Rulers of the Court

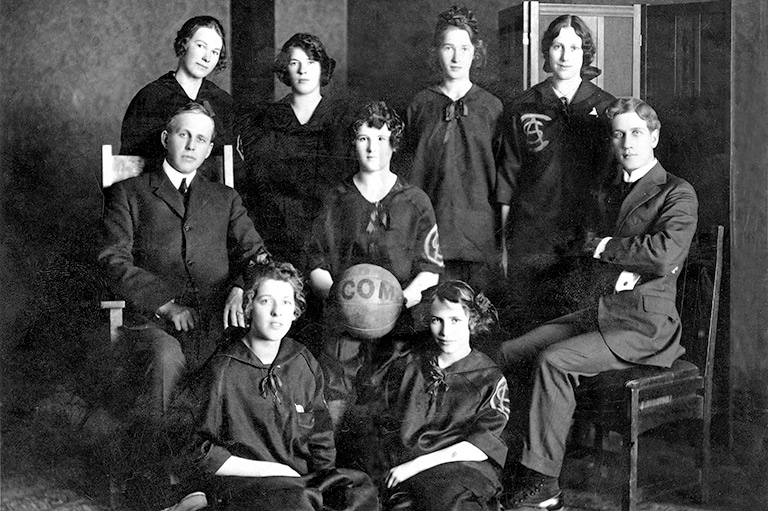

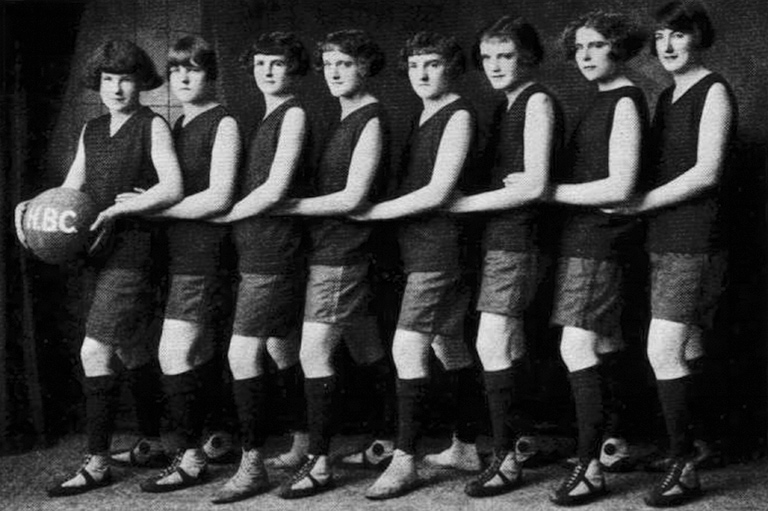

The gym at Edmonton’s Victoria High School was packed for the Alberta women’s provincial basketball championships. Scores of the home team’s enthusiastic rooters filled any available spectator space to watch its players face an all-star group from Wetaskiwin, Alta. It was March 24, 1917, and this was the first game the Edmonton team had played under its new name: the Commercial Graduates, better known as the Edmonton Grads.

At that time, the teams played under “women’s rules” — two forwards, two at centre and two on defence. The local team gained an early advantage due mostly to the sharpshooting of forwards Nellie Batson and Ella Osborne, although the visitors fought back with smart plays and accurate passing. The score at halftime stood at 12-7. Wetaskiwin played well in the early stages of the second half; so well that, at one point, the Grads led by only three points. Things got a little rough; Edmonton player Ethel Anderson committed four fouls and was kicked out of the game. Not to be outdone, the Grads pulled away from their opponents in the closing minutes with a beautiful exhibition of passing and shooting. The final score was 30-14. The press called it the best game of “ladies” basketball ever seen in Edmonton and noted that the players went at it as fearlessly as any man ever did.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

