Roots: Combing for Cousins

Is Janice Nickerson stalking you? She’s on the phone, googling, visiting archives, doing everything imaginable to locate the great-great-nieces and nephews of a childless centenarian who left a substantial estate in Ontario.

Not me, you say. Probably not, but can you honestly claim to know the fate of all your great-grandparents’ siblings?

Problem is, even for a professional genealogist like Janice, tracing forward from known ancestors (in this case, the siblings of the deceased) is much more difficult than going back in time. People leave a paper trail of where they were born, went to school and got married. Few — OK, none— are so thoughtful as to document where they will live decades hence, or the names and future spouses of their unborn children and grandchildren.

Then there’s the contemporary penchant for anonymity: Unlisted phone numbers and email addresses are tightly guarded from spammers and Janice alike. It’s a wonder she can find anyone, and when she does, “they sometimes complain about what took me so long!”

Heir searching is a dramatic example of what genealogists variously describe as seeking lost cousins, descendant searching, or researching forward. Here are more reasons why someone may be looking for you:

Reuniting families: Many nuclear families in the past were separated by adoption, war, or other disruption. Genealogist James Thomson helped reconnect two sisters separated for sixty years, one in Canada and one in England. His research transformed the lives of these two elderly women and their families.

Completing the family tree: Reuniting members of a separated family is the most immediate example of “lost cousin” research undertaken by many family historians, such as Linda Reid. Starting with two ancestors married in Ireland in 1872, she has tracked descendants of their twelve children and seventeen siblings to Canada, Ireland, the United States, New Zealand, England, Australia, and South Africa. Be ready for surprises, though. Family historian Diana Thomson learned of an illegitimate daughter of her Orkney great-grandmother and was soon connected with an unguessed-at branch of the family, which she called “a moving and very memorable experience.”

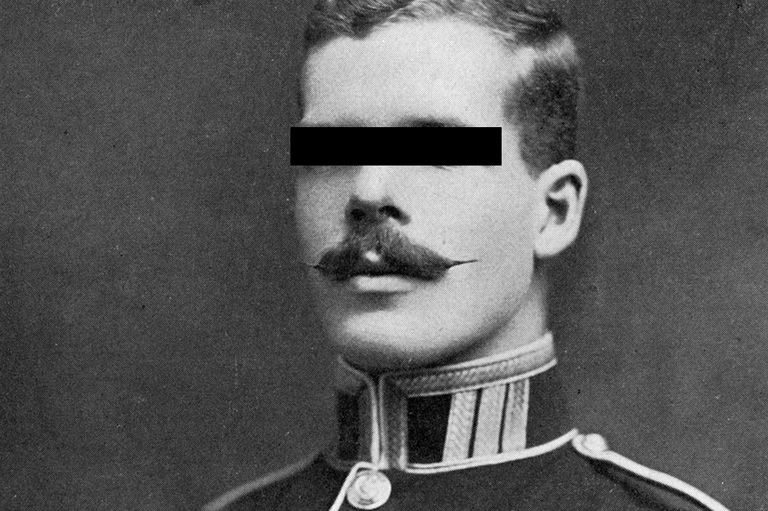

Finding memorabilia: Distant cousins often possess amazing family memorabilia. Thomson’s Orkney relatives sent her a glorious studio photograph of her great-grandmother’s family. My wife’s Victoria cousins brought out a family Bible with unique family listings and annotations.

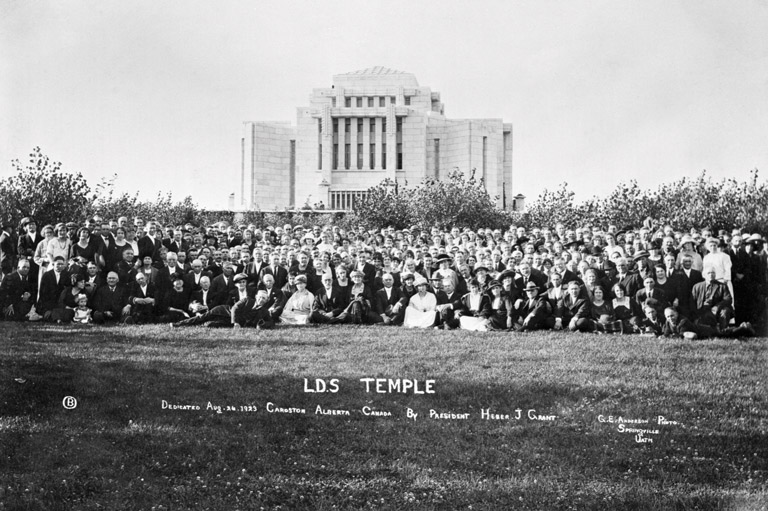

Organizing a family reunion: Knowing everyone in the family is key to a successful reunion. For decades my wife’s Jewish relatives held a biennial gathering to celebrate the 1907 arrival in North America of the patriarch and matriarch. Each successive reunion attracted new attendees as research plugged the gaps in the family tree.

Seeking organ donors: On a more serious note, relatives are much more likely to make compatible organ donors than members of the public at large. If you needed a kidney, how widely could you cast your familial net? Building a medical pedigree: Is there a genetic disease in your family? A trick question, as yes is the only correct answer. This may not be apparent if you know only your birth family and one or two aunts or uncles.

Learning from DNA: With the expected growth in sophistication of autosomal DNA testing, the more genetic reference points in one’s immediate family tree, that is, the more “cousins,” the better the predictions will be about the unknowns in the tree.

Identifying remains: In one of the most celebrated examples of descendant searching, American genealogist Megan Smolenyak Smolenyak worked for a decade with the U.S. Army tracking down next of kin of soldiers who served in the First and Second World Wars, in Korea, and in Southeast Asia. Genetic testing then confirmed whether newly discovered remains had been correctly identified.

Finally, there’s one time when you don’t want to research forward in time. Despite your family’s long-standing belief that you are descended from one of the fourteen illegitimate children of Charles II, researching forward never makes sense to establish a pedigree. Each generation conservatively produced a quintupling of the number of lines of descent. Compounded over a dozen generations, that amounts to millions of people today. Frankly, it can’t be done.

Except in my case. According to my grandmother, we’re descended from the composer Handel. Researching backward seemed like an immense challenge, but researching forward was a snap.

Handel died childless, so the story is bogus — or a real scoop!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!