Rocky Mountain Highlanders

It is 1901, and the Canadian Pacific Railway has paid Edward Whymper, the most famous mountain climber in the world, to visit Canada’s western mountains. By hosting the first person to summit Europe’s precipitous Matterhorn, the CPR hopes to reap an avalanche of publicity that will draw tourists to Western Canada and into the company’s mountain hotels.

Unfortunately, Whymper is an imperious alcoholic who alienates everyone around him. At a CPR hotel, he comes up against the manager, A.E. Mollison. Whymper has ignored the dinner bell, and the manager has twice informed him that his dinner is ready. Finally, a bellboy is given an order: “Go tell Mr. Whymper that if he is not here in one minute he will get no dinner.” Chastened, Whymper comes downstairs immediately. He has met his match in the form of a forty-one-year-old Scottish immigrant named Miss Annie Mollison.

In an age of separate spheres, when middle-class women were supposed to leave paid labour and business to men, it was highly unusual for a woman to manage a hotel — especially a first-class hotel. But for two decades around the turn of the twentieth century, Annie Mollison and her younger sister Jean Mollison were managers of almost all of the CPR’s acclaimed mountain resorts.

The Mollison sisters never married. To be a spinster in those days was often to be pitied, even mocked, for the business of women was to find husbands and raise children. Those who failed to do this often had to rely on the charity of relatives or inadequate handouts by local governments. Yet Annie and Jean Mollison succeeded in the male-dominated world of business. Free from the demands of husbands or children, their hard work, efficiency, good business sense, impeccable taste, and intuitive hospitality made them respected and even famous during the earliest years of tourism in the Canadian West.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Annie was born in Scotland in 1854. She was the eldest child of James Mollison, who worked as the chief factor, or manager, of a large estate. Jean, the fourth offspring, was born seven years later. James sent his children to the Inverness Royal Academy, a prestigious private school, where the boys were educated to be successful in business and the girls were taught to be young ladies, studying English literature, grammar and composition, French, drawing, needlework, and music.

Consequently, all the Mollisons spoke refined English, albeit with a pleasant Scottish accent. They were also capable of resorting to their native Scots dialect. Even after many years in Canada, Jean was once heard to exclaim, “You canna’ tak’ the breeks off a Hielanmann!” (you can’t take the pants off a Highlander) — a Scottish expression that essentially means, you can’t take away what a person doesn’t have.

In 1876 the mother of the family, Anne Bissett Mollison, suddenly died, leaving behind her husband and seven children. The eldest son was about to leave home, and Annie, aged twenty-two, would have stepped into her mother’s shoes, keeping the house and caring for her younger siblings. Twelve years later their father lost his job, took up farming in England, and then went bankrupt. By 1888 he was contemplating emigration to Canada, as it appeared to offer greater opportunities for his family.

His unmarried daughters were a special concern, for Britain had a surfeit of higher-class ladies and a shortage of eligible men. Annie, at the age of thirty-four, was considered doomed to permanent spinsterhood, but there was still a chance that the other daughters might find husbands. True, their father was in no position to offer dowries, but Western Canada had a surplus of bachelors looking for wives. And, while a fierce controversy raged in Great Britain about whether it was suitable for ladies to undertake certain new types of employment, such as nursing or typing, the Scottish journalist Jessie Saxby called Western Canada “a woman’s paradise of employment opportunities.”

Unfortunately for well-educated ladies, most of the jobs in Canada were as domestics, performing drudge work in private homes. Yet the CPR was looking for women who could supervise female hotel workers. And so Annie set off for Canada on her own, armed with a letter of introduction that led to her appointment as the housekeeper for the Banff Springs Hotel when it opened in June 1888.

Banff in those days was a small village in the Alberta district of the North-West Territories. (The province of Alberta would not be established until 1905.) Banff National Park had been created only a few years earlier, in 1885, and the place was just beginning to attract tourists. The park’s opulent Banff Springs Hotel was not the towering rundle-stone edifice that draws people today. It was a mere four storeys high, built of wood, and able to accommodate only about three hundred guests. But a guidebook of that era called it “one of the finest structures of its kind in Canada … furnished not only with ‘all modern conveniences,’ but with palatial luxury.” One of the luxuries was a bathhouse supplied with the supposedly therapeutic waters springing from nearby Sulphur Mountain. Indeed, at first the CPR tried to attract invalids as much as people wanting to enjoy the mountains — hence the word “springs” in its name.

As a housekeeper, Annie was following a tradition borrowed from the stately homes of England — think of the unflappable Mrs. Hughes in the television show Downton Abbey. In such homes the two most senior and best-paid employees were the male butler and the female housekeeper. He was in charge of the men on staff, and was directly responsible to the gentleman of the house; she was the equal of the butler, in charge of the women, and directly responsible to the lady of the house. Annie was therefore a senior administrator, reporting directly to the hotel manager. She supervised a staff consisting of chambermaids, who cleaned the guest rooms; domestics, who cleaned the public spaces; laundry workers; and a seamstress. She also would have visited the female guests every day to ensure that they were happy with their rooms and service.

By the middle of the summer, Annie had an assistant housekeeper — her twenty-seven-year old unmarried sister, Jean. Jean was passionate about music, and she would sing at the drop of a tam-o’-shanter — anything from Scottish folk songs, to popular ditties, to operas in French or Italian. Although Annie was also musical — her obituary in the Calgary Herald noted that she had been “a splendid pianist” who “contributed to many musical programs” –— she was less flamboyant and sociable than her younger sister, for Jean was a born entertainer who enjoyed being onstage, both literally and metaphorically.

Consequently, in addition to helping Annie supervise the female staff, Jean often entertained the hotel’s guests. She also sang at the opening of Banff’s Presbyterian church in 1888. Later, she would use her musical talents to ease her way into the upper-class social scene in Vancouver. During the First World War she even put on a travelling road show and dressed up as Britannia — complete with helmet, shield, and trident — to demonstrate her support for the troops.

Jean was passionate about music, and she would sing at the drop of a tam-o’-shanter.

Advertisement

In 1889 the CPR decided to close the Banff Springs Hotel for the winters due to a scarcity of tourists. Fortunately for the Mollisons, they had done such an excellent job as housekeepers that the company asked them to take over, as joint managers, the CPR’s Fraser Canyon House at North Bend, B.C., about 215 kilometres northeast of Vancouver on the Fraser River. Created by the CPR to avoid the expense of hauling dining cars up and down the steep mountain grades between Calgary and Vancouver, Fraser Canyon House was primarily a place to stop for a meal, although a few people stayed overnight to enjoy the scenery and other attractions. Once described by Jean as “a fashionable week-end resort for the elite of Vancouver and Victoria,” Fraser Canyon House was designed to resemble a Swiss chalet, in keeping with the CPR’s strategy of advertising the western mountains as the “Canadian Alps.”

The hotel had only a dozen or so employees, but the sisters had to ensure that the hungry guests, pouring out of two passenger trains a day, would find what the CPR demanded: “a strictly first-class Hotel Dining Station in the very best style.” The Mollisons needed almost military precision to ensure that the hordes of travellers were welcomed, fed, and herded back onto their trains to continue their journey without delay. Jean’s promotion from assistant housekeeper at Banff to co-manager at Fraser Canyon came about in part as a reward for excellent work, but also as compensation for an accident in which she badly injured her left hand when trying to fix a machine in the Banff Springs Hotel’s laundry. She lived up to her new responsibilities: Besides providing excellent service at the hotel, Jean and Annie landscaped exterior lawns and flower gardens that earned the admiration of visitors.

Indeed, the gardens at Fraser Canyon House were legendary when, in 1901, they caught the attention of royalty. A few days before the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York (later King George V and Queen Mary) stopped at North Bend on a cross-Canada tour, Jean was told to supply the royal train with forty baskets of flowers. “We were said at that time to have the most lovely lawns in Canada,” she recalled in an interview with the Vancouver Province in 1946. “I sent to the train a birch bark canoe full of flowers and a bunch of sultanas [impatiens], which the Duchess … wore as a corsage bouquet in Vancouver. Upon their return trip she insisted upon spending an hour in our gardens.”

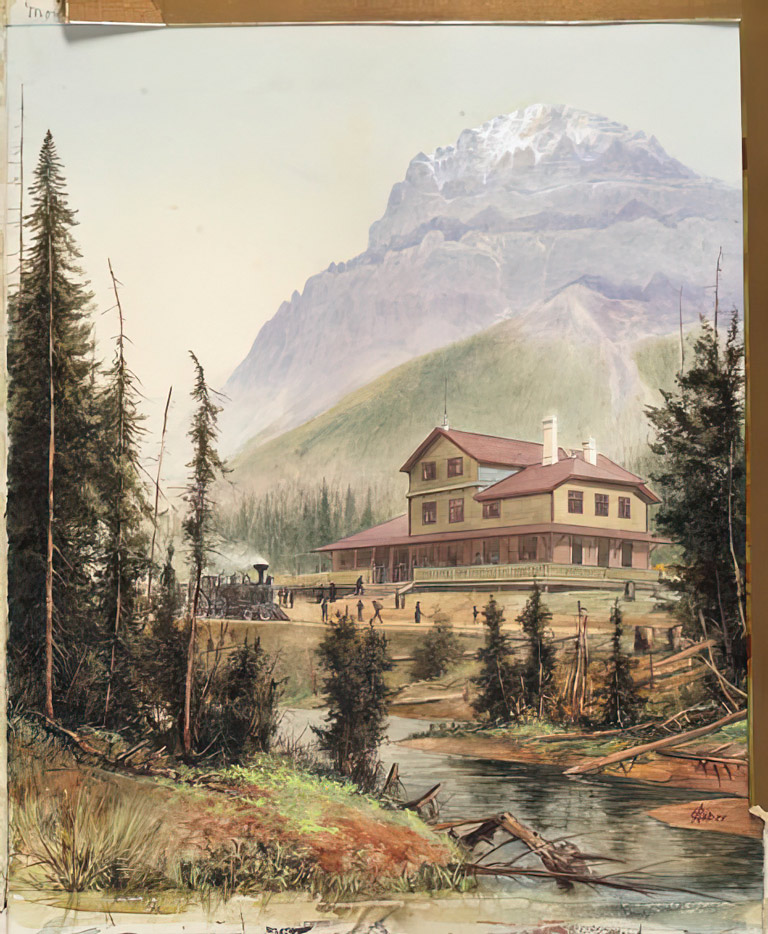

By that time, Jean was managing Fraser Canyon House without Annie, who had been sent in 1891 to the town of Field, B.C., about eighty kilometres west of Banff, to take over the poorly managed Mount Stephen House. Another of the CPR’s eating-stop hostelries, it was advertised as a “pretty chalet-like hotel” that was “a favourite stopping-place for tourists and mountain climbers,” with good fly-fishing for trout as well as hunting for bighorn sheep and mountain goats. In addition, it laid claim to being “a favourite region for artists, the lights and shadows on the near and distant mountains giving especially interesting subjects for the brush.”

The tourism industry had yet to truly take off — until the late 1890s Canada, and the CPR, were feeling the effects of an economic depression — but Annie and Jean were thriving. They even brought in their younger sisters, Jessie and Hellen, to help out in the hotels for a time, although both quit after getting married. Annie and Jean, by contrast, remained in the hotel business for their entire lives. They also remained forever single. Whether this was due to preference or a lack of offers is not clear, but it seems likely that, having achieved managerial status, they had no desire to give up their freedom for husbands and children.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Annie managed Mount Stephen House for about nine years, treating her guests with motherly solicitude. Mountaineer James Outram, who could wield a fountain pen as readily as an alpenstock, recalled staying at Mount Stephen House in his 1906 book In the Heart of the Canadian Rockies: “Tramping along one August afternoon, hot and dusty after nearly 20 miles [thirty-two kilometres] of walking, but well repaid by the feast of glorious scenery, the little Chalet looked delightfully cozy and comfortable to my brother and me the day we first approached its hospitable portals. Miss Mollison’s pleasant greeting made us feel at once ‘at home,’ as her tact and geniality invariably do, whoever the stranger may be. The domicile of ‘Scotland’ in the Hotel register appealed to her national instincts, the offer of afternoon tea was gratefully accepted, and when real Scotch shortbread was produced for our especial delectation our hearts were won for good and all! Thenceforward Field became my Rocky Mountain home.”

For a two-year interlude in the 1890s, Annie managed the CPR’s third eating stop and hotel, Glacier House, which stood close to Rogers Pass in Glacier National Park, B.C., about 135 kilometres west of Field. This was another promotion, as Glacier House was a mecca for tourists keen to “Kodak” the nearby Illecillewaet Glacier, and it was in the process of being renovated and enlarged. By the time Annie went back to Field, probably for reasons of health, Glacier House was immense, with at least forty bedrooms, a powerful telescope in an observation tower, two pianos, a bowling alley, a billiards room, a tennis court, and a croquet lawn.

Meanwhile, by 1896, in addition to running Fraser Canyon House, Jean had taken over summertime management of the CPR’s Lake Louise Chalet, about sixty kilometres northwest of Banff. The chalet, the forerunner of today’s Château Lake Louise, was a wood-frame structure a little smaller than a tennis court, with a large dining hall, a kitchen, and two bedrooms on the main floor and a dozen small rooms on the second floor under a sloping roof. Visitors in those days either walked or travelled by horse from the train station to what is now a world-famous beauty spot, although in those days the experience could be marred, not by hordes of tourists but by swarms of mosquitoes and horseflies.

“Miss Mollison’s pleasant greeting made us feel at once ‘at home,’ as her tact and geniality invariably do.” — mountaineer James Outram

On her first day on the job at Lake Louise, Jean proved that she could be as hard-nosed as her sister Annie. Upon encountering several drunken employees, Jean immediately sacked the lot and wired the CPR vice-president, Thomas George Shaughnessy, for some replacements: reliable Cantonese stewards from the company’s White Empress steamers that travelled between Vancouver and Asia. The company quickly complied.

Over time, Jean assembled a multicultural and eclectic staff. The 1911 census indicates that almost half of them hailed from Asia, and most of the others were recent British immigrants. She recruited Japanese bellboys, Chinese kitchen workers and waiters, as well as female administrative employees with musical talents.

“This is perhaps the first hotel that is conducted almost entirely by women,” wrote the Quebec journalist and politician Frank Carrel in his 1911 travel book, Canada’s West and Farther West. He added that the chalet’s tea room was “conducted, as every other department of the hotel is, by a number of very well educated young women, who all have some musical accomplishment, and in the evenings entertain the guests by singing or playing … piano and violin selections.”

Upon encountering several drunken employees, Jean immediately sacked the lot and wired the CPR vice-president for some replacements.

Jean herself often mixed business with pleasure, entertaining her guests with Scottish songs. She also poured her energies into both interior and exterior decoration. The British Pall Mall magazine mentioned “the Maple Room, a cosy nook lined with exquisite panels of pressed maple leaves designed by Miss Jean Mollison, the gracious chatelaine of the Chalet.” In 1898 she sowed the grounds with colourful Icelandic poppies.

Jean also became famous for the motherly care of her guests. Writing in Rod and Gun and Motor Sports in Canada, Rev. T.G. Wallace praised the Lake Louise hotel as “the most delightfully home-like comfortable resting place that one can find anywhere” and added: “Miss Jean Mollison was in charge and every Alpinist was loud in his praise of the courtesy and consideration received at the hotel.”

Her courtesy and consideration also extended to her staff. There is evidence that she paid them well and knew them as people, not just as employees. According to the 1911 census, the head gardener, Yen Gong — a married man born in China in 1863 who had arrived in Canada twenty years earlier — earned a respectable $720 annual salary, not bad in comparison to the average worker’s income in Vancouver of $785. In one instance, Jean even asked the CPR’s Shaughnessy (now president of the railway) to provide a free pass for a long-term worker retiring and returning to China. Shaughnessy agreed, although the ticket that he supplied was for steerage class, the cheapest level of steamship travel.

Shaughnessy, notorious as an iron-fisted administrator, strongly supported Annie and Jean. At one point, frustrated by problems with an early hotel administrator, he querulously inquired, “Is another Miss Mollison available?” Years later, dismissing a letter from an angry customer, he told Annie that in fifteen years of service he had never received a single complaint about her. He was also happy to provide the sisters with free railway passes for their father, who had also moved to Canada. After Annie left the company he gave her one, too, writing in a letter: “I take pleasure, personally, in enclosing you a complimentary [rail] pass.”

Yet, despite his praise and generosity, the CPR probably paid Jean and Annie less than what they would have received if they were men — a common practice at the time. The CPR does not reveal information about past employees, but census data indicates that, in 1901, Jean earned an income of $1,000, and Annie earned somewhat more, while Charles Taprell, manager of the CPR’s Hotel Vancouver, claimed an income of $2,400.

The sisters might have anticipated that, as women, they had a slim chance of ever being promoted to manage any of the CPR’s larger hotels, such as the Château Frontenac in Quebec City or the Hotel Vancouver. Whatever the reason, they left the company in the early 1900s and struck out on their own.

Annie left in 1902, and two years later she and Jean purchased a hotel in Calgary. At about that point Jean stopped running Fraser Canyon House, but she carried on at Lake Louise Chalet, while helping Annie with their Calgary hotel and also managing a Vancouver hotel. Meanwhile, the resort at Lake Louise was expanded and renovated every few years; by 1911 it housed well over two hundred visitors each day, with Jean supervising about seventy employees.

In early 1912, the CPR announced that, at Lake Louise, the manager of the Hotel Vancouver would be replacing “Miss Mollison, who has launched forth into the hotel business on a large scale of her own on Vancouver Island, buying one in Victoria and a second one on the outskirts.” The Mollisons’ CPR years had ended, and their entrepreneurial years were underway.

By the time the First World War broke out in 1914, Annie and Jean were co-owners of Braemar Lodge in Calgary, while Jean owned both the Glenshiel Inn in Victoria and Strathcona Lodge further north on Vancouver Island. She also leased Vancouver’s Glencoe Lodge and the CPR’s Cameron Lake Chalet, also on Vancouver Island. But all that is another story.

The Mollisons were unique in their time, enjoying almost a monopoly of the management of CPR mountain hotels. Although their names are no longer well-known, they have been memorialized in various ways.

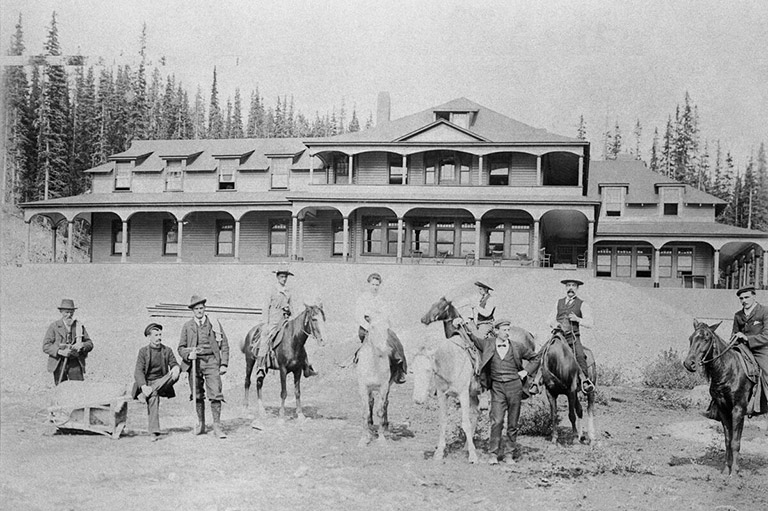

The American mountaineer J. Henry Scattergood named Mount Mollison in British Columbia in honour of Annie Mollison — “our kind hostess of the Mount Stephen House in Field, who had made possible my expedition” — after he became the first person to summit the peak in 1898. Jean has a room named after her in Château Lake Louise, based on her fame as a gardener. The story of the origins of the Icelandic poppies, which still grace the gardens, became a staff legend that continued long after the hotel had been further expanded and its name changed correspondingly from a modest chalet to a sophisticated château.

When the hotel was creating the Temple Wing in the early twenty-first century, Parks Canada required, as part of the development permit, that it should celebrate the natural, ecological, and human history of the area. Remembering the stories, the hotel’s general manager, David Bayne, suggested Jean’s name, and the result was the Mollison Room, with a biographical plaque and a photograph of Jean riding sidesaddle in front of the hotel. Appropriately — for she was the boss and loved being the centre of attention — she appears in the middle of the frame, surrounded by a clutch of alpine guides and trail riders.

Advertisement

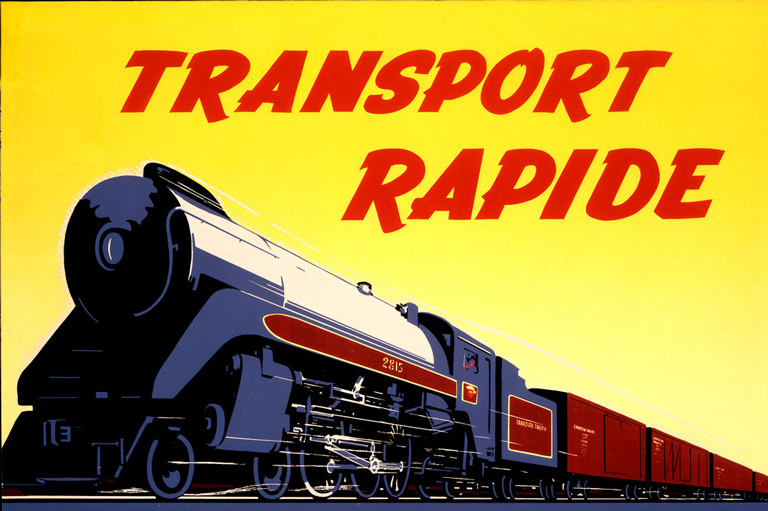

Life on the Railroad

Until passenger service began on the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1886, the only way to cross the western mountains was by foot or on horseback. Linking British Columbia to eastern Canada, the CPR ushered in a new era of trade, travel, and telecommunications. The hotels managed by the Mollison sisters were only part of the changing landscape wrought by the railroad.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement