The Reel Story

If you’re in Toronto in early September, expect to see throngs of would-be celebrity-sighters gathered at the entrances of such swanky hotels as The Ritz-Carlton and Shangri-La, as well as venues like Roy Thomson Hall and TIFF Bell Lightbox. It’s the time of year when thousands of movie fans descend on Canada’s largest city to attend the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

Over the past half-century, TIFF has become one of the world’s premier showcases for movie releases — its People’s Choice Award, based on audience voting, has become a bellwether for Academy Award winners — and “a massively important” film festival, according to veteran Canadian comedic actor Martin Short (see “Reel Men”). In Short’s view, TIFF’s presence in Toronto further underscores the city as a film capital with the “greatest camerapeople, the greatest sound people, the greatest set designers” working in Hollywood’s major studios or when Hollywood comes to Canada to make movies at a lower cost.

Los Angeles Times film editor Joshua Rothkopf — who attended the festival for nearly 20 years, beginning in 2002 — says he appreciates how TIFF “functions as a great one-stop shop,” featuring films from other international festivals, such as the Cannes Film Festival. And Toronto film critic Adam Nayman, who lectures on cinema at the University of Toronto and Toronto Metropolitan University, says TIFF was created to get Hollywood to send its “stars and movies for publicity.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Beyond coming to Toronto to showcase its work, Hollywood has come to Canada for decades to make movies. Watch a Christmas movie on the Lifetime or Hallmark channel over the holiday season, and there’s a good chance it was shot in Canada. Some of the biggest box-office and Academy Award-winning movies over the past 30 years — including The Shape of Water and parts of Titanic and Chicago — have been filmed in “Hollywood North,” a title principally applied to Toronto and Vancouver but extended to such other cities as Montreal, Winnipeg and Halifax.

Still, Canada’s connection to Hollywood reaches even further back. From the star power of silent-film diva Mary Pickford to the technology developed in the early days of the National Film Board of Canada to the sound, special effects and film editing that all converge to make movie magic, Canada has been Hollywood’s best supporting actor since Tinseltown’s inception.

Movie stars

More than a century ago, Canadians helped establish Hollywood as the planet’s movie capital, and a key builder was an actress born Gladys Louise Smith on April 8, 1892, in Toronto. She later took the stage name Mary Pickford.

Ironically dubbed “America’s Sweetheart” during the silent-film era, Pickford became one of cinema’s first celebrities in front of the camera. She began her acting career onstage at age seven in her hometown, and not long after, she appeared on Broadway. It was there, while co-starring in The Warrens of Virginia in 1907 with director and producer Cecil B. DeMille (whose brother, William, wrote the play), she assumed her stage name. But it would be onscreen and off where Pickford would make an indelible mark on movie history and become one of the most recognizable women in the world.

In 1916, she signed a deal with Adolph Zukor, a cofounder of Paramount Pictures, which made her the first actress to enter a $1-million contract. Two years later, Pickford, along with her then-future-husband Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin and pioneering director D.W. Griffith, formed United Artists Corporation. In 1927, she and Fairbanks were among the 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), which bestows the Academy Awards.

Pickford starred in 52 feature films during her 55-year career and received two Oscars: Best Actress for the 1929 drama Coquette, and an honorary Academy Award in 1975 “in recognition of her unique contributions to the film industry and the development of film as an artistic medium.” Pickford, who died in Santa Monica on May 29, 1979, at age 87, was one of three Canadian actresses who won consecutive Oscars in the early 1930s.

The second, Norma Shearer, born in Montreal on Aug. 11, 1902, was named Best Actress for her role in the 1930 film The Divorcee. Following Shearer’s win, Marie Dressler — born Leila Marie Koerber on Nov. 9, 1868, in Cobourg, Ont. — received the Best Actress Oscar in 1931 for the comedy Min and Bill. Shearer was also nominated in that category and would receive three more lead-actress nominations in the 1930s. No other Canadian women would receive an acting Oscar until 1994, when Winnipeg-born Anna Paquin won Best Supporting Actress — at the age of 11 in her acting debut in The Piano.

Advertisement

Innovation and technology

If Canadians have been enjoying the spotlight for the past century or so, we have this country’s innovative minds to thank for shining it. David Sobel, a Toronto-based historian and former Ontario civil servant, created a website called The Moving Past that highlights 15 of the more than 1,000 Canadian films made between 1918 and 1929. That large volume of early cinematic work was driven by both the Ontario Motion Picture Bureau — the world’s first state-funded film production company, established by the Ontario government in 1917 — and the Exhibits and Publicity Bureau, formed by the federal government a year later, eventually becoming the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) in 1941 (see “Well-documented contribution” ).

The federally funded films were mainly produced to promote Canada as a tourism destination, and those produced by Ontario focused on educational work for groups like farmers or factory workers. But the camera operators, set designers, editors and writers involved became much in demand for the skills they amassed while shooting films “in steady, relatively well-paid jobs,” explains Sobel. Crews on sets in the early days of Hollywood, meanwhile, were without a job after a film was shot — not unlike today, he says. “The technical know-how that was developed early on through these government motion picture bureaus — that didn’t exist in the United States — made a significant impact” on Hollywood’s nascent film industry, he says.

Although he didn’t work for either the Canadian or Ontario film bureau, Winnipeg-born Osmond Borradaile was a pioneer in Tinseltown. A consequential cinematographer, he worked on silent movies with such legends as Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson and Lillian Gish, and then “talkies” with Cecil B. DeMille. Among Borradaile’s notable achievements was filming the aerial sequences for eccentric American billionaire Howard Hughes’ 1930 film, Hell’s Angels, in which Hughes — the film’s producer and director — served as the pilot for the shoot.

Borradaile was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1982 and died in West Vancouver in 1999 at the age of 100.

Scene and heard

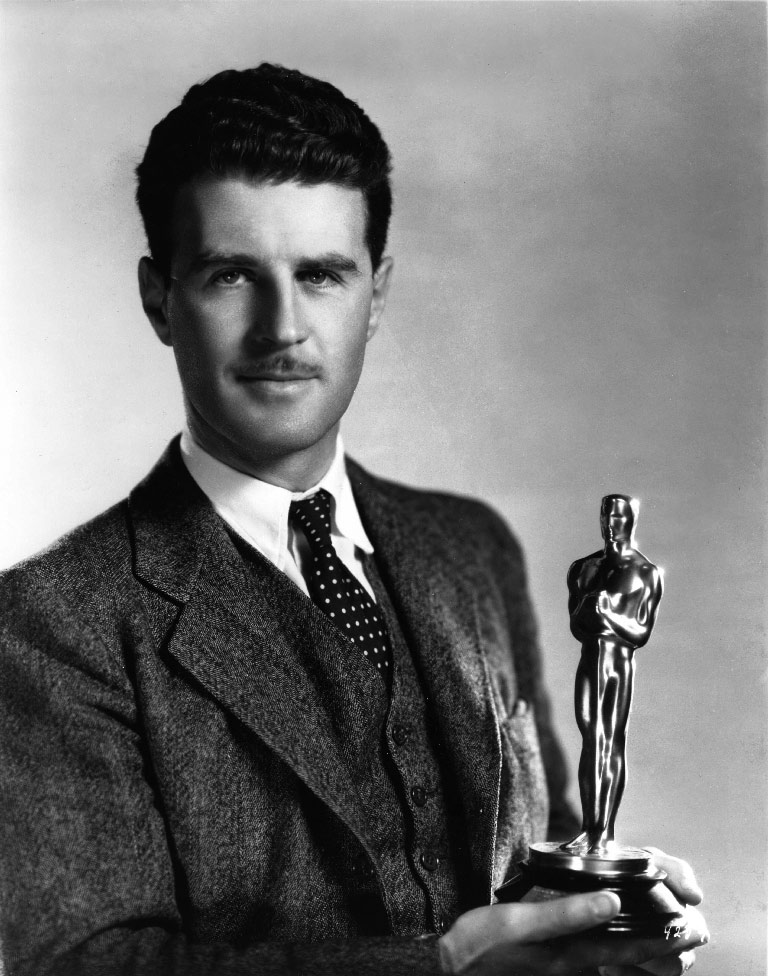

As early as the 1920s, Douglas Shearer (brother of actress Norma) was making movies heard. Born on Nov. 17, 1899, in Westmount, Que., he headed to California in 1923, where he joined Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios. He was appointed head of the sound department when the talkies arrived in 1928. It was a smart move.

Between 1929 and 1951, Shearer won seven Academy Awards — two for special effects and five for sound — and was nominated for 14 more. Douglas’s first Oscar, for Best Sound Recording for The Big House, was in 1931, the same year Norma won hers and the only time in Academy Award history when a brother and sister received Oscars on the same night.

Shearer and the MGM Studio Sound Department also received an Award of Merit, in the form of an Oscar statuette, in 1936, for the development of a sound-recording system. In The Film Encyclopedia, Ephraim Katz writes that during Shearer’s “more than 40 years with MGM, he contributed more than any other man in Hollywood to the perfection of motion picture sound.”

On the music side, Toronto-born Howard Shore shines in Hollywood. His work on two installments of the Lord of the Rings trilogy won him three Academy Awards: one for Best Original Song and two for Best Original Score, making him the first Canadian to win two Oscars in that category. He is, according to Rothkopf of the Los Angeles Times, “one of the few composers who has an immediately appreciable style, especially the way he uses chords.”

Canadians have proven their worth on the post-production side, too, with three Academy Awards for film editing, including James Cameron for Titanic and Toronto-born Ralph E. Winters; the latter took home two Oscars — his last for the epic 1959 film Ben-Hur, which won an unprecedented 11 trophies. For Best Production Design, formerly known as art design, Canadians have won 13 Academy Awards, with seven going to Victoria-born art director Richard Day from 1936 to 1955, when he won Oscars for the classics How Green Was My Valley, A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, among others.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Celebrated directors

In the mid-1970s, Toronto became the hub of Canadian feature-film production. This was thanks in large part to a capital cost allowance, introduced in 1974, allowing producers to deduct all of their investment in a Canadian movie and defer taxes until profits were earned. “But so much of what ended up getting made ostensibly to resist American dominance were Canadian knockoffs of American movies,” says Nayman, who has written about filmmakers including David Cronenberg for The New Yorker. “Is this because the filmmakers of the tax-shelter period were so unimaginative and mercenary that they just copied American movies in the hope of making movies and a return on investment — or is it that it’s really hard to say what Canadian identity is in the first place?”

Rothkopf remembers growing up on New York’s Long Island when “pop culture was dominated by Canadians.” His favourite movie as a 14-year-old was the 1985 time-travelling classic, Back to the Future, starring Canada’s Michael J. Fox, who is not only a five-time Emmy Award winner but also the recipient of a Governor General’s Performing Arts Award and an honorary Oscar for his humanitarian work.

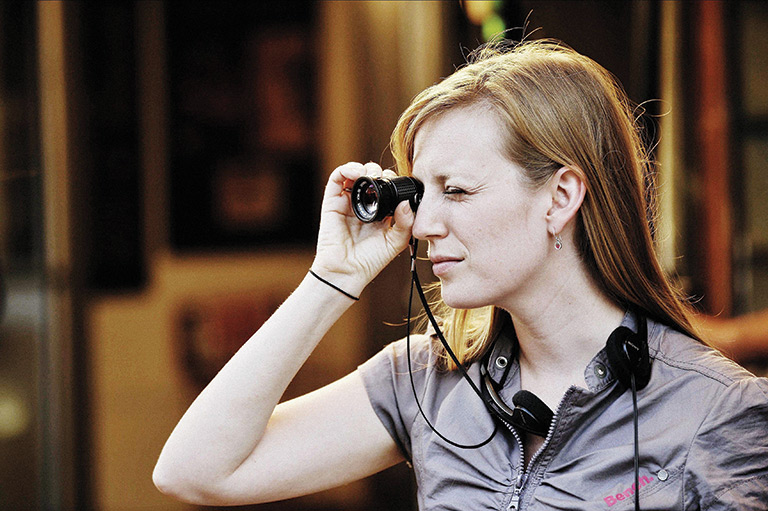

“When my tastes grew and I started getting into art cinema and serious movies, filmmakers like Atom Egoyan and David Cronenberg — and maybe most of all, Sarah Polley — were central to my understanding of what serious art was,” says Rothkopf, a former senior movies editor at Entertainment Weekly. He credits Polley’s deeply personal family account, Stories We Tell, produced by the NFB, with “expanding what we think of as documentary.” Rothkopf was the chair of the New York Film Critics Circle when it recognized the non-fiction film as the best documentary in 2013.

In Rothkopf’s opinion, Quebec has also produced two key filmmakers who have made an indelible mark on Hollywood’s cinematic history. With his Oscar-winning 2013 film, Dallas Buyers Club, and the first season of the HBO series Big Little Lies, which he directed, the late Jean-Marc Vallée was “a player and shaper of culture — someone who could channel commercial instincts into something that had a brain,” says Rothkopf. He adds that Academy Award-nominated director Denis Villeneuve — whose Dune parts one and two have earned more than US$1.1 billion at the box office — “is the great hope of Hollywood filmmaking. He’s a big-budget filmmaker who has a real sensibility.”

According to Nayman, though, Villeneuve and Vallée were “only successful in the States by evacuating any Québécois identity and working in English. Even the French-Canadian filmmakers who succeed are the ones who can camouflage their films as non-French Canadian and work in English.” He believes that, in some ways, Canada helped build Hollywood’s film industry “partially at its own expense,” resulting in domestic movies that “look cheaper with less famous people in them.

“I don’t think any national film industry has as fraught a relationship to Hollywood as we do because it’s not adversarial,” he continues. “We are supplicants to them.” He adds that “for directors who stayed, it’s a short list and a high bar. David Cronenberg is a great case study. But how many people can be David Cronenberg?”

Cronenberg lives in Toronto, as did the late Norman Jewison. The latter, who made such films as 1967’s Academy Award-winning In the Heat of the Night, enjoyed success working in the U.S. because he “saw how limited the opportunities were here,” says Nayman.

But that has resulted in a significant Canadian constellation within Hollywood’s galaxy populated by stars such as Martin Short. The actor views his compatriots as having made “an enormous impact” on Hollywood, “just based on the numbers,” referring to Canada’s population of 40 million compared with the more than 346 million who live in the U.S.

“Maybe it is about that we live between two major influences — the United States, the sexy sister, and England, the glamorous sister — and maybe we’re the sister who is way better looking than we think we are.”

Well-documented contribution

Some of the major inroads made in Hollywood regarding documentaries and animation have come from the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), the government-funded film-production agency.

In 1942, Churchill’s Island — a propaganda film chronicling the defence of Great Britain during the Second World War and narrated by Canadian actor Lorne Greene — became the first film to win an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Subject. The NFB would go on to receive more than 75 Oscar nominations and 12 Academy Awards, including an honorary Academy Award in 1988 “in recognition of its 50th anniversary and its dedicated commitment to originate artistic, creative and technological activity and excellence in every area of film making.”

About half of those Oscar nods and wins were for animation, a medium that the NFB helped develop for Hollywood. To boot, some of the first computer-generated animated films created with a SEL-840A general-purpose digital computer include filmmaker Peter Foldes’s 1974 Oscarnominated short, Hunger, produced by the NFB.

Beyond animation, the federal government’s film-production agency helped spawn a revolutionary format for screening movies. At Montreal’s Expo 67, the NFB presented In the Labyrinth, which used 35 mm and 70 mm film projected simultaneously on five screens. One of the filmmakers involved, Roman Kroitor, was a pioneer in Canada of cinéma-vérité and the creator of the software and hardware system called SANDDE, which designs hand-drawn stereoscopic 3D animation content. Kroitor went on to help develop IMAX large-format technology.

Before that, Kroitor had already appeared on the radar of one of the world’s top movie directors. A 1960 documentary short titled Universe, which he and colleague Colin Low made, caught the attention of Stanley Kubrick, who relied on it to create his vision of space in his 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick then cast Canadian Douglas Rain, the narrator in Universe, to voice the hostile HAL 9000 in his movie.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement