Canada's Pirate Queen

The sleek sailing ship emerged suddenly like an apparition from the shroud of dense fog hanging over the grey waters of St. George’s Bay, on the west coast of Newfoundland. If the effect was eerie, so too was the appearance of the single-masted sloop. Painted jet black from stem to stern, its name obliterated, it sliced through the fog like a sword.

The ship unfurled its flag — a black pennant bearing a skull above a cutlass — and suddenly, the single broad deck of the sloop bristled with activity as the crew of a hundred men prepared for another day’s dishonest work. They rolled out twelve large guns under the watchful eye of their leader, an imposing figure dressed in a stolen British Royal Navy officer’s uniform and armed with two pistols and a short-bladed cutlass.

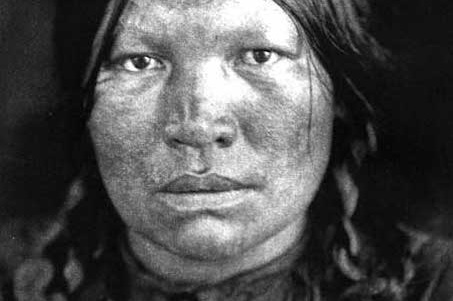

The captain exuded an air of menace — clearly, Maria Lindsey Cobham, Canada’s only “pirate queen,” was not someone to tangle with.

Fact or fiction?

During the “golden age” of piracy that extended from about 1650 to 1720, there were few women at sea. They were considered an omen of bad luck, or at least a potential source of discord among the sex-starved all-male crews.The pirate community was mostly a men’s club. Most had sailed on warships for the English, French, and Spanish navies, only to find themselves out of work when a rare peace broke out. Laws against piracy were lax and difficult to enforce. Indeed, the line between legitimate privateer and lawless pirate was often blurred.

“In wartime, governments licensed privateers to attack their foreign fishing rivals, and in peacetime they turned a blind eye to those who continued, as pirates, to weaken their rivals,” writes maritime historian Dan Conlin in Pirates of the Atlantic: Robbery, Murder and Mayhem off the Canadian East Coast (2009).

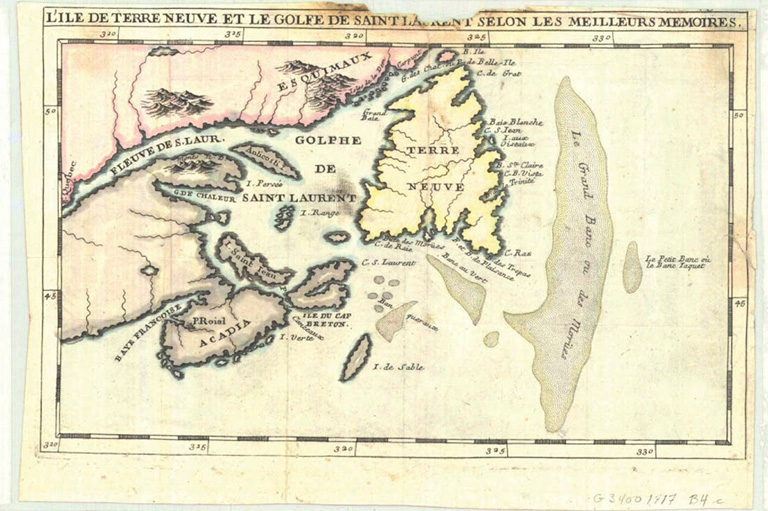

By the time the husband-and-wife team of Eric and Maria Lindsey Cobham came along, the golden age was over. Anti-piracy laws were more vigorously enforced. The Cobhams settled on a hideout on the isolated west coast of Newfoundland in 1740. From there, they conducted raids into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, preying mostly on French ships.

The couple ruled the sea lanes of the region for the best part of twenty years. And they were utterly ruthless. Whereas pirates of the golden age usually killed and tortured a select few sailors of captured ships, letting the rest go, the Cobhams killed everyone to ensure there were no witnesses. After disembarking with their booty, they sent the ships straight to the bottom of the ocean. Since there was no one left alive to explain what happened, the ships were simply listed as “presumed lost at sea with no survivors.”

If one can believe all the tales of Maria Lindsey’s behaviour that are enshrined in maritime folk lore, she demonstrated all the sensitivity of a homicidal maniac. Maria reportedly poisoned the entire crew of one captured ship so she could watch them writhe in agony as the ship went down. On another occasion she was said to have had defenceless seamen sewn into gunny sacks, then tossed into the sea, where they thrashed desperately before they drowned. Another tale has her using captured sailors for target practice.

While some doubt the stories and are even skeptical that the Cobhams actually existed, Conlin, the historian and curator of marine history at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, believes the stories are probably true, but exaggerated.

“If they really attacked as many ships as claimed, the French authorities would have noticed and spent time hunting for them, and there is no evidence that was the case,” Conlin says. “They were most likely ‘wreckers,’ a vaguely defined but vile subspecies of pirates who prey on vessels in distress, murdering shipwreck survivors and looting the wreckage. There was a fair bit of this, to varying degrees, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The Cobhams do fit the pattern of piracy after the golden age of piracy ended in the 1720s — which tended to be small-scale but more ruthless than the big-time pirates of the 1720s.”

The legends of Maria’s cold-blooded exploits are difficult to verify. The Cobhams were evidently never tried in a court of law, thus official records have never been found.

“There are a number of very unreliable secondary popular accounts in different Newfoundland works,” explains Conlin. “The sole source for all this seems to be a boastful, confessional autobiography that Eric Cobham wrote in France on his deathbed in 1780. It is unclear where this document exists.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

A match made in hell

Philip Gosse wrote about the pair in his 1924 book The Pirate’s Who’s Who. By his account, the two met in the seaport of Plymouth, on the southwestern coast of England. Both were in their early twenties and it was a magnetic attraction at first sight — he was drawn to her sexuality, she to his newly minted status as a dashing pirate.

Maria Lindsey was a local girl, but Eric Cobham was born further east along the south coast in Poole, Dorset. He was one of thousands of boys sent out with the fishing fleets to Newfoundland. Not surprisingly, Newfoundland became known as a “nursery school” for pirates-in-training.

Pirates captured their prizes, as a rule, by intimidation and sheer weight of numbers — a merchant crew facing a boarding party that outnumbered them by ten to one had little choice but to surrender without a fight. In this lawless, cutthroat society, it didn’t take Eric Cobham long to forsake the harsh life of the fishing boats for a life of crime. Not yet twenty, he joined a gang of smugglers and then embarked on a new career in piracy. Now all he needed was a partner-in-crime, and he found her in a tavern in Plymouth, serving both drinks and favours to the seafarers.

“Cobham, calling in at Plymouth, met a damsel called Maria, whom he took on board with him, which at first caused some murmuring amongst his crew, who were jealous because they themselves were not able to take lady companions with them on their voyages,” wrote Gosse.

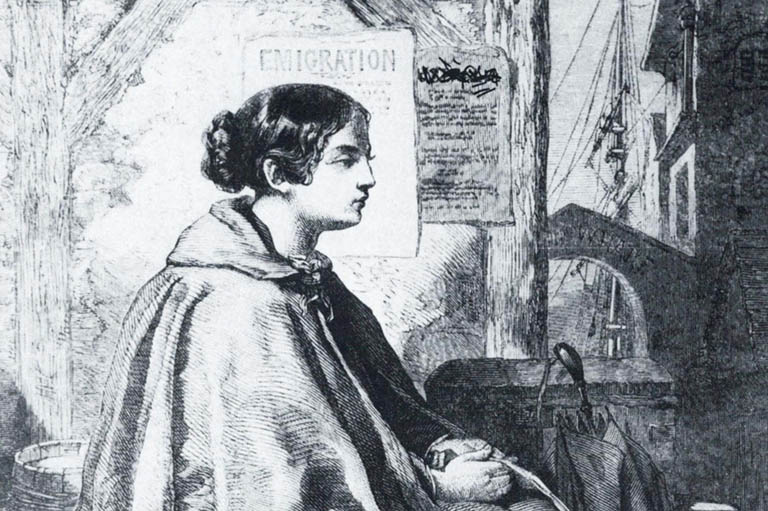

Piracy offered everything to Maria that was denied to her on land in Plymouth, not least an escape from the bleak careers of prostitute and scullery maid.

As a pirate, she had freedom and independence, kept her own hours, and spent much of her time gambling at cards, drinking rum or porter (dark ale), and eating choice food. Killing and plundering provided additional excitement.

While she may have followed her lover into this life of crime, by all accounts she did not play second fiddle to him — Maria was the one really wearing the pantaloons in this pirate family.

They never walked down a church aisle, but Maria Lindsey and Eric Cobham formed a partnership that lasted the rest of their lives, rooted in a bloodthirsty pursuit of excitement and untold riches.

Their first venture took them towards Bristol, the west coast port that eclipsed even London in the volume of its commerce. While there, the Cobhams were said to have hijacked a merchant ship and made off with 40,000 pounds sterling in notes and coin.

Crossing the Atlantic to Nantucket, Massachusetts, they captured a fast sloop and sailed their new ship northward until they found their way past the tip of Cape Breton Island.

Here they hit the jackpot, a rich and vulnerable supply route that came through the Gulf of St. Lawrence — part of a trading triangle that saw ships coming to Newfoundland loaded with salt and provisions, taking salt fish back to the Mediterranean countries, then heading home to England with wine, olive oil, and dried fruits. The later addition of furs to the ships’ cargoes made this an even richer hunting ground that was virtually untouched by other pirates based in the Caribbean.

“The English Channel becoming too dangerous for Cobham, he sailed across the Atlantic and lay in wait for vessels between Cape Breton and Prince Edward Isle, and took several prizes,” Gosse wrote.

All the Cobhams needed now was a safe haven — a harbour to hide their ship and a good place for careenage. (Because no dry dock was available to them, pirates careened or beached their sailing vessel on a sandy beach at high tide to expose one side of the ship’s hull for maintenance below the waterline once the tide had gone out. Tarring the hull reduced the ever-present leakage problem; removing barnacles increased the ship’s speed.)

The pirate queen and her consort chose their craft well. Although smaller than a man-of-war, their sixty-five-foot-long sloop drew a shallow draft of only eight feet, meaning it could go into waters where larger navy ships could not follow. The sloop was extremely seaworthy and could outrun almost any ship afloat.

The harbour the Cobhams chose for their careenage was far enough north of the shipping lanes to be safe from discovery, but within two days’ sailing of both the Cabot Straits and the Strait of Belle Isle. No navy warship could follow them into Sandy Point, at that time a two-kilometre-long sandspit on the west coast of southern Newfoundland that reached into Bay St. George. (Today it is a deserted island, marooned by erosion from the sea.) Big ships could not get past the shoals that guarded Sandy Point.

The goods they stole were “laundered” in Perce, on the Gaspé Peninsula, where legitimate trading ships picked up the contraband cargo and transported it past the gauntlet of Royal Navy warships to France. The booty was sold in French “free ports,” where local aristocrats ran a massive black market.

The black sloop ambushed one ship after another. Murder and mayhem continued apace.

“Maria ... took her part in these affairs, and once stabbed to the heart, with her own little dirk, the captain of a Liverpool brig, the Lion, and on another occasion, to indulge her whim, a captain and his two mates were tied up to the windlass while Maria shot them with her pistol.... In fact, she entered thoroughly into the spirit of the enterprise,” wrote Gosse in The Pirate’s Who’s Who.

Maria was known for always wearing a British naval officer’s coat, according to David E. Jones’ 1997 book Warrior Women. Jones writes that she took it from a young officer who was captured during a raid on a Royal Navy ship.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

“She had him stripped on deck. After running the hapless young man through with her sword , she donned his uniform, a costume that became her trademark. When the original became tattered she ordered new ones made from its pattern.”

Maria’s crew was made up mostly of defectors from the fishing fleets or the Royal Navy. The navy crews were not difficult to recruit. Many had been press-ganged into service and were not allowed to leave their ship for up to two years, in case they deserted. The naval ships were often damp, dark and filthy, and the food crawled with maggots. Little wonder that Dr. Samuel Johnson described this life at sea as little better than “being in a jail, but with the chance of being drowned.”

Forsaking the king to serve with the pirate queen simply meant unlimited booze rations, fewer floggings, and better food.

Maria and Eric defied the odds, evading capture for two decades. In the end it was Maria’s husband who called a halt to their life of crime. Tired of living life on the run and now fabulously wealthy, the Cobhams packed away their pirate gear and set sail for France. There, they sold off their fleet of ships and cargo and bought a fine estate near Le Havre from the Duc de Chartres.

They now had a private harbour, servants, and a secure place among the landed gentry of French society. Somewhere along the way, they also raised three children. Eric Cobham reinvented himself as a wealthy landowner and a pillar of respectability, completing a marvellous transformation by actually becoming a magistrate and then a judge in the French county courts. He held this lofty position, passing sentence on some former contemporaries, for twelve years.

In middle age, the ex-pirate couple gradually drifted apart. Eric took to almost public wenching, while Maria took to alcohol, often laced with laudanum, an opium-based painkiller. As Eric developed a reputation as a Casanova, Maria became reclusive, and quite possibly insane.

A suicide leap

One day, Maria simply disappeared. A large-scale search was launched, and after two days of combing the coastline, her body was found in the sea directly below a sheer clifftop near the Cobham’s chateau.

An autopsy revealed traces of poisoning. “Maria, it was thought, possibly owing to remorse, poisoned herself with laudanum and died,” Gosse recounts.

It wasn’t long before Eric Cobham took to his own deathbed and called for a priest so that he could make a lengthy confession about the Cobhams’ life of piracy. The old man’s rambling discourse was duly recorded, and after his death the priest kept his promise by getting the slim volume published.

It was a literary event not welcomed by the Cobham’s three children. They were horrified by the disclosures and stunned by the discovery that their apparently respectable parents had been a pair of ruthless buccaneers. In an attempt to suppress the book, the children are said to have bought up every copy and had them burned.

But one fragmentary first draft copy is said to have found its way into the Archives Nationales in Paris, where it has remained hidden from view for the past century.

Was Maria Lindsey Cobham’s devilish life fact or fiction? Since she evaded capture — and with it, the scrutiny of a court trial and transcript — she remains an enigma.

Historians do concede that if her tale is true, then Maria Cobham would likely have been the only female pirate to have terrorized Atlantic Canada.

Her exploits are still passed down from one generation of salty dogs to the next. Shiver me timbers, there’s nothing quite like a good pirate yarn.

Lethal Lasses

Was piracy an exclusive men’s club? Hardly. These women raided, robbed, and ruined with the worst of them.

Alvilda

According to a twelfth-century Danish document, Gesta Danorum, Alvilda was the daughter of a ninth-century Swedish king. She ran away from an arranged marriage to join a crew of young women pirates who were all dressed as men. She and her crew prowled the Baltic Sea and soon joined forces with a group of male pirates who had lost their captain. Elected the leader of both crews, Alvilda preyed on merchant ships. According to legend, Alvilda was finally bested in a sea battle by Alf, the Prince of Denmark, the man she was supposed to have married in the first place. This time she accepted his proposal.

Anne Bonney

The illegitimate daughter of a rich Cork businessman and his servant maid, Anne Bonney grew up in the early 1700s on a wealthy plantation in the American Carolinas. She refused her father’s orders to marry a rich husband and was disowned after tying the knot with a penniless sailor. She later dumped her husband for rakish pirate captain John Rackham. Wearing men’s clothing, she sailed with “Calico Jack” in the Caribbean and helped capture many ships. She was caught by authorities near Jamaica in 1720. According to the 1855 tome The Pirate’s Own Book by Charles Ellms, she was pregnant when tried and, unlike her husband, was spared execution.

Mary Read

A crewmate of Anne Bonney, Read was also an illegitimate child. According to The Pirates Own Book, her single mother raised her as a boy. She had a robust constitution and served with distinction as a soldier, marrying one of her comrades. After he died, she went to sea, bound for the West Indies. Read eventually joined the crew of Calico Jack. She met Bonney and they forged a lasting friendship over many misadventures. Read was captured in 1720 along with Calico Jack, Bonney, and the rest of the crew. Like Bonney, she was pregnant when tried and her execution was delayed. She died of illness before she could be executed.

Madame Ching

Described in the 2004 book Pirates and Buccaneers by Gilles Lapouge as “an uncouth woman with a face like a bear,” Madame Ching terrorized the coasts of southern China in the early 1800s. The widow of the pirate captain Ching-Yih, Madame Ching had a knack for knavery, growing her dead husband’s fleet to more than 2,000 ships. By the end of her career, she was the undisputed naval power in the region. She managed to negotiate pardons for herself and her fleet from the Chinese emperor, and was given part of the imperial fleet to command. She retired a wealthy woman and died in 1844.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!