The Queen's Land

Among Manitoba’s one hundred thousand lakes are eight that have one thing in common: Lakes Prince William, Prince Henry, Princess Beatrice, Princess Eugenie, Peter Phillips, Zara Phillips, Princess Louise, and Prince James are all named after Queen Elizabeth II’s eight grandchildren. The grandkids are the most recent generation of royals to have their names added to the map of Canada, following a centuries-old tradition of naming cities and landmarks after royalty.

The earliest explorers named settlements and landmarks in honour of royalty to stake their country’s claim to the territory. Among the first to do so was French explorer Jacques Cartier, who called the hill overlooking the Indigenous village of Hochelaga “Mont Real” (Mount Royal) after his king, Francis I. The name Montreal lasted to include not just the mountain but the city that later emerged.

A later French explorer named a lake in present-day Manitoba “Dauphin,” in honour of the heir to the French throne. As Britain and France fought for control of North America, settlements received new royal place names or pronunciations.

Royalty who lived in Canada for a time named places after themselves and their relatives. Crown figures who influenced Canada from afar — such as Prince Rupert and Queen Victoria — also had their names added. And royal weddings, births, tours, and coronations all influenced place names. Here are the stories of a few of the colourful majesties on our map:

Port-Royal/Annapolis Royal (For ‘Good King Henry’)

When French merchant and explorer Pierre Du Gua de Monts and his cartographer, Samuel de Champlain, first established a settlement in what is now Nova Scotia in 1605, they named it Port-Royal after France’s King Henry IV, the sponsor of their voyage.

Henry IV reigned from 1589 to 1610 and was known as the evergreen gallant because of his hundreds of mistresses who were willing to overlook his body odour, a combination of “sweat, stables, feet, and garlic.” It was even rumoured that Champlain had been one of his numerous illegitimate children.

“Good King Henry” is said to have been the first leader of a country to promise a “chicken in every pot”: “If God keeps me, I will make sure that no peasant in my realm will lack the means to have a chicken in the pot on Sunday.” Despite his tremendous personal charm, he had to fight his way to the throne during the French Wars of Religion.

French Roman Catholics were unwilling to accept a Protestant on the throne, so Henry IV, a Huguenot, converted to Catholicism, reputedly declaring, “Paris is worth a mass.” He had a successful reign until his untimely murder in 1610 by a knife-wielding religious fanatic who was “prey to visions.”

Meanwhile, in Canada, Henry’s Port-Royal was destroyed by English forces in 1613. Almost twenty years later, the French relocated the community to a spot about eight kilometres upstream from the original site and made it the capital of Acadia. But with the British conquest of Acadia in 1710, Port-Royal and the surrounding county received a new royal name, Annapolis Royal, after Britain’s Queen Anne (who reigned from 1702 to 1714).

The British queen was rather different from the French king in that she was apparently faithful both to her husband — Prince George of Denmark — and to her Anglican religion. While she loved the good life — large meals, drinking, card playing, and opera — this was tempered by a painful gout condition that left her crippled toward the end of her life.

Anne had seventeen pregnancies, but not a single child lived past the age of eleven. The death of her last surviving child prompted the passing of the Act of Settlement, which left the throne to the Queen’s German cousins, the House of Hanover.

Queen Anne’s Annapolis Royal remained a highly contested location. The French, the Acadians, and their Indigenous allies attempted to retake the village several times, and American privateers raided Annapolis Royal during the American Revolution. The town served as Nova Scotia’s capital until the founding of Halifax in 1749.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Cape Henrietta Maria (For a warrior queen)

Welsh explorer Thomas James was searching for the fabled Northwest Passage when he named this remote cape at the northwestern tip of James Bay after the wife of King Charles I (who reigned from 1625 to 1649). Henrietta Maria is notable for being the only queen to be impeached by England’s House of Commons. She was also the daughter of King Henry IV of France and was born in 1609, during the same decade her father sponsored Champlain’s expeditions.

Her marriage to Charles I in 1625 was happy but controversial — he was Protestant, she was Roman Catholic. Family portraits by Anthony Van Dyck emphasized their blissful marriage and family life. In one, Henrietta Maria is shown holding her baby daughter, making her the first queen of England to pose for a portrait with one of her children in her arms. The fact that she was French and Catholic, however, did not endear her to Charles I’s Protestant subjects.

When the English Civil Wars broke out in 1642, Henrietta Maria fled to Holland and sold some of the crown jewels to pay mercenaries to fight in the royalist army. She returned to England with her troops in 1643, styling herself “She-Majesty Generalissima.” The House of Commons, outraged by her behaviour, impeached the queen in absentia. Fearing for her safety, she fled to France in 1644 and remained there for the remainder of the civil war, surviving Charles I, who was beheaded in 1649.

She returned to England in 1660 when her son was restored to the English throne as King Charles II. As dowager queen, she remained a controversial figure. The diarist Samuel Pepys recorded rumours of an affair with her steward, the Earl of St. Albans, and disapproval of her lavish court at London’s Somerset House.

Cape Henrietta Maria, located in what is now northern Ontario, is today the summer home for about two hundred polar bears as well as other migrating wildlife.

Louisbourg (For the Sun King)

The Fortress of Louisbourg was named for one of Queen Anne’s contemporaries, King Louis XIV of France, the longest reigning monarch in French history. The building of the massive stone fortress in what is now Cape Breton began in 1713, just two years before the end of the king’s record-breaking seventy-two-year reign from 1643 to 1715.

Louisbourg was one of the most extensive European fortifications constructed in North America. Built to provide a base for France’s lucrative North American fishery and to protect Quebec from British invasions, the cost of its construction was more than seven times its original budget. The escalating expense prompted Louis XIV’s successor, Louis XV, to jokingly remark that he expected to see its walls rising above the horizon when he looked out a window of his palace.

The Sun King, as he was called, was no stranger to big construction projects. Over the course of his reign, he transformed the royal residence at Versailles from a comparatively modest hunting lodge to one of the most spectacular palaces in Europe.

His cultural impact was not restricted to architecture. The king popularized the ballet, even dancing onstage himself in court performances. He also commissioned more than twenty statues of himself, which stood throughout France to remind his subjects who was in charge.

Louis XIV took a strong interest in the development of New France. Concerned at the slow population growth of French Canada compared to the English colonies to the south, he sponsored hundreds of female emigrants in the 1660s, who became known as “the king’s daughters.”

The Fortress of Louisbourg did not last. The British systematically destroyed it after capturing it in 1758. However, a quarter of the site was rebuilt in the 1960s and 1970s, and the fort is now considered, appropriately enough, the “crown jewel” of Canada’s National Historic Site system. Louis XIV is also honoured in Quebec City, where the Place Royale is named for this famous king.

Fredericton (For a man with a mixed military legacy)

When Loyalists arrived in the 1780s at what was once the site of an Acadian village called Pointe-Sainte-Anne, they named it “Frederick’s town,” for Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. The prince was a skilled military organizer and administrator who initiated many reforms within the British army and founded the Royal Military College in 1802, the forerunner to present-day Sandhurst in the United Kingdom.

As a field commander — Frederick was commander-in-chief of the British forces during the French Revolutionary Wars and the early years of the Napoleonic Wars — he had less success. His defeat at the Battle of Turcoing in 1794 is believed to have inspired a nursery rhyme known as “The Grand Old Duke of York” — its lyrics are proverbial for futile action.

Frederick’s military career came to a temporary end in 1809 when his mistress Mary Clarke was accused of selling military commissions, prompting a parliamentary inquiry. Editorial cartoons soon appeared depicting the British army being run by Clarke, and the salacious details of Frederick’s personal life were published by Thomas Curson Hansard, who had just acquired the right to publish transcripts of parliamentary debates.

Although the House of Commons cleared him of corruption, Frederick chose to resign from his post anyway, only to be reinstated two years later. Throughout the scandal, Frederick’s estranged wife, Frederica of Prussia, stood by him. They had separated soon after their marriage, and she maintained her own stately home filled with pet dogs, cats, and monkeys. Nevertheless, they remained close friends, and Frederick mourned her passing in 1820.

Today, a portrait of Prince Frederick graces Fredericton’s city council chambers.

Charlottetown (For a queen of possibly African ancestry)

The capital of Prince Edward Island was named for King George III’s queen, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. While previous queens acted as leaders of society and fashion, Charlotte preferred a quiet life at the modest Kew Palace outside London with her large family.

George and Charlotte had fifteen children, thirteen of whom survived to adulthood. Just before the arrival of her fourteenth child, an exhausted Charlotte wrote, “I don’t think a prisoner could wish more ardently for liberty than I wish to be rid of my burden and see the end of my campaign. I would be happy if I knew this was the last time.” In addition to her large family, Charlotte had a strong interest in horticulture and contributed to the development of London’s Kew Botantical Gardens.

At a time of rising support for abolitionism in Britain, Charlotte’s ancestry was carefully scrutinized. One of her forbears, a Portuguese noblewoman named Margarida de Castro e Sousa, may have had African ancestry. Charlotte’s portrait painter, Allan Ramsay, supported the abolition of slavery and may have deliberately painted the queen with African features to emphasize this ancestry.

Charlottetown is not the only Canadian place named for George III’s queen. Queen Charlotte also gave her name to the Queen Charlotte Islands off the coast of British Columbia, which were officially renamed Haida Gwaii in 2010. Queen Charlotte City, a small village in Haida Gwaii, still carries her name.

Prince Edward Island (For Queen Victoria’s father)

Canada’s smallest province was named for Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent, the fourth son of King George III. Edward was the first member of the royal family to live in Canada for an extended period of time, residing in Halifax and Quebec City during the 1790s in a military capacity and eventually becoming commander-in-chief of the British North American forces.

During his time in Canada, Prince Edward endeavoured to improve military standards. He commissioned a town clock and parade grounds in Halifax and an improved communication system for the city’s fortified area.

His extensive travels set precedents for future royal tours, and he was the first to describe both English and French speakers as “Canadians.” He is reported to have dispersed a 1792 riot in Charlesbourg, Lower Canada, with the words, “Part then in peace; I urge you to unanimity and concord. Let me hear no more of the odious distinction of French and English. You are all his Britannic Majesty’s Canadian subjects.”

Prince Edward was unmarried during his time in Canada, but he lived with his long-time mistress, Julie de Saint-Laurent. In Britain he could not appear in society with Saint-Laurent, but the British North American elite invited the couple into their homes, and they became close friends with John Graves and Elizabeth Simcoe.

There are numerous Canadian families that claim to be descended from an illegitimate child born to the couple during their time in British North America, but there is no evidence that they started a family in Canada.

After his return to Britain, Prince Edward faced pressure to marry a princess and to father legitimate heirs. Hoping Parliament would pay his debts if he married a suitable bride, he reluctantly ended his relationship with Saint-Laurent and married Princess Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, a widow with two children, in 1818. Prince Edward died of pneumonia just nine months after the birth of the future Queen Victoria in 1819.

Although Prince Edward never actually visited his namesake island, its residents were no doubt grateful for the fortifications he ordered for Charlottetown to protect the city from raids by sea — a frequent problem during the settlement’s early history.

Ontario’s Prince Edward County is also named after the Duke of Kent, as are many other places throughout Canada.

Victoria and Regina (For the Mother of Confederation)

There are more Canadian cities, streets, neighbourhoods, landmarks, and natural features named after Queen Victoria (who reigned from 1837 to 1901) than any other royal personage. Queen Victoria’s birthday, May 24, was celebrated as a holiday in the Province of Canada from 1845 and continued to be a holiday after her death in 1901 to honour her role as the Mother of Confederation.

Victoria never visited Canada herself, but all four of her sons and her daughter Princess Louise (who changed the name of Pile of Bones to Regina to honour her mother) spent time here. In 1843, the Hudson’s Bay Company named a fort on Vancouver Island for the queen. The town of Victoria was founded in 1851–52, becoming the capital of British Columbia in 1868.

Victoria was closely involved in the development of Canada over the course of her sixty-three-year reign. She became queen in 1837, succeeding her uncle, William IV — for whom the Arctic’s King William Island is named. Just months after William’s death, rebellions broke out in Upper Canada and Lower Canada. Amnesties were granted to rebels in honour of Victoria’s coronation the following year.

Victoria met with John A. Macdonald and other Fathers of Confederation in London, and their shared loyalty to the Crown helped to bring the provinces together. The queen also selected Ottawa as Canada’s capital, as it was on the border between English and French Canada and located a safe distance from the American border.

In addition to her political influence, Queen Victoria had a profound cultural impact. White wedding dresses became the norm when she wore one to marry Prince Albert in 1840. She also popularized family Christmas celebrations, seaside vacations, and childbirth anaesthesia (she requested the newly invented chloroform for the births of the two youngest of her nine children).

Author Lucy Maud Montgomery wrote, “When I was a child and young girl the Victoria myth was in full flower. We were brought up to believe that ‘the queen’ … was a model for all girls, brides, wives, mothers, and queens to follow. In those days every home boasted a framed picture of the queen — a luridly coloured photo sent out as a ‘supplement’ by a popular weekly.”

There are at least ten statues of Victoria standing in prominent places throughout Canada, including one at McGill University, that was sculpted by her daughter Louise.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Alberta and Lake Louise (For Victoria’s vivacious daughter)

In 1878, Queen Victoria’s fourth daughter, Princess Louise Caroline Alberta, became the first princess to cross the Atlantic Ocean when her husband John Campbell, Lord Lorne, became the fourth Governor General of Canada since Confederation. For the first time royalty moved into Rideau Hall, and the Canadian public was fascinated by the resident princess.

The Ottawa correspondent for The Times of London wrote on December 24, 1878: “Matters of state pale in popular estimation in comparison with the movements of the Princess. The fact that she has been skating, she has been out walking daily, visiting the Chaudière Falls and city shops, she carries a light cane while walking — these matters call forth lively comments wherever men or women congregate.”

There had already been “lively comments” about Louise’s activities before she left Britain. Louise was the first princess to attend a public educational institution, attending the National Art Training School in London to develop her talents as a painter and sculptor. She was also an advocate of women’s rights, encouraging education for girls and meeting privately with suffragists. And her marriage to Lord Lorne marked the first time an English princess had married a non-royal husband since 1515.

Lord Lorne and Princess Louise encouraged Canadian artists to exhibit their works in Canada, rather than going abroad to the United States or Great Britain, as was the usual practice at the time. They founded the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the National Gallery of Canada, with Louise donating one of her paintings to the collection.

Unfortunately, Louise was injured in a sleighing accident in 1881 and spent long periods of time recovering her health in Bermuda and Europe. Although her absence led to speculation that she did not enjoy Canadian society, she in fact maintained an interest in Canada long after Lord Lorne’s term as Governor General ended in 1883.

There might have been a province called Louise today, except that when the then-district was being named after her in 1882 the princess preferred that it carry the name she had inherited from her father — Alberta. Her other famous namesake landmark — Lake Louise in Alberta’s Rocky Mountains — is known for its quiet beauty and is one of Canada’s best-known tourist attractions.

The princess herself was evidently fond of Alberta. She wrote in 1924, “I am intensely proud of this beautiful and wonderful Province being called after me, and that my husband should have thought of it.”

Queen Maud Gulf (For Norway’s ice queen)

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen named the body of water between the mainland of what is now Nunavut and the southeast of Victoria Island the Queen Maud Gulf for his country’s new queen.

Maud was the youngest and favourite daughter of Britain’s King Edward VII and always made clear that Britain was her true home. She never fully mastered Norwegian and maintained a home on the Sandringham Estate in Norfolk, England, which she visited annually.

Yet there was one aspect of life in Norway that suited Maud: winter sports. When she became queen, she was already an enthusiastic amateur athlete who enjoyed riding and cycling. She also took up skiing, which encouraged other women to take up the sport. Maud passed her love of outdoor pursuits to her son, Crown Prince Olav, who — as part of the Norwegian sailing team at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam — became the first royal recipient of an Olympic gold medal.

Maud was also known for her stylish wardrobe, wearing designer sportswear on horseback and at the top of ski hills. Her love of winter sports was fitting, as her name is attached to some of the coldest regions in the world: Nunavut’s Queen Maud Gulf and Antarctica’s Queen Maud Land and Queen Maud mountains.

Prince George (For George, but which George?)

There have been so many princes named George in recent royal history that there remains debate about which member of the royal family gave his name to the northern British Columbia city of Prince George. Explorer Simon Fraser named the site Fort George — after Britain’s King George III — in 1807. When the city was incorporated in 1915, George V (who reigned from 1910 to 1935) was king.

The second son of King Edward VII, George became king after his elder brother Albert Victor died of pneumonia, George married his brother’s fiancée, Princess Mary of Teck, and in 1901 the young couple went on an action-packed tour of Canada.

Since the name of the city is Prince George, rather than King George, another likely possibility is that it is named after King George V and Queen Mary’s fourth son, Prince George, who became Duke of Kent in 1934. George was the first member of the royal family to cross the Atlantic by airplane, conducting a flying tour of Canada’s British Commonwealth Air Training Plan during the Second World War. George died in a plane crash in 1942 at the age of thirty-eight.

When William and Kate, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, decided to name their first child Prince George, there was a revival of interest in the British Columbia city’s royal history. In 2014, Mayor Shari Green proclaimed July 22 Prince George of Cambridge day, making the future king’s birthday an annual celebration for the residents of Prince George.

Other George-inspired names include Ontario’s Georgian Bay — for King George IV.

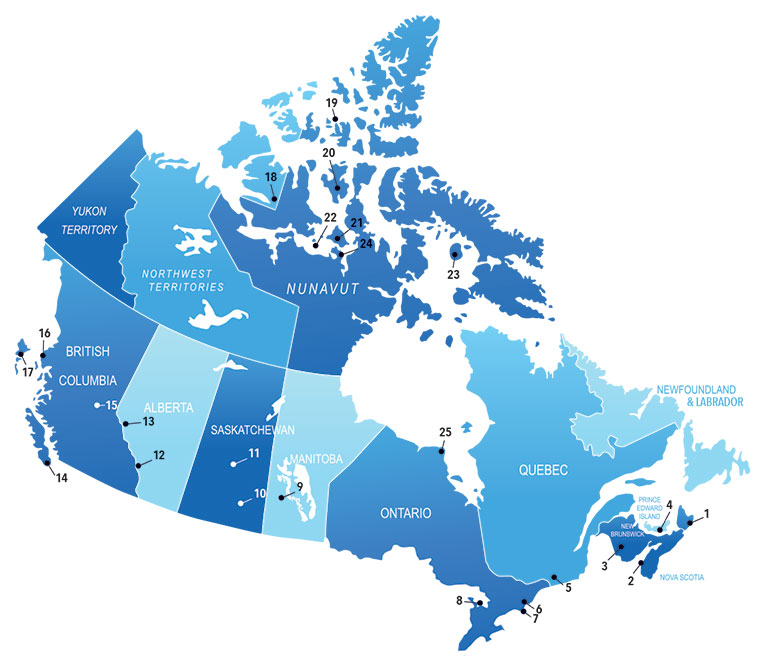

Here are a few of the many Canadian locations named after royalty.

1. Louisbourg, 2. Port-Royal, 3. Fredericton, 4. Charlottetown, 5. Montreal, 6. Kingston, 7. Prince Edward County, 8. Georgian Bay, 9. Dauphin, 10. Regina, 11. Prince Albert, 12. Lake Louise, 13. Queen Elizabeth Ranges, 14. Victoria, 15. Prince George, 16. Prince Rupert, 17. Queen Charlotte City, 18. Victoria Island, 19. Queen Elizabeth Islands, 20. Prince of Wales Island, 21. King William Island, 22. Queen Maud Gulf, 23. Prince Charles Island, 24. Adelaide Peninsula, 25. Cape Henrietta Maria

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!