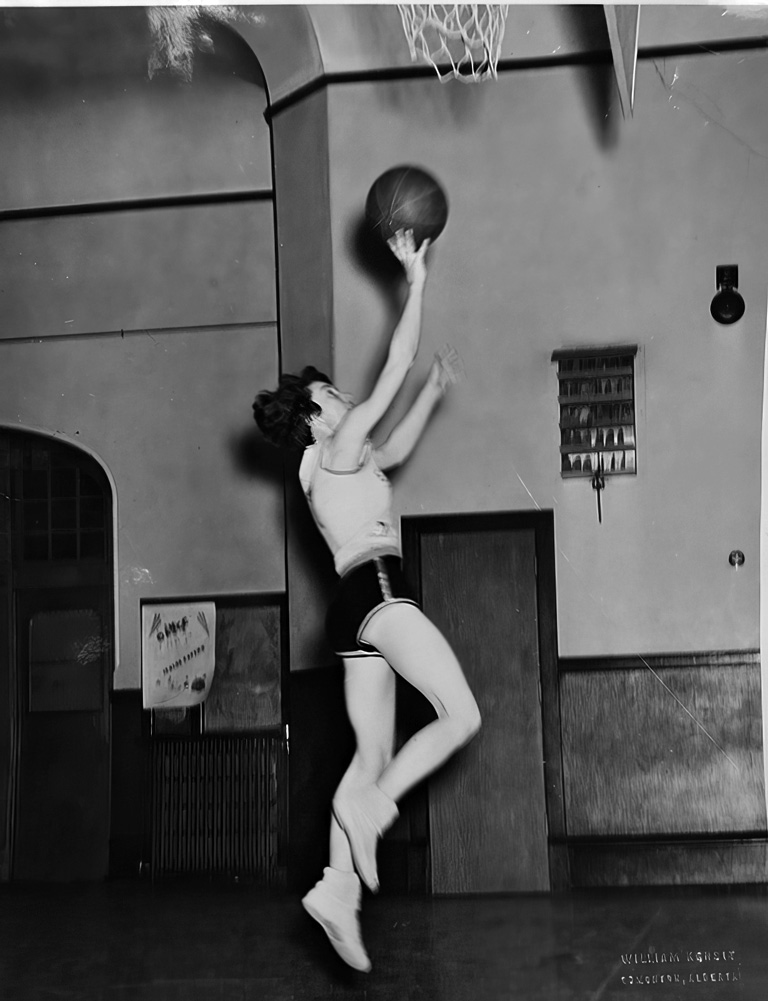

Some 10 decades later, history is about to be made again. This May, 30 years after the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) was founded, the Toronto Tempo — the league’s first Canadian team — are set to make their debut. But the WNBA isn’t the only professional basketball game in town. Since 2020, the HoopQueens league, which consists of four teams, has brought together top-tier talent, offering competitive play and financial support for female athletes over a five-week season at Humber College in northwest Toronto.

It’s exciting news for Canadian fans and players, who may not know that even before these developments, Toronto had a history of producing winning — though not professional — women’s basketball teams. In the 1920s and ’30s, the Toronto Lakesides, the Young Women’s Hebrew Association, the Toronto Ladies Athletic Club and the Toronto Maple Leafs all competed for the Canadian women’s title. None, however, was able to defeat the Edmonton Grads, the most successful women’s basketball team in Canadian history. Between 1915 and 1940, the Grads dominated competition in Canada, the United States and Europe. This is their story.

A major assist

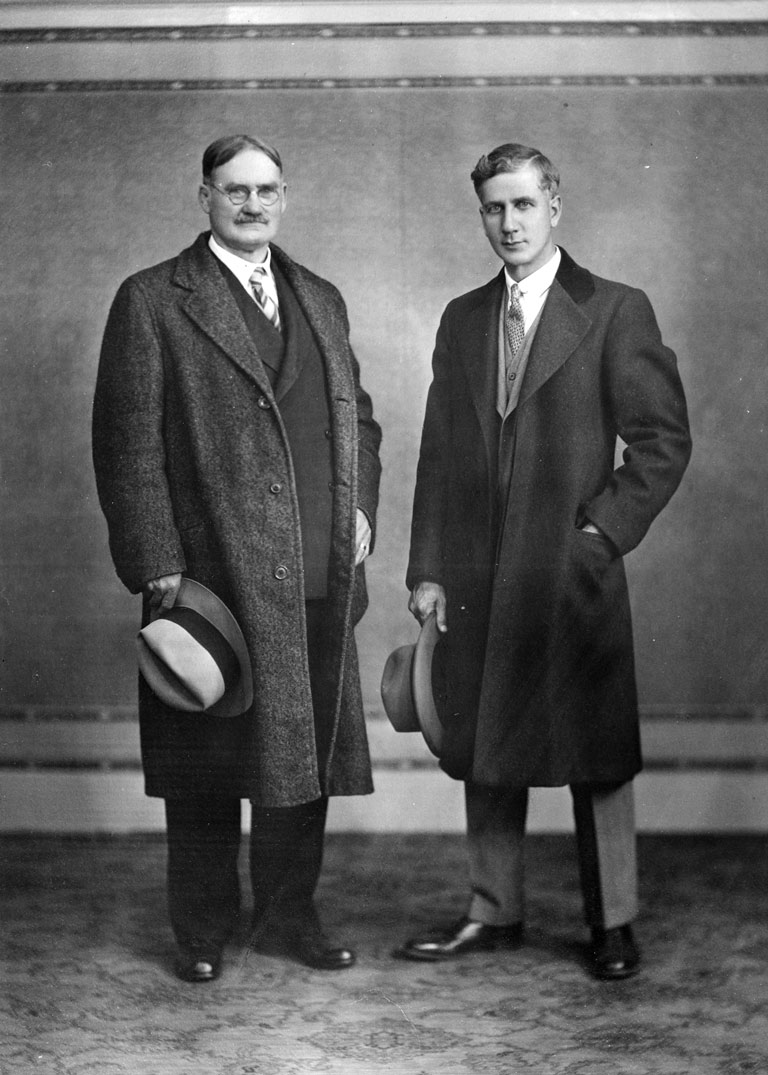

Principal Percy Page introduced girls’ basketball to Edmonton’s McDougall Commercial High School in 1914 through his physical education classes.

At the time, the sport was only 23 years old. In the newly established city high school league for girls, the Commercial team beat the three other schools and won the league. They also dominated the freshly created Alberta provincial championship. Several female students who were graduating from Commercial wanted to continue to play basketball and persuaded Page to coach a city team, which they named the Edmonton Commercial Graduates.

According to team records (which are supported by newspaper accounts), the Grads played 428 official games between 1915 and 1940, when they disbanded. The team lost very few games — 20 is often cited. This gave them an overall win-loss record of an amazing 95 per cent. By comparison, the winning percentages of today’s top WNBA teams are in the 60 to 77 per cent range. As perpetual winners of the Alberta provincial championship, the Western Canadian finals, the Canadian championship, the Underwood International Trophy (USA-Canada) and the North American championship, the Grads were almost impossible to beat. They also crossed the Atlantic Ocean three times and won every game against teams in Europe.

Why were the Grads so successful? Over the years, Page and his assistants created a remarkable organization that included several feeder teams (the junior Gradettes, for example) and the Boy Grads (with whom they practised), as well as several coaches, local businessmen and prominent Edmonton citizens. The Grads brought unprecedented publicity to the city, especially as they became more widely known throughout the U.S. and Europe. In Edmonton, the Rotary Club and its members were highly enthusiastic team boosters, providing Page with advice concerning the financial and business aspects of the team. When players were looking for work, they were often employed by Rotarians.

The team was like a multi-generational family with Papa Page as its head. He treated his players with care and, in return, demanded respect and loyalty. Above all, he and his wife, Maude, expected them to be gracious young ladies in every aspect of their behaviour and deportment. Page didn’t lay down specific rules of conduct; rather, he set those standards through example. Basketball talent was not in itself a passport to membership on any team in the Grads’ organization.

In total, the Edmonton Commercial Graduates had 38 official members (counted onward from the 1922 team, which won the first Canadian women’s basketball championship). Together, they spanned almost three generations, with the oldest born in 1899 and the youngest in 1922. Many of the original Grads were from working-class families who had immigrated to Edmonton from the British Isles or the U.S. for a better life. Most, however, had either been born in Canada or indeed in Edmonton. All but two were graduates of McDougall Commercial High School, and in addition to playing for the Grads, the majority took jobs at local Edmonton businesses as secretaries, stenographers, clerks and sales personnel, although two became teachers. After leaving the team, they led lives as varied as any group of women of this era. Almost all married, some more than once. Most had children, but a few did not. Many lived a long time and saw their grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren, but several died far too young.

Advertisement

Travelling

Page believed wholeheartedly in basketball for girls and women. He also realized, as the Grads’ reputation grew, that they could play an important role in promoting the game across Canada and the U.S. and in Europe. Luckily, Edmonton had a facility that would allow Page to invite teams, especially from the States, to come north. Built in 1913, the Edmonton Arena was a barn-like structure with a floor larger than New York’s Madison Square Garden and a capacity for 6,000 spectators. Over the years, it held livestock exhibitions, motor shows, circuses, pageants, athletic contests and, of course, hockey games, with the ice made from scratch every winter. When the Grads needed it, a specially built wooden floor that accommodated a basketball court was placed in the middle of the arena. The team first played in the facility in 1923, when they brought the London Shamrocks from Ontario for the Dominion championships. From then on, it was the site of the Grads’ many victories — and a few losses, primarily against teams from the U.S.

During the summer holidays, the Grads almost always went on a barnstorming tour south of the border. Generally, they played against industrial teams, such as the Favorite Knits in Cleveland or the Taylor Trunks and the Uptown Brownies in Chicago. When similar teams came to Edmonton, they sometimes picked up one or more top players from other squads in the hope of beating the Grads. It rarely worked.

Olympic champions?

Among the various accounts of the Grads’ accomplishments, some say they were Olympic champions in 1924, 1928, 1932 and 1936. But women’s basketball didn’t become an Olympic sport until the Montreal Games in 1976, nor was it ever a demonstration sport at any prior Olympics. The confusion can be partially explained by the Grads’ trips to Europe at the same time as the Summer Games in Paris (1924), Amsterdam (1928) and Berlin (1936), as well as to Los Angeles in 1932. Why?

By 1923, the Edmonton Grads had defeated three teams from the U.S., including one that claimed to be “world champions.” But the Grads couldn’t properly claim that title themselves unless they could also beat a championship team from Europe. Page was aware of the efforts, especially by women’s sport leaders in France, to petition the all-male International Olympic Committee (IOC) to include more women’s events in the Summer Games. He contacted Alice Milliat, whose Federation sportive feminine internationale (FSFI — the International Women’s Sports Federation) organized sporting events for women. Milliat invited the Grads to take part in a special tournament in Paris that she planned to run at the same time the men’s Olympic contests were taking place. The only stipulation was that the Grads be officially recognized as Canadian champions by the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada, which it did willingly.

The team raised some money and sailed for Europe in July 1924. They played local teams in Paris, Strasbourg, Roubaix and Lille, defeating them all by lopsided scores. As a result, the Grads were given the undisputed right to the World’s Basketball title by the FSFI.

Again in 1928, Milliat invited the Grads to take part in a European tour in conjunction with the Summer Games in Amsterdam and to defend their world title. During July and August, the team visited seven countries and played nine games, mainly against competitors in France. They won all of those matches — often besting their opponents by 60 to 70 points — and retained their world championship by defeating an all-star team with players from Paris, Reims and Lyons.

Although the Grads travelled to Los Angeles in 1932, they never hit the court there; this was because the IOC urged unnecessary sporting events to cease during the Games. It seems likely that Page decided to make the trip to lobby the IOC for the inclusion of women’s basketball in the Olympics. In 1936, as she’d done for previous Olympics in Europe, Milliat invited the Grads and arranged exhibition games for them in London, Paris, Marseille, Nice, Monte Carlo, Rome, Florence, Milan and Strasbourg; again, they defeated every team by the usual uneven scores. At the Olympics in Berlin, the Grads were allowed to sit in the stadium’s competitors’ section and wear the official Olympic blazer because the Canadian Olympic Committee recognized the team as part of the Canadian contingent. Sadly, Page died in 1973, so he never did see women’s basketball become an Olympic sport.

The end of an era

On the night of June 5, 1940, more than 6,000 devoted fans filed into the Edmonton Arena to watch the Grads play their last game, which was against the Chicago Queen Anne Aces. It was the third of an exhibition series, and having already won the first two games, the Grads finished it off with yet another solid win. The next evening, the banquet room of the Corona Hotel was packed with some 250 guests who were there to honour the team’s accomplishments and mark its end.

There were a few clear reasons why the Grads disbanded. The federal government had taken over the Edmonton Arena for military training, so it was impossible to schedule games, which were no longer regularly well attended. Besides, games were now available to listen to on radio. The Second World War made travel difficult, even in North America, and all international competition had been cancelled. Finally, Page was a busy man — teacher, principal and, most recently, a provincial politician — so he couldn’t devote as much time to the team as he once did.

In 1950, the Edmonton Grads were voted Canada’s greatest basketball team of the first half century by sports editors and sportscasters in a Canadian Press poll. Inducted into several sports Halls of Fame, the team has received many additional honours; for instance, there’s a plaque by Parks Canada “commemorating the national historical significance” of the Grads at the entrance to Commonwealth Stadium in Edmonton. There’s also Edmonton Grads Park, located in the city’s Westmount area. In 2025, the Edmonton Transit Service ran a historical bus tour so patrons could learn about the players and the businesses who supported them and see where they lived and played in the city.

But their legacy is best summed up by James Naismith, the Canadian inventor of basketball, who, on the 25th anniversary of the Grads in 1936, said: Your record is without parallel in the history of basketball. There is no team that I mention more frequently in talking about the game. My admiration is not only for your remarkable record of games won (which in itself would make you stand out in the history of basketball) but also for your record of clean play, versatility in meeting teams at their own style, and more especially for your unbroken record of good sportsmanship. It is the combination of these things that make your record so wonderful.

Women’s basketball, especially in North America, has changed a great deal since the Grads dominated the sport. The WNBA has a number of women in head-coaching roles (close to a 50-50 split versus the NBA’s zero) and the teams are much more diverse. Plus, with the Toronto Tempo, Canada is back in the game. Big shifts, yet the spirit remains the same.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Them’s the rules

During the Grads’ time, there were two versions of basketball rules: women’s and men’s. Women were restricted to two-thirds of the court, only two bounces before a pass and other restrictions. Eastern Canada (mostly just Ontario and Quebec) used women’s rules; Western Canada used men’s rules. The Grads’ coach much preferred the men’s rules because the American teams who came to Edmonton used them. When the Grads travelled east, they mostly had to play women’s rules, and sometimes, games were played with one-half women’s and one-half men’s.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement