Home-Front Green Gables

In 1924, at the age of forty, Myrtle Webb took up a pencil and began a diary she would maintain for the next thirty years: just a few simple sentences each day about the weather, family activities, community news, and the like. During the years of the Second World War, Webb’s diary captured a Canadian home front teeming with a revolving cast of servicemen and women. It is unique in that this home-front experience took place in what was well on its way to becoming the most famous home in Canada.

November 5, 1942

A lovely fine day and not very cold. Had two RCAF boys come in just as I had finished washing the dinner dishes. Gave them dinner. Almost finished another dress. War news better.

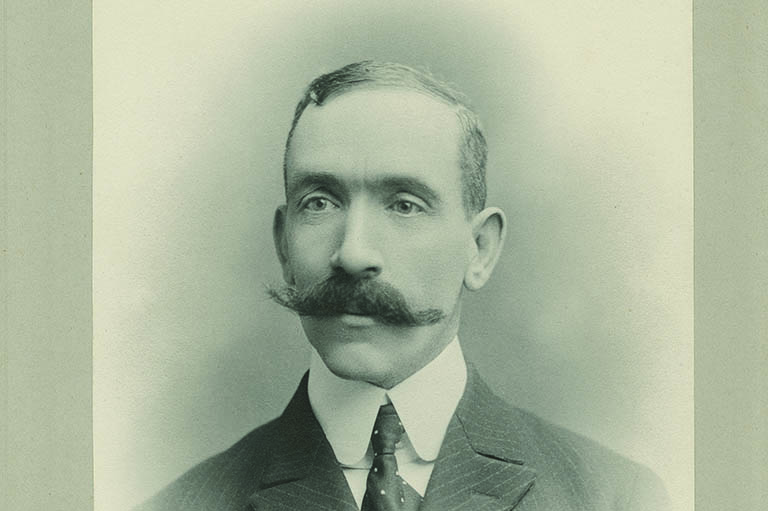

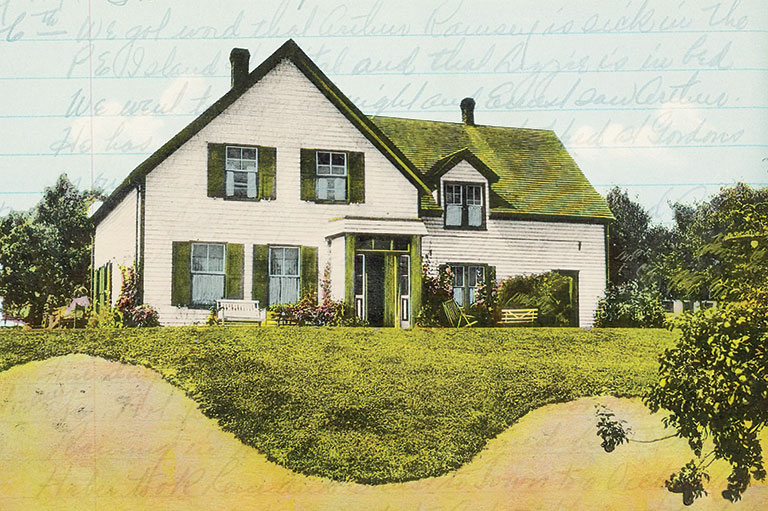

By the time Myrtle Webb jotted these words into her diary, the fifty-nine-year-old housewife was growing accustomed to off-duty airmen dropping in at all hours. They would come for tea and cookies, to chat with her and her husband, Ernest, to walk the old Webb farm, or even to wander through the farmhouse. The Webbs’ Cavendish, Prince Edward Island, home had become famous as an inspiration for the classic novel Anne of Green Gables, written by Myrtle’s cousin Lucy Maud Montgomery. Although their farm had become part of Prince Edward Island National Park in 1937, Myrtle, Ernest, and three of their children — Anita, Lorraine, and Pauline — still lived at Green Gables.

At the outset of the Second World War, Canada offered to take a principal role in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). Canada’s size, and the fact that it was within range of both Europe and Asia, yet too distant to be in danger of air attack, made it the perfect host for training military aircrews. BCATP schools were established across Canada, but Prince Edward Island was disproportionately favoured: The Minister of National Defence, J.L. Ralston, had recently been parachuted — figuratively — into a P.E.I. riding, and he ensured his constituents were well-treated. The province received training schools in Summerside and Wellington and an emergency landing strip in Wellington (not to mention a top-secret radar base in Tignish), in addition to its Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) base in Charlottetown.

As a result, there were as many as twelve thousand young airmen from Britain, Canada, and the rest of the Commonwealth on Prince Edward Island over the course of the war. When not in training, they had time to explore the province and came to appreciate a refuge where they might swim, golf, walk in nature, or just have a bite to eat. They found all this at Green Gables.

Myrtle and Ernest found something, too. After farming their property for decades, they had been convinced to sell, under threat of expropriation, to make way for the new park. The National Parks Branch, the precursor to Parks Canada, had allowed them to stay on — Ernest as park caretaker, Myrtle running a tea room — but life was not the same. Their house was not fully their home, and, in accordance with the park system’s focus on tourism and recreation in this era, the fields they had farmed were turned into a golf course. Hosting military personnel became the Webbs’ contribution to the war effort. And it gave their life purpose.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

September 3, 1939

Fine day, warm. Hitler determined to fight. So will England & France. Quite a number around but everyone very quiet and worried.

Myrtle Webb’s diary contains almost no reference to the run-up to war. Nor does she mention Canada’s own declaration of war on September 9, 1939. It is tempting to wonder if this was because the Webbs knew they were unlikely to be called to fight. Ernest was fifty-nine; Myrtle and their four daughters — Marion, thirty-two; Anita, twenty-seven; Lorraine, twenty-two; and Pauline, nineteen — would not, as women, be made to enlist; and their thirty-year-old son, Keith, ran his own farm and so would probably be granted an exemption.

But, like all Canadians, the Webbs were worried for their friends, family, and neighbours who might serve. (“War news nerve racking,” Anita Webb wrote in her own diary. “I have been thinking of all my boy friends.”) They worried about the war itself and about the possibility that Germany would be victorious.

Myrtle was quiet about the war because it was still so new and distant — and because she was otherwise so busy. Prince Edward Island National Park’s official opening had been that summer, and Green Gables had been flooded with visitors. Myrtle and her daughters ran the tea room, took green fees for the golf course, and generally welcomed literary pilgrims at all hours.

Myrtle seems to have recognized the strangeness of maintaining a normal existence during wartime. Later that September, she told her diary, “I made jam out of what I could salvage. Oh yes and there is war in Europe.”

May 28, 1940

Lorraine 23 today and she got her telegram from Ottawa to report as soon as possible. Another busy day. Pauline went to S. Side [Summerside] with Edward & Mary Willie & Reggie to see “Gone with the Wind.”

Life seemed, if anything, even more normal for the Webbs in 1940 than it had been the year before. The opening of the park, followed by the declaration of war, had the unexpected effect of making Green Gables more like their old home than it had been for years. Park-related construction was largely complete, so Parks Branch workmen were around less often. And, while the war did not eliminate tourism as one might have expected, it did batter the branch’s budget, meaning that any more development had to be deferred.

The war did intrude, however. The Webbs raptly listened to the radio about the German offensive in France and the Allied escape from the port town of Dunkirk. And Lorraine was called up to work in the civil service in Ottawa. She spent the war there as a code and cipher clerk in the naval service headquarters.

June 1, 1941

The worst tragedy Cavendish has known. Two Montreal RCAF boys and Harvard training plane crashed at the beach and burst into flames. I saw it from Old Orchard and we had a hard time getting central and S.Side. About all in at night.

War activity stepped up across Canada in 1941. Ernest collected donations for the Canadian War Services Campaign that provided goods for soldiers overseas, and the new Summerside Airport was opened as a training school; but it was this crash that brought the war home to Myrtle. It was a cool Sunday afternoon on Cavendish Beach, with a few bathers attempting to will the summer into existence. A small yellow prop plane out of Summerside, some thirty kilometres away, came in low over the water, circled several times, and smashed into a field behind the dunes. Dead were twenty-three-year-old Bonar Robertson and twenty-year-old Glen Fletcher of Mount Royal, Quebec. Myrtle phoned in the accident. The local Guardian newspaper expressed shock “that the quiet picturesque land of ‘Green Gables’ should have been the scene of Sunday’s grim tragedy.... Not even a quiet corner in rural Prince Edward Island can escape the stern realities of war.”

August 10, 1941

A terrible storm and Dads trousers are mostly in Ch.Town [Charlottetown]. 6 R Air Force here Don, Ken, Dick, Lem, Les, and Maurice and the Allens here in the evening.

Work was incessant for Myrtle that summer — and not only in keeping Ernest’s pants on the clothesline. Tourism numbers were up; Americans in particular, not yet in the war, found Canada a safe place to holiday. There was a new bus service dropping BCATP airmen off at the national park, fifty at a time. And to top it off, politicians had taken to asking Myrtle to host and feed dignitaries at Green Gables on short notice: Defence Minister Ralston one day, the South African representative to Canada the next. “The last straw. All in,” Myrtle wrote in exasperation after one such last-minute request.

More welcome was a group of men from Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF) who made Green Gables their second home while training on the island. It seems to have happened just by one or two getting to know the Webbs and then returning with friends. Myrtle chronicled their many appearances. “Ken Brookmen, Les, Lorne, and Maurice” stayed for a weekend. The Webbs were “guests of the Air Force” for dinner and a movie in Charlottetown. “Two new boys came out with Dickman-Wilkes, Dick Hovers and Gordon Hatherly.” The Webb girls made Maurice a birthday cake. Five RAF servicemen came one afternoon, played crokinole for hours, and had an evening cornboil. “They are nice boys.”

Myrtle began taking care in this period to note the names — often, full names — of military personnel she met, some-thing she did not do with ordinary visitors to Green Gables. She clearly wanted to hold a little tighter to their memory, in case they did not return.

And many didn’t. “Ken Brookmen” was likely Kenneth Brookman, a twenty-four-year-old from Leicestershire, England; he died in 1943 when his plane crashed in a sandstorm in India. “Dick Hovers” may have been Richard Hovers, a twenty-one-year-old from Warwickshire, England, who in 1942 was flying a bomber that never returned to its Gibraltar base; his body was never found. “Gordon Hatherly” was almost certainly a twenty-one-year-old who went on to fly anti-submarine missions out of Reykjavik, Iceland; he received a Distinguished Flying Cross and lived almost into the next century.

Advertisement

August 1, 1942

Cloudy and raining this afternoon. Clair Hope and Otto Groskorth came in after dinner. We went to Town at night, the first Saturday night this summer.

Canada’s implementation of gas rationing in the spring of 1942 meant there were fewer car trips for tourists and hosts alike. But airmen continued to find their way to the Webbs. Clarence “Clair” Hope had met Anita Webb at a party at L.M. Montgomery’s Toronto home, and Anita had invited him to Green Gables should his war travels ever take him to Prince Edward Island. When stationed in Nova Scotia, he hitchhiked to the island while on leave and visited Anita and her family. He returned several times, on this occasion taking along Groskorth, a half-German, half-Canadian airman stationed with him. The time at Green Gables in the middle of the war obviously meant something to Groskorth. He bought a copy of Anne of Green Gables while there, and in it he wrote a note to his parents asking that they be sure to keep it for him; he wanted to read it on his return from war.

November 12, 1942

A nice day. Two English Air Lads came along about 1:30 and I fed them. Homesick nice English lads. After the summer’s disastrous Canadian-led raid on the French port of Dieppe — where 916 Canadians died, many more were injured, and 1,946 were taken prisoner — news turned markedly better for the Allies that fall. The Russians held Stalingrad from the Germans, the Americans and British landed in occupied North Africa, and the Japanese sustained heavy losses at Guadalcanal. For the first time Myrtle could tell her diary, “War news grand.” The tide was beginning to turn.

Meanwhile, off-duty lads — and lasses — kept dropping in to Green Gables. (Myrtle’s diary speaks of several groups from the RCAF Women’s Division.) Their reasons for being there were undoubtedly varied. Some may have read Anne of Green Gables, while others had never heard of it. Some came to golf, others just to walk the course’s rolling fairways. Some seem to have especially appreciated the chats with Myrtle and Ernest, who were old enough to be their grandparents. Some enjoyed palling around with the single Webb girls. The Webbs welcomed them all, regardless of the time of day or season.

Green Gables became so well known as a haunt for military personnel, in fact, that it altered the Parks Branch’s plans for it. The branch had planned not to open the golf course in 1943, having lost a lot of money running it the previous summer, but relented, opening nine of the eighteen holes expressly to accommodate the men and women of the RCAF and the other armed forces members who might come. That decision was renewed in 1944.

November 23–25, 1944

Howard Hurst & Fred Hussey P/O came in the evening for a four-days stay for Howard, two for Fred. Weather not very good on the 24 & 25 but the boys played golf on the 25th in the rain and wind.

