Maritime Massacre

“Do you think there is any hope for us?” were the last words spoken by Matron Margaret Marjory (Pearl) Fraser to Sgt. Arthur Knight, who had tried to shepherd Lifeboat No. 5 to safety.

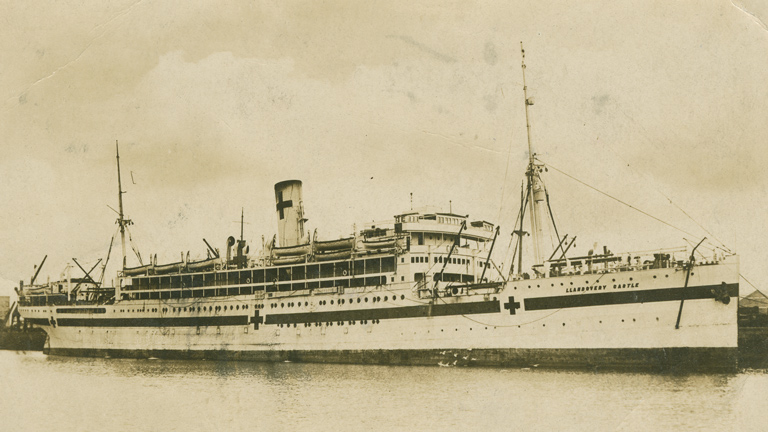

“No,” he admitted, before the whirlpool created by the sinking hospital ship HMHS Llandovery Castle capsized their lifeboat, drowning her, 13 other nursing sisters and eight crew members. Ten minutes earlier, on June 27, 1918, Germany’s U-86 had torpedoed the ship off the coast of Ireland.

The loss of the Llandovery Castle was the worst Canadian maritime disaster of the Great War, claiming the lives of 234 crew, medical officers and other ranks and nursing sisters. Knight, one of only 24 survivors, heaped praise on the nurses, noting he never heard a complaint or cry for help as they faced certain death. Identifying with the soldiers they cared for, these practical, hardworking professionals and proud officers have been dubbed “Sister Soldiers” by historian Cynthia Toman in her book Sister Soldiers of the Great War.

Pearl Fraser was one of some 61 nursing sister casualties of the First World War. Including the Llandovery Castle victims, 21 died as a direct result of enemy attacks; another third from pneumonia or influenza, mostly caused by the devastating 1918 Influenza Pandemic; and the rest from other illnesses. Matron Fraser, in charge of the Llandovery Castle nurses, exemplifies the experiences not only of the Canadian nursing sisters who died but also of all 2,845 who served overseas and in Canada. Most nursing sisters were well educated, having graduated from a three-year nursing program, and older than many of the men they cared for. Toman notes that some had also attended university.

Fraser graduated from the Lady Stanley Institute for Trained Nurses in Ottawa in 1908, but little else is known of her early career. The Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) regulations required each nursing sister to be a graduate nurse, unmarried, of high moral character and between the ages of 21 and 38 at enlistment. Fraser came from a prominent family; her father was Duncan Cameron Fraser, Nova Scotia’s lieutenant- governor from 1906 until his untimely death in 1910. Shortly after war was declared, Pearl enlisted, as did her younger brother Alistair and their cousins, fellow nursing sister Harriet and Wendell Steward Graham.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Like soldiers, nurses were motivated to enlist for reasons that included duty to country and financial security. But a sense of adventure was often evident. Fraser’s surviving wartime diary (1914-15) conveys her excitement as she travelled with the first contingent. She recorded the names of the ships in the convoy and called them “a glorious sight this moonlight [sic] night. Alastair [sic] on Ruthenia. Wendell on Zealand [sic]. Moosejaw [sic] boys on Royal Edward directly in front.” She also recalled the excitement caused when a sailor fell off the Royal Edward, noting, “someone had thrown several life buoys to him” and “the other ships closed in around us,” and “we felt he was comparatively safe [the] only fear being that he might become ‘exhausted’ from cold.” The half -hour it took to get him back on board was clear proof to Fraser that “his swimming saved his life.” She also reported on-board card games with fellow officers, an “excellent concert in 2nd cabin at night,” a church service and lectures.

After landing in England, Fraser went with the nursing sisters to St Thomas’ Hospital in London, where Florence Nightingale had founded the first modern school of nursing in 1860. Fraser shopped for clothes and supplies and took in the sights. Evenings were filled with plays and days with stops at the Criterion Restaurant, famous for suffragist teas and a reference in a Sherlock Holmes novel. Likely due to the distinctive Canadian nursing uniform that earned them the nickname “bluebirds,” Fraser observed that “people take great delight in looking at us. Our only way of getting them to stop is to look at their big feet until they are simply forced to lower their eyes.”

Like soldiers, nurses were motivated to enlist for reasons that included duty to country and financial security.

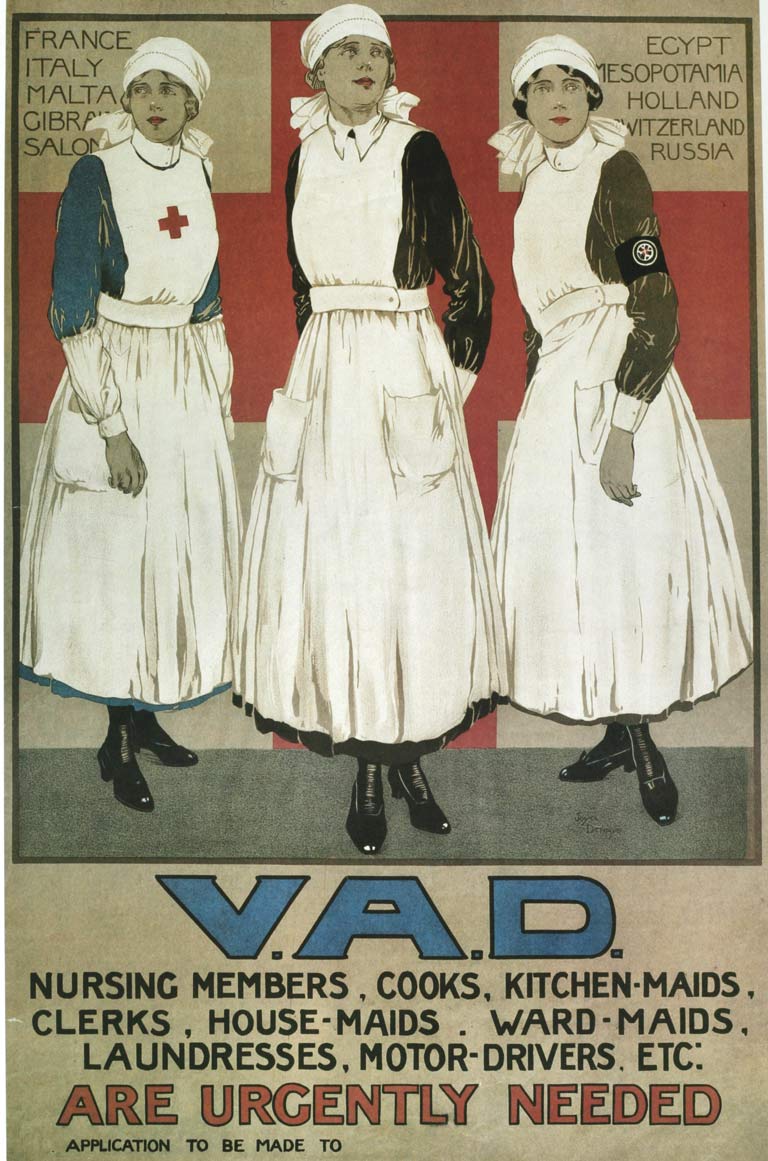

Nurses in the Great War

Nursing sisters were initially granted the relative rank of lieutenant. Although they could rise in rank with promotions — Matron-in-Chief Margaret Macdonald, for example, held the rank of major — women could serve only as nursing sisters, even if they were physicians. Rank afforded nurses some significant privileges, but it was relative, meaning that their authority was limited to the supervision of orderlies (ranked below them) and nurses in the unit and patients. This kept nurses firmly under military command, unlike their counterparts in the British and American forces, who served in auxiliary forces headed by nurse matrons.

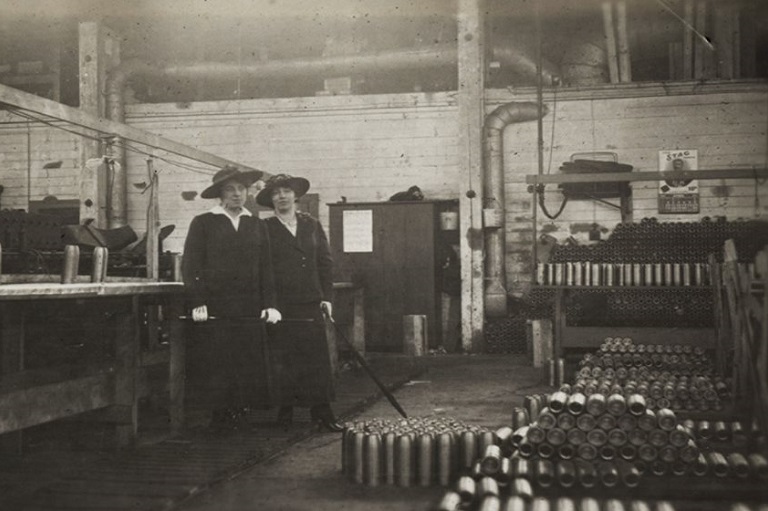

CAMC nurses played an integral role in ensuring that the Great War would be the first in modern history to have more Canadian soldiers die of enemy action than of disease. According to Desmond Morton’s book When Your Number’s Up, more than 90 per cent of Canadian soldiers who reached a casualty clearing station survived their injuries. CAMC nurses were skilled surgical assistants; kept vigilant watch over the patients’ changing condition; cleansed and bandaged wounds; administered medications; and fed and bathed soldiers. Nursing sisters did all this in the physically and emotionally challenging environment of warfare. They dealt with horrific injuries, many of which were relatively new and little understood: shrapnel that tore bodies to pieces, chlorine gas poisoning that damaged lungs, trench foot that could lead to amputation, tetanus, shell shock and the horrors of gas gangrene with its ominous odour. And, in an era that predated the golden age of antibiotic development, nurses fought a relentless battle against infection, using both older methods such as poultices and newly developed wound-irrigation techniques. It was a battle that saved many lives.

CAMC medical units were absorbed into the British system, which was organized along battle lines, with field ambulances accompanying the troops. Stretcher bearers carried wounded soldiers to regimental aid posts, where medical officers did assessments, administered morphine and bandaged wounds. Some patients were eventually sent to hospitals farther from the front, using an extensive network of ambulances, trains and ships.

The evolving military medical system grew as the war advanced. Fraser’s first major assignment as a nursing sister was to France, with No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital, which was established at the luxurious Hôtel du Golf, near Étaples-sur-Mer, with 300 beds. But as the battle settled into trench warfare and casualties mounted, this hospital was enlarged and moved to Outreau (near Boulogne-sur-Mer) in the fall of 1915. More CAMC hospitals, most organized by university medical schools, were added throughout 1915 and 1916. By 1918, the CAMC managed 16 general and 10 stationary hospitals (each typically having 1,000 beds or more), 72 nursing sisters, 30 medical officers and 205 other ranks. As well, they operated four casualty clearing stations. Canada also used five hospital ships, of which Llandovery Castle was one. These ships brought home discharged soldiers and those deemed “medically unfit” for further service. Nurses worked at many of these sites.

Advertisement

A Nurse’s Wartime Experience

The No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital’s first convoy of 115 patients arrived on Dec. 4, 1914, “suffering mostly from swollen feet [trench foot], frost bite, and minor gunshot wounds,” Fraser noted in her diary. In his book First World War Honour Roll of Guysborough County, Nova Scotia Vol. 1, historian Bruce F. MacDonald writes that in a letter published later in a Moose Jaw newspaper, Fraser described treating Canadians wounded in the Second Battle of Ypres who had experienced the devastating chlorine gas attack at St. Julien, Belgium, on April 24, 1915.

Even when the cases weren’t severe, the work could be exhausting. According to MacDonald’s book, Fraser noted: “Last night [April 26, 1915] we were asleep when at 1 a.m. an overflow of 300 arrived, not bad cases, but up we had to get, and it was pathetic. Most of them were nearly starved.… They were fed and dressed and places made for them to sleep over night before we again laid our own heads to rest.”

MacDonald notes that she also wrote, “We haven’t a minute to ourselves and our minds are so much on our work and our poor boys. We can neither think nor talk of anything else.” Sometimes, the work resembled an assembly line; for example, on a day when 300 or 400 wounded arrived, “Nursing is now out of the question; all we do is receive, dress, get them bathed, and fed, and then pass them on.” Every soldier who could be moved was sent via hospital ships to England.

Casualty clearing stations, some of them employing new blood-transfusion techniques developed during the war, provided surgical facilities near the front line and reduced the need to move patients long distances. They were found to improve survival rates. Fraser reported for duty at the No. 2 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station (No. 2 CCS) in February 1916. Still, there were misgivings about sending women close to the front. However, nursing sisters expressed a willingness to serve wherever they were needed, and a CCS assignment was considered a privilege, one that suggested a nurse was deemed competent to do difficult work under difficult conditions.

While hospital work could be exhausting, there were quiet periods between engagements when nurses had time to socialize and travel. Nurses helped organize Christmas parties and other events. Staff or convalescent patients or both usually provided entertainment for these — indeed, a sizable hospital could often put together a small orchestra or choir, or even stage a play. Friendships with other nursing sisters did much to sustain them through good times and bad.

“We haven’t a minute to ourselves and our minds are so much on our work and our poor boys. We can neither think nor talk of anything else.”

Fraser spent her first Christmas overseas with her brother and cousins in what local Nova Scotia historian James M. Cameron called “a circumvention of military security and red tape which was a unique accomplishment.” The two men were granted leave from their units in England, applied to the French Consulate for visas and travelled by ferry to Boulogne, where Fraser and her cousin Harriet met them in an ambulance. In December of 1915 and 1916, Fraser received leaves of absence of five days and two weeks, respectively.

Wartime nurses suffered emotional trauma from witnessing horrible injuries, knowing that some patients would never fully recover, experiencing the frustration of realizing they could offer little help, and comforting the dying. Many viewed soldiers with maternal or sisterly affection, and dismissed their own hardships in comparison with their “boys.” Nursing sisters wrote letters home for soldiers, sometimes informing a mother or wife of a deceased soldier’s last words; attended funerals; and placed flowers on the graves of those they lost.

Working conditions also took a toll. The unit diary of No. 2 CCS for Feb. 20, 1916, for example, noted “intense bombardment heard from the front all day long. Although 20 miles or more away our buildings shook and windows rattled.”

Even some of those serving in hospitals farther from the front often worked in tent wards or were housed in tents and huts; they offered minimal protection from the cold, rain and winds, which sometimes grew strong enough to blow down tents.

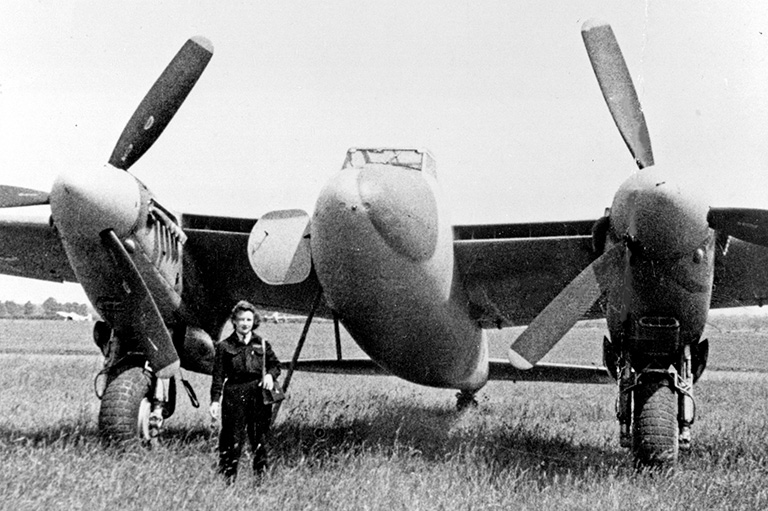

Many of the 14 nurses aboard Llandovery Castle had, like Fraser, served since the first few months of the war and were suffering from various health ailments themselves, including “neurasthenia” (exhaustion), a mental illness similar to PTSD. Overworked nurses were granted sick leave or assigned to hospital ships where the work was considered light. On the trip from England to Canada, nurses cared for convalescent patients, then returned with just CAMC members and crew.

In 1917, according to MacDonald’s book, after having served 2½ years on the continent, Fraser was reassigned to HMHS Letitia, then transferred that July to King’s Canadian Red Cross Hospital, Bushy Park, London, where she became nurse-in-charge. Then, in November 1917, Fraser was transferred back to hospital-ship duty, this time to HMHS Araguaya. On March 4, 1918, her youngest brother, Laurier, who had enlisted in 1916, was killed in action in France. Fraser left for a month’s sick leave in April 1918 with family in Nova Scotia.

She reported back for duty on May 17, 1918, having been appointed matron on Llandovery Castle — only to be killed a little over a month later. If Fraser continued her wartime diary beyond 1915, her family believes it was likely lost at sea, so we’ll never know her perspectives on the later years of her service.

Many nurses suffered from a mental illness similar to PTSD.

MacDonald believes that Fraser and her colleagues would want to be remembered as women who “selflessly responded to their country’s call to service in a time of need,” adding that they contributed “to the changes in women’s roles that occurred during the interwar years. While some eventually married and raised families after their discharge, others devoted their lives to nursing in a variety of capacities — public and military hospitals, public health and private nursing.”

Indeed, nursing, then still a relatively young profession, rose in status thanks to these women, as symbolized in Prime Minister Robert Borden’s extension of the right to vote to nursing sisters (along with the female relatives of servicemen) in 1917. While the move was also a political ploy to shore up support for his party and conscription, it nonetheless recognized nurses’ wartime service.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The Sinking of HMHS Llandovery Castle

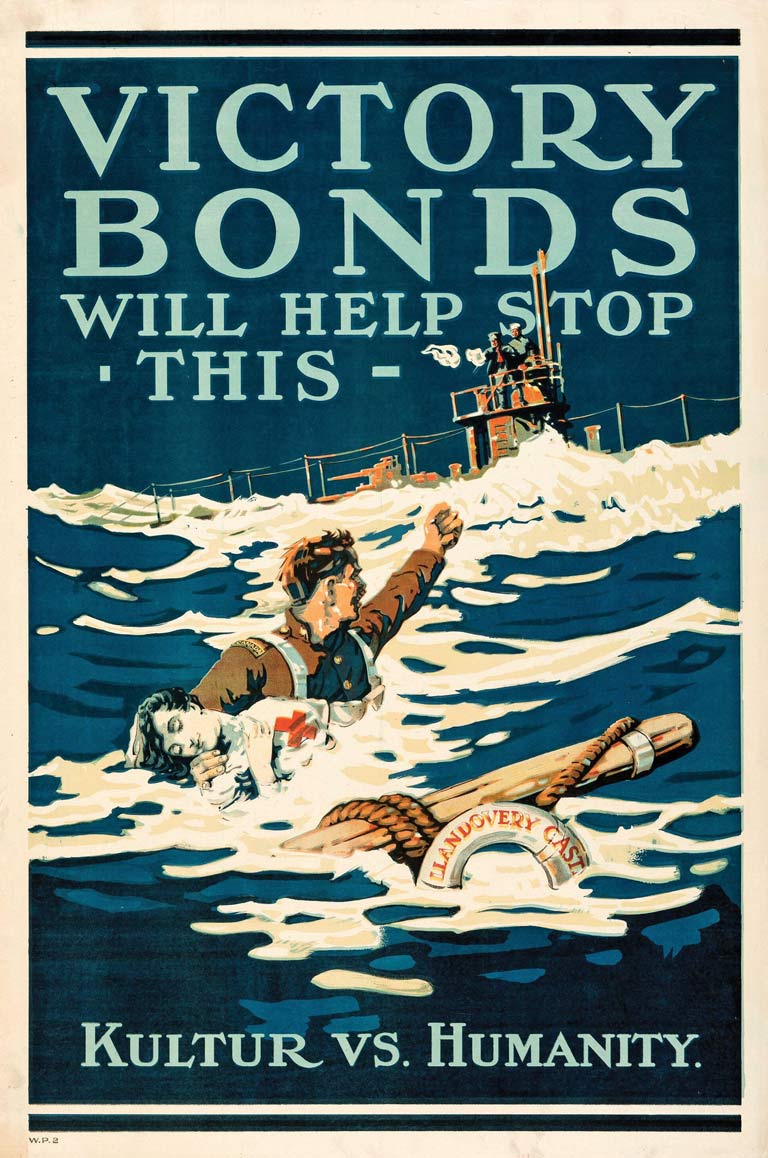

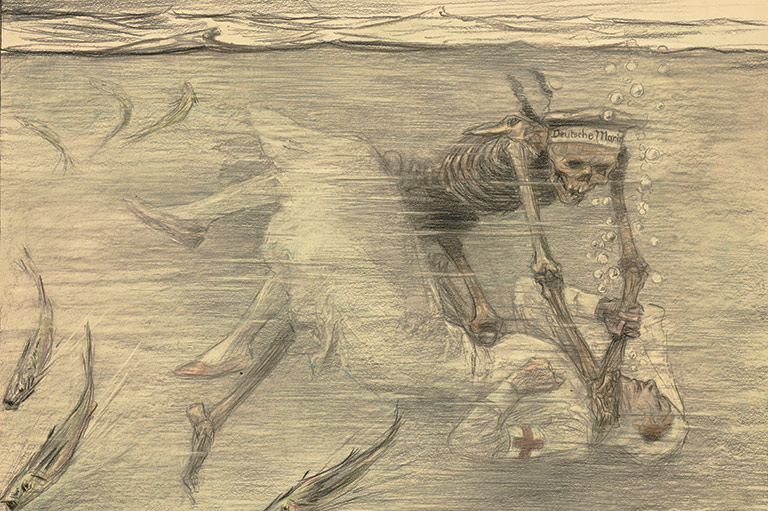

It is often said that truth is the first casualty of war. Admittedly, the German submarine U-86’s commander, Helmut Patzig, and his crew gave the Allied propaganda machine plenty of fodder when he managed to hit the hospital ship Llandovery Castle in its engine room, extinguishing all the lights immediately, preventing a distress call and sinking it within 10 minutes. Several lifeboats were launched and many of those that made it off the ship were rammed into and fired on, as if to destroy any evidence of their actions. Patzig accused survivors of carrying ammunition and harbouring American pilots.

Wartime posters focused most of their indignation on the 14 nurses. In a Victory Bonds poster, readers are told that buying the bonds would help stop this atrocity, showing a nurse lying helplessly in the arms of her male rescuer (see page 16). Interestingly, she is not wearing her bluebird uniform but one sporting a Red Cross, presumably meant to symbolize Allied outrage over the targeting of a well-lit hospital ship in contravention of the Hague Convention. The outrage was perhaps a bit disingenuous, given that this was certainly not the first German U-boat attack on a hospital ship — they occurred with increasing frequency by 1917.

The title of the American poster “Spurlos Versenkt” refers to an alleged German policy (literally, “sunk without a trace”). The poster shows women in a lifeboat under attack, although no nursing sister had died that way. One Canadian officer allegedly told his troops to use “Llandovery Castle” as a battle cry during the Battle of Amiens in August 1918, which launched “Canada’s Hundred Days,” a series of offensives that closed out the war with a victory that cost many lives.

We know little of what the nurses thought of these depictions. But nursing sisters knew the risks they took in boarding a hospital ship or, for that matter, working in a casualty clearing station, and accepted them as part of their duty as military officers.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement