Cheering Confederation

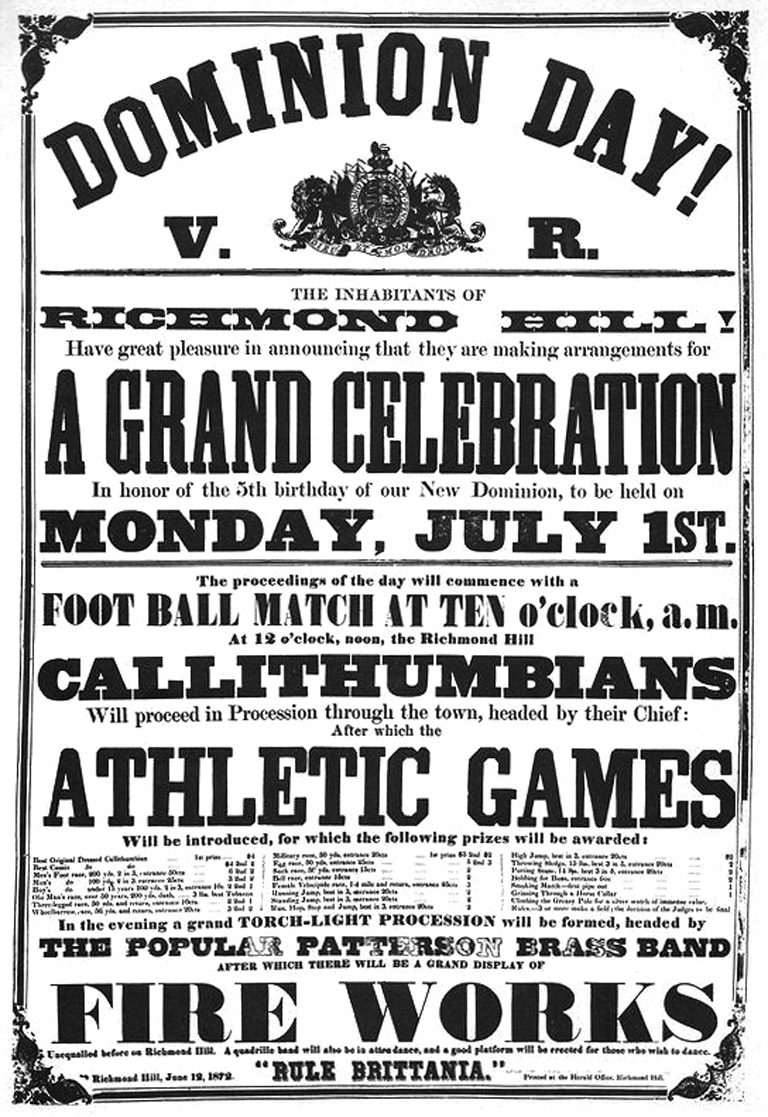

Say the words “Canada Day,” and images come to mind of fireworks, barbecues, outdoor concerts, and trips to the lake or the beach. We owe this public holiday to the Dominion Day Act, which received royal assent on May 15, 1879, and set July 1 as Dominion Day, the day to celebrate Confederation. Since then, Canadians have marked July 1 in many ways. During times of peace and periods of war we have used the holiday to connect with each other and with our country. Here are a few examples of how past generations have observed the holiday.

1867

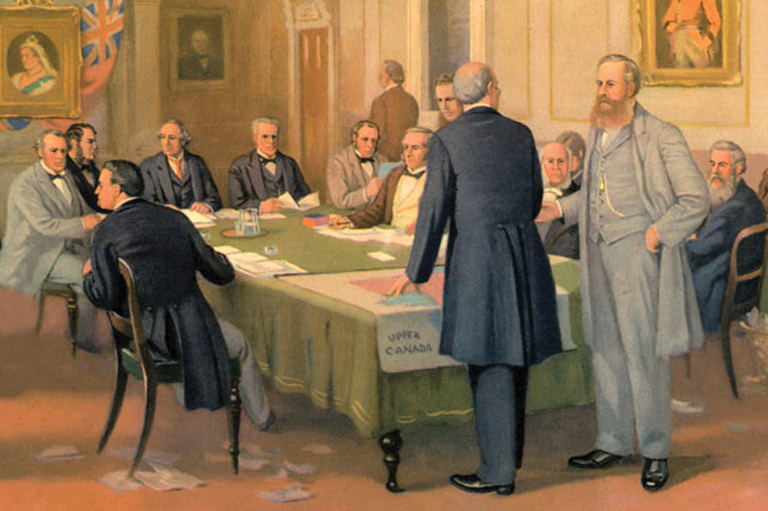

July 1, 1867, marked the enactment of the British North America Act, uniting Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick as a single dominion of the British Empire. In 1868 Governor General Charles Monck proclaimed that Canadians should celebrate the anniversary of Confederation, yet the federal government held no official Dominion Day ceremonies until 1917.

1892

Canada’s twenty-fifth anniversary did not pass unnoticed. The Manitoba Free Press reported “trainload after trainload” of men and women arriving at the Manitoba Turf Club for the day’s races. Explicit references to Dominion Day and Canada’s twenty-fifth anniversary in the newspaper were largely relegated to advertisements for commercial businesses, community picnics, and a grand excursion to Lake of the Woods in Ontario to take in the “fresh breezes of the lake.” Across the country, communities celebrated in similar ways, with picnics, trips to the beach, fairs, and horse, foot, and boat races.

1917

Canada’s fiftieth birthday saw the first official federal government program for Dominion Day. In Ottawa, Governor General Victor Cavendish, Prime Minister Robert Borden, and Opposition leader Wilfrid Laurier each delivered speeches in front of the Parliament Buildings, part of which were being rebuilt. The Centre Block of the previous Parliament Buildings had burned in 1916. With the First World War raging in Europe, the new Centre Block of Parliament was dedicated “as a memorial to Confederation Fathers and to the valour of Canadians fighting in the front line.” Across the Atlantic, Canadian soldiers in France also took part in a special Dominion Day service.

1927

On July 1, 1927, telegraph and telephone companies and twenty-three radio stations united to give a cross-country broadcast of Canada’s diamond jubilee celebrations at Parliament Hill. Canadian National Railways magazine reported that “at least five million people” listened to the broadcast.

1942

Canada’s seventy-fifth anniversary fell during one of the darkest periods of the Second World War. Germany had captured most of Europe, and Japanese forces were advancing throughout the Pacific theatre. In an effort to boost morale, officials declared June 29 to July 5, 1942, to be Army Week. In Ottawa, events included military and cadet parades, a presentation of the flags of the Allied nations, and a mass singalong open to all on Parliament Hill.

1967

Spirits were high as Canada entered its centennial year. A bold new vision of the future was unveiled on April 29 in Montreal: Expo 67, a world’s fair that ran with sellout crowds until the end of October. Expo 67 was considered a shining moment for the country, which was eager to be recognized on the world stage. Popular historian Pierre Berton would later refer to 1967 as “Canada’s last good year.”

1983

In 1982, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government introduced Bill C-201, An Act to Amend the Holidays Act. The act stated that Dominion Day should be renamed Canada Day, with the first Canada Day to take place on July 1, 1983. The name change was praised by some Canadians and lamented by others, who saw it as further erosion of our traditional historic ties to Britain. In honour of the first Canada Day, the Globe and Mail published a Canada Day history quiz.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!