In My Yesterday

After my parents moved to a retirement residence, I was tasked with clearing out my childhood home. While I expected to encounter the usual junk drawers full of knick-knacks, I was surprised to uncover objects that would prompt the beginning of my next artistic project and the unravelling of my — blurry to me — family history. Parts of my family’s story had been dropped in bits and pieces into conversations I’d overheard when I was a child, but it had never been told to me directly. While clearing out the house, I unearthed artifacts, documents, and photographs that revealed the story of the beginning of my ancestors’ journey from their tiny village in Hoi Ping, China, to a life in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

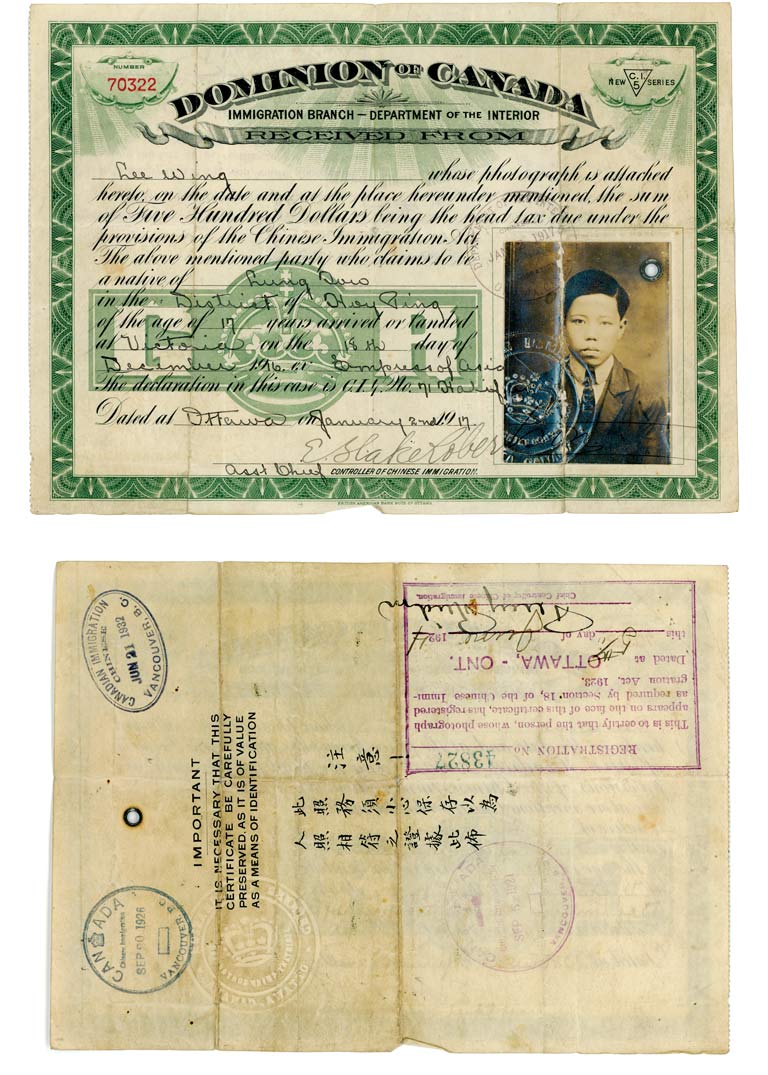

One discovery was tucked in the corner of the attic: laundry bags from my grandfather’s business, stuffed with brown striped paper used to wrap clean laundry in neat packages to return to customers. A significant discovery was my grandfather’s head tax certificate of 1917 — evidence of the fee that, beginning in 1885, was imposed exclusively on Chinese people to discourage them from becoming Canadian citizens, even though thousands of Chinese men had endangered their lives while building the Canadian Pacific Railway. Through speaking with my relatives and finding documents written by my father, I learned that his grandfather — my great-grandfather — had also lived in Canada and had worked on that same railway. The understanding of my Canadianness changed completely at that point. This discovery meant that, although my siblings and I were the first generation to be born in Canada, our Canadian heritage is four generations deep.

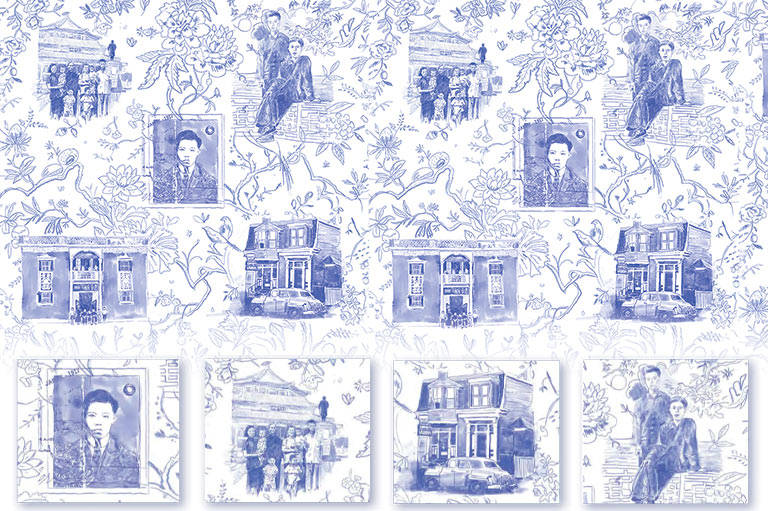

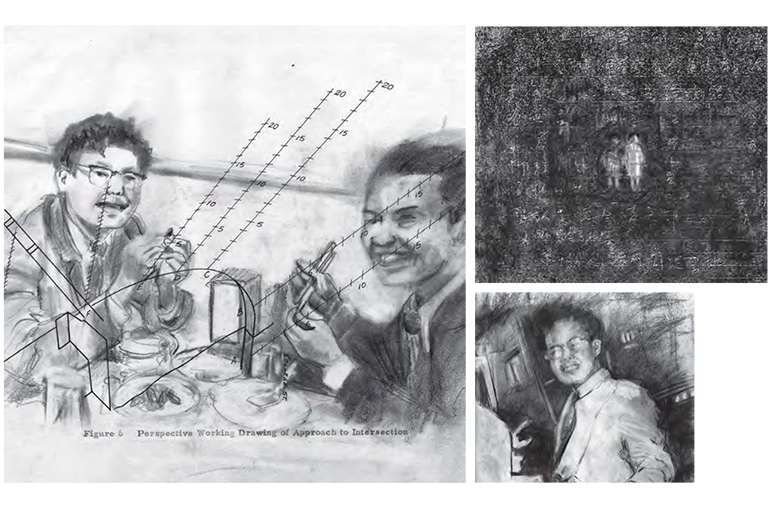

With my father’s progressing Alzheimer’s, I wanted to capture what unknown familial history I could — a desperation that became even more acute after my mother’s passing in 2022. My research unfolded through my art practice, and the history materialized as I drew the found objects and photographs on the writing paper, graph paper, and laundry paper I’d found in the house.

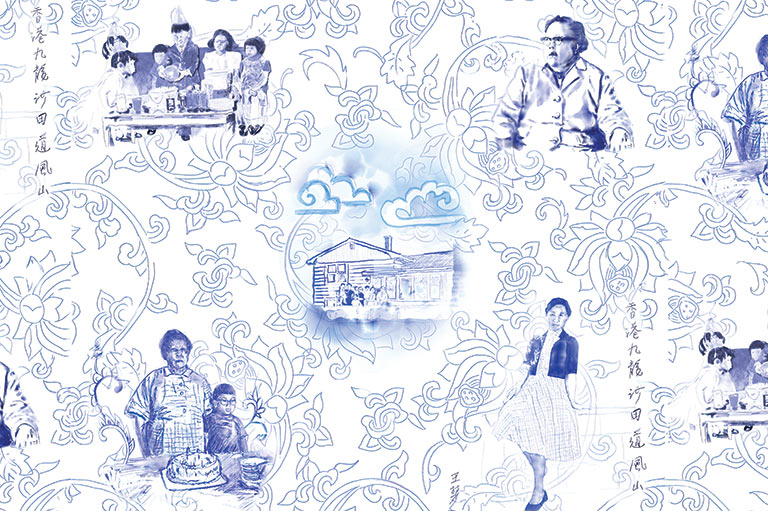

I wanted to tell this story visually as an immersive installation: a montage of photographs, drawings, animation, and audio paired with the found artifacts. The installation opened at the Pier 21 Museum of Immigration in Halifax on May 13. It is a visual palimpsest, with different areas experienced as chapters of a longer narrative. Here are some of the stories, photographs, and drawings.

From Hoi Ping to Halifax

My great-grandfather Reng En Lee was an industrious individual from a small village near the South China Sea. He was a street peddler and carried his wares in two woven baskets hung on either end of a bamboo pole that he balanced on his shoulders. Mr. Fong from the neighbouring village recognized that my great-grandfather was a sincere hard worker and was so impressed with him that he said: “You should go to Gold Mountain.” In the late nineteenth century, this was the name given to North America for its promises of riches.

Great-grandfather said, “No, thank you, I can’t afford it.” But Mr. Fong said, “Don’t worry, I’ll help you,” and he offered him three hundred Canadian dollars to pay for an immigration certificate, the head tax, and the fees for boarding a boat to Canada. Reng En Lee was one of the first people from his village of Long Tow to go to Canada. He laboured hard on the railway to send money home to his family, before eventually returning to China.

In 1917, Reng En Lee’s son James Tue Lee boarded the ocean liner Empress of Asia and made the same month-long journey across the Pacific Ocean, then continued by train across Canada to Halifax. At the age of seventeen, he paid the five-hundred-dollar head tax — equivalent to over ten thousand dollars today — because, like many Chinese emigrants, he was seeking a better life for his future family. Around this time, many Chinese people left their homeland because of war, famine, and floods. The year James Tue Lee arrived, the Halifax explosion devastated entire neighbourhoods of the city; two years later, race riots against Chinese people erupted. I wonder what my grandfather thought about his decision to move to Canada.

Charlie Wah Laundry

Beginning in 1927 my grandfather James Tue Lee, along with two other men from his village, ran a laundry business on Barrington Street in Halifax. It had huge tables for ironing sheets, a hot drying room with cedar-lined walls, and a kitchen in the back for family members and workers to take their meals. In 1920 my grandfather went back to China to get married to my grandmother Hoi Lee. But before she could join him in Canada, the federal government in 1923 passed the Chinese Immigration Act (known informally as the Chinese exclusion act), forbidding virtually all Chinese people from entering the country. My grandfather worked hard to save up for the long trips back and forth to China to see his wife. In 1925, their first child, a daughter, was born. Her name was Hui Lan Lee, but I later knew her as my Aunt Di Goo.

Family reunited

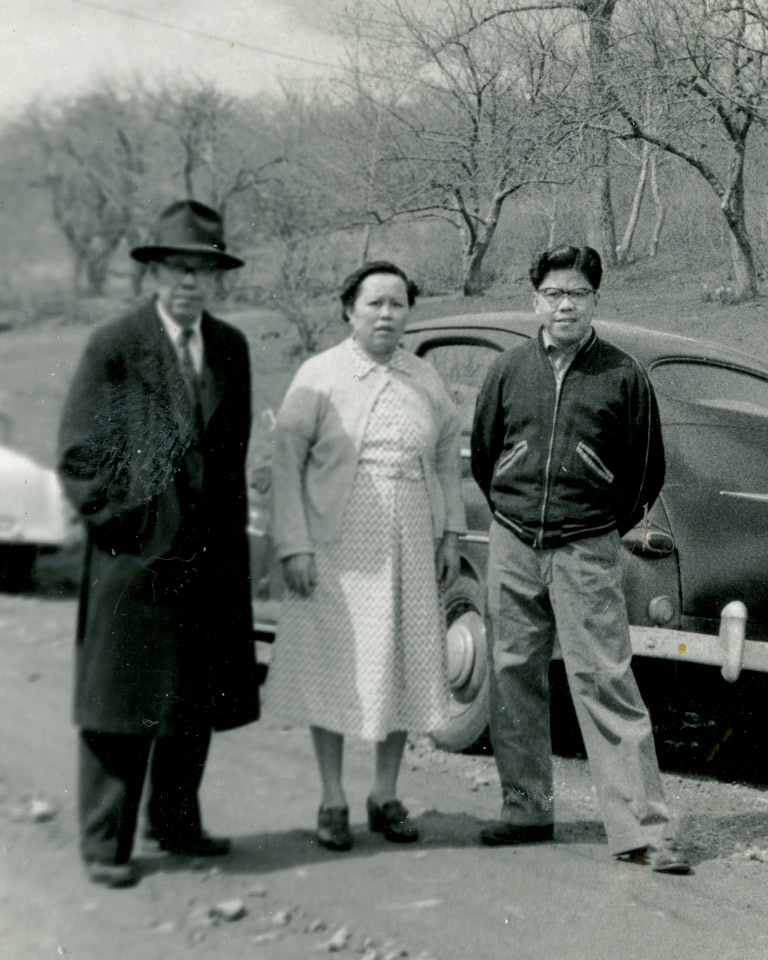

In 1947, the Chinese exclusion act was lifted. Finally, twenty-seven years after their wedding, my grandmother and my grandfather could be reunited. Their daughter, Hui Lan Lee, who had grown to adulthood, remained in China. But my grandmother brought with her their son — my father, Chew Sen Lee, whose given English name was Fred.

I discovered my father’s telling of his immigration story in reminiscences he had started writing: “In everyone’s life, there are moments and events that occurred that will leave unforgettable impressions,” he wrote. “On August 16, 1945, I was thirteen years old and was standing with a large crowd of country people in the small market town listening to the announcement by an elementary school principal, Mr. Kung Kai Ci. [He] said: ‘My dear fellow countrymen, I have good news for you. Japan has surrendered after the Americans dropped two atomic bombs on their soil, one in Hiroshima and one in Nagasaki.’ The re-establishment of communication between my father and me could be resumed. A little over 4 years from that date, I was on my way to Gold Mountain, to see my father and start a new life.

“It was January 8, 1950. I boarded a Canadian Pacific Airline’s North Star airplane with my mother [and] my cousin Nancy Dai Sum, headed for Canada. It was a four-engine, turbo-prop aircraft, which had to stop over in Tokyo overnight and make a refueling stop in Alaska before reaching Vancouver. It was incredibly expensive. A one-way trans-Pacific trip per person cost the equivalent of a man’s wages for 6 months.

“When we boarded the plane, I was very apprehensive about its safety. My palms were wet with sweat, praying silently that our passage was safe. Then after about 90 minutes into the flight, when we were over Taiwan, the captain announced, ‘We are returning to Hong Kong because of engine trouble.’ I looked out the window and saw, sure enough, one of the four propellers was not working. I was never so scared in my life and wondered whether I should continue my trip to Canada. ln Alaska, I saw snow for the first time. It looked so pure, white, and fluffy. I could not wait to get to Canada and play with it. I changed my mind about it very quickly when I really had to deal with it.”

Although my dad spoke no English when he arrived as an eighteen-year-old, he studied hard to become a civil engineer and worked as the director of traffic for the Nova Scotia Department of Highways. His older sister, my Aunt Di Goo, didn’t come to Canada until 1983, nearly twenty years after her father had passed away.

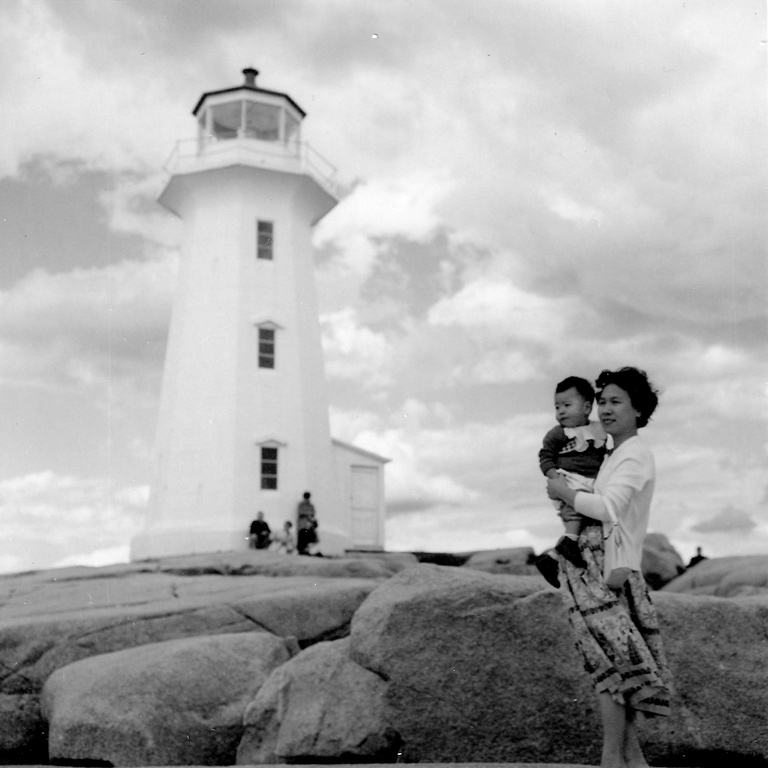

Trans-Pacific courtship

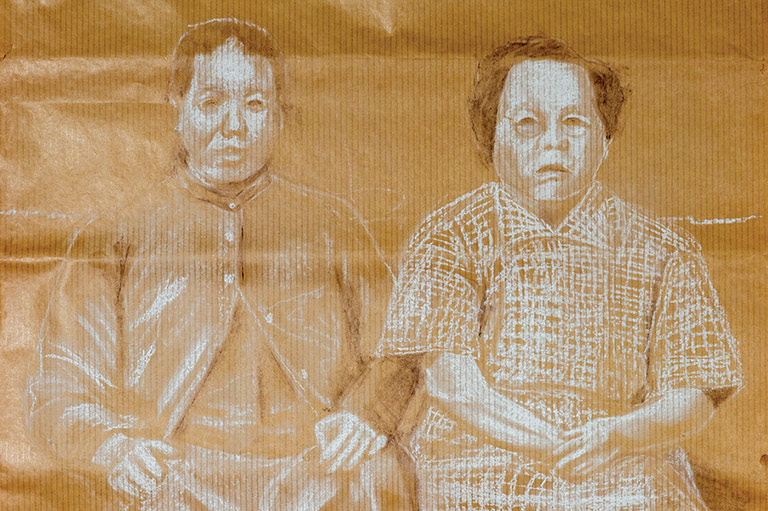

My mother, Chor Han Lee (née Wong), whose given English name was Miranda, was the eldest of five children. She was a diligent student until her elementary education ended due to the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in 1941. She taught herself how to sew and started working to make money for the family by embroidering the names of sailors from Britain’s Royal Navy onto their uniforms. After the war, my mother obtained degrees in nursing and midwifery and started working at a hospital.

Her best friend, Linda, and Linda’s boyfriend, Arthur, decided to set her up with Arthur’s cousin Fred in Canada. They courted overseas, sent photographs, and wrote countless letters in Chinese and in English. In 1957 they married in Hong Kong, and then had a reception in Halifax at the restaurant where my dad worked while he went to school. They had been married for sixty-four years and shared a love of ballroom dancing before my mother passed away in 2022. I found some of their letters as I was clearing out the house:

October 9, 1956

Dear Miranda,

I have just received several letters and some photographs from you. They all make me happier in a sense that they tell me you are a very righteous girl … with an independent spirit … as well as a helpful attitude toward fellow human beings, especially members of your family. Though I only know you for a short period of time, you seem to be my old friend. This is probably due to the fact that I have been thinking a lot of you.… In fact, I have been thinking of you more than anybody else so far in my life.

— Fred

March 23, 1957

My Dearest Fred,

I have received your letter in English and some pictures. I like them very much. Oh! You are very handsome, dear.

— Miranda

My brother Edmund was born in 1958. To have the first-born be a son in Chinese culture is significant. For the expanding family, my grandfather took the money he had saved up over the years and bought a house near the laundry. He lived there with my grandmother, my parents, Edmund, and, soon, my sister Bonny.

My grandfather passed away in 1964. Two years later another tragedy occurred. Edmund, aged eight, was riding a bicycle on his way to school when he was hit by a bus and died. When I was cleaning out the attic, one of my most heartbreaking finds was a suitcase full of little boys clothes, many new and still in their original packaging. It pains me to think that my parents hung onto this for fifty-five years until I discovered it.

New beginnings

Devastated by Edmund’s death, my parents moved to a house in a safe postwar subdivision where all the homes faced each other, embracing walking paths, a playground, a field, and a school that could be accessed without crossing the road. The backs of the houses faced the streets, which were named after fallen soldiers.

Our split-level housed eight people: five kids, two parents, and my grandmother, packed two by two into tiny bedrooms. Dishes clanging, two dialects yelling, kids stomping. There were two humble tables in the corners of the living room. You wouldn’t even know they were shrines, save for the portraits and a little brass vase for incense. On my grandfather’s shrine there was a round green ashtray that had a button you could push to swirl away the tobacco ashes. On it sat a pipe. On my brother’s was a small photograph of him smiling. After my grandmother passed, a teacup and saucer set — the British kind — was added and filled with fresh tea daily. Every day, incense was lit, and slowly it would burn and leave a single tower of ash, balanced perfectly until it fell into the saucer beneath. One day I was so fascinated by this precarious tower of ash that I reached out and touched it. It fell to the ground and left a burnt line in the 1970s yellow-gold carpet.

Dinnertime meant bowls of rice, duck, bok choy, steamed fish, and soup every night as the setting sun streamed into picture windows facing what my dad called “a million-dollar view.” We learned quickly that chopsticks were not drumsticks, but that didn’t stop us from pretending we were walruses, chopsticks dangling from the corners of our mouths.

What occurred in the safety inside our home was not the same outside. Once, rotten eggs were thrown at the picture windows. They froze, and my mother got a ladder and scraped them off. Another time, “Chanks” was spray-painted on the path in front of our house. I was always amused by the misspelling of this racial slur. Although the school was so close you could hear my grandmother yelling at us from the backyard to put a sweater on, sometimes that two-minute walk was peppered with name-calling: “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees, if you please!” Kids pulled at the corners of their eyes to try to imitate the shape of ours. Some days I would stay long after the bell rang to wait until the teenagers had gone, before I ran home. “Mummy mummy! They are making fun of me again because I am Chinese!” She’d reply, “Just ignore them. They’re jealous.” As I learn of the incredible bravery and resilience my ancestors showed in coming to a new country, I am realizing that there is nothing to be ashamed of, and, in fact, I’m deeply honoured and proud of my heritage.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!