Against the Current

Bewdley, Ontario 1904

A sharp knock disturbs my morning mending. The messenger at my door asks, “Mrs. Hubbard?” I nod, heart pounding, and accept the telegram he holds out. Telegrams are as rare as hen’s teeth around here, and just as alarming. The flimsy piece of paper trembles in my shaking hands as I read 10 words that change my life:

Mr. Hubbard died October 18, in the interior of Labrador.

Freezing water fills our canoe, soaks through my wool stockings and steals my breath. I bail as fast as I can and ask myself how I, Mina Benson Hubbard, teacher, nurse and widow, came to be on this adventure through the most remote and unknown part of Newfoundland, the Labrador Peninsula.

“We’re fine now, Mrs. Hubbard. You can stop bailing.” The voice of our Cree-Scots lead guide, George, floats forward from the stern of our canoe, letting me know that we have successfully run the rapids, and that I can rest. I pick up my expedition journal and keep on with my map of the shoreline. As I sketch in bogs and channels, sandbars and cliffs, my mind drifts back to the birth of this journey. As with everything in my world back then, it all began with dear Leonidas Hubbard.

I remember that particular evening, my husband’s face shining with joy at the dinner table. “I can begin my Labrador expedition!” he crowed.

“Wonderful!” I said. “When do we leave?” We had, after all, planned and travelled together on every canoeing and hiking trip his work as a writer for an outdoor magazine required. I could see no reason to stay home for his most exciting journey so far. But my Leon took a different view.

“This is a man’s trip, Mina, through a land of no mercy! There will be hardships, rough living, even brushes with death! I couldn’t live with myself if anything were to happen to you.”

Who knew, at the time, that death would not brush by Leon, but take him? George, who was also the guide on Leon’s trip, came to visit me. He told me the sad story of their trip, his big shoulders shaking with grief as he spoke.

From the beginning, luck ran against their expedition. Leon’s team missed an important turn on the second day, and ended up not only lost, but off any known map. Days became weeks. Rations ran low and so did Leon’s strength.

Too weak to go any farther, Leon was left at camp while the other two men went to seek help. A 10-day blizzard slowed their return. By the time the rescue team reached the camp, Leon had gone to sleep in his tent and never awakened.

Leon’s dream of crossing the Labrador Peninsula by canoe is now my dream. If anyone should finish the Hubbard Expedition, it must be me, his partner. I vow to return to Labrador. There and then, I pick up Leon’s notes and get to work.

I plan to the smallest detail, pack extra everything, hire more guides. Live and learn, the old saying goes. I must learn from Leon’s mistakes so I may live.

June 27, 1905

We start our journey from the Hudson’s Bay post at the southernmost point of the Nascaupee River, our goal to canoe and hike overland more than 500 miles, up the peninsula to our final stop, Ungava Bay, in just two months.

Our time is short, but the days are long under the northern sun. Sunlight lasts for 20 hours before dimming, and our team uses every minute of it to paddle, portage, make and break camp, and last but not least, fulfil my personal mission to map this mysterious wilderness.

How can one map this land? Its time and history are mind-boggling. My guides say there isn’t a rock, river or mountain that doesn’t have its own spirit. Indeed, the spirit of the land strengthens me. I stride along the cliff top, towering twice as tall as trees twisted from years of strong winds and feel as mighty as a moose.

Then I follow a mere hint of a path through dark forest, dwarfed by steep cliffs and high waterfalls, and startle at the smallest sound. I feel as small as a house fly. Or indeed, a housewife … My ideas and opinions were often swatted away back home, like an annoying insect, and I felt tiny and unheard. If I am not dwarfed by the staggering size of my goal, if I indeed complete this trip and return home victorious, never again will any man dismiss me with a wave of his hand.

For weeks, we paddle north through the unknown. I aim my sextant at the horizon daily to check our position. I map and photograph our amazing journey to prove two important things. First, that a “mere woman” can conquer Labrador, and second, that no one else will die trying. Everyone will, at last, have a true map to find their way.

August 1905

With the help of my skilled guides, I have travelled mountains and rivers no woman like me has travelled and seen things no woman like me has seen. Herds of caribou on migration, a rippling rug of hooves, hides and antler that sound like summer thunder. Modern-day nomads, living in shelters of skins and furs only as long as the bounty of berries and small game lasts, then moving on.

Our crew has suffered over every inch of trail, been drenched in rapids, and driven insane by blackflies. Lemmings ate my only hat.

One bright morning, we crossed the height of land and rode the river. At first, we were like ski champs, our canoes slaloming around boulders. We then picked up speed like a runaway toboggan. The narrow gorges widened, the cliffs fell away, and we were at last drifting on a large body of water as calm as a washtub. Ungava Bay! Hallelujah!

Many moments on this trip, I wished I were a man. But not this one. This I will enjoy fully as a woman. I am the first outsider to cross Labrador by canoe, and I have the maps to prove it.

Rest well, my dear Leon. I found the way and our work is done.

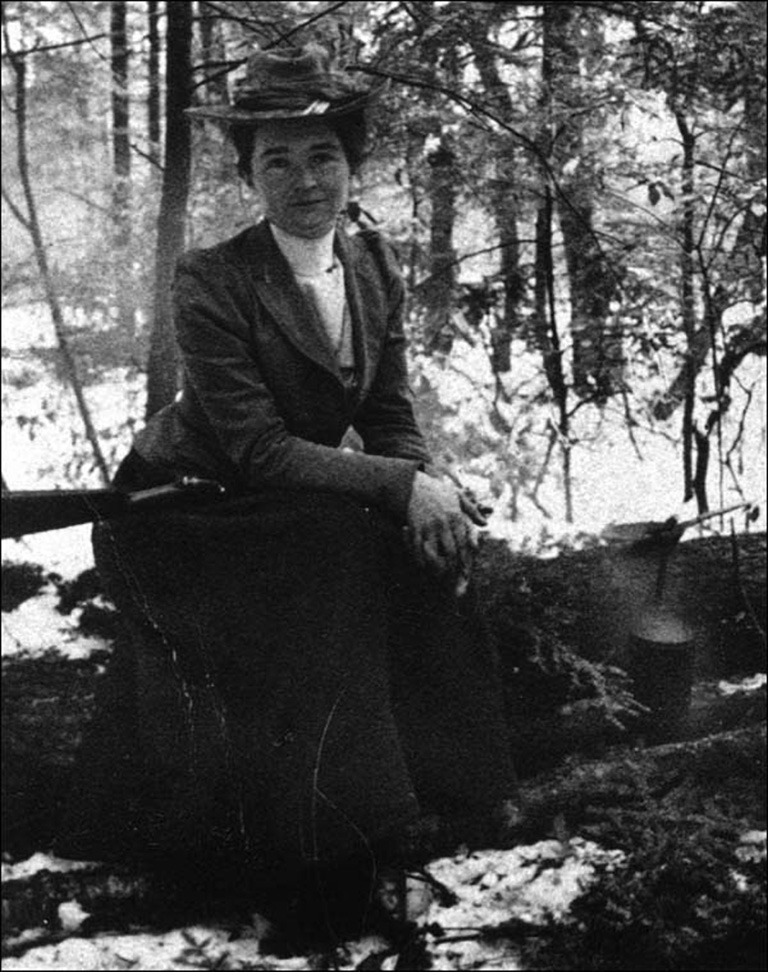

Travelling with wool clothes, heavy canvas tents and wooden canoes, Mina Benson Hubbard and her Indigenous guides accomplished what no other team had — they navigated and mapped a route through Labrador’s Upper Peninsula.

Mina was working as a nurse when she married an adventurous writer named Leonidas Hubbard Jr. On his last trip, through Labrador by canoe, his team paddled the wrong way and ran out of food. When winter came, Leonidas died.

In 1905, Mina decided to try the same journey. She used a tool called a sextant (it measures the angle between the horizon and the sun) to correctly navigate their route. Her guides were expert woodsmen, but Mina helped by catching lake trout, repairing broken equipment and baking bannock over their campfires.

Mina’s expedition was a roaring success. She pinpointed the positions of the Naskaupi (she spelled it Nascaupee) and George rivers, information that would have saved her husband’s life. Her map became the official one for the area until aerial photography came along in the 1930s.

By charting her way through Labrador, Mina honoured her husband’s dream and at the same time became one of the first Canadian women to create detailed written maps.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive features both English and French versions of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids — 3 digital issues per year for as low as $13.99. Tariff-exempt!