As the war slogged on, Green Gables hosted more armed forces personnel as overnight guests. Often, as in the case of Hurst — a young airman from Sarnia, Ontario — the sojourner was someone the Webbs had gotten to know over repeated visits. At other times they accommodated people who had apparently asked them out of the blue about the availability of lodging. “Col. Dodge and wife” stayed for ten days in September 1944, and when they left all that Myrtle could say of these “very quiet nice people” was, “think maybe they were bride and groom.” Nothing in Myrtle’s diary suggests she charged such visitors. The Webbs had boarded lodgers at Green Gables throughout the 1920s and 1930s, but when the government had acquired it in 1937 the Parks Branch had decided not to continue tourist accommodations. Park superintendent Ernest Smith must have known that his friends the Webbs were taking in guests, but whether he told his Ottawa superiors is another matter; there is no discussion of it in the branch’s archival records. Perhaps the bureaucrats turned a blind eye, too.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

May 8, 1945

The war in Germany is over and has been celebrated all across Canada. Halifax had a real riot and millions of dollars worth of damage done in the city by a drunken mob of hysterical people.... I put out a wash in the morning, and Howard Hurst arrived around 5:15 PM.

Myrtle had refused to build up her hopes. In late April 1945, she told her diary that Germany was rumoured to have quit fighting, “but there is no truth in it, not yet.” There was word at the beginning of May of Hitler’s death, “but no one is sure of that.” Even on May 7, she noted cautiously that reports of the war’s end were “not official.” Only on May 8 — victory in Europe day — did she allow herself to succumb to relief. The Webbs celebrated the occasion with their young RCAF friend, Howard Hurst.

This is practically the last of Myrtle’s diary entries about the war. There is no reference to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to VJ day, or to Japan’s formal surrender. The fact that Prince Edward Island National Park had a record season that summer, attracting twice as many visitors as it had two years earlier, suggests that many people were moving on from the war.

As was the national park itself. That November, Smith dropped in on the Webbs and informed them that, since Ernest was turning sixty-five, he would be retired as caretaker and the family would have to vacate Green Gables. From the Parks Branch’s perspective, the transition to peacetime was the ideal moment to ease the Webbs out and to repurpose Green Gables’ role in the park. In internal documents, staff envisioned the whole house being opened as a tourist attraction. The Cavendish end of the park would be given a new caretaker: “Naturally, he will have to be a returned soldier.”

The Webbs were inconsolable. The diary sat untouched for three weeks, and when Myrtle finally did pick it up again she began, “Haven’t felt much like writing.” In letters to her children in Ontario, Myrtle described this period as a nightmare, during which she and Ernest were unable to sleep at night. “Dad seems to have aged so,” she told them. “You cannot have any idea how things have hurt.” Ernest and Myrtle packed up and moved out on a snowy evening in December 1945. There is no indication they ever visited Green Gables again.

Anne of Enduring Renown

L.M. Montegomery’s fiction orphan continues to inspire love and draw crowds

In the spring of 1908, a red-headed, freckle-faced orphan stepped off Matthew Cuthbert’s horse-drawn buggy and into the hearts of readers everywhere. Her name was Anne — with an “e” — and she was the creation of Lucy Maud Montgomery, an aspiring author who lived with her grandmother in Cavendish, Prince Edward Island.

Anne was constantly getting into scrapes. Once she accidentally dyed her hair green. Once she got her friend Diana tipsy on raspberry cordial (she didn’t realise it was alcoholic). Once she hit her classmate Gilbert Blythe with a chalkboard. Rachel Lynde, the village gossip, thought that Anne would never amount to much. But it turns out that Anne has amounted to quite a lot.

Anne of Green Gables launched Montgomery’s literary career, which included seven Anne sequels. The book has been translated into more than twenty languages. It has spawned movies, plays, television series, and Green Gables-themed shops, museums, and merchandise.

Anne of Green Gables – The Musical ran at Charlottetown’s Confederation Centre for the Arts every summer from 1965 to 2019, attracting more than two million viewers and making it the world’s longest-running annual musical production. “For me it’s the story of the power of a young girl’s determination, her belief in herself, and her imagination,” said Adam Brazier, the centre’s artistic director. Anne of Green Gables – The Musical will resume its run at the centre, this time on a biennial basis, beginning in 2024.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement