Thundering Chuckwagons

Hyawww! Out of the Marigold-coloured prairie sunset come the creaking, jangling, and charging Canadian cowboys and their chuckwagon outfits! If you’ve never seen them, you’ve never witnessed the most skilled teamsters on the planet hurtling around a dirt racetrack at speeds approaching sixty-five kilometres per hour. Chuckwagon races are a team effort by horses, outriders, drivers, and their families — a collaborative venture of Canadians travelling prairie highways to racetracks across the West.

The Calgary Stampede held its first chuckwagon races one hundred years ago, in 1923. The races owe their existence to the first chuckwagons that criss-crossed the American plains after the U.S. Civil War and later travelled the Canadian prairies and foothills. These mobile prairie cookhouses sustained the men trailing and caring for cattle. Eventually, boastful talk between rival outfits turned to the question of who had the fastest horses and wagon. Well, there was no better way to find out than to have a race. Join us for a breathless dash through a hundred years of chuckwagon thrills and spills!

From Range to Rodeo

In the early races on the open range, wooden wagons careened across gopher-hole-filled fields, with Dutch ovens, water barrels, plates, flour, and beans flying around. It was bedlam as the loaded wagons dashed to get to the best campsite or to pull up to the closest saloon.

Eventually, the charismatic Guy Weadick, who organized the first Calgary Stampede in 1912, was asked to attract more ticket buyers to the 1923 event. Weadick invited his ranching friends from around Calgary, and they hesitantly brought their valuable, heavy, working chuckwagons to take part in the inaugural races. Together, they collaborated to design a unique and spectacular horse race. Within a few years, the Rangeland Derby became the Calgary Stampede’s marquee event. Professional chuckwagon races soon took hold across the West. Canadian rodeo venues, unlike American rodeos, often had racetracks as part of their infrastructure, thereby fostering the sport in Canada.

Today’s chuckwagon races remain similar to those early races. When the starting klaxon sounds, an outrider tosses a small rubber keg, replicating the stove, into the back of the wagon, and the wagon drivers steer their four thorough-bred horses through a figure-eight pattern around two barrels. The two outriders jump onto their horses and follow their chuckwagon around the figure eight. The entire outfit then gallops once around an oval racetrack to the finish line. While avoiding penalties, the outfit tries to achieve the fastest time of the night.

Chuckwagon racing has been called Alberta’s national sport. Yet, over the decades, chuckwagons have captivated fans across the nation, including in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Montreal, Ottawa, and even Toronto, where chuckwagons raced at the city’s exhibition grounds in 1926 in the seven-day-long Western Stampede and Rodeo. Ten decades since its debut, chuckwagon racing remains the only professional sport Canadians can exclusively call our own. It is Canadians who organize and compete in professional chuckwagon races. The talent pool in this co-operative endeavour is small: There are fewer than one hundred Canadians capable of racing outfits at the professional level.

The inimitable tradition of chuckwagon racing reflects the Canadian rangeland trait of caring for and nurturing both animals and people — it’s an exceptional community venture that centres around treasured partnerships between willing thoroughbred racehorses and Western families.

Pancakes and Bacon

Synonymous with chuckwagon racing is the hospitality of free pancake breakfasts. Like the race itself, downtown Calgary’s first chuckwagon breakfasts occurred in 1923, when Wildhorse Jack Morton’s chuckwagon outfit stormed down Ninth Avenue, set up a wood-fired stove, and began dishing out rangeland chow to eager passersby. The cowboys’ merriment was infectious, their kindness and generosity catching, and the chuckwagon breakfast tradition was born.

For many years, the chuckwagons used in the nightly races were also seen serving breakfast, as shown in this photo. Today, specific chuckwagons, used only by the Calgary Stampede’s Downtown Attractions Committee, serve up free breakfasts of pancakes and bacon to thousands of locals and tourists. The range chuckwagon ethos of caring for people and welcoming strangers continues to be a keystone of chuckwagon racing and its people.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Cowboy Cartoonist

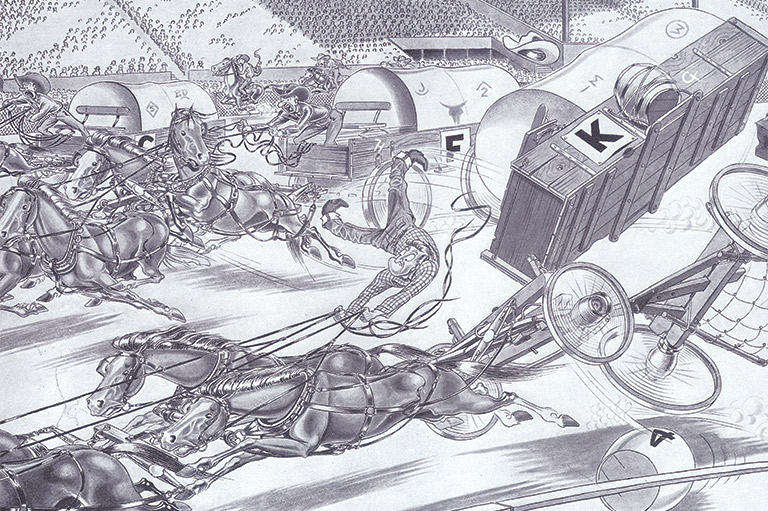

A cowboy at heart but a cartoonist by profession, Stew Cameron drew some of the liveliest chuckwagon-racing pictures ever conceived. Born in 1912, the year of the first Calgary Stampede, he spent his summers as a student running a pack string of horses in the Rockies. Cameron gained first-hand knowledge of horses’ stubbornness as well as their trustworthiness, and he became fond of the cowboys who negotiated daily with their equine cohorts.

After a stint at Disney Studios, where he drew for the animated movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cameron joined the Calgary Herald in the 1930s and earned editorial fame lampooning Alberta Premier “Bible Bill” Aberhart. After serving in the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Cameron returned to Calgary in 1949 and continued drawing freelance cartoons. Cameron’s lifelong passion for the Calgary Stampede and its chuckwagon cowboys never dulled. His cartoons, especially in the 1930s, reflected the early races’ rambunctiousness: Wagon wheels fell off, chuckwagons split, and cowboys were ejected from their steeds. After Cameron’s death in 1970, his family curated some of his best Calgary Stampede cartoons and published four slim books in 1972. This rowdy chuckwagon image originally appeared in Cameron’s 1949 collection What I Saw at the Calgary Stampede.

Risks of the Race

Chuckwagon racing is thrilling to its fans but cruel according to its foes. The incidents of overturned wagons and tossed cowboys have been reduced by new safety rules over the decades, but it remains an action-packed event where accidents occur and horses are sometimes fatally injured. In the last ten years, fifteen horses have been euthanized, due to either accidents or leg injuries, in Calgary Stampede chuckwagon races.

Critics like the Vancouver Humane Society advocate an end to chuckwagon racing, saying it puts horses at undue risk of injury and death. This viewpoint has spread, as public opinion about using animals in entertainment has modified since professional chuckwagon racing began. The year 1986 also marked a turning point, when a serious crash at the Calgary Stampede grabbed national attention. During a chuckwagon race on July 10, a horse tripped after stepping into the stove rack dangling from the back of a wagon that had cut in front of it. The ensuing collision resulted in the deaths of five horses.

In 1987, the chuckwagon community responded by implementing new safety measures, including random alcohol and drug testing and tougher sanctions for drivers who commit dangerous infractions. The chuckwagon’s design was changed, too, removing the dangling stove rack and moving it inside the chuckwagon.

Since then, the chuckwagon community continues to adapt and to implement new safety rules. In 2011, the Calgary Stampede reduced the number of outriders from four to two and implemented the Fitness to Compete program. All competing chuckwagon horses are now microchipped. This allows veterinarians to record horses’ health inspections, drug tests, and their rest days — one day of rest after three consecutive days of competition, or two rest days after four days of competition. In 2021, the number of wagons racing per heat was also reduced from four to three.

Chuckwagon families understand critics’ well-intentioned sentiments but respond that their criticisms are often coloured by a lack of experience with thoroughbred husbandry. Each fall and winter, contemporary chuckwagon cowboys tour North American racetracks, find thoroughbred horses whose racing careers are over, and give them a new opportunity with chuckwagons.

Since keeping a racehorse is expensive, this is often a thoroughbred gelding’s only chance to avoid the abattoir. Farriers, horse chiropractors, equine dentists, veterinarians, and specific exercises are all part of the horses’ year-round care and training regimens.

Cracking the Whip

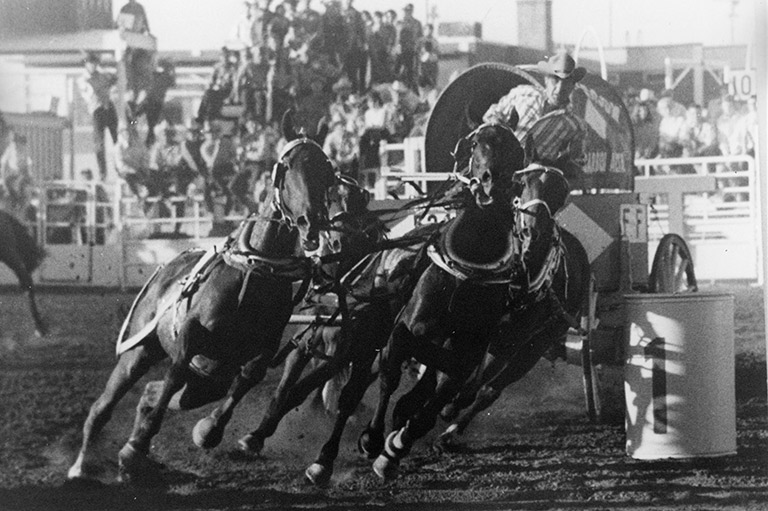

Whips were allowed for the first twenty-five years of wagon racing, as seen in this 1938 photo of driver Jim Baxter. Drivers avoided hitting their horses with the whip, since that caused the horses to break stride and slow down. Rather, it was the sound of a snapping whip that motivated the animals.

Drivers capable of operating a whip while holding four reins in the other hand were truly confident and capable teamsters. Some outfits carried a “whip man” whose sole job was to operate a whip. This was the only circumstance where two people were allowed on the driver’s seat.

However, whips were problematic. Unsuspecting outriders sometimes found wayward whips wrapped around their necks, yanking them off their horses and into the dirt. Judicious outriders passing a flailing whip buried their heads into their horses’ manes, avoiding the driver’s leather tentacle. Whips were banned in 1948, an evolution that improved safety for everyone involved.

Advertisement

Ice Stampede

Beyond the dirt track, chuckwagons figure conspicuously in Southern Alberta’s identity: from chuckwagon-themed airport kiosks to playground structures and tiny free libraries. This chuckwagon culture once included an event called the Ice Stampede. Each winter from 1944 to the mid-1980s, Boy Scouts from across southern Alberta — like Calgary’s 2nd B Cub Pack of Christ Church, pictured in this photo — gathered in Calgary to race “chuckwagons” on ice.

The child-sized all-wooden wagons, set on ice runners, were pulled by a team of four skaters instead of horses. Three more boys acted as outriders, while the smallest boy sat in the wagon as the driver, and one of the strongest boys grabbed on to a six-foot-long rope attached to the wagon’s rear. His vital job was to prevent the sliding wagon’s rear end from careening uncontrollably around the barrels and the arena’s corners. After turning the barrels, the younger Scouts (boys up to ten years old, called Cubs) skated one lap, while the older Scouts skated around twice. Girl Guides joined in the mid-1970s. The teams completed a perilous lap in as little as thirty seconds in riotous races full of tumbles and speed, with wagons careening, kids falling, and families and friends cheering.

One Muddy Outrider

The rain poured down at the 1965 Calgary Stampede, turning the track into a muddy soup with a hard bottom. Outrider Lark Isbell was riding a horse called Tony, “a hard-mouthed ol’ devil that liked to be with the wagon,” Isbell recalled.

At the race’s start, Isbell tossed his stove into the wagon and ran with his horse. “At the top barrel, when I went to jump on Tony, Orville Strandquist [a second outrider] had already mounted his horse. Orville’s horse crowded over against me when I went to make my jump.” Pinned between the two outriding horses, Isbell was carried onto the track.

When the horses parted company, Isbell dropped feet-first to the ground. “Normally, if you hit the ground, the speed of a horse running will kick you into the saddle. But that year, with the track being so deep with the mud, when I dropped to kick into the saddle, instead of kicking off the ground, that ground sucked me in.

“As I went down, my hands were jerked off the saddle horn. I grabbed for the stirrup and missed it.” Isbell then hung on to the lead line. “Being on the end of that line didn’t mean a thing to Tony. He carried me right along for about a hundred yards. ... I finally lost the last knot of the lead line and slid to a stop. I picked myself up, and my legs were sore where ol’ Tony had stepped on me a little bit.” Isbell hobbled back towards the grandstand, where Calgary Albertan photographer Randy Hill took this award-winning front-page photo.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The King

In 1974, twenty-two-year-old Kelly Sutherland stood at centre stage of the jam-packed Calgary Stampede grandstand clutching the bronze trophy from his first Rangeland Derby victory and proclaimed: “I’m just the happiest kid in the world.” Hailing from Grande Prairie, Alberta, Sutherland first raced in Calgary in 1969 at age seventeen and continued racing until the Calgary Stampede’s mandatory retirement age of sixty-five. Nicknamed “the King” by announcer Joe Carbury, Sutherland was the competitor to beat for five decades. He won shows across the West, including a record-setting twelve world championships and twelve Calgary Stampede championships.

But a jubilant outrider named Butch David nearly cost Sutherland that first crucial victory in 1974. Just before David crossed the finish line, he elatedly threw his hat in the air. “It was only a foot away from the other outrider. He’d have [been penalized for] interference if it had come down and hit the outrider behind him,” a judge told Sutherland after the race. In 2020, Sutherland was inducted into the Alberta Sports Hall of Fame.

Wagon Women

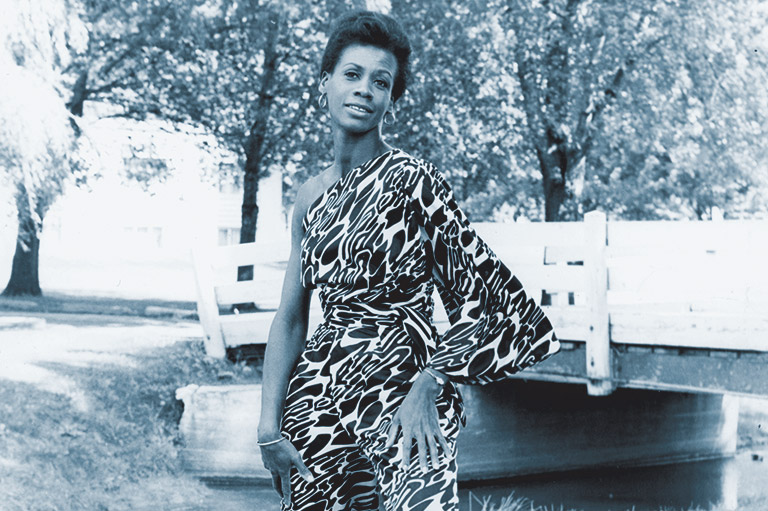

Although not many of them are seen on the track, women are critical partners in the chuckwagon racing initiative. Iris Glass, known as the Queen of the Chucks, once said, “They just don’t run the wagons without the women.” Born to a chuckwagon-driver father in 1924, Glass grew up to become the matriarch of a multi-generational chuckwagon-racing family. She contributed so much to the sport that the Calgary Stampede named her the parade grand marshal in 2003.

Women can be found working in the barns, feeding the crews, training and tending the horses, driving the trucks and trailers, fostering sponsor relationships, and performing myriad other tasks.

The only woman to compete as a Calgary Stampede outrider was May Gorst, who raced for three years beginning in 1979. The first woman to drive a chuckwagon professionally was Amber L’Heureux of Glaslyn, Saskatchewan. L’Heureux was the Canadian Professional Chuckwagon Association’s 2019 rookie of the year, and she continues to race today.

Chewing the Dust

Integral to the chuckwagon outfit are the outriders. Originally known as “helpers,” their roles derive from readying a working range chuckwagon. For almost ninety years, Calgary races featured four outriders per outfit: the lead man, who steadied the lead horses at the race’s start; the stove man, who tossed the stove into the wagon’s rear; and the two peg men, who tossed the tent pegs, attached to the canvas fly, into the wagon. In 2011, the two peg men and their horses were eliminated from Calgary Stampede races.

Today, when the klaxon roars, the lead man skirts out of the way of the oncoming chuckwagon, and the stove man throws in the stove. With the initial jobs done, each outrider grabs his horse’s saddle horn, jumps into the saddle without using the stirrups, and chases his chuckwagon around the barrels and racetrack. Chewing the wagon’s dust, outriders need to be within two hundred feet (approximately sixty-one metres) of their wagon at the finish line to avoid penalties; originally, that distance was just seventy-five feet, or about twenty-three metres. Outriders reflect the team nature of the sport. Many times, an outrider’s error has cost a driver day money — the cash prize awarded to the outfit with the fastest time of the night — or, worse, a championship.

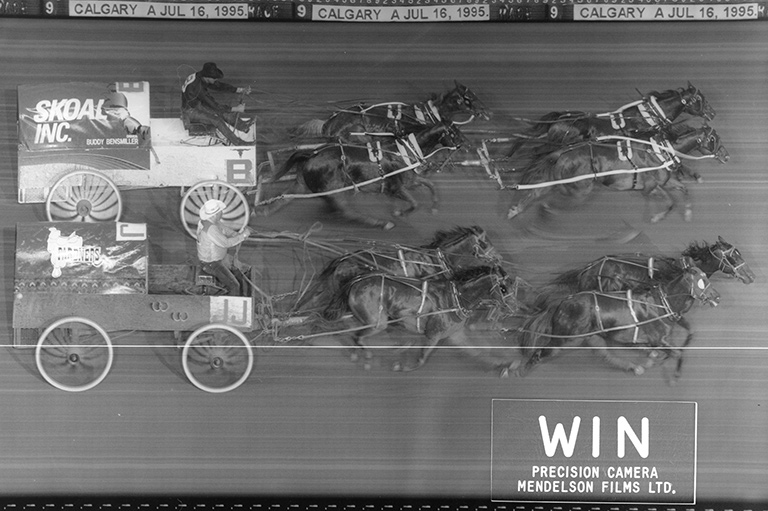

Photo Finish

It was literally a photo finish in the Calgary Stampede’s 1995 Rangeland Derby championship. The race between Ward Willard and Buddy Bensmiller was too close for announcer Joe Carbury to call, so the judges, cowboys, and crowd waited while the finishing photo was developed in the grandstand’s bowels. Willard won the race, his first and only Rangeland Derby championship, by three one-hundredths of a second — just the length of a horse’s head.

Calgary Stampede races were measured in tenths of a second until 1961, when two outfits tied. From 1962 onwards, races were timed in one-hundredths of a second, and in 2012 Troy Dorchester won the Calgary Stampede by one one-hundredth of a second — the smallest margin ever.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement