Racing Against the Best

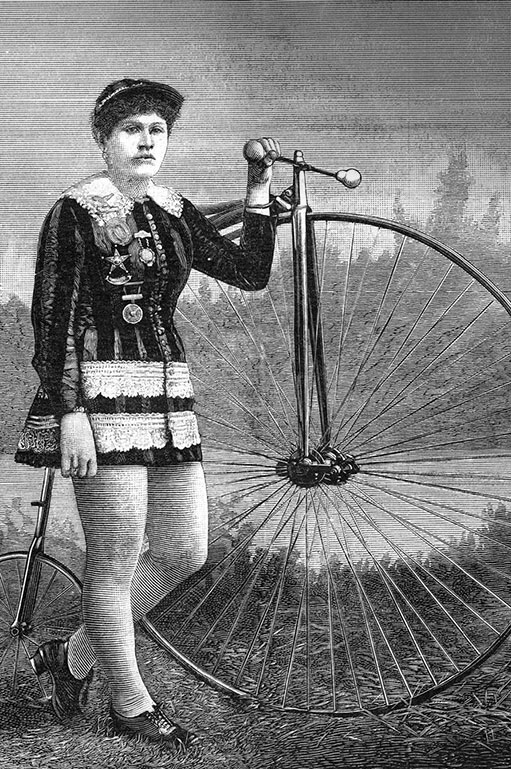

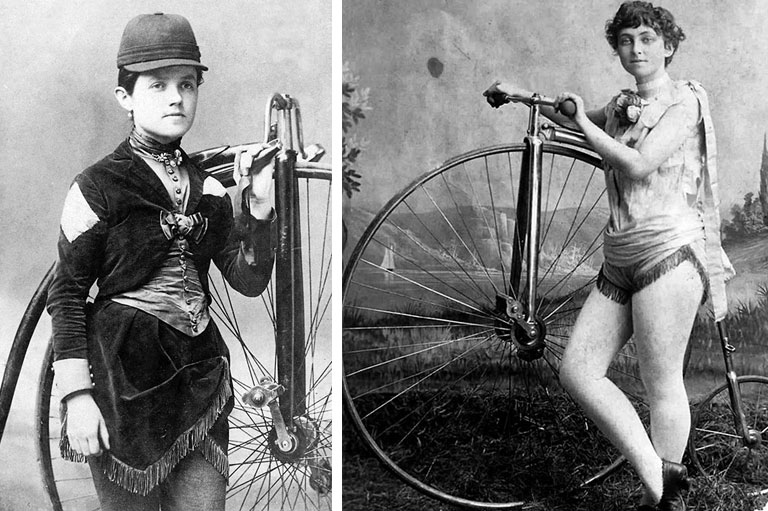

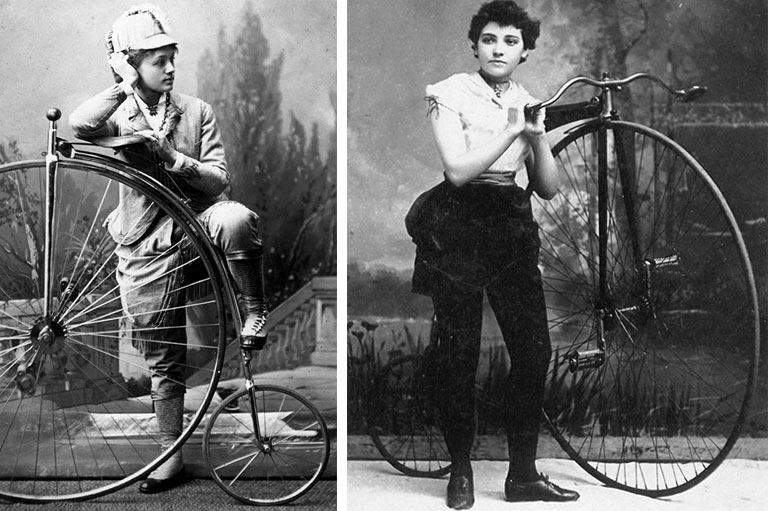

Louise Armaindo was one of Canada’s first women professional athletes and was also a celebrated performer. Hailing from the Montreal area, she earned her reputation first as a strongwoman and trapeze artist in Chicago and then as a high-wheel bicycle racer who competed on tracks across America beginning in the 1880s.

For the most part Armaindo’s only serious challengers were men, whom she often bested in races that took place for several hours per day over consecutive days. The events drew thousands of spectators — including large numbers of women who turned out to see Armaindo — as well as press coverage and trackside betting.

In Muscle on Wheels: Louise Armaindo and the High-Wheel Racers of Nineteenth-Century America, sports historian M. Ann Hall shows that, even in the Victorian era, women participated in bicycle racing, including on the high-wheel bicycles that became the standard machine in the 1870s.

Many of these women displayed enough talent and athletic ability to earn a living while competing in colourful costumes that contributed to the entertainment and occasionally attracted derision. But it’s Armaindo’s story — and her ability to compete against the top men racers such as John Prince, William Woodside, and William Morgan — that makes her a fitting central character for Hall’s book.

Louise Armaindo continued to pit her skills against a handful of professional riders. Although the rewards were primarily financial, she was a competitor who enjoyed beating her male rivals, especially when the stakes were for the “Championship of America.”

In September 1882 she again met John Prince at the Polo Grounds in New York where she received a three-mile handicap in a twenty-five-mile race. Prince wore white tights, his arms bare, and on his head was a black jockey cap. Louise was dressed in a crimson jacket trimmed with silver lace, red trunks, red-and-white stockings, heavy walking shoes, and a scarlet silk cap. A diamond crescent glittered at her throat. There were some five hundred spectators in the grandstand, many of whom were women wearing Louise’s crimson colours.

Prince rode a fifty-four-inch Yale machine; Armaindo’s was the same, but it had a fifty-one-inch wheel. Prince took the lead from the start and steadily increased the distance between them, slowly making up the three-mile handicap. Louise worked her pedals “like the cranks of a locomotive,” and, with perspiration running down her face, it was clear that she was overdressed for the occasion.

Near the end, the crowd cheered enthusiastically in support of Louise, and the women waved their handkerchiefs. It was all to no avail because Prince passed her on the second lap of the last mile, winning the race by eighty-four seconds. It was a slow race since they were some eighteen minutes behind the record.

Tom Eck was not only Louise’s official manager and agent but also her partner and probable lover. In press reports as early as 1879, Tom was often referred to as Louise’s husband. However, no record was found of an official marriage between the two. It is also clear that they were business partners because they needed each other to earn money. It was Tom’s job to find her opponents and races, and to promote her growing reputation. He was also in charge of her training.

Occasionally, when no challenger could be found, he was forced to go up against Louise himself, to his inevitable defeat, which brought about charges of “hippodroming” or predetermining the outcome. After watching Tom and Louise race at a meet in Springfield, Massachusetts, one commentator complained, “If it is necessary to exhibit female riders to please a certain element in a crowd a half-mile dash is enough to serve the purpose.”

When there were no human riders available to challenge, Tom pitted Louise against a horse. All this put her in superb condition for the first serious test of her racing career. She would race against the leading male professionals without the advantage of a handicap.

Supremely confident, Louise Armaindo was going to try to break all short-distance records.

A reporter was watching Louise train and ride at the Chicago Natatorium in preparation for these races. Suddenly wheeling up to the visitor, Louise stopped, dismounted, and inquired, “How do you like me for ze expert bicyclienne?” “Oh, pretty well,” said the reporter, who attempted to transcribe her accent, “but you are almost too fat to be in good racing condition.” “Too fat! Too fat!” Louise screamed. “You of my leg feel! You ze muscle find and not ze fat!” She was an incredibly strong and superbly fit young woman, and she was about to prove it.

For six days in May 1883, William M. Woodside, William J. Morgan, and Louise Armaindo took part in the first real long-distance race for the U.S. championship. On a makeshift track laid out in the Battery D Armory on Chicago’s lakefront, with thirteen laps to the mile, they raced twelve hours a day, beginning at eleven in the morning and ending at eleven at night. They took breaks whenever they wished, but to do so meant that someone else would move ahead.

At the end of the first day, there was little separating the three riders. After the fourth day, Armaindo had moved ahead slightly after completing 561 miles to Morgan’s 559 and Woodside’s 558.

“For persistent attention to the business and continuous staying qualities,” wrote an awed reporter, “Louise Armaindo, the French girl, takes the souvenir.” Louise increased her lead over the last two days and closed the seventy-two-hour race at 843 miles.

Morgan came second after 820 miles, whereas Woodside had seriously fallen back, finishing at only 723 miles. Her post-race commentary was interesting: “No one can have any idea how I had to punish myself to hold to the end; but I had determined to beat those two men, and I did it.” She also commented on the presence of a great many women in the audience, who encouraged her with kind words and rapt attention. For Louise, that was one of the best things about the race.

The contest was a huge success, with some two thousand people visiting the armory nightly to watch the exciting action. Newspapers praised Louise’s win against the best riders of Ireland and Canada, often failing to mention that she too was from Canada.

An editorial in an Arizona paper, willing to concede bigger hearts and clearer brains to the “gentler sex,” said it would also have to accept their stronger limbs and greater endurance. “Don’t let us glorify the males any more at the expense of the females,” said the writer, but “let us place them in the same niche to which their virtues and their limb power entitles them.”

In addition to her share of the gate, Louise was awarded two valuable badges for her victory. One represented professional honours and was valued at three hundred dollars. It was in the shape of a wheel suspended by chains from two bars that were appropriately engraved. The other, given to her by admirers, was a magnificent five-point gold star valued at five hundred dollars. In the centre was an engraving of a woman cyclist surrounded by five diamonds.

Woodside was crushed. Admitting to a “breakdown” towards the end of the race, he was far from convinced that the “plucky little” Louise was the better rider, and he wanted another chance to prove it. He immediately issued a challenge: “I therefore hereby challenge her to ride a similar contest for $100 to $1000 a side, and the championship of America, the race to be open to all comers who will deposit a similar amount. If Mademoiselle does not care to ride so long a distance again, I will give her five miles start in fifty, or ten in one hundred, and race for $100 to $500 on any track not less than eight laps to the mile.”

Louise did not ignore Woodside’s challenge, but she had her own agenda and was not about to get sidetracked. A week after the race in Chicago, she again defeated Morgan and Woodside during a 120-mile race in Janesville, Wisconsin, riding forty miles each evening on a track of twenty-three laps to the mile. Louise took the lead from the beginning and won by three laps. …

Prince, Morgan, and Woodside were among the best professional high-wheel racers in the United States, and perhaps elsewhere. Physically they were considerably bigger and taller than Louise, whose height was variously reported at between five feet one and five feet four. Shorter in stature, she was well-muscled, with her weight usually stated as around 130 pounds. Taller racers obviously had an advantage because they could use a bicycle with a larger front wheel, but a shorter rival could nullify this advantage with quicker, more efficient pedalling. …

The Armaindo-Morgan-Woodside racing trio was a remarkably popular entertainment attraction, the more so because of Louise. There was no question that more “ladies” attended the races than would be the case if only males were racing. It was also important to keep these contests as exciting and close as possible, and Woodside, probably the speedier racer, agreed to give the other two a handicap.

Their next race was in Milwaukee’s Exposition Building, where a new board track had been constructed. Tom Eck declared it to be the fastest track in America — faster than those in the Boston Casino or the Chicago Exposition — and also the safest, at eight laps to the mile with easier turns and a smoother floor surface. Over the six-day, three-hours-per-night race, Woodside agreed to give Morgan a twelve-mile start and Louise thirty miles, both to be distributed over the six days.

The event turned out to be the best and most exciting racing so far witnessed in the Northwest. Louise declared she was planning to go for speed rather than endurance because of only a three-hour ride each night. Increasingly boastful and supremely confident, she was also going to try to break all short-distance records. By the second day, Louise was in front, but Morgan and Woodside were catching up. Some five thousand free tickets were made available to children, who began filling up the building, along with an increasing number of women spectators.

Louise was tireless and clearly the crowd favourite: “When the plucky little woman would urge her noiseless steed and flash past either of her male competitors, the spectators loudly testified their appreciation,” wrote the Milwaukee Sentinel.

They were even more appreciative when she changed her costume to a gaudy ensemble of pink silk tights, bronze boots, white undervest, wine-coloured jacket, and red-white-and-blue jockey cap. On the last day, Morgan and Woodside were hampered with problems with their bicycles, leaving Louise the clear winner with 294 miles to Morgan’s 285 and Woodside’s 277.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!