetence, and the Jarvises piled up debt living a lifestyle they could not afford. Simcoe’s successor, Peter Hunter, discovering long delays in the issuing of land patents, repeatedly admonished William Jarvis, and threatened him with dismissal. William Dummer Powell, an Upper Canadian judge, called Jarvis “a distressed Man who has no duties to perform which call for Energy.”

William Jarvis’s income — a yearly salary supplemented by a fee for each land patent issued — was not nearly what he had anticipated. But this did not stop the Jarvises from living beyond their means. William Jarvis built what was called at the time “the largest home in York,” and the family was hounded by merchants to whom they owed large sums of money. In 1816, William made out a will, with Hannah’s consent, so that their eldest son, Samuel, would inherit all his property but also all his debts. On August 13, 1817, William Jarvis died.

Hannah Jarvis attended her husband’s funeral alone. Her son Samuel was in prison after having killed John Ridout, the son of Upper Canada’s surveyor general, in a duel. (He was acquitted of the murder charge the following month.) Her other children did not receive word of the funeral in time. Jarvis remained in her house in York for two more years and then spent the rest of her life moving among the homes of her four married daughters. Two of her daughters, Maria and Hannah, had married sons of Robert Hamilton, the wealthy merchant, landowner, and government official in Queenston, near Niagara Falls. Her daughter Ann had married the brother of John Beverley Robinson, who was the chief justice of Upper Canada for many years.

By 1830 Jarvis, although making occasional short visits to her other daughters, was permanently living with her daughter Hannah Hamilton and her husband, Alexander Hamilton, in Queenston. In 1839, Alexander died at the age of forty-eight, leaving his wife with nine children, a tenth on the way, a pile of debts, and a huge house with its attendant maintenance costs and property taxes. A few years before his death, Alexander had embarked on the costly construction of the house — a three-storey, porticoed Greek Revival mansion, which today is home to the Willowbank School of Restoration Arts.

The only income available to the family was Jarvis’s United Empire Loyalist pension from the government. But the twenty-five pounds sterling that Jarvis received on a quarterly basis did not go far. In one letter, Jarvis declared: “not a shilling in the house nor butter nor meat or potatos.” Her son, Samuel Jarvis — who had been appointed superintendent of the Indian Affairs Department, headquartered in Kingston — suggested that his mother, his sister, and her children move to Kingston. But Jarvis replied, “I agree with you that keeping this establishment is rather ruinous — still they are so comfortable where they are, and house rent is so high in Kingston.”

Rev. Thomas Creen, the rector of St. Mark’s Anglican Church in Niagara, wrote to Hannah Hamilton, “it has occurred to me, in thinking anxiously of your circumstances, that it would be one of the most ready and sure means of support to get together 15 or 20 girls and to establish a select school in your own schoolhouse.” He estimated that this “would ensure an income of 50 or 60 pounds per annum or perhaps more.”

But the two Hannahs decided on the solution of sewing for a living, and there are frequent mentions of it in Hannah Jarvis’s letters and diaries. For instance, on July 1, 1842: “finished 11 shirts, got 14 more.” Jarvis even suggested to her son that his wife should send her sewing over to Queenston from Kingston by boat across Lake Ontario. In one letter she told him, “your sister has gone to Niagara to seek needlework to put bread into the mouths of her children — if she does not succeed, I see but one way — that she and the children turn out as mendicants from door to door.”

Jarvis’s daily diary entries in those years in Queenston after the death of her son-in-law spoke of a constant routine of washing, cleaning, cooking, sewing, and care of the vegetable garden, orchards, and animals; and they included notations of all her expenditures. However — always feeling that she had to maintain her stature as a gentlewoman and the widow of a member of the Upper Canadian administration — Jarvis also wrote of inviting her wealthy neighbours to take tea with her in her daughter’s impressive home.

On August 29, 1845, Jarvis, who referred to herself in her diaries as H.J., wrote, “26 Weeks since H.J. was taken ill — getting worse every day — so weak she cannot stand alone — her thread is near spun.” She died on September 20, 1845, from a stomach tumour.

Jarvis’s letters and diaries provide insights into the interactions among people of different social classes in Upper Canada. She was uniquely placed to understand the importance of social status, since she knew both wealth and poverty. Through her position as a slaveholder, she sought to maintain a system that enforced racial and class inequalities. But she was fighting against the tide: Emancipation came in her lifetime, and social conditions offered upward mobility to her servants. Ultimately her letters tell a tale of a proud gentlewoman let down by a feckless husband, whose privileged position crumbled as the world around her changed but who fought tenaciously to maintain her family’s position in society.

FAMILY TIES

In the late eighteenth century, while Hannah Jarvis was living in Newark, meetings between British colonial leaders and Indigenous chiefs were held on the military reserve located one kilometre away from the Jarvis home.

A January 1793 letter from Jarvis to her father told of the “Council of the Six Nations held here for a week past. This morning they met to determine about some lands they wanted, [Mohawk Chief] Joseph Brant at their head; but the governor and they could not agree.... Captain Brant dined with us on the 13th, the first time I ever spoke to him.”

A few years after the encounter with Brant, the Jarvises became acquainted with members of another First Nation, the Mississaugas. In January 1795, Jarvis sent her father two portraits of her two-year-old son, Samuel, “in Indian dress and fur cap, or chapeau, Indian leggings and moccasins.” She added that her son had been given the name “Nek-Keek” and was “by adoption a Mississauga.”

According to Heather George, a curator of Indigenous histories at the Canadian Museum of History, it was common practice for Indigenous nations to adopt non-Indigenous people. Usually, the adoptee was a person from a family of influence who might have some role in supporting the needs of the First Nation. William Jarvis, in his job as land grant registrar, is likely to have attended the negotiations between the British and the Mississaugas at the Council House in Niagara and may have brought his only son along. — Elizabeth Masson

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement