Great Moments in Canadian Hockey

For a time, hockey was an impossibly hard game to photograph. The slow chemical reactions of early cameras prevented photographers from capturing the fast on-ice action in the dimly lit hockey barns of the day. That’s why old-time play has mostly posed portraits and team shots, such as the 1893 Montreal AAA, the first Stanley Cup winners, and the Winnipeg Falcons, the first Olympic champions in 1920. Subjects back then rarely, if ever, smiled for the camera. One reason is because smiles are harder to hold than a serious look and any body movement would blur the photo — that is, until the 1930s, when high-speed film allowed shooters to capture arena hockey in every manner.

Among several examples here of modern photos that bring to life a shared moment of history in the making is Sidney Crosby’s Golden Goal at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Canada was playing with a 2-1 lead against the USA for the gold medal. With 24.4 seconds remaining, Zach Parise slid the tying goal under Roberto Luongo to force sudden-death overtime. Crosby had played an all-around solid game and scored three times in six tournament matches. More than seven minutes into OT, Crosby makes good on a Jarome Iginla pass, whipping a low shot through Ryan Miller’s pads.

Excited. Possessed. Fierce. A thousand words could not describe that bearing and look of conquest etched across Crosby’s face.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Barilko’s Clincher

The Bill Barilko goal, 75 years old in 2026, is still regarded as the Maple Leafs’ greatest Stanley Cup clincher. The Barilko story is of a marginal defenceman, reportedly facing a demotion, who seized the moment and overnight became a hockey hero — and soon, a legendary figure of tragedy. Defying the stay-at-home system of coach Joe Primeau, Barilko played up past Montreal’s offensive blue line and fired a riser beyond goalie Gerry McNeil for Toronto’s ninth Stanley Cup title in 1951. Barilko is captured in mid-air, eyeing the puck’s flight path into McNeil’s net.

Sadly, that summer, while returning from a fishing trip in northern Quebec, Barilko disappeared in a plane crash. His remains and those of pilot Dr. Henry Hudson weren’t discovered until 1962, the year the Maple Leafs won their next Stanley Cup.

Gretzky to Lemieux

So epic was this one puck pass at the 1987 Canada Cup, so monumental was its electrifying series winner and so famous are its two finishers that Canada’s breakout play today lives on in hockey vernacular with the conceit of its own proper nickname and a deep legacy in international play as “Gretzky to Lemieux.”

Canada and the Soviet Union were icing their deepest rosters in the tightly contested three-game series. Each had scored OT wins by identical 6-5 tallies and, now tied 5-5 with a minute left, world hockey supremacy was on tap — along with, naturally, those bragging rights. Canada struck with defenceman Larry Murphy playing decoy on right wing as Wayne Gretzky tore into the offensive zone with Mario Lemieux trailing. Only Igor Stelnov was back. Gretzky slipped the puck to the 21-year-old Lemieux, who lasered a wrister top shelf beyond Sergei Mylnikov. Pandemonium ensued at Hamilton’s Copps Coliseum — and everywhere else.

Orr Soars

By 1970, Bobby Orr, in his fourth NHL season with the Boston Bruins, had become a household name throughout the hockey world. What left a truly indelible mark was his moment of victory in scoring that year’s Stanley Cup winner. Orr is immortalized in black and white, arms outstretched, in full Marvel-superhero flight. His youthful face radiates sheer delight. The thrill of triumph, already in celebratory mode. The give-and-go play with linemate Derek Sanderson sent Orr into the crease area of St. Louis Blues goalie Glenn Hall. Orr entered that no man’s land and scored on the forehand as Blues defender Noel Picard hooked his stick blade around Orr’s left ankle. The illegal tactic propelled Orr skyward and into hockey history, cementing the Parry Sound, Ont., native’s preternatural speed and skill in hockey lore as the game’s greatest player. This image remains the sport’s most enduring and recognizable photograph.

Advertisement

A Greater Goal

Like many challenges in breaking the gender boundaries of sport, Jayna Hefford’s second-period goal in Canada’s 5-4 goldmedal win at the 2012 International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) Women’s World Championship and her play alongside captain Hayley Wickenheiser (who was parked at the doorstep of USA goalie Molly Schaus) has deep origins in the past. Its specialness — no greater, no less — draws on the sporting prowess of early heroines Hilda Ranscombe and the great Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld, plus more recently, Angela James and Cammi Granato, the first women of Hockey Hall of Fame status. Their cultural struggles throughout the evolution of women’s play have brought a brighter future where the collective athletic efforts of today’s stars, like Hefford, are finally being recognized as equal but different. Regrettably, it’s taken more than a century of defiance and game discrimination to reach the ultimate goals of a more inclusive, competitive world game and the promising success of the Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL).

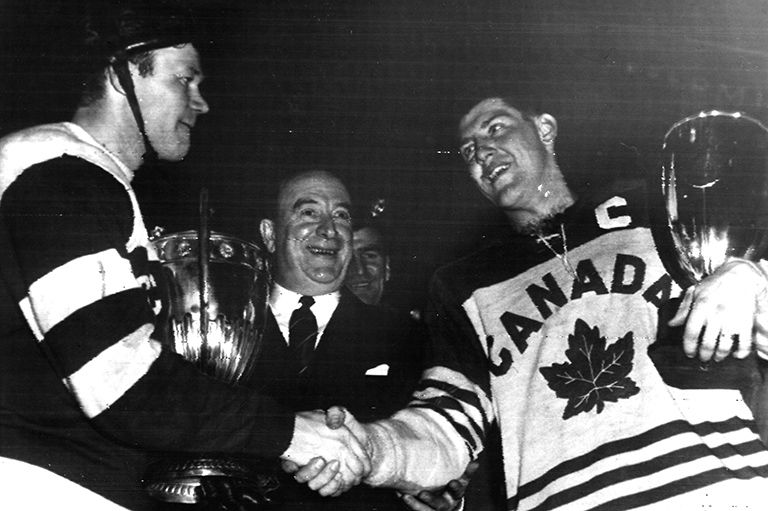

Top of the Worlds

Until 1954 happened, the World Championship typically meant a second-place finish for European and American teams to Canada’s gold medal. That winter in Stockholm, a crowd of 16,000 watched the Soviet Union outskate and outmuscle Canada, dismantling the East York Lyndhursts 7-2 to capture gold in their first superpower showdown. The defeat shocked Canada to its core, with front-page headlines and editorials everywhere.

The 1955 Worlds would be different. To exact revenge and restore national pride, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association chose the hard-charging Penticton Vees, led by the legendary Warwick brothers, forwards Grant, Bill and Dick. Accounts were settled in Canada’s 5-0 golden beatdown of the Soviets. The country had briefly regained world supremacy and its hockey mojo, as seen here with left winger Vsevolod Bobrov, IIHF vice-president Bunny Ahearne and defenceman George McAvoy. This moment ushered in the great Canada-Soviet rivalry, with the Soviets monopolizing play in a near-invincible reign until the USSR’s breakup in 1991.

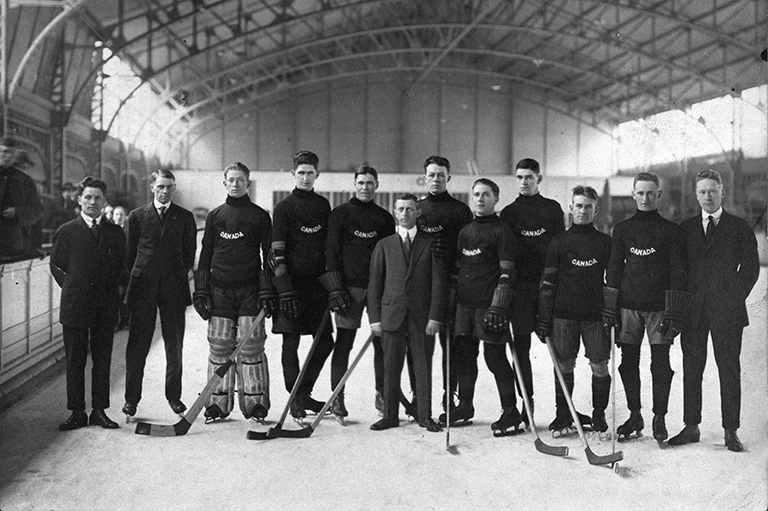

Going Global

Canada’s historic entrance in international play began with the Winnipeg Falcons in a demonstration tournament at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium. The Falcons, an unheralded squad of second- and third-generation Icelandic Canadians, crushed Czechoslovakia 15-0, USA 2-0 and Sweden 12-1. It didn’t matter that Canada competed light years ahead of the under-skilled Europeans in ice hockey; the Falcons became the first Olympic gold medallists and the first world champions. Their participation led to world hockey’s greater acceptance across Canada and in Europe. Awed by the Canadians’ speedy play, according to the coverage in the Hamilton Spectator, some speculated that forward Mike Goodman’s skates “had a motor concealed in them somewhere.”

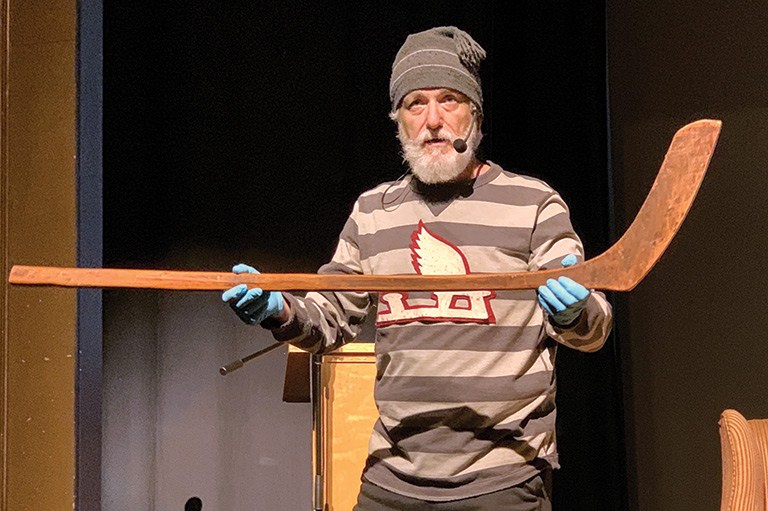

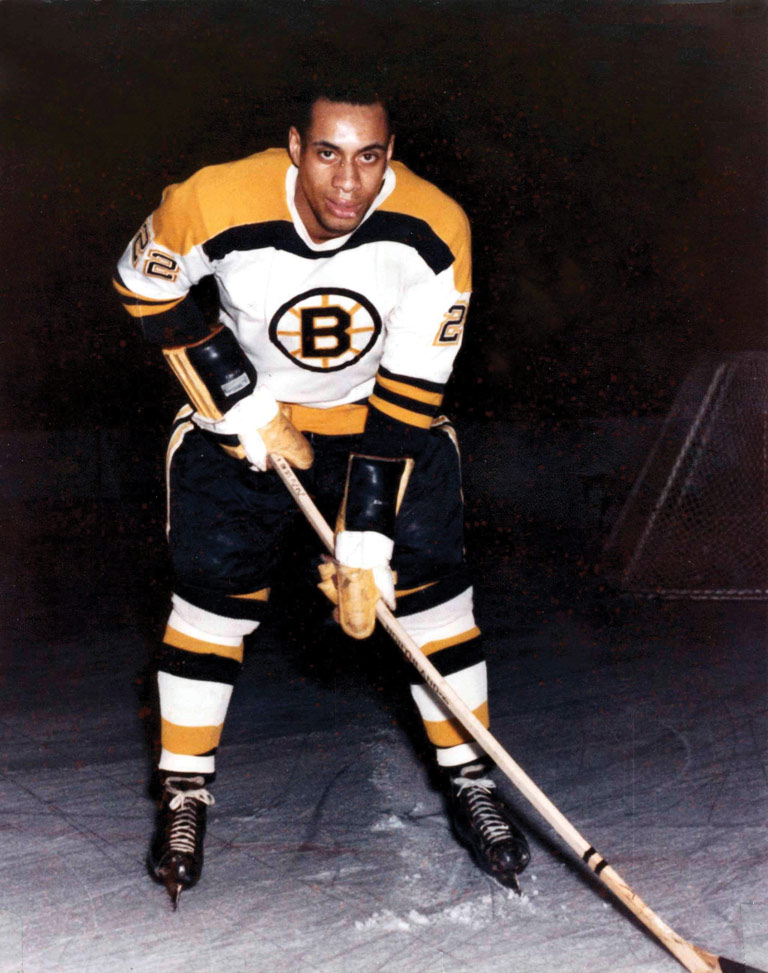

Trailblazer

Sometimes remembered as “hockey’s forgotten pioneer,” Willie O’Ree became the first Black NHLer but received little of the spectacle that followed Jackie Robinson’s integration of major league baseball. Nextday coverage mostly missed the magnitude of O’Ree’s achievement in his Boston Bruins debut in January 1958. In a 22-year pro career tainted by relentless racial abuse from both players and spectators, O’Ree played just 45 NHL games. “I wanted dearly to be just another hockey player,” O’Ree says in Brian Kendall’s 1994 book, 100 Great Moments in Hockey, “but I knew I couldn’t.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Game Changer

It happened so quickly, the play-by-play call of “Heaney! Beautiful move. Shot and a goal. What a play by Geraldine Heaney!” failed to wholly capture her sublime deke and amazing pass to herself through the legs of USA defender Lauren Apollo. Then, with goalie Kelly Dyer scrambling out, diving for the puck, Heaney capitalized, timing her shot perfectly into the top corner beyond Dyer; it scored the goldmedal winner at the inaugural 1990 IIHF Women’s World Championship. Not done, still at breakaway speed, Heaney’s skate caught Dyer’s blocker, launching her airborne, Bobby Orr-style, before she crashed into the end boards.

On paper, like the announcer’s call, the words diminish the virtuoso performance of Heaney’s artistry on ice. With that momentum swing, Canada, attired in their infamous pink-and-white uniforms, scored twice more, defeating the USA 5-2. Centre France St-Louis figured in four goals, but the level of Heaney’s play signalled the arrival of women’s hockey on the world stage. The play became the dream of every girl watching.

Teen Titans

Canada’s teens came into the 1991 IIHF World Junior Championship icing stellar talent in 17-year-olds Eric Lindros and Scott Niedermayer and several future 1,000-game NHLers (among them, Kris Draper and Patrice Brisebois). An unlikely hero, however, emerged among the world’s next superstars to deliver arguably “the biggest play ever” on Saskatchewan ice.

With the Soviets carrying the play late in the taut gold medal 2-2 tie, scoreless rearguard John Slaney intercepted a clearing pass off the boards by Alexei Kudashov. Slaney blasted a hurried shot through traffic and beyond goalie Sergei Zvyagin. Saskatchewan Place went wild, as did TV viewers across Canada. With 5:13 left on the clock, Canada hung on, stymying the Soviets’ onslaught. Today, Slaney’s goal in Canada’s victory is still regarded as “a watershed moment” that elevated the Boxing Day-New Year’s tournament into a holiday ritual.

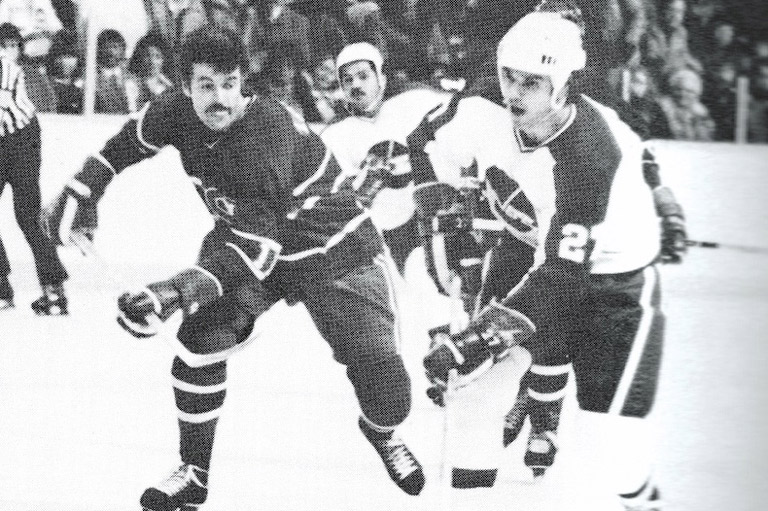

Summit Showdown

No play better characterizes the mood of an overwrought hockey nation — nor the earlier action, drama or cliffhanger suspense of the 1972 Summit Series between Canada and the Soviet Union — than Paul Henderson’s legendary tournament winner.

“When I saw it go in, I just went bonkers,” remembers Henderson in 100 Greatest Moments in Hockey. His face, lit up in jubilation, reflected Canada’s euphoria and the whew-factor back home. With our national self-worth at stake, victory came with 34 seconds left in the eight-game series. Yvan Cournoyer’s celebratory bear hug spoke volumes, his number 12 and “CANADA” loudly, proudly blazoned across the back of his sweater. Fallen goalie Vladislav Tretiak eyed Henderson. The screened audience of Soviet supporters and military men at Moscow’s Luzhniki Ice Palace stared away, stunned in disbelief and dread.

Two disparate hockey rivals — Europe’s most decorated world champions and Canada’s best professionals — collided for the first time ever in a game of brinkmanship that transcended the boundaries of sport. Cocky, commercialized and conned by our stagnant pro game, the Summit Series’ unifying experience defined Canadian hockey and us as Canadians thanks to that moment in time.

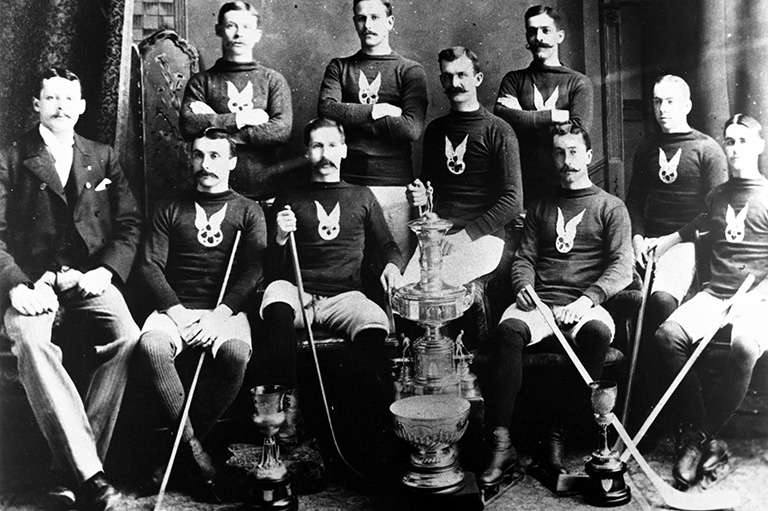

The First Stanley Cup Champions

Magnificent in their famed blue jerseys and white twin-winged wheel crests, the Montreal AAA evoke those nascent years of 60-minute men competing without protective gear, on natural ice and playing short seasons of eight games in the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada — the top senior league in the country. Without a playoff format in place, the inaugural Stanley Cup of 1893 was awarded to Montreal based on season wins, which came in their last match, a 2-1 victory over the Montreal Crystals. While no direct mention was made in local newspapers, the Montreal Star reported that the team claimed top seed and so the championship, as “the puck flew up and down and sticks were whacking on skates and the crowds cheering and shouting on all sides” in that final contest. Months later, Lord Stanley would return to England, never having attended a match in competition for his Cup.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement