Toot Sweet: When Jazz Ruled Montreal

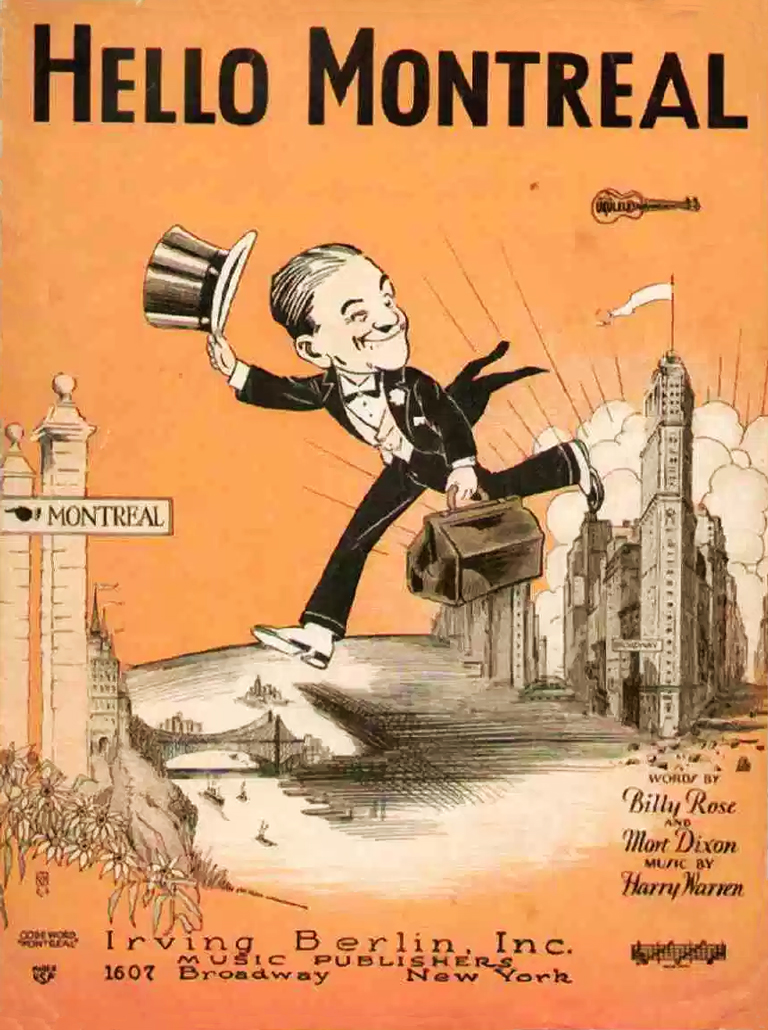

Speak easy, speak easy, and tell the bunch,

“Hello Montreal,” words by Billy Rose and Mort Dixon, music by Harry Warren. ©1928 Irving Berlin Inc.

I won’t go east, I won’t go west, I’ve got a different hunch:

I’ll be leaving in the summer and I won’t be back till fall,

Goodbye Broadway, Hello Montreal

The free-spirited and rebellious rhythms and melodies of jazz that sprang from the bayous of Louisiana found a fertile ground in what at first seems to be an incongruous locale — Montreal, a conservative town known more for chansonneries than for Charlestons.

But the lively, flashy, sometimes dangerous music took root. And for several reasons — geography, politics, history, organized crime, and race. Montreal would spawn some of the best-known names in jazz — Oscar Peterson, Myron Sutton, and Oliver Jones among them. It would also be temporary or permanent home to a host of travelling American musicians.

What brought many of them to Montreal was the city’s reputation for good times — likely because it was one of the few places in 1920s North America where booze could be bought cheaply and freely. The Quebec government never enacted prohibition laws as stringently as the rest of the continent — after a 1919 referendum, wine and beer were sold legally through licensed dealers and spirits were available through a doctor’s prescription. By 1921 these regulations fell by the wayside as the province established state-run liquor stores to sell spirits, and hotels and nightclubs were granted licences to sell beer and wine.

Thus Montreal became internationally known as the place to go for tourists seeking relief from the strictures of temperance. Simple economics tells the rest of the story — with more people coming to the nightclubs, the call for musicians to entertain them grew.

By the 1920s, jazz dominated popular music. Like the rock'n’roll that followed, its roots lay in Black communities in the United States, to be “discovered," and then appropriated for white audiences by white musicians. What was considered “real” jazz remained, for the most part, in the Black communities. When jazz music found its way north of the border, its history was no different.

The story of jazz in Montreal, especially in its early years, is directly tied to the story of the Black community in Montreal, which, though never very large in number, struggled to thrive in the face of blatant racism and limited economic opportunities. The community was late in developing. The furtrade economy of New France never needed the large number of slaves the plantation economy of the American South did. However, there were a number of slaves in the French colony — largely domestics, imported as status symbols for the growing aristocratic class. One of these was Marie-Joseph Angelique, a domestic slave for the household of Madame de Francheville, the wife of a wealthy merchant. On April 10, 1734, she ran away with her white lover and burned down the de Francheville home to cover her escape. Such an act could not be tolerated. Two months later she was recaptured, hanged, her body burned, and her ashes scattered.

Other Blacks in Quebec were free, and some became well known in the colony. George Bonga, for example, was a nineteenth-century voyageur of almost legendary strength who worked for the North West Company. George was considered to be an expert negotiator — a valuable skill in the fur trade.

Despite the indigenous community of freed slaves and refugees from the U.S. who arrived via the Underground Railroad, the Black community in Montreal remained very small compared to other provinces until the late nineteenth century, when the city’s economy began to boom. With canals, bridges, and railroads under construction, Black labourers were lured by the promise of jobs — from the U.S., believing they would be free from racial oppression in Canada, from Nova Scotia’s Black settlements, trying to escape economic privations, and from the segregated communities of Ontario. Slowly the community grew to a few thousand.

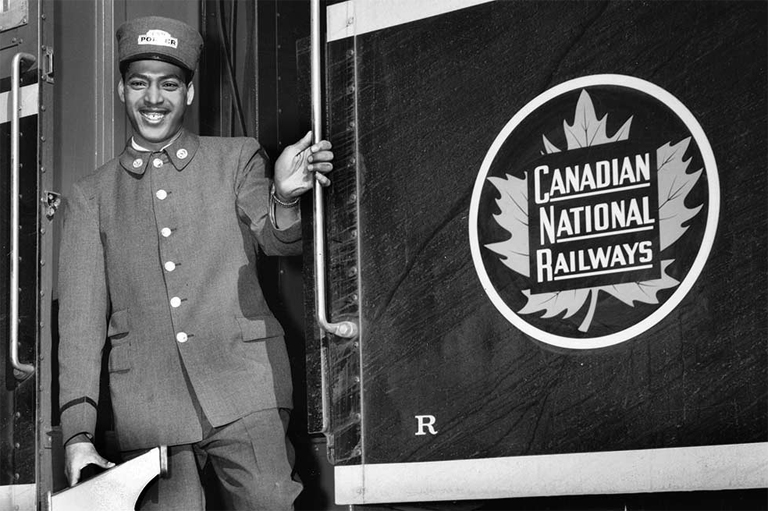

The real population boom didn’t occur until 1897 when Canadian railways, mimicking their American counterparts, began a policy of hiring Blacks as porters for their passenger service. Blacks fit the class prejudices of the white customers: they were thought suited to menial work, and could be paid less. They generally lived in the St. Antoine district of the city (named for the major street), where rents were cheap, and they had easy access to both major railway stations.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

For a long time, though, Canadian railways persisted in hiring only American and sometimes West Indian Blacks, ignoring the Canadian population. Though these men generally would set up apartments in Montreal, living and working in the city, they were not, as a rule, allowed to bring their wives or children north of the border. (The policy of importing Americans continued right into the 1930s, when Depression-era immigration controls finally forced the railways to end the practice.) The growth of a specific Black neighbourhood, especially one with a large number of single men with disposable incomes, created a market for Black entertainment venues.

The early decades of the last century saw the creation of a number of clubs for the Black population in the St. Antoine district. The first opened in 1897, and by the 1920s there were three. These catered to all the vices of single young men — drinking, gambling, and prostitution. The Nemderoloc Club (“Coloredmen” spelled backwards, in a slang style popular at the time) became particularly well known to the police and scorned by the larger Black community.

The nightclubs and jazz musicians were hardly the only cultural presence in the Black community at the time. There were several community associations and internationally affiliated groups active in the city then, all trying to work towards the improvement of Blacks in Montreal. These included the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the Negro Community Centre (NCC), the Coloured Women’s Club, and the nondenominational Union United Church. Not all of these organizations looked kindly on nightclubs, which often had criminal connections and had the tendency to sully the reputation of Blacks in the city as a whole.

Jazz music was intensely disliked by older generations, much like the rock’n’roll, rap, and rave music that followed. An article in the August 1921 edition of the Ladies Home Journal summed up the thinking of the time. In “Does Jazz Put the Sin in Syncopation?," Anne Shaw Faulkner declared that “Never in the history of our land have there been such moral conditions among our young people … the blame is laid on jazz music and its evil influence.” The article went on to claim that the syncopated rhythms of jazz damaged the brain.

An article the following June in the Montreal Herald elucidated the white establishment biases against the new musical form. Theodore Kosloff, a visiting Russian dancer, told the Herald that “jazz is doomed, the white part of North America is rapidly approaching a ‘morning after’ disgust for her spree of sensual, Negroid dancing.” He went on to claim that North Americans would soon devise their own dances and music — ignoring the fact that this is exactly what jazz was doing.

Many in Montreal’s Black neighbourhoods shared the view that jazz was an inferior music and provided classical music instruction for neighbourhood children instead, as a way of overcoming negative stereotypes held by whites. However, more than one youngster schooled on Beethoven would go on to play bebop.

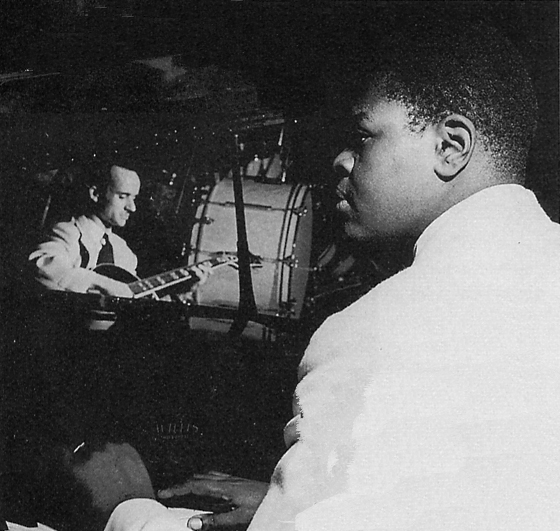

One of them was Harold “Steep” Wade, a saxophone player and pianist, who was one of the best-known musicians in Montreal in the 1930s and 1940s. In some ways he was the archetype of a jazz musician — hard living, hard talking, “cool,” and devoted to his music above all. Wade’s parents were not very musical, but they paid for his younger sister to take violin lessons and for him to take piano lessons, though he wasn’t enthusiastic. According to some, he shunned his lessons, and instead learned to play piano by watching the movement of the keys on a player piano. It wasn’t until he started to hang out at the famous Rockhead’s Paradise when the house musicians were rehearsing that he decided to take playing “the box” (as he called it) more seriously.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Jazz was as much an attitude and a lifestyle as it was a musical style. There were always two kinds of jazz, the commercial variety found in the clubs that largely catered to white audiences, and “real” jazz — hard-driving, high-energy music with more ragged rhythms and complex melodies. This was the jazz of the after-hours clubs, where jam sessions would go on until morning, where musicians, yearning to free themselves from the shackles of show-bar performing, would gather to play the more daring and experimental music that touring musicians brought from the U.S.

Wade was devoted to the music and to the lifestyle — perhaps at the expense of a more lucrative career in commercial music. For older musicians, the lifestyle usually included alcohol. For many, it included marijuana. By the 1930s it started to include heroin, to which Wade and his drummer friend Wilkie Wilkinson were thoroughly addicted.

Most jazz acts that came from Canada could only tour within Canada. Restrictive American labour laws forbade Canadian musicians from playing in the States if an American could do the job — unless the act was a solo attraction with name recognition. So, despite being one of the best “comp” (accompaniment) pianists in Montreal (the famed Oscar Peterson was considered to be more of a soloist), Wade was unable to succeed in the larger market to the south. His heroin addiction, which was probably known to the RCMP, likely would have made it impossible anyway.

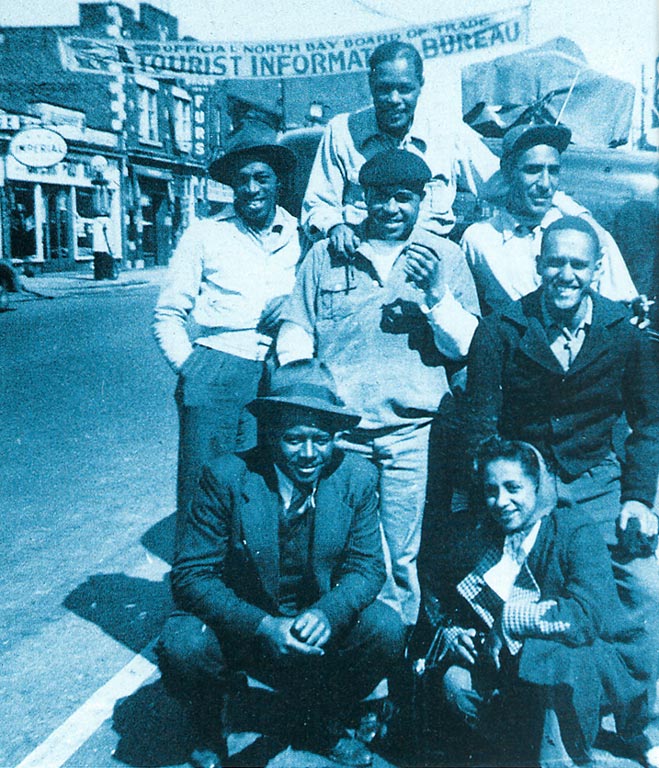

Wade was thus confined to Montreal, where he made his living on “the corner.” Here — where St. Antoine meets Mountain Street — Rufus Rockhead’s three-floor show bar was located. Facing it was the Café St Michel, where the famed American trumpeter Loui Metcalfe had his band for years, with Wade on piano. For a serious Montreal jazz musician, making your living on the corner was the measure of success.

Rockhead’s Paradise was perhaps the most famous bar in Montreal. Owned and operated by Rufus Rockhead, a West Indian immigrant, Rockhead’s opened in 1928. Legend has it that Rufus earned the seed money to buy the club by smuggling booze into the United States while working as a porter. Rufus would stand by the door of his club, always impeccably turned out, only allowing those people he knew by sight into the facilities, handing roses to the ladies. He always insisted on having the best musicians, and would often tell individual members of bands he hired that they were not good enough to play at his bar.

Recalls retired Montreal drummer Little Willy: “[When I was young] I used to go there to see my grandmother [a cleaner] in Rockhead’s all the time, and when there’d be rehearsals, I’d go over there and talk to the musicians. My grandmother always used to yell at me, 'Get away from those fellas!'"

These experiences inspired his own entry in the music business. Little Willy played in Montreal for decades, as a singer, and then as a drummer. His family had many ties to Rockhead’s — his mother was a showgirl there and his brother was a doorman.

“Rockhead’s, Café St Michel — if you could play at them places you could play anywhere,” he says. But the real money, he adds, was in the up-town “white” bars.

Racial sentiments of the day were also a factor in limiting Wade’s career. White clubs often would not hire Black bands, especially after the Depression hit. Once the popular Johnny Holmes Orchestra was nearly banned from performing at the Ritz Carlton hotel because they refused to play without their star pianist — a young Oscar Peterson.

Many clubs — even “Black” bars — refused to hire what were called “mixed” orchestras. The racial divide hurt Black and white musicians. Whites, many of whom played jazz in Montreal, could often only play with Black musicians in jam sessions after hours; the famed French-Canadian violinist Willy Girard was one of them.

Things started to fall apart for Steep Wade in the late 1940s and early 1950s. In 1949 Louis Metcalfe moved his band to the east end of the city. Wade quit a year later. He played less often, but he was seen around the neighbourhood bars just as frequently. He had a short-lived job at a small club playing for strippers, but that didn’t last. Friends started to notice he was more withdrawn and temperamental, his behaviour more erratic.

“Steep would sometimes fall asleep at the piano, but when he woke up, he always knew where he was,” recalls bass player Jack Kostenuk.

In December 1953 his wife Johann, an American showgirl, came home to their rooming house apartment to find Steep dead at the age of thirty-five. The diagnosis was natural causes, but most people who knew him believe it was “the heavy” — heroin.

Had Wade lived, it is doubtful he would have liked what happened to the Montreal jazz scene. Rock’n’roll made its appearance, as did prerecorded music in taverns. The election of Jean Lesage as premier and the re-election of Jean Drapeau as mayor in quick succession in 1960 turned around both Quebec and Montreal society. The Quiet Revolution, which broke the moral stranglehold of the Catholic Church, meant that the relatively innocent titillation offered by the show-girls of the chorus lines quickly gave way to strippers — who, at best, either wanted a simple grinding beat for musical accompaniment or brought prerecorded music.

Organized crime was huge in Montreal Gambling revenues alone brought in as much as $100 million a year in the years immediately following World War II — some years as much as $40 million more than the city’s tax revenues. Many police, reporters, and city hall employees were in the pocket of the Mob.

In order to appear to be doing something about crime, police would often padlock brothels or gambling houses — closing closets, false doors, and side entrances. One gambling house, which brought in a reputed $2.5 million every year, had forty-three “apartments” for a floor space of 170 square metres. The apartments were little more than cardboard boxes, assembled so the police could claim to have shut down the gambling operation at that particular address — even as the dice rolled behind them.

The crime bosses, though brutal to their enemies, were relatively kind to the musicians who played in their clubs. As one performer put it, “Whatever they did, nobody knew. It was nobody’s business, and they kept it that way. I’d rather work for them than anybody. You didn’t have to worry about your money, and nobody would bother you."

Though many musicians admit the crime was getting out of hand, they have few fond memories of Drapeau. The mayor’s campaign to clean up the city’s reputation and make it an international centre of industry and culture had the unintended side effect of ruining the city’s indigenous nightlife. In order to limit the influence of organized crime, Drapeau introduced restrictive licensing and limited opening times, which shut down a number of clubs that hired musicians. After-hours clubs, often the only place musicians could play the “real,” noncommercial jazz, closed.

Many clubs opted to cater to changing tastes and save money by becoming strip bars or rock clubs with canned music. Even the venerable Rockhead’s Paradise closed its doors by the 1970s after a failed incarnation as a dance club.

The St. Antoine district began to fail too as the industries that fueled its growth moved away. The community was dealt a succession of near-fatal blows through the 1960s when half the neighbourhood was bulldozed in favour of the Ville Marie Expressway and huge blocks of social housing. Renamed Little Burgundy, the neighbourhood is striving to recover from poverty, unemployment, crime, and an itinerant population. The jazz clubs and show bars are all gone. The only evidence that the neighbourhood was once the creative heart of Canada’s most vibrant music scene is a small swath of green space tucked between social housing developments, in the shadow of the massive maze of concrete overpasses — Le Parc de Jazzmen.

Canadian Firsts in Audio Recording

Canada can be accredited with many little-known historical firsts in the history of sound recording, both in Canada and the world. In 1888, for example, Thomas Edison made a phonograph recording Canada’s governor general, Lord Stanley, bidding the American president a diplomatic welcome to the Toronto Industrial Exhibition. Canada may not have realized it at the time, but it had just produced the world’s first political sound bite.

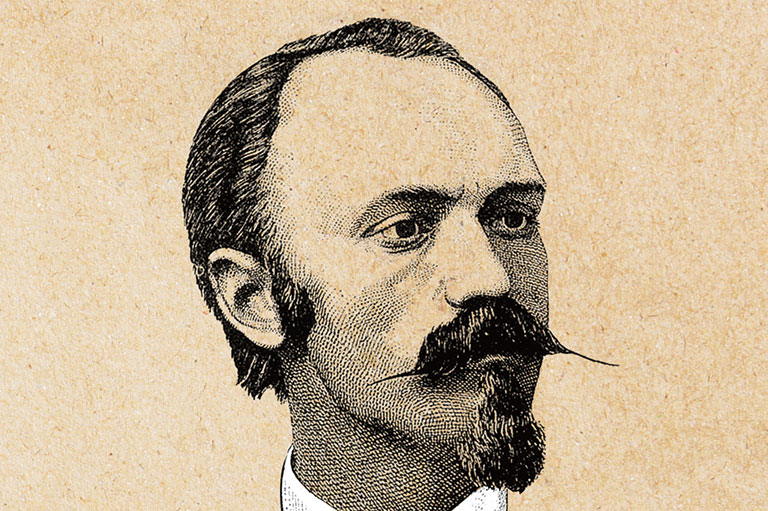

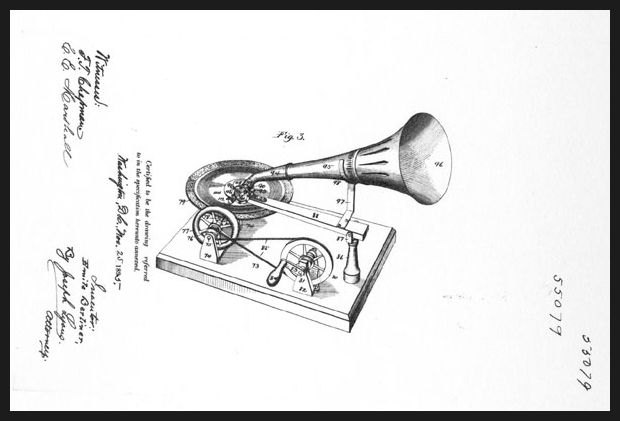

Canada would also give rise to the career of Emile Berliner, the German-born inventor of the gramophone. When he initially failed to successfully market his invention in the United States in the 1890s, Berliner sold his American patent to Elridge Johnson, who would use it to found the illustrious Victor Talking Machine Company. Regretting that he had lost control over his invention in the United States, Berliner decided to reassert it in Canada and by 1897 had obtained a Canadian patent and set up shop in Montreal.

Berliner’s Canadian gramophone dynasty can boast many firsts in the history of sound recording. Berliner was the first to record French-Canadian folk music, the first to record a speech by a Canadian politician (Finance Minister Sir Thomas White in 1918), and the first to adopt that now familiar trademark image of the fox terrier staring quizzically into a gramophone horn. Berliner’s son, Herbert, furthermore, would pioneer Canadian jazz recording in the early 1920s. Starting up Ajax, a record label of what was then called “race records” — so-termed because its intended audience was exclusively African-American — Herbert Berliner made the first recordings of jazz artists, such as Millard Thomas and his Famous Chicago Novelty Orchestra, who were from Montreal’s Black community.

Though Victor records would eventually buy out his company, Emile Berliner’s innovations left their mark upon Canada, and especially Montreal. Indeed, until after the Second World War, as jazz historian John Gilmore relates in Swinging in Paradise, Montreal was the only city in Canada where musicians could record.

— Text by Matthew Rankin

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.