Intrepid adventurer

As Mark Bourrie makes clear in his latest book, Pierre-Esprit Radisson was much more than an explorer and a trader. Born in France circa 1636, he arrived in 1651 at Trois-Rivières, in what is now Quebec, and was soon afterwards captured by Mohawk (Iroquois) warriors. Adopted into a powerful Mohawk family, Radisson travelled as a member of a raiding party and learned Indigenous languages.

After defecting to the Dutch in North America and then returning to Trois-Rivières, he made trips west with Jesuit priests and Iroquois parties. In 1658 Radisson departed on the first of his travels with his brother-in-law Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers, during which they explored the Great Lakes and Ottawa River regions in search of furs. Their plans to journey to Hudson Bay were thwarted until 1668, when they set sail from England with the backing of Prince Rupert and the wealthy merchants who would form the Hudson’s Bay Company.

In Bush Runner: The Adventures of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, Bourrie draws from Radisson’s own journals and details his many escapades — and setbacks — including his capture by pirates and several years stuck in London, England, awaiting the chance to voyage to Hudson Bay. Living through plague, war with Holland, and the Great Fire — after which vindictive mobs sought out foreigners for retribution — Radisson survived what Bourrie calls the worst conditions London would see until the Second World War. Meanwhile, the English granted Radisson’s brother-in-law the nickname “Gooseberry,” a loose translation of his name Groseilliers.

To the Bay

King Charles II leased the small two-mast ship the Eaglet to Prince Rupert and his fellow investors, while the dependable Captain Gillam of Boston was already outfitting the Nonsuch. Rupert issued orders to the captains of both ships, telling them of the importance of their mission and warning them to “use the said Mr. Gooseberry and Mr. Radisson with all manner of civility and to take care that all your company do bear a particular respect unto them, they being the persons upon whose credit we have undertaken this expedition.” The expedition was also given orders to look for a Northwest Passage to the Pacific Ocean, which, if found, would have made all of the investors spectacularly rich.

After a sumptuous dinner in the spring of 1668 — one of many that lubricated negotiations for the financing of the expedition — the eighteen investors, who included the Duke of Albemarle, several earls, and some of the richest men in the city of London, headed to the wharf to catch a barge to Gravesend to see Radisson and the Eaglet off. The Nonsuch had already sailed and would make it to Hudson Bay carrying Groseilliers.

But the Eaglet was no seabird. Somewhere northeast of Ireland, she was caught in a wicked six-hour storm in waves so high that the men aboard were sure she was about to capsize. Even with all her sails down, the wind pushed so hard against the rigging that the Eaglet lay almost sideways in the grey, churning water. Fighting desperately to save her, the Eaglet’s crew chopped down her main mast and pushed it overboard into the roiling, cold sea. With the main mast gone and the storm abating, the crew was able to regain control of the Eaglet, but she was in no shape to keep going westward, so they raised sails on the surviving small mast and limped back to Plymouth.

In a bit of disinformation, the London Gazette officially reported in its August 13, 1668, edition: “Plymouth, Aug. 7. On Wednesday last (Aug. 5) came in the Eagle[sic]. Ketch, having in her way for Newfound-land been severely handled by storm, in which she spent her main Mast, and with some difficulty put back to refit.” Once again, Radisson was stuck in England.

Groseilliers and the tougher Nonsuch skirted the sea ice and arrived in August at the mouth of the Nelson River after a four-month journey through the bleak, grey waters of the North Atlantic and Hudson Bay. As they sailed south along the coastline, it became clear to the English sailors that Groseilliers, despite the stories he and Radisson told, had no idea about the geography of Hudson Bay. The navigators looked for the mouth of the river where the explorer Thomas Button had built a house in 1613, and somehow they found the ruins at the outlet of the Nelson River. This was a big estuary surrounded by hills covered with scrubby pine forests that was dangerous to approach because of sandbars and strong tides that left miles of mudflats when low, but it was the seaport of one of the longest canoe routes to the west.

Radisson left in the dead of the brutal winter to trade with the Cree, hundreds of kilometres away.

The Cree quickly found the ship and traded for the hardware and cloth that she carried. Groseilliers had also brought some wampum with him and used it to cement trading alliances with the Cree leadership. It was too late to return to England that year, so the crew of the Nonsuch built a fort, which they named after the king, and settled in for a very long, cold winter. …

Because Gillam kept them busy and well-fed, surprisingly few men died that winter. In the spring, they were able to contact the Cree to let them know the Nonsuch was still in business. It took most of the next summer for ice to clear from the bay, so Groseilliers and his companions got in another trading season before finally getting past Hudson Strait and heading home in August 1669.

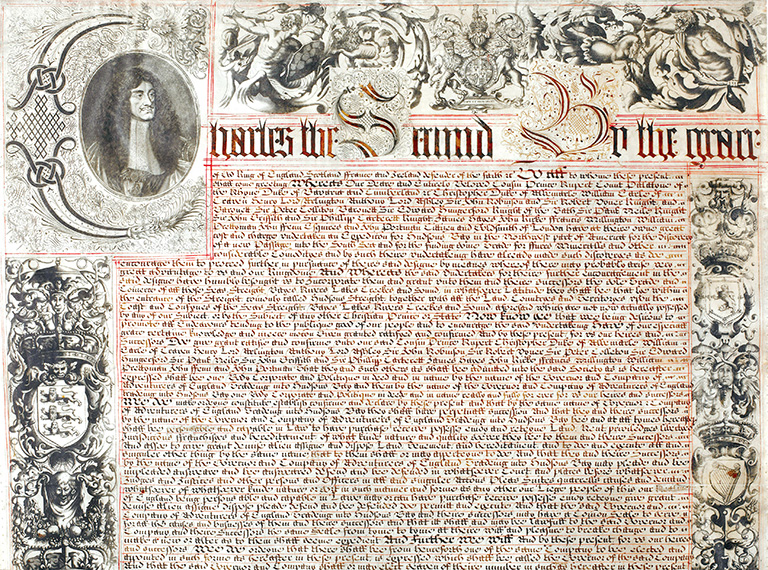

The trip was very profitable for the investors, and not just because of the payoff from the sale of furs. Charles II was so impressed when Rupert told him of the expedition’s success that he very generously granted the investors a trading monopoly in Hudson Bay, along with half of what’s now Canada and part of North and South Dakota: that is, all the land in the drainage basin of the rivers flowing into Hudson Bay. None of this was his to give, of course, and at the time no one saw the grant as anything more than a gentle legal warning against French intrusion in the new English trade. …

Charles probably did not expect the Hudson’s Bay Company charter to cause a rift with France, and he certainly had no idea he was giving away almost half a continent and many billions of dollars worth of resources. He was also illegally handing the lands of several First Nations over to corporate control. Two centuries later, the grant would be used as legal justification for Canadian expansion into the prairies, with all the disease, displacement, and social destruction that followed for the First Nations who lived there.

For now, the focus was on building and paying for ships and gathering what was needed to build forts — “factories” in Hudson’s Bay Company lingo — along the shore of that vast inland sea. Like the French in Quebec, the company had no desire to colonize the land holdings that it laid claim to. All it wanted was furs, at the cheapest price possible. And no competition. …

In May 1670, the new Prince Rupert, skippered by the ubiquitous Gillam, left England carrying Groseilliers. Radisson went to the bay on the Wivenhoe, along with an odd character named Charles Bailey, whose previous residences included Virginia, several London jails, and the Tower of London. … Bailey was something of an organizational genius with a talent for business. When the Wivenhoe arrived in Hudson Bay, it was Bailey, acting as a local governor, who chose the sites of the company’s forts and ran the trade.

Radisson wanted to go into James Bay to find a big river that would take him to Lake Superior and back to the upper lakes, where he and Groseilliers had made so much money a decade earlier. Radisson claimed an English canoe flotilla could reach Green Bay on Lake Michigan in a week, which is absurd. He also told the English that it was only 150 miles (240 kilometres) from the south end of Lake Michigan to the Gulf of Mexico. Luckily for Radisson, his geography was never tested. …

Bailey wanted to trade from the shore and couldn’t care less where the rivers came from, so long as the Cree could find his factories. The main fort was to be at the mouth of the Nelson River, a fantastic choice, since it lay at the end of the Saskatchewan River-Lake Winnipeg canoe route. At the last minute, the 1670 expedition left the Nelson for the nearby mouth of the Nemisco, which they renamed the Rupert River.

Bailey had brought bricks and wood to build a comfortable fort. His men loved him because he looked after them, bringing barrels of beer on the trip and the ingredients to make more, and giving them time off to hunt ducks and caribou. At times, he even got along with Radisson, to whom he gave a prized possession: a fine, expensive manuscript atlas. The old jailbird was nevertheless determined to make Radisson redundant. Bailey took over the negotiations with the Cree, even though he knew nothing about them, at least at first. …

Rather recklessly, Radisson left in the dead of the brutal, dark winter to trade with Cree at the mouth of the Moose River, hundreds of kilometres away at the bottom of James Bay. Knowing they would be short of food, he brought dried peas, for which the Cree were willing to pay dearly. The Cree, at what’s now Moose Factory, promised Radisson they would come north to the Rupert River in the spring. In their reports to England, Bailey and his second-in-command, Thomas Gorst, gave Radisson no credit for any of this.

In the summer of 1671, Bailey and Gorst explored and mapped James Bay before leaving for home on July 24 with the ships’ holds stuffed with furs worth one pound sterling for every two pounds of fur. For the first time, Radisson and Groseilliers found themselves shunted aside. They were now tourists on their own expedition, foreigners among the xenophobic English, Catholics among Protestants. They didn’t have enough money to have a stake in the ownership of the company.

Now the English were becoming experts in cold-weather survival and in diplomacy with the First Nations. The two Frenchmen had come up with a great idea, but once they shared it, it was no longer theirs. When they got back to England, they were given a measly bonus of five pounds, while the Duke of York got a full share of the company, worth three hundred pounds, just because he was next in line for the throne. The duke’s share also came with the promise of a big dividend.

At about the same time, the company’s leaders decided to enforce a rule against its employees trading privately with the First Nations. This had been the real gravy for the two Frenchmen, who, between them, had made £162 by moonlighting with their own stock of trade goods, diverting furs that would otherwise have gone to the company. This was far more than their base salary of £50 a year. Even with the profits of private trading, they were making nowhere near the money they’d pulled in from their Lake Superior expedition to the Sioux and the Cree.

Radisson was no longer the centre of attention or the go-to man on Arctic exploration.

Radisson and Groseilliers stayed in London to help put together a third expedition to Hudson Bay, but their pay, and even the now-official title of “Captain Gooseberry,” did not keep them happy as they watched the Hudson’s Bay Company investors making a fifty-per-cent return on their investments. In Quebec, they dealt with just one greedy governor. With the English scheme, there were the calloused hands of sailors and the soft hands of eighteen investors waiting for gold.

Radisson may well have seethed with jealousy when he saw that it was the English sea captains, and not him, who were invited by the Royal Society to give lectures on their Hudson Bay adventures. Radisson was no longer the centre of attention or the go-to man on Arctic exploration, which must have really hurt. Soon, the company would be able to run its Hudson Bay trade without him.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!