A Bravura Life

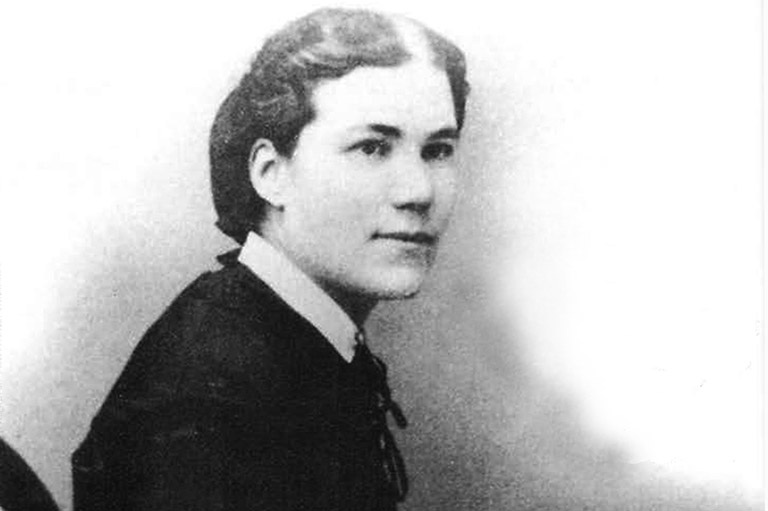

At 10:30 p.m. Ottawa time on July 1, 1927, Canadians all over the country sat around their bulky wooden box radios listening to the CBC’s first-ever nationwide broadcast. Across the crackling airwaves came the voice of a mezzo soprano who was a veteran of New York’s most famous stages, a woman raised in Victorian Canada who had not only sung for Asian kings and Parisian cognoscenti but had also lived an outré life that matched the exotic Javanese music she sang across North America.

Eva Gauthier’s program for this sixtieth Dominion Day did not feature such signature pieces as the Javanese “Anak Udang” (The Child of a Shrimp). Nor did she sing the jazz numbers or songs based on Stéphane Mallarmé’s symbolist poetry for which she was renowned. Instead, the international concert star celebrated for her mastery of complex music returned to her roots; she sang “À la claire fontaine,” a traditional French folk song that her first benefactors, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier and his wife, Zoé, would have known.

Gauthier’s father, Louis, had been one of the first French-Canadian engineers in the surveys branch of the federal ministry of the interior. He had been close to the prime minister’s family since his father, Séraphin, had cared for Laurier’s mother; the families were so close, in fact, that Laurier and Zoé (née Lafontaine) were married in a joint ceremony with Eva Gauthier’s aunt Emma and François-Aristide Coutu. (Some sources describe the Lauriers as Eva Gauthier’s aunt and uncle, but those were purely honorary appellations.)

Gauthier made her professional debut in 1901 when, at age seventeen, she sang at the funeral mass for Queen Victoria at Ottawa’s Notre Dame Basilica. With the Lauriers’ financial help, in late 1902 Gauthier went to study in Paris, where she stayed at the home of Joseph-Israël Tarte, Laurier’s minister of public works, and then in a pension (guest house) chosen by Lady Laurier.

As part of the French-Canadian diaspora, which roughly paralleled the English-Canadian one in London, Gauthier’s life in Paris resembled the chaperoned lives of heiresses in a Henry James novel, albeit without the money. Her letters, written in a spidery hand, more often than not on postcards, tell of visiting the Louvre and attending classical plays; they also describe the strengths, weaknesses, and odd habits of some of her vocal teachers.

The Lauriers remained close to Gauthier for the rest of their lives. In 1905, however, after Gauthier moved to London, they turned their patronage toward Eva’s sister, Juliette, writing cheques to support the aspiring violinist’s studies in Paris. Since Eva could not afford to stay in Europe on her own, Lady Laurier suggested that she write to Lord Strathcona, then Canada’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, asking for his support, which was forthcoming.

A few years later, Lady Laurier, who had already admonished Eva about purchasing an expensive Parisian wardrobe for her first Canadian concert tour, wrote an even stronger letter. “You have lived like the daughter of a millionaire,” the letter reads. “It’s high time you think of living on your own means.”

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Over the next five years, Gauthier continued her studies, first in London and then elsewhere, including New York and Milan. In 1905 she began performing with Emma Albani, the first internationally known Canadian opera singer, and two years later she sang in Carmen in Pavia, Italy. In 1910, after they had performed together in London, Albani said, “As an artistic legacy to my country, I leave you Eva Gauthier.” A command performance in Copenhagen led to Gauthier becoming the first foreign woman to be awarded the Order of the Queen. Gauthier turned down an Australian impresario’s offer of a three-year contract at $300 a week (more than $6,500 today) and instead reached for the brass ring: a role at Covent Garden in London.

What happened next could easily have been staged as a performance by the famous opera company. Just before the curtain was to go up on her premiere performance, Gauthier was dismissed. The devastated Gauthier believed that prima donna Luisa

Tetrazzini, fearing Gauthier’s voice would upstage her own, had arranged the firing. The resulting financial disappointment can be felt even through the Victorian prose of Lord Strathcona, who in a letter to Lady Laurier wrote that Gauthier had told him, “having carefully thought over the [professional] position, she has definitely decided to go out to Java to marry a Mr. Knoote.”

The man in question was Franz Knoote, whom Gauthier met while studying in Milan. Knoote managed a tea plantation in Java, and, while he reportedly loved Gauthier for the rest of his life, she soon regretted her decision to marry him. Once in Java, however, Gauthier quickly returned to performing concerts, and within a year she had added Malay to the languages she spoke.

At a time when most of the few Canadians who ventured to the Far East wore either the uniforms of the Royal Navy or British Army or worked for companies like the Royal Bank of Canada, Gauthier was taking bold steps into an unfamiliar culture. A Western woman performing in the Far East was almost unheard of, but that didn’t stop her from garnering rave reviews on a tour of China. In 1911, the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post called her “Canada’s Fairest Daughter” for a concert in which she sang a selection of arias and sentimental ballads, while according to the North China Daily News a “more beautiful voice or artistic singer has seldom, if ever, been heard in Shanghai.” More importantly for her career, Gauthier’s years in Java introduced her to traditional gamelan music.

To learn more about the distinctive Javanese musical style, Gauthier spent a month in the court of the king of Siam, where she met Anna Leonowens, who became the model for Anna and the King of Siam and The King and I. (Leonowens eventually moved to Halifax, where she founded the Victoria College of Art and Design, now NSCAD University.) Conscious of the value of notoriety, Gauthier titled an article for the Baltimore American about her time at court “Experiences in a Harem.”

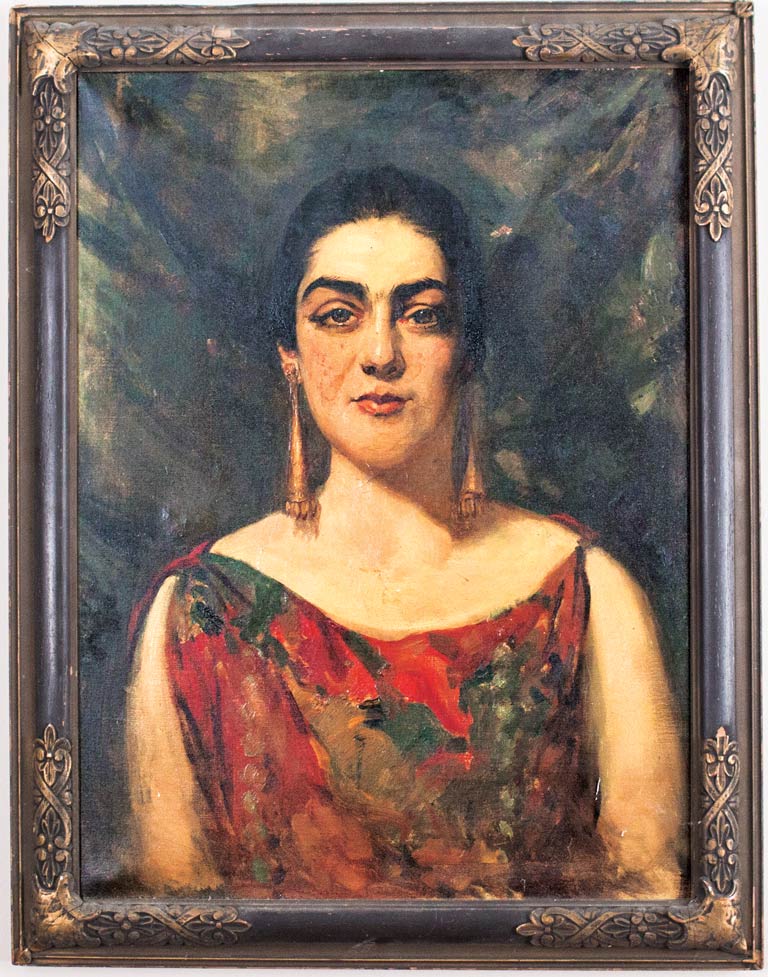

Gamelan music is produced by up to seventy-five instruments playing two different tuning systems, one expressing either the drama of sadness or happiness while the other, in the words of musicologist Jennifer Lindsey, portrays something more “majestic ... noble and calm.” This music, unusual to Gauthier’s Western ears, provided her with a unique oeuvre and her audience with a frisson of erotic exoticism, because of its foreignness and the all-but-diaphanous costumes Gauthier wore while performing

The outbreak of the First World War put an end to Gauthier’s plans to tour Europe and redirected her to New York, where she gave her first recital in December 1914 at the home of Frank Damrosch, the Metropolitan Opera’s chorus master.

Exactly where in the American musical firmament Gauthier’s performances fit was and remains problematic. Neither the public nor the critics quite knew — or, indeed, know now — what to do with someone who sang opera, Javanese folk music, and avant-garde jazz. To confuse things even more, Gauthier’s shows soon included suggestive dances by a performer named Nila Devi (Sanskrit for “Blue Goddess,” but actually an American exotic dancer named Regina Llewellyn Jones). The show, which Gauthier called Songmotion, was largely consigned to vaudeville, where sexuality could be displayed with a knowing wink.

Reaction varied widely and was not always positive. A full decade after the raw sexuality on display in the premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring caused a riot in Paris in 1913, Variety commented sniffily on Gauthier’s singing “in a foreign tongue” and Devi’s “snake like movements.” In response to “The Adoration of the Elephant,” the reviewer for the Los Angeles Times harrumphed, “if you are wise you will applaud and look learned.” He may not have liked the performance, but his response suggested that he recognized that Gauthier was presenting something new and challenging, perhaps even something important. A Winnipeg writer gave Gauthier a backhanded compliment by praising her for playing down the exotic and singing from The Barber of Seville.

Devi’s replacement, an English dancer who went by the name of Roshanara, introduced Gauthier to New York’s avant-garde music scene. By late 1917 Gauthier was performing works by Ravel, Stravinsky, and Rimsky-Korsakov at New York’s Aeolian Hall, which was second in prestige only to Carnegie Hall. Her sister Juliette had turned to the anthropological work of saving French-Canadian folk songs. Likely influenced by Juliette’s efforts, Gauthier included several of these pieces alongside the newer works and the Javanese songs in her concerts.

Immortalized by, among others, Ernest Hemingway and Canadian writers like Morley Callaghan and John Glasgow, the Paris that Gauthier returned to in 1920 bore little relation to the one the French-Canadian ingenue had experienced earlier. She was no longer the provincial girl who on her first sojourn to Paris had looked forward to packages of maple taffy and reading Ladies’ Home Journal, and who found the Moulin Rouge, in her words, “very odd.” Now, instead of chaste trips to the Louvre and the theatre, Gauthier became part of the group around composers Erik Satie and Maurice Ravel, the latter best known for the sensuous Boléro.

Her personal life reflected her convention-flouting professional activities. Not only was Gauthier married and divorced but she had also secretly borne a child out of wedlock at around this time. The boy was sent to the United States to live, although it’s not clear with whom. After Gauthier died, an American court recognized him as her heir.

Gauthier’s closeness to Laurier and, later, to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King — who fustily refused both Eva’s and Juliette’s entreaties for financial aid, claiming it would be improper for a bachelor to write either of them a cheque — indicates the family’s Liberal loyalties. So, too, does the way her “her father always recognized and respected his daughter’s commitment to her career” and, despite the family’s Catholicism, accepted Gauthier’s divorce, notes Quebec musicologist Nadia Turbide, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on the singer.

Of course, one limit was not tested; Gauthier’s family did not know of her son being secretly raised in Chicago. Had the Lord Chamberlain in London been aware of the boy’s existence, it is all but certain that Gauthier would never have received the large, heavy gilt-engraved card summoning “Eva Gauthier to Court at Buckingham Palace on Tuesday the 12th of June, 1928 at 9:30 o’clock p.m.”

The singer held another secret behind her French-Canadian Roman Catholic identity, one she hinted at in a 1923 concert. She included the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, the words and music of which were sacred to the Jewish part of her family on her father’s side.

Gauthier was also comfortable challenging prevailing social and political opinion. In the middle of America’s first “red scare” in 1923, she sang the “Hymn of Free Russia,” the national anthem of Soviet Russia, in public. In 1925, a year when seventeen African-American men were lynched, Gauthier wrote a letter to the New York Times praising the African-American Fisk Jubilee Singers for the “perfection of their rendition of songs with the art of true music as well as their spontaneity that gives life to any art.”

Thirteen years later, with her career in decline and war clouds again gathering over Europe, Gauthier used a radio address to criticize the Daughters of the American Revolution service organization for preventing the great African-American contralto Marian Anderson from singing in Washington’s Constitution Hall. In a letter to the organization she underscored the contributions of “great Negro artists.” Gauthier’s opinion was supported by Eleanor Roosevelt, at whose urging her husband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, allowed Anderson to sing from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

During the Second World War, Gauthier continued to sing and loaned her talents to war bond drives in both Canada and the United States. After the war, her performing career over, Gauthier taught master classes in New York. Despite her glittering career, she had never been wealthy, and now her finances were stretched. In those pre-Canada Council days, there was little government support available. Gauthier failed to secure a grant from the Canadian government or from several American foundations; a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation in early 1958 allowed her to pay five hundred dollars to two writers working on her memoirs, which were never finished.

Still, though living in the same sort of genteel poverty she had experienced as a student in Paris, and all but forgotten by the general public, Gauthier retained a commanding presence. One devoted New York concertgoer recalled that it was “a well-known fact that many concerts are incomplete until she arrives with her distinctive dress and queenly demeanour.”

Eva Gauthier died on Boxing Day in 1958 in New York. Though remembered by the New York Times, she was forgotten across Canada and even in her home city. There was no obituary in the Ottawa newspapers for the woman who, two generations earlier, was called “The High Priestess of Modern Song.”

Nice work if you can get it

After a 1923 concert by Eva Gauthier in New York, the popular bandleader Paul Whiteman asked to speak to her accompanist. Whiteman asked the pianist, George Gershwin, to write a piece for an upcoming concert, “An Experiment in Modern Music.”

According to Gauthier (if not also the Hollywood version of Gershwin’s life in An American in Paris), Rhapsody in Blue had its first public hearing a few weeks later, after a rehearsal of Gauthier’s show — which, incidentally, the critics did not like. In 1982, however, John Rockwell of the New York Times wrote that the concert “sparked Gershwin’s own interest in expanding his artistic horizons and being taken ‘seriously.’”

Gershwin and Gauthier stayed in touch; in 1935, he invited her to a party celebrating the opening of his opera Porgy and Bess.

Appropriate or appropriated?

Was Eva Gauthier engaging in cultural appropriation by presenting Westernized versions of Javanese songs while “surrounded by special scenery and a series of wardrobe changes” suggestive of Javanese dress? That’s a question raised recently by musicologists such as Anita Slominksa, who wrote her doctoral dissertation on Eva and her sister Juliette.

Even though Gauthier noted the havoc in Indonesia caused by the Dutch colonial authorities, the way she writes about the indigenous Javanese — “natives of an enchanting land” — and her acceptance (albeit only as an observer conscious of the Javanese social mores) of the practice of forcing twelve-year-old girls into arranged marriages, make for grim reading. However, in another article she observed that, because women of the court acted as go-betweens for the prime minister and the Sultan, the women “can shape the questions and answers with any construction they choose to put into them.”

Gauthier thought of her performances as a cultural bridge, the framework of which was a lecture in which she discussed “interesting bits of information concerning Javanese customs.” After all, she had gone from a bourgeois French-Canadian upbringing in Ottawa’s tony Sandy Hill neighbourhood to an environment that, as she described in a newspaper article, required checking under her bed for snakes and listening to the “screeching and chattering” of monkeys, tigers, and spotted leopards.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!