Fractious Farming at the Furtrade Posts

PEMBINA RIVER POST—30th April 1804... Grande Gueule Stabbed Capot Rouge, Le Boeuf stabbed his young wife in the arm, Little Shell almost beat his old mother’s brains out with a club, and there was terrible fighting among them. I sowed garden seeds.

So wrote Alexander Henry the Younger in the post journal. Not that he was a specially eager beaver in gardening. It was a pursuit at most of the fur-trade posts from the very first, but with varied success.

Article continues below...

-

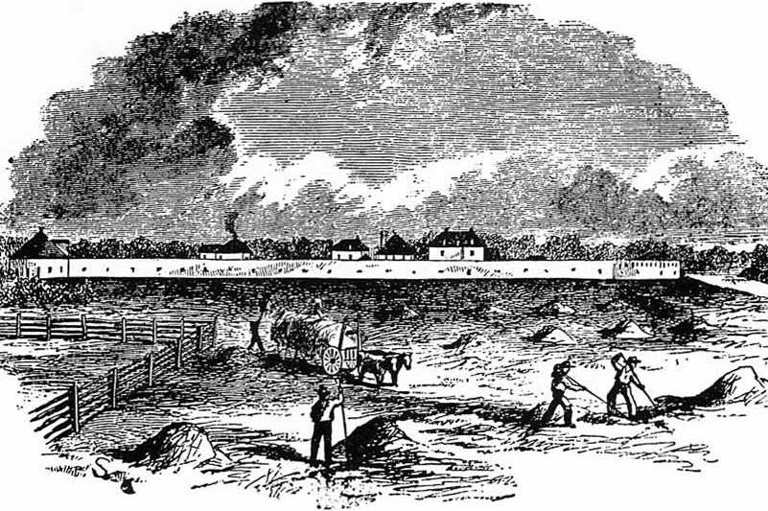

Haying at Lower Fort Garry, 1860.

Haying at Lower Fort Garry, 1860. -

Views of the garden planted by Mr. and Mrs. J.J. Wood at Moose Factory.The Beaver Collection

Views of the garden planted by Mr. and Mrs. J.J. Wood at Moose Factory.The Beaver Collection -

Views of the garden planted by Mr and Mrs J.J. Wood at Moose Factory.The Beaver Collection

Views of the garden planted by Mr and Mrs J.J. Wood at Moose Factory.The Beaver Collection -

Views of the garden planted by Mr and Mrs J.J. Wood at Moose Factory.The Beaver Collection

Views of the garden planted by Mr and Mrs J.J. Wood at Moose Factory.The Beaver Collection -

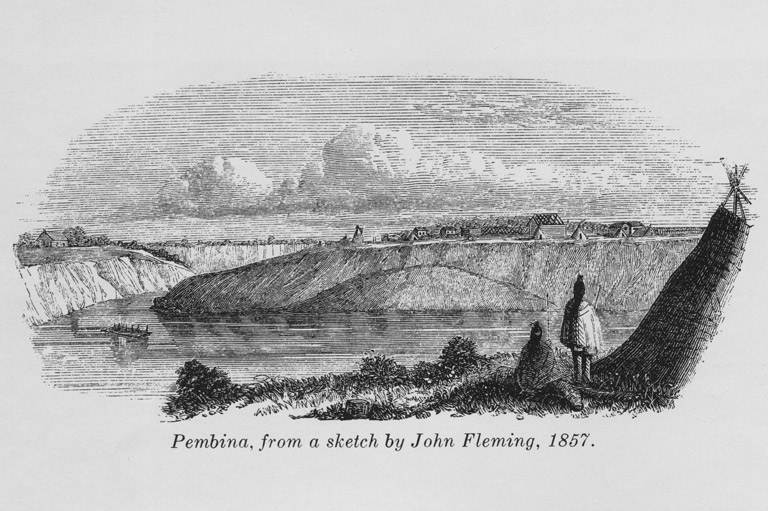

Pembina, from a sketch by John Fleming, 1857.

Pembina, from a sketch by John Fleming, 1857. -

Vegetable garden at York Factory, 1880.The Beaver Collection

Vegetable garden at York Factory, 1880.The Beaver Collection -

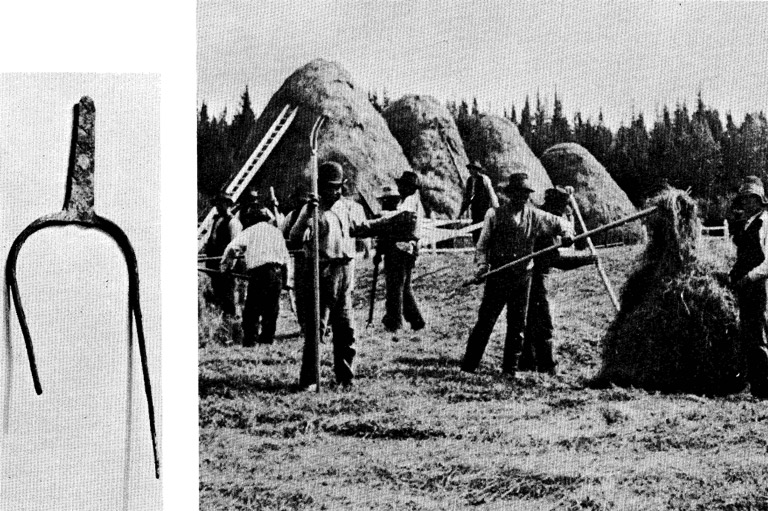

A pitchfork, unearthed at Fort Severn, and a hay-making scene at Rupert's House are reminders of the days when the HBC kept cattle on the shores of Hudson and James Bay.The Beaver Collection

A pitchfork, unearthed at Fort Severn, and a hay-making scene at Rupert's House are reminders of the days when the HBC kept cattle on the shores of Hudson and James Bay.The Beaver Collection -

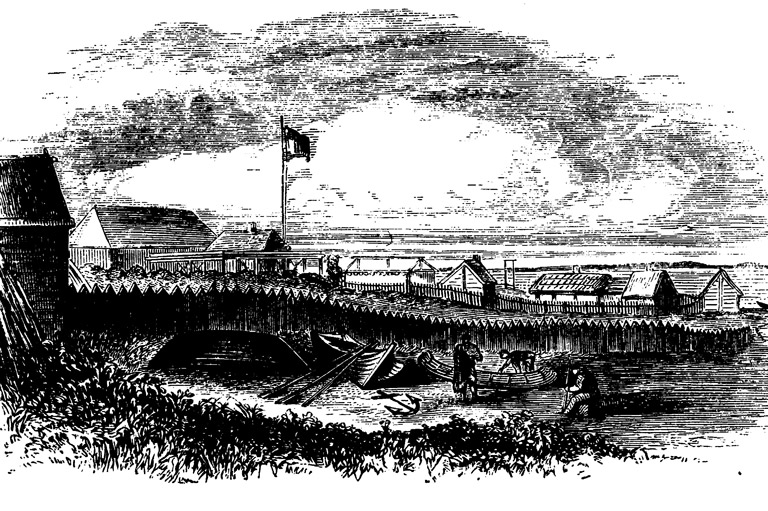

Cumberland House, from a sketch by John Fleming, 1858.

Cumberland House, from a sketch by John Fleming, 1858. -

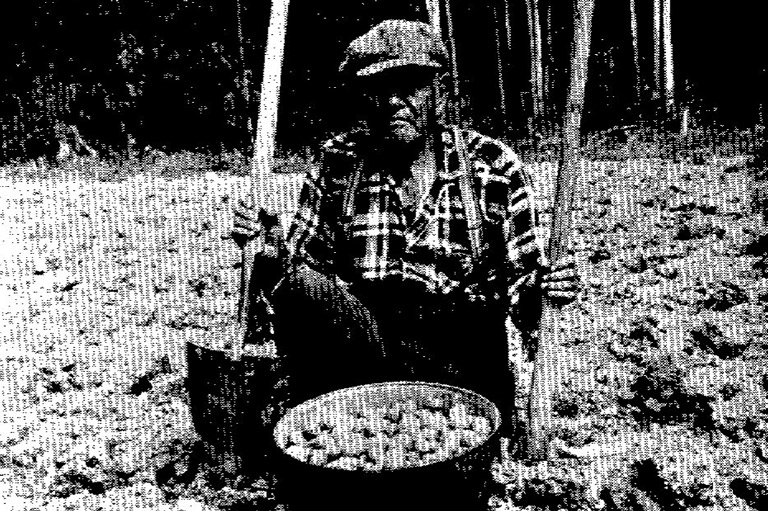

Early Rose potatoes, a variety shipped through the Bay, perhaps a century ago.John Macfie

Early Rose potatoes, a variety shipped through the Bay, perhaps a century ago.John Macfie -

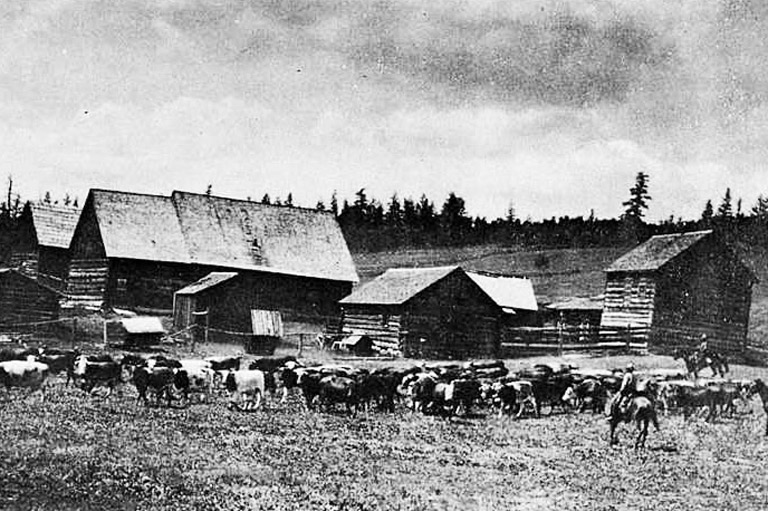

Cattle at Fort St. James.B.C. Archives

Cattle at Fort St. James.B.C. Archives -

McLeod's Lake, 1906.B.C. Archives

McLeod's Lake, 1906.B.C. Archives -

Fort Langley, 1894.B.C. Archives

Fort Langley, 1894.B.C. Archives -

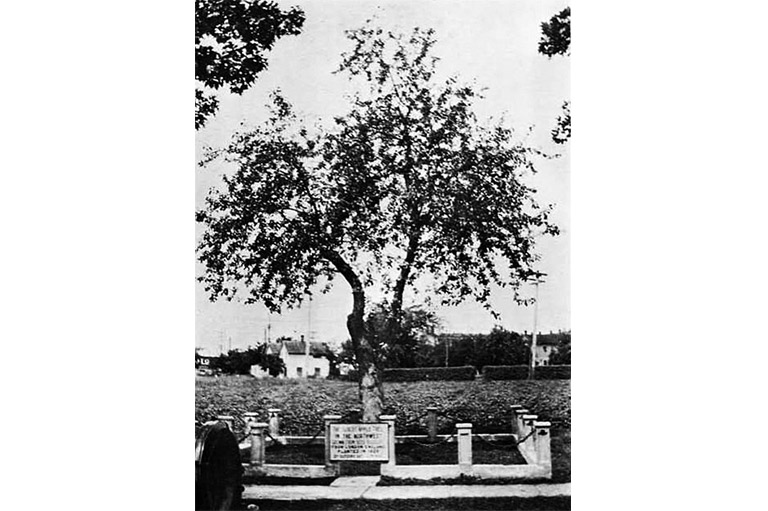

An apple tree said to be planted in 1826 by Dr John McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver from seeds brought from England by A Emilius Simpson.

An apple tree said to be planted in 1826 by Dr John McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver from seeds brought from England by A Emilius Simpson. -

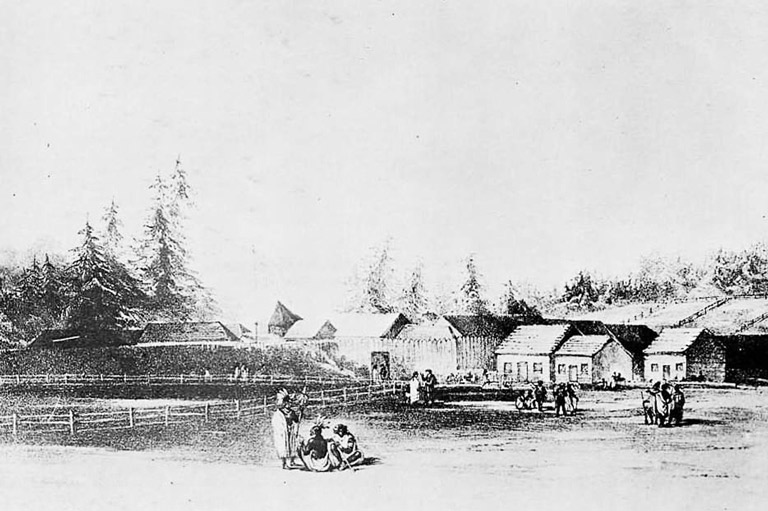

Fort Vancouver 1845, from a drawing by Lieutenant H. J. Warre.

Fort Vancouver 1845, from a drawing by Lieutenant H. J. Warre. -

Drawing of Fort Nisqually.B.C. Archives

Drawing of Fort Nisqually.B.C. Archives

THE BOTTOM OF THE BAY

It was the 9th of November 1668 when Rupert River, at the Bottom of the Bay, set fast with ice. This was in James Bay, the southern extremity of Hudson Bay. Friendly Indigenous people had shown Captain Gillam a sheltered cove where his ship, the Nonsuch, might winter and he had taken his men ashore where they now busied themselves with two essential operations: building a house for themselves and excavating a cellar, twelve feet deep, for their store of beer. They had brought some hens and pigs with them and accommodation had to be arranged for them too.

As soon as the ground could be worked in the following spring, garden beds were prepared and vegetable seeds were sowed, a practice followed throughout the Hudson’s Bay Company’s long history despite many disappointments and difficulties.

There were several reasons for wanting to grow fresh garden produce, the prevention of scurvy being one of the most important, even though locally made spruce beer was just as effective and, they say, not unpalatable if made right. Urgent, too, was a reduction of the heavy expense of sending out enough food from England to last a large number of men a year at least. Again and again the Company’s servants were urged to be diligent in their gardening and to raise what cattle and swine they could, goats too, and horses. One plan was to keep the pigs on Charlton Island in the hope that there they would be safe from wild beasts.

The south end of James Bay is far from being good land for gardens. Larch, spruce, and balsam: poplar, birch, and alder and a sour soil are here in plenty, but that is not the kind of terrain pigs and hens want; they prefer open forests of beech and oak, not to be found much less than five hundred miles to the south. However, the unfortunate beasts struggled along somehow or other and in following summers more garden seeds were sown and, eventually, the produce from them reaped and eaten, as were the hens and pigs for there were not enough volunteers to stay through one winter, keep the place running, and look after the livestock.

In 1681, the Committee in London sent to the Bottom of the Bay: “1 he Goate & 2 she goates & 1 Sow with Pigg wch. we have don in hopes they will increase in the Country & be of use & comfort to our people wch. is a thing that deserves your utmost care as well for the Good of the Factory as for the ease of the Compa. in the buisnesse of Provisions.”

Well, ease and comfort are fine, but there was trouble too. Towards the end of a long report to the Governor and Committee in London in 1682 John Nixon says: “One thing more I must advertise yow that yor. Honours goats are dead, and that it is lost labour to trouble yr. selves to send either them or hogs for they destroy more provisions than they are worth.” Nevertheless, pigs and goats continued to arrive and a great variety of garden seeds, as well as prunes and raisins, to combat the dreaded scurvy. Turnips were a favourite as were peas; radishes, lettuce, mustard, spinach, cabbage, and colewort all did variably well depending on the weather and the industry of the gardeners. This work was assigned to men too sick for heavy duty if there were any such about the fort; otherwise it became a routine task for all hands. Grain could not be ripened, and often peas would form pods and then stop though left on the vine till snow fell.

The spruce beer interested the authorities in London and they asked, politely enough, for a bottle or two of “that Juyce that you tap out of the trees which you mixt with your drink when any one is troubled with the Scurvy.” Meanwhile the Committee continued its efforts to make the people at least partially self-supporting. They pointed out that the latitude of the bottom of James Bay was the same as that of southern England and felt that hedges might be grown to fend off the northwest wind, a system successful in Norway and Sweden.

They sent out books of instruction in gardening, scythes, spades, and other garden tools and more seeds, adding onions and kidney beans to the list. Fresh efforts were made with wheat, barley, and oats. They might succeed and they might not; in any case, said the Committee: “Lett the event be what it will lett it be done”. This might well have been used as the motto of this obscure post, one of Canada’s earliest, but unrecognized, experimental farms.

“One enthusiast put in a requisition for twenty-four spades and twelve shovels... he wrote back, ‘I do assure you it was no mistake... they are not only useful for digging the garden but likewise for clearing the snow out of the yard all winter and other uses.’”

One enthusiast put in a requisition for twenty-four spades and twelve shovels. He got them all right, with a letter of mild surprise at the size of the order. “Oh,” he wrote back, “I do assure you it was no mistake for we had neither spade or shovel in the factory but what was broke in the handle, and they are not only useful for digging the garden but likewise for clearing the snow out of the yard all winter and other uses.”

Farther north, in 1731, Company men had already started on building the great stone fort, Prince of Wales. Shetland sheep and cows had been sent there and throve, but a horse that Richard Norton had brought to help in hauling stone did not do so well. Legend has it that the poor beast on being disembarked stumbled a little along the beach, stopped to survey that desolate landscape, and laid him down to die. In any event, he died as soon as he landed.

Cattle did well and increased rapidly in numbers which was all to the good, except for the fact that hay had to be made for them. At times this became a serious matter and the Moose Fort Journals for 1784 record the sad outcome of one man’s best efforts; year after year he had refrained from killing any of his cattle for beef so that he might build up a strong herd, only to watch them starve to death for lack of the hay he had not been able to grow for them. Churchill, on the other hand, went the other way; one day they killed six pigs and four kids for a real bang-up dinner and on another occasion they killed the bull and ate him too. They explained to London that hay was short and were told that their excuse was an “extream idle Plea.”

One crop has not yet been mentioned. In Churchill, in 1768, William Wales, a visiting astronomer, said that dandelions “made most excellent sallad to our roast geese.” Certain it is that the dandelion does make good greens, and also that it is not native to North America, and one hears again the legend that it was deliberately introduced as a crop by the old Hudson’s Bay men two hundred, nearly three hundred years ago.

There were still other troubles for the weary post keepers. In 1785, at Fort Albany, Edward Jarvis had just finished a letter to John Thomas, Chief at Moose Fort. As he signed his name, a thought struck him and he added a postscript. “We are over run with mice and have a boar cat who can do nothing among them they are so very numerous, would be glad if you could spare a she Cat I would return her or a kitten or two.”

Way up at the north end of the Labrador Peninsula things were no easier but even there, years later, they tried gardens, but a lack of fertile soil produced a hopeless situation, it being impossible as one man pointed out “to convert hard grey rocks into any horticultural purposes.” James McKenzie, who knew the Gulf Shore and the Labrador well, said “one would need to have blood like brandy, the skin of brass and the eyes of glass, not to suffer from the rigours of a Labrador winter.”

It was not all bad. Things got better and better until in 1838 York Factory’s officers’ mess supplied the following. Breakfast was fried fish, except on Sundays when it was beefsteak, with both on Christmas Day. For the evening meal there was always soup, and a meat course which might be beef, partridge, pork, rabbit, venison, grouse, goose, or duck with potatoes; with cheese and tarts for dessert. Wines were served on Sunday only when they had port and madeira. On week days they drank porter or spruce beer.

This was not the usual situation. In most posts the gardens made only an occasional contribution to the officers’ table, and did little to lift the strain on imported provisions. Most meat was secured by the home-guard Indigenous hunters (except the domesticated animals) and the annual goose hunts and fisheries supplied a lot more. Salting and freezing were the only available methods of preservation, except desiccation, and many a post lived from hand to mouth for weeks on end.

THE PRAIRIE POSTS

About a hundred and fifty miles west of the north end of Lake Winnipeg lay Cumberland House. It was built on the Saskatchewan River by Samuel Hearne in 1774, the first HBC post erected in the program of penetration into the Interior. The building of this post was the opening skirmish, though not then recognized as such, in the bitter conflict between the HBC and the North West Company which was to last till 1821, when the two companies united.

Cumberland House lay in the northern coniferous forest, a region not noted for its suitability for agriculture, but gardening got under way very shortly after the post was founded. Matthew Cocking took over in 1775 and in the Journal for 25th October 1776 he notes: “one Man clearing some Ground for Gardening in the Spring”. From then on there are several references to men clearing ground and performing other horticultural tasks but nowhere do we find any account of what success these efforts met with.

The North Westers seem to have had a greener thumb than did the HBC men which is not surprising when we remember that the North Westers came, in the main, from the valley of the St Lawrence and were familiar with farms and gardens.

Four hundred and fifty miles to the northwest of Cumberland House was another post, on the bank of the Athabasca, then known as the Elk River. Here Alexander Mackenzie arrived in 1787 and reported that Peter Pond “had formed as fine a kitchen garden as ever I saw in Canada”. Turnips, carrots, and parsnips grew to a large size, especially the turnips. Potatoes did well, but cabbages failed for want of care.

I measured an onion, 22 inches in circumference; a carrot, 18 inches long, and, at the thick end, 14 inches in circumference; a turnip with its leaves weighed 25 pounds...”

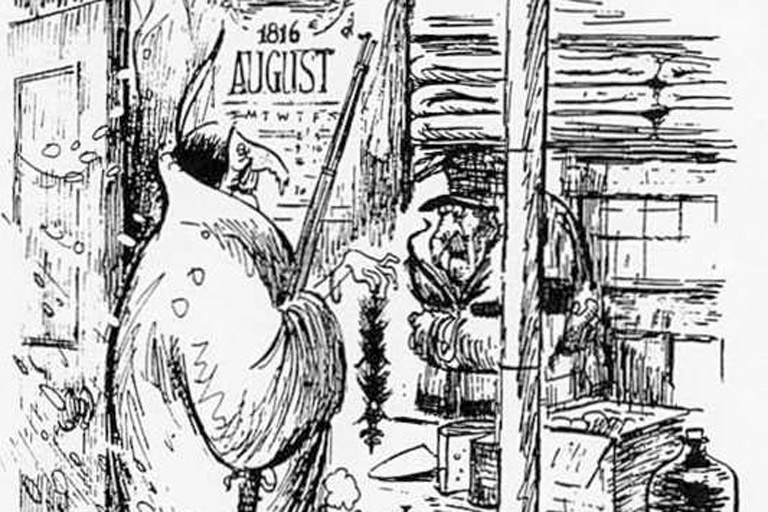

Alexander Henry the Younger, one of the North Westers, found himself in more propitious circumstances. In 1801 he was in the Pembina River post, about sixty-five miles south of Winnipeg, and just across the North Dakota medicine line, the magical boundary between Canada and the States. Here he found a milder climate and a richer soil and gardening became a pleasure instead of a chore, at least by comparison. On the 27th of September 1801, he notes a hard frost which froze his cucumbers and melons; on the 6th of October he dug up one and a half bushels of potatoes and explains that the horses had destroyed his other vegetables. Two years later, however, he was almost jubilant. On October 17th he says “I took my vegetables up—300 large heads of cabbage, 8 bushels of carrots, 16 bushels of onions, 10 bushels of turnips, some beets, parsnips, etc. 20th. I took in my potatoes 420 bushels, the produce of 7 bushels, exclusive of the quantity we have roasted since our arrival, and what the [First Nations] have stolen. I measured an onion, 22 inches in circumference; a carrot, 18 inches long, and, at the thick end, 14 inches in circumference; a turnip with its leaves weighed 25 pounds, and the leaves alone weighed 15 pounds, the common weight is from 9 to 12 pounds without the leaves.” It was only the next year, 1804, Henry took refuge in the peace of his garden and sowed seeds. He seems to have been keen on cucumbers too, and made a nine-gallon keg of pickles, using vinegar from the Manitoba maple sap, which runs less sugar in the sap than does the sugar maple. This year he did well with his potatoes too, having planted 21 bushels and reaped a thousand, “exclusive of what have been eaten and destroyed since my arrival.”

If some of the pawky Scots factors had looked on the post gardens with a jaundiced eye, it was George Simpson who put fire crackers under their kilts. He was appalled at the cost of provisions brought from England clear across the Atlantic, and from Hudson Bay across the prairies and he was confident that a good deal of food could be grown at the posts. When he was at Fort Wedderburn in 1821 he was horrified to discover that the [First Nations inhabitants] were being supported largely by the HBC on imported foods and that they were doing mighty little on their part in the way of bringing in furs. “It has occurred to me,” he said, “that Philanthropy is not the exclusive object of our visits to these Northern Regions, but that to it are coupled interested motives, and that Beaver is the grand bone of contention.”

There were times of destitution and even of actual starvation in some of the prairie posts. In 1855, Peter S. Ogden’s son visited the Peace River forts in search of leather. “The district was in a starving state,” he reported, “people being obliged to eat dogs and horses which had died from bad treatment. . . . When I reached Dunvegan there was not an ounce of provisions in the fort, and my men were obliged to go to bed supperless. Our sinews for the district were all eaten by the Dunvegan men previous to my reaching there.”

Simpson felt, too, that more horses could be used, in such works, for instance, as improving portages and carrying freight and so he proposed to raise more of them on the spot. He wrote to Francis Heron at Edmonton requesting him to procure twenty breeding mares and ten entire horses as early as possible. A restrained footnote points out that “the proportion of stallions to brood mares is absurd, judging by ordinary standards.” No comment from the horses.

Wherever he went, Simpson sized up the agricultural possibilities and urged the men at the various posts to take advantage of the opportunities that presented themselves. It all sounded fine but there were very real difficulties to be met. No matter how you fenced your garden the deer got in and ate everything before it was even near maturity, and then the [First Nations people] came along, camped just outside the post and used your fence rails for firewood, perfectly innocently and with no thought of doing wrong. What is wood for but to be burnt?

NEW CALEDONIA

It took the traders but a single generation to cross the prairies and the mountains. Fort McLeod (now McLeod Lake, B.C.) was opened in 1805, and the surge westwards did not stop there, for Stuart’s Lake (later Fort St James) came in 1806 and half a dozen other posts followed in quick succession. New Caledonia, as the district west of the Rockies came to be called, was a new and rich area in the fur lands. By and large the fur-bearers are forest animals and New Caledonia finds itself in the sub-alpine forest zone, an excellent habitat for them but not for kitchen gardens. Except for patches along the banks of rivers and lakes, there is little fertile soil; the winters are long and very cold, the summers too short to ripen any but the earliest vegetables. Nevertheless, gardens were established at every post and with a surprising degree of success.

Much of this success was due to the enthusiastic encouragement of such men as Peter Skene Ogden who fully agreed with Governor George Simpson that the posts could be made much more nearly self-sustaining than they had been, and never failed to observe and comment on the success the various post masters had encountered. John Tod had charge of Fort McLeod in 1824 and had this to say about his gardens: “Poor success, I may add here, attended my farming experiment at Fort McLeod, which is in about 55 degrees north latitude, and close to the Rocky Mountains. At Stuart’s Lake, about 100 miles south, and more westerly, potatoes ripened on the slopes, but in the hollows, or near the lake, were liable to frost bite. In the same direction, and about 40 miles more southerly, near latitude 45 degrees, at Fraser’s Lake, some barley and potatoes grow for use. I saw patches of wheat that promised to ripen at Fort George, 80 or 90 miles to the east of Fraser Lake, and in the above named latitude. These results of small experiments in New Caledonia indicate that the ordinary cereals and vegetables might be produced by skilful and careful agriculture.”

“George Simpson, the Governon, was not well impressed. :The Soil,” he write, “is by no means exuberant...”

George Simpson, the Governor, was not well impressed. “The Soil,” he wrote, “is by no means exuberant, being generally of an indifferent Mould of about 8 inches from its surface—a bed of gravel and sand succeeding alternately. Esculent vegetables, notwithstanding every precaution to preserve and bring them to perfection have nearly altogether failed—and the last crop of Potatoes did not yield the produce of one fourth of the Seed put in the ground.”

In Fort Alexandria, a hundred and thirty miles due south of McLeod Lake and in the warm and sunny Dry Belt, things were a bit better. This fort was built by the North Westers in 1821, a few weeks after the union of the two Companies, an event of which they were blissfully ignorant till somewhat later. Here, at last, was a place in the interior of British Columbia where wheat could be grown. Between 1843 and 1848 from 400 to 500 bushels of wheat were ground into flour, using horsepower to turn the eighteen-inch mill stones.

George Simpson, but little affected by the woes of others, admitted when he visited New Caledonia in 1828 that: “In regard to the means of living, McLeod’s Lake is the most wretched place in the Indian Country: it possesses few or no resources within itself, depending almost entirely on a few dried Salmon taken across from Stuarts Lake, and when the Fishery there fails, or when any thing else occurs to prevent this supply being furnished, the situation of the Post is cheerless indeed. Its complement of people, is a Clerk and two Men whom we found starving, having had nothing to eat for several Weeks but Berries, and whose countenances were so pale and emaciated that it was with difficulty I recognised them”.

Full of sympathy, but unable to do much about it, he continued his travels to Fort St. James where he found that “a few White Fish in the Winter with an occasional treat of Berry Cake prepared by the Natives, and a Dog Feast on high days and holydays constitute the living of nearly all the Posts in New Caledonia: and altho’ bad as to quality, would not afford grounds for complaint, if the quantity was sufficient to satisfy the cravings of Nature: but the people are frequently reduced to half allowance, to quarter allowance, and sometimes to no allowance at all.” The dogs were purchased from [First Nations people], who did not eat them though the men at the forts relished them.

Continuous effort, often frustrated by the poorest of rewards, eventually brought about some improvement. In 1833, John McLean arrived at Stuart’s Lake. He commented on the menu as “scarcely fit for dogs” and then goes on to say that “a few cattle were introduced in 1830, and we now begin to derive some benefit from the produce of our dairy. Our gardens (a term applied in this country to any piece of ground under cultivation) in former times yielded potatoes: nothing would grow now save turnips. A few carrots and cabbages were this year raised on a new piece of ground, which added to the luxuries of our table”.

That was just another of the frustrations; the soil was poor, its minerals quickly exhausted and no fertilizer to be had. A few crops could be harvested and then new land had to be broken, and there was precious little of it. Altogether the posts at the east end of the great belt of northern forests, around the Bottom of the Bay, and those near the west end, in New Caledonia, were about the poorest possible bets as regions suitable for gardens or larger agricultural operations.

THE PACIFIC COAST

All the posts we have discussed so far, those at the Bottom of the Bay, the Prairies, and New Caledonia, were (with the exception of some of the more southerly prairie posts) in the North Woods, the habitat preferred by most of the fur-bearers. These posts obtained much of their supplies through Hudson Bay after hundreds, sometimes thousands, of miles of river transport, hard on men and hard on the expense account, and they followed the customs and procedures laid down in the Company’s early formative years. There was a traditional way of doing everything laid down in the Standing Rules & Regulations and changes came slowly indeed, usually in the face of determined opposition.

Back in the Old Country there had been changes. Steam-driven machinery had brought about the Industrial Revolution and altered the whole pattern of industry and, indeed, of thought. It was during this period that the establishment of agricultural posts on the Pacific coast and the scheme to locate people in the Red River Settlement, where Winnipeg stands today, were undertaken. Fort Vancouver and the other farms, satellite to it, experienced the transition from the old ways to the new, barely perceptible at first but becoming more and more obvious as American settlers drove their covered wagons into the Oregon Country.

It was the cross-country expedition of Lewis and Clark that convinced John Jacob Astor that there was fur to be trapped and money to be made on the Pacific Coast and in 1811 he founded Fort Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia River. Many difficulties confronted him, not the least of them caused by the War of 1812, and in 1813 he was glad to sell out to the North Westers, who continued operations until their union with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821.

To say that he [George Simpson] was horrified is to put it mildly, even allowing for the fact that an assumption of horror was one of his familiar poses.”

On the 8th of November three years later, Governor George Simpson visited Fort George, as Astoria had been renamed. To say that he was horrified is to put it mildly, even allowing for the fact that an assumption of horror was one of his familiar poses. True enough, the situation there was wild in many ways. The people were living on the most expensive imported European provisions in a country where agriculture was easy and rewarding; they had made little or no effort to extend their own activities in trapping, or those of the natives, and a blind adherence to tradition had filled the warehouses with completely useless and quite unsalable goods, including ostrich plumes, beloved of the First Nations back east, and coats of mail, beloved of nobody.

Never content with half measures, Simpson determined to move. The North Westers had complained that Fort George was damp and that the furs were spoiled in consequence and the climate was not a healthy one for the men. They, too, had thought of a move, but never actually undertook it. Perhaps the most serious objection to the Fort George site in Simpson’s eyes was the fact that there was not nearly enough room for the large agricultural enterprise he had in mind. At Fort George there was but little land suitable for the plough, most of the rest of it being rocky and uneven, and there were stands of heavy timber that would have to be cleared if farming operations were to expand. And, worst of all perhaps, it was on the south side of the river and might well find itself in United States territory if the Columbia River should be chosen as part of the international boundary.

A few days after his arrival in November, Simpson sent a party upstream to look for a better site. The first attempt, in a leaky boat, got nowhere; the next was more successful, but they found nothing suitable till they had passed the mouth of the Willamette and were some hundred miles from the coast. Here they found a flat stretch overlooking the river; it had been named La Jolie Prairie and terminated in a lookout which Lieutenant Broughton had named Belle Vue Point as early as 1792. Here were extensive bench lands high enough above the river to avoid flooding and wide enough to provide all the acreage they could ever need. Moreover the benches needed little clearing before being laid under the plough. So, late in 1824, a work party set out to build the new fort and, by the spring of 1825, they had a living house for the gentlemen, two storehouses, a room for First Nations, and temporary quarters for the men ready for use.

From its beginning to its end in I860 the new post, “baptised” Fort Vancouver by George Simpson on 19 March 1825, had a success that is hard to overestimate. It was many years before any other farm in the Oregon Country could compare with it; in fact, it is quite possible that its performance never has been equalled for returns from such an establishment. In the course of time, satellite farms were established and they too repaid many times over the work expended on them. The importation of provisions from England for the far west was brought to an end. Meat, grain, fruit, and vegetables were grown in abundance, and foodstuffs were exported to Russian America, to California, and to Hawaii. Simpson had been proved abundantly right, and he never let them forget it. Water power on Mill Creek, six miles up the river, was harnessed for saw mills and grist mills, a school was established, a hospital, and a chapel. Fort Vancouver was the biggest and most important place in the Oregon Country. As headquarters of the Columbia District its influence extended from San Francisco Bay to New Caledonia and Hawaii.

The driving force behind the Columbia District as a whole and its nucleus, Fort Vancouver, was Dr. John McLoughlin of Rivèire-du-Loup. He had been apprenticed to a physician in Quebec when he was about fourteen and five years later got his licence to practice medicine, surgery, and pharmacy. He joined the North West Company in 1803 and, after the Union, became a Chief Factor and was assigned to the Columbia District in 1824. So much has already been written of this extraordinary man that it is surely not necessary to enter into further details. Not only had he established the first school, but also the first circulating library, the first theatre, and one of the first churches. Here at Fort Vancouver one could buy supplies and here, too, settlers could be advised in their choice of land and, later, sell their produce. It is difficult to believe that such an establishment could have so short a life, from 1825 to I860. About 1865 a visitor to the site found no sign of it but a pile of mouldering hay.

Two names are associated with McLoughlin’s: James (later Sir James) Douglas and James Murray Yale, both to achieve fame as the pioneers of agriculture and settlement in what is now British Columbia. Yale, well-regarded by Simpson, was eventually put in charge of Fort Langley on the south bank of the Fraser River, some eighteen miles east of the present city of New Westminster. Here Yale established a farm that at one time rivalled and indeed surpassed Fort Vancouver, for as that fort declined, Fort Langley was still in the ascendant.

Yale’s attitude towards McLoughlin was one of devotion, almost of hero-worship. He had spent months at Fort Vancouver nursing a wounded hand and had had the opportunity of observing all that went on. When he was given Fort Langley he was able to put to practical use all that he had learnt. Indeed, he went further and embarked on enterprises that had not been attempted on the Columbia. He shipped $ 10,000 worth of cranberries from the nearby bogs in one season, shipped salt salmon down the coast and over to Hawaii, grew hemp which he exported to England, sold barrels made by his cooper for the salmon and cranberries, made brooms, axe handles, toboggans, horse collars. He grew thousands of bushels of wheat which he ground into flour in his own mill, shipped many thousands of board feet of lumber abroad, grew foodstuffs for Russian America, and, with all this, supervised the activities of his many employees and Indigenous traders. Then, too, he had unfriendly Indigenous people to contend with. On one occasion, an Indigenous man got clear away after murdering a man near the Fort. Months later Yale was told that this same man was coming down the river in a canoe with some others. Yale, calm and quiet, took his rifle, went down to the waterfront, shot the murderer through the head as the canoe went by, returned to the Big House, hung up his rifle without a word, and went on about his business.

Yale left Fort Langley in 1859 after thirty-one years there, twenty-five of them in charge, during which time he introduced agriculture to the southwestern mainland of British Columbia with the greatest success. The farm continued its operations on a much reduced scale until June 1896 and was eventually subdivided and sold. Yale’s list of “firsts” is long indeed and the year’s furlough he was granted was well deserved.

As early as 1832 Dr McLoughlin had thought of forming an independent company to handle agricultural affairs in the Oregon Country. There had been complaints that fur should be the sole concern of a fur-trading company, though Simpson had stated his opinion that anything that made money for the Company was worth pursuing. In 1839, when the Company signed an agreement with the Russian American Company to supply them with foodstuffs, the Puget’s Sound Agricultural Company was formed, legally quite separate from the Hudson’s Bay Company but actually a subsidiary with control firmly in the hands of the Governor and Committee. Dr William Fraser Tolmie was put in charge with headquarters at Fort Nisqually under the supervision of Dr McLoughlin. There was plenty to do. Nisqually and Cowlitz farms were large and productive and others were added as time went on. Fort Langley was not included, as Yale was obviously more than capable of looking after that.

In the Victoria area on Vancouver Island, four farms were established under the Puget’s Sound Agricultural Company: Macaulay Point, 1849; Langford, 1851; Viewfield and Craigflower, 1853. Only Craigflower Manor still stands to remind us of those days when thousands of sheep grazed in the pastures about Victoria, including today’s fashionable Uplands.

The adoption of the 49th parallel as the United States-Canada Boundary put Fort Vancouver definitely far below. Headquarters of the western department was transferred to Fort Victoria in 1849 and it became necessary gradually to close Fort Vancouver. All the equipment for the mills, all the workshop tools, all the goods in the warehouses, everything movable was loaded on board the steamer Otter, and transported to Victoria. It took three trips in all. On the 14th of June I860 the last piece of freight was loaded, the officer in charge, Chief Trader Grahame, turned over a large bunch of keys to the U.S. authorities, and in half an hour he sailed away, ending a highly successful and important venture in agriculture.

Though the Fort was abandoned, the Company still claimed its lands in the Oregon Country, and presented the U.S. government with a bill for a million dollars; they did not expect to get it, for Governor Simpson had been tipped off that if he could get $300,000 he was to close the deal. Eventually he got $450,000 for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s interests and $200,000 for the claims of the Puget’s Sound Agricultural Company—in gold!

RED RIVER SETTLEMENT

While the Oregon Country was seeing this most successful experiment in agriculture, a similar venture, but far less successful was being carried out on the eastern prairies where the Red River is joined by the Assiniboine, the present site of Winnipeg.

It was Thomas Douglas, fifth Earl of Selkirk, who was the moving spirit behind an attempt to form here a settlement of dispossessed Scottish crofters who had been turned off the lands they had occupied for centuries as a result of changes in the legislation governing rents and land management.

The soil of the Red River Settlement was certainly suitable for agriculture though perhaps not so rich as that of Fort Vancouver; the climate was decidedly less hospitable, and the settlers were plagued by weeds, grasshoppers (which did enormous damage), floods (also most destructive), ravaging flocks of birds and, above all, inexperience and a lack of competent leadership.

Though the grant of land extended over 116,000 square miles, the actual settlement was confined to the west bank of the Red River. The arable land was divided into lots an eighth of a mile wide and over a mile in depth, extending back to a road. Behind the road was a hay meadow common to all and beyond that the limitless prairie stretching out to the west. On the cast side of the river there was timber, free for all. It was not long before log cabins were built on most of the lots, but all was not as rosy as it appeared.

Not only were the Scottish settlers more familiar with sheep than with gardens, but they sadly lacked tools and even the means to make them. Moreover they were not welcome and they were not allowed to forget it. “Every Gentleman in the Service both Hudson’s Bay and North-West was unfriendly to the Colony,” wrote Simpson to Colvile in 1822. Both Companies were principally interested in furs and were averse to seeing the country fenced and farmed. The hope that the little settlement could supply the Hudson’s Bay Company with the produce of their land was doomed to disappointment. Indeed, in 1820 they had even consumed their seed wheat and had to send a party on snowshoes five hundred miles to Prairie du Chien to buy American wheat.

Realizing the situation, the Company after the Union in 1821, initiated a number of schemes intended in part at least to give the settlers work. Large sums were spent in organizing such ventures as a Buffalo Wool Company, which failed because the cloth woven from this wool could not be sold in England for a fraction of what it cost to manufacture it in Red River. Then they tried a Tallow Company, which failed, and another company was to grow flax and hemp. This, too, came to nothing.

Governor George Simpson was annoyed. He hated incompetence and, in writing to Andrew Colvile, said: “Mr. Pritchard and his Buffalo Wool concern make a great noise: he is a wild visionary speculative creature without a particle of solidity and but a moderate share of judgement: if the business was properly managed I have not a doubt of its turning out well.”.

Another venture in which Mr. Pritchard, who was Lord Selkirk’s agent, was concerned was the “Hayfield Experimental Farm” which was established before the Union; it collapsed in 1822 because of foolish and extravagant mismanagement, nor was it the only experimental farm to fail. By 1824 the settlers had managed to secure or make some primitive implements, such as ploughs, and sickles with which the grain crops were harvested. They were threshed with a flail and ground in stone querns turned by hand, later by horses, and in 1825 the first windmill was erected. Another fine idea was distilling barley to reduce the cost of importing rum. There were a number of the settlers who were familiar with the process. Then in 1826, came the great flood, a “complete extinguisher”: but, strangely enough, it proved an ill wind that blew much good, for the ruin was so great that many of the less desirable settlers left the place: those who remained to build anew had reached the turning point in their fortunes. Five years later the Red River Settlement was on its way to prosperity. Each settler had a comfortable home with barns and outhouses full of grain and cattle. Moreover, unlike the old days in Scotland, it was all their own and there were no landlords to hound them, and no tithes or dues payable to either church or state.

It was about this time that they had another go at an experimental farm. There had been two or three after the first fiasco and now, in 1831, Mr A. R. Lillie, who had had a good deal of experience in managing a farm in Fifeshire, was charged by the Governor to see what he could do. He worked at this for a number of years with a success that nobody had foreseen, and the amount of grain he produced was a significant proportion of the total Canadian wheat crop.

“Another disastrous venture was in raising sheep...[On the 2nd of May 1833] they started with 1,300 sheep and lambs, ... but got back on the 12th of September with a little over 200 sheep.”

Another disastrous venture was in raising sheep. In the winter of 1832 a party was sent south into the United States to buy a suitable flock of sheep and, after a wrangle about prices, was obliged to go even farther south to Kentucky. Then came the task of driving the sheep back, some 1,000 miles or more. They started with 1,300 sheep and lambs, but what with festering wounds caused by spear-grass, lameness, rattlesnakes, and the necessity of keeping the herders fed on the trail, the flock was sadly depleted. They left on the 2nd of May 1833, and got back on the 12th of September with a little over 200 sheep; these apparently recovered from their long walk and were later reported to be doing well.

Farming was the important activity, but there were flower gardens too, though there is but little mention of them in the first few years of the settlement. In 1868, when the success of Selkirk’s experiment was beyond doubt, there was a big garden at Lower Fort Garry in charge of an old English gardener who sent to the Old Country for all his seeds. Fresh flowers and vegetables graced the officers’ table from the first asparagus in the spring to the last frozen turnip and parsnip well into winter, and the Lord help anybody the gardener saw touching anything without his express permission.

By 1878 Red River Settlement had a population of nearly 6,000 with model farms equipped with the most modern machinery and “Mr. Inkster tells me that last year from seven bushels of potatoes planted he dug two hundred”.

Truly, Labor omnia vincit.

THE PRAIRIE FARMLANDS

Under the terms of the Deed of Surrender, sealed on the 19th of November 1869 the Hudson’s Bay Company surrendered to the Queen’s Most Gracious Majesty all the rights and privileges granted by King Charles II in 1670. In return the Company received £300,000 sterling, and the right to claim (at any time during the next fifty years) a grant of land in any township or district within the Fertile Belt, not exceeding one-twentieth of such township or district. The Company also retained its posts and other establishments and a reasonable area of land surrounding them, amounting to about 45,000 acres.

Selecting one-twentieth of an unsurveyed area presents difficulties and it was not until the Dominion survey of the prairies was begun that a fair allocation could be made. Grants of lands allocated were made progressively as the survey of each township was approved, and the HBC paid its ratable share of the survey cost. The Fertile Belt was bounded on the south by the United States; on the west by the Rocky Mountains; on the east by Lake Winnipeg and Lake of the Woods; and the northern branch of the Saskatchewan River formed the northern boundary, an area of about 140 million acres, of which one-twentieth amounted to 7 million acres. It was determined that in every fifth township Sections 8 and 26, and in every other township Section 8 and the south half and northwest quarter of Section 26 should be known as Hudson’s Bay Land.

It was actually as late as 1928 before all the final details were settled, but as early as July 1872 the first land sale was made of a Winnipeg town lot to the Canadian Pacific Hotel Company. Town lots were put on the market early because the area was already surveyed and could therefore be defined in the title deed. The selling of farm land began in August 1879, when William McKechnie bought a whole section of 640 acres near Emerson, Manitoba. It was listed on the books as Sale No. 1: Section 8, Township 1, Range 3, east of the Principal Meridian. It cost him $6.00 per acre, or a total of $3,840.

Land sales were slow all through the 1890s but rose to a peak of nearly 370,000 acres in 1903. The First World War brought another marked decline and the Company decided to do something about it. In cooperation with the Cunard Steamship Line they organized a company with the somewhat unwieldy title of “The Hudson’s Bay Company Overseas Settlement Limited.” They had a London office at No. 1 Charing Cross and an office in Winnipeg.

Settlers were given every imaginable assistance in selecting land (not necessarily HBC land), they were advised and instructed in farming methods, helped in arranging tickets and transportation, even assisted financially in some cases. The Company established a training farm in England under the supervision of an experienced Canadian farmer. Here young men were taught milking, ploughing, haying, and all the other skills needed by a competent farmer. Advertisements were run in The Beaver and in other media urging Canadian farmers who needed help to get in touch with the Company who would come to their assistance in getting suitable young men, and also their families and friends if need be, to come out to Canada and settle on the land, first as hired help and then, if all went well, on their own.

HBC lands were for sale at the following rates: one-eighth cash, balance in seven equal annual payments with interest payable annually at seven per cent; all minerals reserved. During all these years since the Deed of Surrender the Company paid taxes on its nearly seven million acres, or what was left of them. In June 1927 it was estimated that these tax payments amounted to 15,000,000 dollars and, some years later, when the Dirty Thirties struck, it was the Company’s taxes that saved many a tight situation. By 1923 there were about three million acres still unsold as well as a great deal of town property. By 1960 all the farm land had been sold.

And so the land where once the buffalo roamed became the bread basket of Canada, a land of prosperity, of farms, towns and villages, churches and theatres, roads and railways, and from the first fumbling efforts at the Bottom of the Bay it was the Hudson’s Bay Company’s persistent and unremitting efforts that pointed the way to development of agriculture in the Canadian West.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement