Living in Harmony

When I was a girl, my grandmother Ida Culley was a model for me of a beautiful, self-confident woman, an equal partner in her marriage and in her working life. She was a pianist who played onstage and on the radio in a two-pianos, four-hands act with my grandfather, Harry Culley.

When my cousin Barbara Culley and I visited her, we’d sit at her vanity table’s three-way mirror, spraying ourselves with her perfume, spreading her Italian balm over our faces, and gluing on her false eyelashes, all the while imagining ourselves in her glamorous life. She’d show us her leather-bound album with pictures from their voyage to South Africa in 1937, and we’d marvel at the monkeys, lions, and snakes they encountered while touring there.

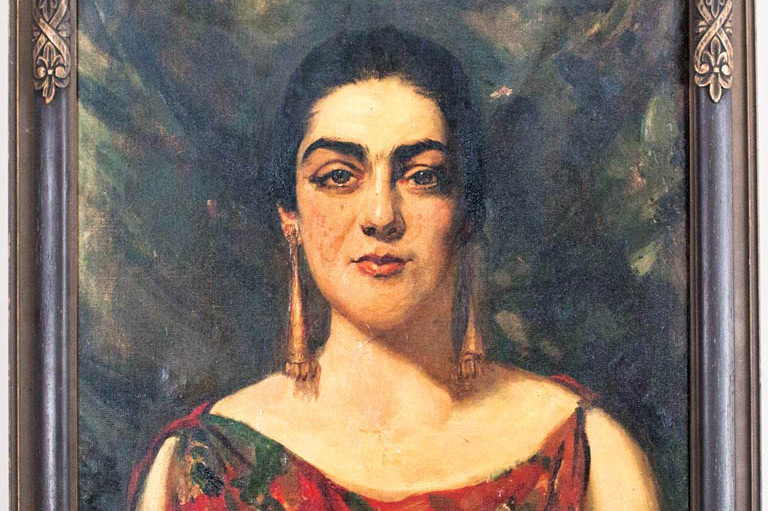

Then we’d beg her to bring out her old trunk from the hall closet, stamped with labels from around the world, so that we could see her elegant gowns designed by the British fashion legend Sir Norman Hartnell. “He was the designer for the Queen, you know,” she would say. Donning the dresses, we would strut around, imagining her walking onto the stage from one side and Harry from the other, meeting in the middle to sit down at their grand pianos. She’d be wearing an over-the-shoulder gown, with her wavy blond hair and pencil-thin eyebrows.

We’d ask her to play songs such as “Tenderly,” “The Man I Love,” and “Stardust.” Her hands flying over the keys, she’d look over at us, smiling, and ask what we’d like to hear next. When asked about her talent at the piano, she’d say that she had nothing to do with it, that it had “come from God,” which was surprising, as otherwise she wasn’t religious. I always wondered what had led up to her remarkable career. It wasn’t until after her death in 1983 that I pieced together her life and that of my grandfather through the newspaper clippings, programs, and publicity photos I found.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Born in Toronto in 1897, Ida Fernley was a child prodigy. On June 5, 1901 — Pretoria Day — she attended a parade with her mother on Yonge Street to celebrate the end of the Boer War. The marching band played “Soldiers of the King,” and four-year-old Ida was so impressed by the song that she went home and played it perfectly, by ear, on the piano.

She then went on to demonstrate pianos in the showrooms of large musical instrument companies such as R.S. Williams & Sons, where a promotional brochure from March 17, 1905, stated: “By special request we have engaged Miss Ida Fernley (age 7 years), the wonderful child pianist. This little lady fairly captured her audience when she appeared at our warerooms last month. Since then we have been besieged with requests to have her appear again. This we have decided to do, and are glad to inform our friends that Miss Fernley will be here on Saturday afternoon.… We invite you to come and see the most wonderful child pianist ever heard in Canada.”

In class she played for the children coming in from recess, and after leaving school in grade eight she performed at the Clinton Street, so called because it charged a nickel for admission. Her piano music accompanied popular movies starring another Canadian, Mary Pickford, as well as those of comedians Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Lloyd’s love interest, Bebe Daniels, among many other films. She later said she “faked it” — playing dramatic music with minor chords for the tense scenes and sentimental, romantic melodies for the love scenes — an early style of jazz improvisation.

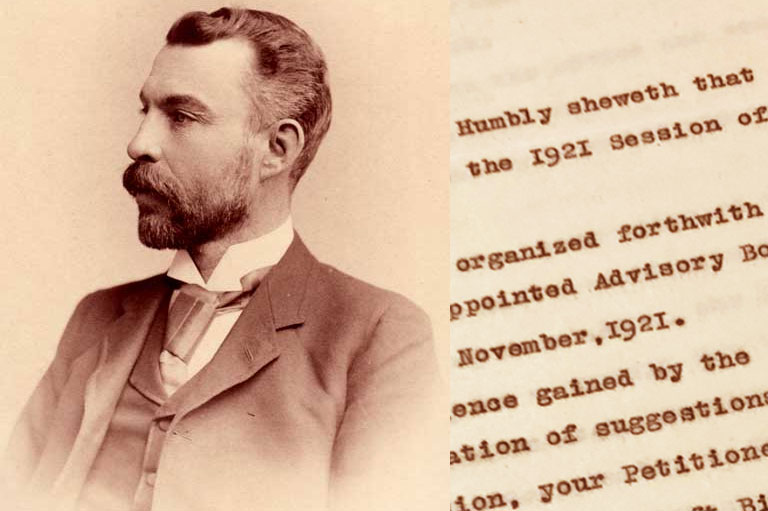

That’s where she met Harry Culley, who was also playing piano for silent movies in a theatre across the street. Born in 1895, Harry came from a family of musicians. His father, Teck Culley, was the principal flautist with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and its predecessors — including the Grand Opera House orchestra and the Toronto Conservatory Symphony Orchestra — from about 1890 to 1935. Teck Culley taught at the Toronto Conservatory of Music (later renamed the Royal Conservatory of Music) for thirty years and was a charter member of the American Federation of Musicians.

Harry Culley was classically trained, having taken piano lessons both from his maternal grandmother and at the Toronto Conservatory. Like Ida, Harry also left school after grade eight to become a full-time musician.

Harry Culley and Ida Fernley married when she was sixteen and he was eighteen, after she became pregnant. They were so young that, after visiting Toronto City Hall for the wedding ceremony, they went back to their respective parents’ homes. By the time Harry Jr. was born in 1914, they had saved enough money to move to an apartment on Grange Avenue. The pair joined forces not only personally but professionally.

From 1920 to 1922, they ran a music store where they sold pianos, Victrolas, and sheet music, and where customers could listen to seventy-eight-rpm records in a specially designed booth. Ida looked after the store and demonstrated the pianos, playing the latest sheet music while looking after Harry Jr. and baby Ross, born in 1922. Harry Sr. worked full-time as a musician. From 1929 to 1930 he conducted the Royal York Hotel orchestra and made other appearances, such as at the Columbus Hall in 1934, where he and his orchestra were described as “Masters of Rhythm,” playing dance music from 9:00 p.m. to 2:00 a.m.

Once their sons were a little older, in the early 1930s, they promoted their talents as a duo, playing on two pianos with four hands on Toronto radio stations CKCL, CKNC, and CFRB. The two-pianos, four-hands genre originated in the late 1700s but grew in popularity in the 1930s and is still practised today. For pieces that didn’t have two parts, Harry wrote out the arrangements for the second piano by hand, a labour-intensive process.

The couple specialized in modern piano novelties — short, quick instrumental pieces that had classical and popular influences, such as the “Four Aces Suite” by English composer Billy Mayerl and “Coaxing the Piano” by American composer Zez Confrey. These compositions were often written to show off the performers’ prowess. Other music in their repertoire included George Gershwin’s 1924 composition “Rhapsody in Blue,” Duke Ellington’s 1935 jazz song “In a Sentimental Mood,” and Ellington’s 1938 ballad “Prelude to a Kiss.” Music publishers often sent them free promotional copies, hoping they would play the songs on air so that people at home would buy the sheet music to try out on their own pianos, or purchase the records to play on their Victrolas.

Described by one reviewer as “Toronto’s premier two-piano artists,” the pair were known as either the Black and White Spotters or the Hot Spots, depending on which radio station employed them. Ida Culley adopted the single name of Claudette to add appeal to their act, inspired by her heroine, the beautiful, talented Hollywood actress Claudette Colbert. She always dressed up, even though she was playing for radio and the audience couldn’t see her. They rehearsed at least four hours for their fifteen-minute shows.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the audience for radio shows grew, since tuning in allowed listeners to enjoy free entertainment at a time when many couldn’t afford to go out. The stations sold air time to advertisers such as tobacco companies to pay for the shows. The chatty “Tuning in with Jim Hunter” column in the Toronto Telegram would often share news about the pair’s appearances. “For consistently fine work, the two-piano team of Claudette and Harry Culley are hard to beat,” one of Hunter’s columns said. “Possibly there isn’t another local program as well rehearsed as this one.”

Another newspaper review that appeared around 1934, headed “Top-Notchers of Canadian Programs,” raved: “I want to call your attention once more to CKCL’s Hotspot Review at 6 every night. My wife and family now know better than to start calling ‘Hurry up poppa, or your dinner’ll get cold.’ They know I listen to the Hotspotters before I eat dinner every night…. This isn’t a plug. I don’t smoke Golden Virginia tobacco, and don’t want to, but I take my hat off to those fellows for paying whatever dough it costs to produce a program of this calibre in this town which spends less on and expects more from radio than any burg in the world... Orchids to you — Hotspotters!”

Advertisement

By 1936, the duo had built up a following on the radio and at theatre performances. But as the unemployment rate in the city continued to rise to seventeen per cent, the Culleys’ radio show sponsors terminated their endorsement contracts due to declining product sales, and the shows were cancelled one by one. Finally, with no work, they ended up walking away from the house they’d bought on Winnett Avenue in Toronto. Like so many others at that time, they were down on their luck.

At one of their final concerts, at Shea’s Hippodrome, they were spotted by British theatrical agent Jack Hylton, who was touring around the United States and Canada searching for talent. He invited the pair to London, England, where the music-hall scene was still going strong and the British audiences were eating up the kind of new American music that the Hot Spotters were playing. They took him up on his offer, leaving their two sons, Harry Jr., aged twenty-two, and Ross, aged fourteen, to live with Harry Sr.’s parents.

In London, Harry and Ida Culley performed on the venerable BBC and the upstart Radio Luxembourg, a commercial station that was challenging the public broadcaster’s near monopoly of the airwaves. They worked with Canadian Raymond Massey on his 1937 production of the drama The Orchard Walls by Merton Hodge at St. James’s Theatre. They teamed up with Bebe Daniels — the former Hollywood star whose silent movies they had once accompanied at the nickelodeons — and with Bebe’s husband, Ben Lyon, who had developed a comedy-and-song act. With them, the piano duo hit the road to tour the theatres and seaside pavilions of England, Wales, and Scotland.

Harry Culley often wrote back to the “Tuning in with Jim Hunter” column to keep their names alive on the Toronto scene. In one missive he said: “They certainly like our playing over here. We are on the Paramount Astoria theatres circuit, playing at the most beautiful theatres in London. We will be on the British Broadcasting Corporation next week but they don’t run the radio stations here the way they do in Toronto. We made recordings with Dubois Somers orchestra [at Radio Luxembourg] three mornings last week and pocketed $100 for our work. These recordings will be shipped to a station on the continent for commercial programs. Jack Hylton is our personal manager and, believe me you, he gets us plenty of work.”

They played in the British Isles steadily over a couple of years. They were there during the abdication of King Edward VIII in December 1936, and the following spring, on May 9, 1937, they performed at a concert at London’s Phoenix Theatre in celebration of the upcoming coronation of King George VI. On September 10, 1937, Harry and Ida embarked on a three-and-a-half-month tour of South Africa with Bebe Daniels and Ben Lyon. During their two-week voyage from England to Africa on the RMMV Stirling Castle, they performed nightly in the First Saloon Lounge. The program described them as “Popular Canadian Radio Stars.”

In South Africa, their engagements took them to cities as far as 1,600 kilometres apart. Ida wrote, “Our special car would usually set out about 2 a.m. Sunday morning and arrive at our next spot around noon the following Monday.” While travelling, they saw lions lying by the side of the road, black poison dripping from cobra fangs, and wild monkeys climbing everywhere. At Cape Agulhas, on the southernmost a few metres from the frigid waters of the Atlantic Ocean to jump into the warm waters of the Indian Ocean.

The foursome performed at theatres in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Pretoria, and Durban, among other places. In a letter to her sons from Johannesburg on September 26, 1937, Ida wrote, “One hundred thousand people turned out to see Bebe, Ben, Popeye [another performer] and us. It was as good as a royal reception.” With only one exception, in Pietermaritzburg, the theatres were for whites only. They decided that wasn’t fair and, even though it wasn’t in their contract, they “hopped over between shows” to the Black theatres, as a February 22, 1938, article in the Toronto Star put it. Although they weren’t paid for those performances, they received bouquets and presents in return.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

After their tour of Africa, they returned to London. But in late 1938, when the authorities distributed gas masks to Londoners and the pair were advised to keep those masks within easy reach while performing, they sensed the rising tensions between Germany and England and made the decision to come home for good. Upon their return, they found that their sons had become accomplished musicians in their own right, with Harry Jr. playing clarinet and saxophone, and Ross playing trombone. Harry Jr. joined the RCAF Personnel Centre no. 3 concert and dance bands and was stationed in England from 1943 to 1946. In 1943, Ross joined the Central Command Band of the Royal Canadian Navy, stationed in Toronto, which toured Canadian cities throughout the Second World War.

With the economy on the upswing, Harry and Ida Culley found themselves in demand once again. On the newly established CBC Radio, they appeared on Canadian Cavalcade and Music for Moderns, playing compositions that the program schedule described as “highly idiomatic music of today that hovers somewhere between the symphonic and tomorrow’s hit parade melody.” Instrumental pieces such as “Insomnia” by Don Midgely merged classical forms with jazz melodies, often in several movements. Once more, the piano duo adapted to the latest trends, enchanting listeners from across Canada. “It is wonderful that two people can play the piano at the same time and yet the music blends together so beautifully,” a listener from Moncton, New Brunswick, wrote in 1940.

In 1948 Harry Culley became the music director of Toronto’s Royal Alexandra Theatre, built in 1907 and now a National Historic Site. He hired the musicians, wrote the arrangements, and conducted the orchestra that accompanied touring dramas, musicals, and dance performances, including the world-famous Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, which performed there in October 1955. Harry also played the organ at intermission during the hockey games broadcast on the radio from Maple Leaf Gardens.

With Harry’s steady income from the Royal Alexandra, the pair were able to rebuild their lives, buying a home in North Toronto in 1950. Ida stepped back from performing but kept her fingers nimble as a rehearsal pianist for the National Ballet of Canada. She also played for the young ballet dancers at Mosher’s Studios, who often performed at the Eaton Auditorium. She loved to play for her grandchildren, at family parties, and whenever she was asked.

Even though they were equals onstage, Harry looked after the business side of their careers, arranging their bookings, travel, and finances. Throughout their fifty-four years together, their personalities complemented each other — while he was a strong-willed perfectionist, she was an easy-going, impulsive charmer. After they both retired, they went on jaunts to Florida during the winter months in their Volkswagen Beetle, still tripping the light fantastic — him in a suit, tie, and straw hat and her in a light, silky dress. Harry Sr. occasionally performed on the same stage as his musician sons and taught piano to two of his grandchildren.

After Harry’s death in 1968 from lung cancer (he’d smoked cigarettes and a pipe all his life), Ida entertained war veterans as a volunteer pianist at Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. She continued to play the current hits. One of her favourites was Petula Clark’s 1964 song “Downtown,” which captured her love of the excitement of nighttime in the city.

One of my last memories of my grandmother before her death in 1983 is of a time when I was sitting with her on her front veranda. She asked me whether I could hear music playing in the distance. I listened carefully and said no, all I could hear was traffic noise. She told me the name of the song she heard; I nodded, thinking that she’d internalized music to such an extent that it had become part of her being.

Harry and Ida Culley made a lasting mark on Canadian musical history. At a time before widespread recordings, the pair brought new music live to listeners, helping to popularize the twentieth-century repertoire of standards we know today. They adapted continually to changing tastes by keeping up with the latest styles of music, new Broadway musicals, and Hollywood movies, playing solo, together, and accompanying singers and orchestras. A trailblazer, Ida paved the way for the generation of women musicians who followed, making a name for herself on the stage and in life, and showing that a woman could pursue her passion and have a family while living life to the full.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement