The Great Race

It was a warm, sunny autumn day as the special trains began arriving at Kenilworth Park around noon on October 12, 1920. More than twenty thousand fans, celebrities, gamblers, reporters, bootleggers, Pinkerton police, gangsters, and people of all stripes poured into the remote horse racetrack three kilometres outside the city limits of Windsor in Southern Ontario. The trains, coming from both Windsor and the neighbouring city of Detroit, Michigan, carried spectators tingling with excitement and anticipation.

The grounds began to buzz with people thrilled to know that soon they would be part of sporting history. They were about to watch the Kenilworth Gold Cup, a race between two of the world’s fastest horses — Man o’ War, a horse still considered by many today as the greatest thoroughbred racehorse of all time, and Sir Barton, voted 1919’s American Horse of the Year by the National Thoroughbred Racing Association, the Daily Racing Form, and the National Turf Writers and Broadcasters. “Never, probably, in the history of the world has a race aroused such great interest,” gushed a reporter from the Windsor Star.

Some in the crowd, however, found that the venue put a damper on their enthusiasm. Reporters arriving from cities in the United States were staggered by the remoteness of the track. “On a prairie, out of sight of any habitation,” was how the New York Times described it. The San Francisco Examiner called the site “barren,” while the Brooklyn Daily Eagle grumbled: “What a sad commentary on the sportsmanship of American turfmen that this race, the greatest of all history of the American turf, should have for its setting Kenilworth park.”

How did this come to be?

It was thanks to two Canadian horse-racing aficionados. One was a dashing millionaire who was burning through his father’s fortune with astonishing speed; the other was a shrewd businessman who had a knack for taking money off of gamblers.

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The massive crowd parted like the Red Sea as Commander J.K.L. Ross and his entourage strode to the paddock just before noon. Spectators strained to get a glimpse of the glamorous Commander — so named because, in 1915, he had purchased one of the fastest civilian turbine-powered yachts in existence and donated it to the Royal Canadian Navy to patrol the Canadian east coast for German U-boats. The ship was converted to a torpedo boat, christened HMCS Grilse, and Ross was given command of it.

The Commander — who had inherited more than $12 million from his father, James Ross, one of the builders of the Canadian Pacific Railway — was known for his gregarious personality. But on that day at Kenilworth, the Commander did not wear his trademark smile. Ross was troubled. He had a lot to lose, and, like most gamblers, he knew the odds. Today — the day of what many horse-racing fans still consider to be the greatest match race in the history of the sport — the odds were against him.

The horse he had entered in that day’s race was Sir Barton. A foal of 1916, Sir Barton was a stocky horse with a pugnacious attitude. The previous year, 1919, Sir Barton had swept the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes, and the Belmont Stakes — a string of classic races that would later be called the Triple Crown. The term Triple Crown, however, only began appearing in print during the 1930s, far too late for Sir Barton.

On that October afternoon, the ornery Sir Barton would meet the incredible Man o’ War. The regal Man o’ War, often referred to as Big Red, had captivated the world; his phenomenal stamina and power had elevated him to near supernatural status. Standing next to Sir Barton, a horse of average proportions, the massive stallion cut an intimidating figure.

“Had he been parading with a host of other thoroughbreds, excluding Man o’ War, Sir Barton would have been proclaimed a wonder. But next to the champion of champions, he looked rather insignificant,” a New York Times reporter wrote. The betting public, dazzled by Man o’ War, made him a twenty-to-one favourite.

In the relative tranquility of the paddock, the Commander considered his horse. Sir Barton’s feet were tender. The surface of the Kenilworth racetrack was hard and likely to bother him. Just hours before the race, the Commander made the difficult decision to replace Sir Barton’s usual jockey, Earl Sande, with the more seasoned and steely Frank Keogh. “My boy is not in good form, as his recent performances show,” Ross explained in announcing the substitution. “I would rather win this race today than all the other races in which Sir Barton may participate. Keogh is at the top of his form at present and I want to take advantage of it.”

But could the veteran jockey ride the cantankerous colt to victory?

Advertisement

Among those waiting for the race to begin was Abraham M. Orpen. Orpen was responsible for having this historic race relegated to such a minor track. Without him, the great race would not have found its way to Canada.

In his own way, Orpen was as much of a character as the Commander. Born in Toronto, the son of Irish immigrants had a talent for making money. He earned his first fortune running the Alhambra saloon on Toronto’s Church Street. He branched out into gambling operations and bookmaking, while also establishing businesses in construction, mining, and lumber. Whatever he was doing, he was never far from a racetrack, and over time he owned and operated several.

Weighing over three hundred pounds, most of the time he worked behind the scenes, a silent, skilful operator known to most as “Abe.” He was also a philanthropist who ran a soup kitchen during the Depression and who had a soft spot for gamblers, advising them not to bet even as he took their money.“

Betting on the horses is a losing proposition,” Orpen once said. “It is a game the public cannot beat. Once, twice, or oftener the bettor may win, but if he follows the game day in and day out he will always end a loser.”

Orpen was good at spotting opportunity, and he saw one in the fact that betting on horses was illegal in the state of Michigan — yet the biggest city in the state, Detroit, lay just across the eponymous Detroit River from Windsor. When New York banned gambling on horse races in 1908, the hard-up gamblers of two American states could get their fix simply by crossing the border into Ontario.

By 1916 Windsor had three racetracks, including the Kenilworth track co-owned by Orpen and three other Toronto businessmen. Orpen and his partners built the stands at Kenilworth using the steel from the original Kenilworth racetrack in Buffalo, New York, which was dismantled in 1915 after the demise of horse-race betting in that state.

Orpen saw another opportunity when it became clear that a match race between Man o’ War and Sir Barton was in the cards. With Sir Barton owned by a Canadian who favoured holding the race in this country, Orpen saw no reason why the race could not be run at his obscure little track. He went to work to quietly outbid eager American track owners who wanted the match on their soil.

Orpen offered an astonishing $75,000, plus a gold cup, to the winner. That was $25,000 more than the owners of both horses had already said they were willing to accept. Orpen hurried to close the deal before his nearest competitor — businessman Matt Winn, who had made the Kentucky Derby famous — could make a counter-offer. Winn, vice-president and general manager of the Kentucky Jockey Club, wanted to have the match held at his track in Louisville — a location more naturally suited to a race of this magnitude. He was deeply chagrined to learn that he had missed the opportunity.

Many felt it was a poor risk for Orpen to lay such money out for the race, but this did not seem to worry Orpen. He was more concerned about an irritating detail that he had to deal with. Although he had won the bid, two-horse match racing was actually illegal in Canada. So he found a way to skirt the rule by a simple ruse: He entered a third horse, an undistinguished colt named Wickford, and then quickly withdrew him before race time.

By mid-afternoon, the moment had arrived. The magnificent horses, their owners, and the jockeys left the paddock and headed to the track. Jim Ross, the Commander’s son, would remember that walk as “noise, unceasing noise.” In the grandstand, Ross and his entourage took their seats in a private box festooned with his racing colours of black and orange; in the adjacent box, decorated with black and yellow, sat Sam Riddle, the American owner of Man o’ War, and his coterie.

On the sidelines, a dozen movie cameras waited to capture the race for posterity. The resulting movie, the first made of a horse race, was Orpen’s idea. He did not do it for the historical record but for the money to be earned by showing the footage in movie houses across North America. (Silent black-and-white footage can today be seen on YouTube.)

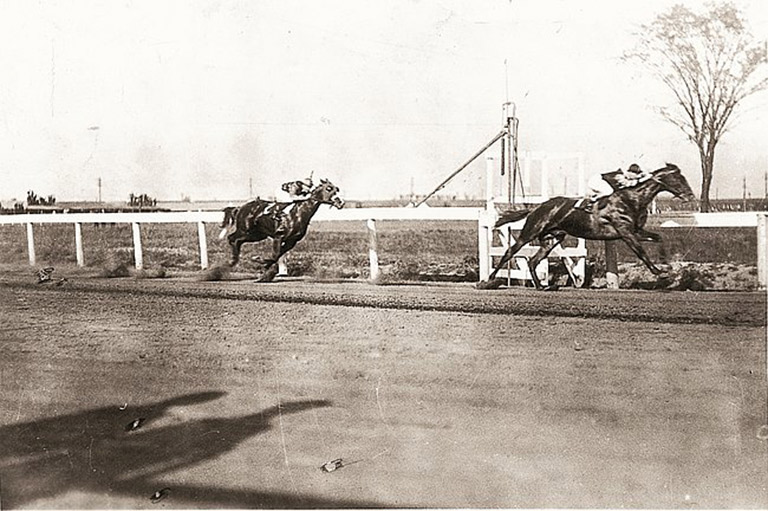

The flag dropped to signal the start. Sir Barton leaped to the lead. The smaller horse had drawn the starting position closest to the rail, giving him the advantage on the opening bend. But as they rounded the bend and came into the straight Man o’ War bounded ahead, thundering past the awestruck crowd in the grandstand. “The moment Man o’ War flashed past the stand at the first quarter it was apparent to everyone in the crowd that Sir Barton, game as he was, could never catch that fast flying golden colt with the tremendous stride,” the Boston Post reported.

Sir Barton battled bravely, but the incredible power of Man o’ War was too much. “Around the turn and down the backstretch Man o’ War sped along at a terrific pace,” wrote the New York Herald. “Sir Barton ... fought on courageously, but Man o’ War was his master and try as he might he could not get within striking distance.”

Rounding the final turn, Man o’ War “bounded forward and gained three more lengths,” the Herald reported. The front-runner galloped down the home stretch and crossed the finish line seven lengths in front of an exhausted Sir Barton.

It was often said of Ross that he always won without a boast and always lost with a smile. True to form, after losing the race he had hoped to win more than any other, the Commander warmly grasped the hand of Riddle and, according to a report in the Toronto Globe, congratulated him with the words: “Well it’s over. The best horse won. My hearty congratulations, Riddle.”

As for Abe Orpen, his gamble paid off. When the gate receipts were tallied, he counted over $100,000 in ticket sales alone. And in an era of shady bookkeeping and a world of often illegal gambling, how much the Canadian entrepreneur reaped from the race taking bets, selling refreshments, and on outside deals will never be known.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

What happened to the horses and men after the greatest race of their lives? Man o’ War never raced again. Following his undefeated season of eleven straight wins, the superstar horse was shipped to Faraway Farm in Lexington, Kentucky, to stand at stud.

Over his two-year career, Man o’ War won twenty of twenty-one races, setting three world records, two American records, and three track records. Man o’ War died in 1947 at the ripe age of thirty. In 1999, the Blood-Horse magazine ranked Man o’ War number one in its list of the top one hundred U.S. thoroughbred champions of the twentieth century.

Sir Barton retired to stud that year, virtually forgotten by the public. When he did not turn out to be a productive sire, he spent most of his life as a working horse with the U.S. Army Remount service in Fort Robinson, Nebraska. Sir Barton died of colic on October 30, 1937, and was buried on a ranch in the foothills of the Laramie Mountains in Wyoming. His remains were later moved to Washington Park in Douglas, Wyoming. Sir Barton was posthumously recognized by the governing body as the first winner of the Triple Crown, and a memorial was erected to honour him. The Blood-Horse magazine ranked him forty-ninth on its list of one hundred U.S. thoroughbred champions of the twentieth century.

J.K.L. Ross continued to squander money. Soon his fortune dwindled. In 1927 he disbanded his stable, selling his top horses at auction and his Agincourt Farms north of Toronto. A few years later he left Canada and retired to a life of sailing and fishing in Jamaica. He died in 1951 and, by his wish, was buried at sea.

Abe Orpen continued to beat the odds. Despite his massive weight he lived until 1937, wheeling, dealing, and enjoying life. As his obituary in the Windsor Star said: “The man who built a shrine at the feet of Lady Luck and successfully wooed the fickle maiden as few have wooed her, is dead at age eighty-three.”

Kenilworth Park racetrack closed in the 1930s, a victim of the Depression and of the legalization of horse-race betting in Michigan in 1933, which stemmed the flow of gamblers from Detroit. The track and associated buildings were demolished. Today, a children’s playground in Windsor bears the name Kenilworth Park, a reminder of the once-celebrated racing venue.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement