Mosaic in the Making

“Welcome to Hindi Heights. Population: 2 Many.”

In early 1975, someone affixed the handbill to a pole in a Vancouver neighbourhood whose South Asian residents were becoming targets of racial aggression: graffiti, vandalism, stones thrown at the windows of homes. White residents complained about “poor driving skills” and losing jobs to these newcomers. Vancouver’s newspapers played up the tensions. In one case, several Indian men set up a watch group, the East Indian Defence Committee. The Province labelled them “vigilantes.”

Former British Columbia premier Ujjal Dosanjh, who arrived from India in 1968 and was in law school, recalls that South Asian immigrants initially were well accepted, but something shifted as large numbers of tourists began arriving in the province and applying to immigrate. “It was around that time you had people being spat at on buses, windows being smashed at night with rocks,” says Dosanjh.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

This sentiment wasn’t confined to Vancouver; it swept into Toronto as well, with attacks in public spaces and an area known as Little India on Gerrard Street East, a cluster of restaurants, groceries and boutiques anchored by a Bollywood theatre, says historian Aqeel Ihsan. On the subway, “someone might call you a derogatory slur, someone might spit on you, comment on your skin colour, comment on how you smell. There were a lot of smell-related incidents,” he says.

Experts sought to account for what seemed like a split screen in public opinion. After all, at the very height of 1960s progressivism, Canada had replaced the use of racial categories and quotas with a colour-blind points system, formalized its refugee policy and loosened admission rules to allow more extended families.

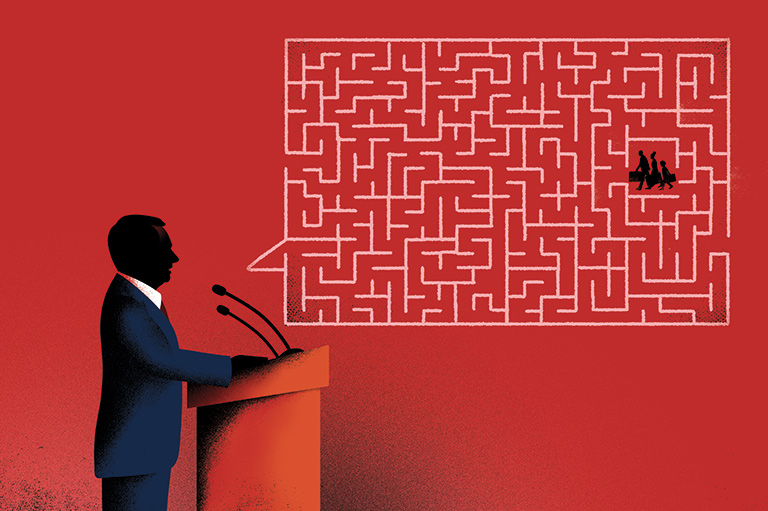

Yet, even before stories about anti-South Asian blowback began to dominate headlines, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals had an inkling its reforms weren’t landing, despite all the sunny rhetoric about Canada as a cultural “mosaic.” In 1974, the federal government released a green paper on immigration to tee up the work of a special parliamentary committee and public hearings, all in the service of passing a new immigration act.

The timing wasn’t great. The 1973 OPEC oil embargo had triggered stagflation and unemployment. The political Tetris facing Trudeau was to overhaul an antiquated immigration system, re-establish administrative order, deliver labourforce goals and win re-election.

As for the attacks on South Asians, the special committee’s December 1975 report devoted just three pages to the topic. While acknowledging how, during hearings, MPs and senators were told that immigrants brought infectious diseases, crime, overcrowding and slums, and also took advantage of Canadian social programs, the authors stressed there was no evidence to support those claims. “[M]isconceptions,” they concluded, “abound.”

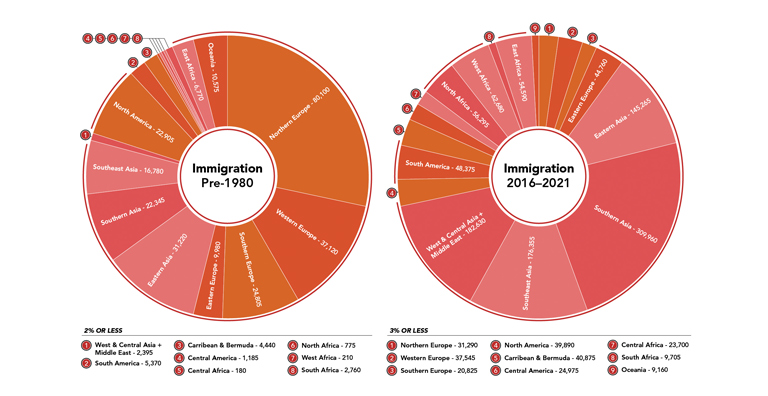

Except for the past two years, it’s possible to see postwar immigration in Canada as a mostly linear narrative — the mythic tale of an overwhelmingly white country that decamped from the killing fields of Europe, eventually emerging as a post-racial urban society that embraces ethnocultural diversity more completely than any other place on earth. Canada’s big cities, though hardly perfect, buzz with the entrepreneurial energy of newcomers. Campuses and professions like medicine and engineering mirror our shifting demographics, as do traditionally impermeable vocations, such as journalism and law. Systemic bias and anti-immigrant bigotry still exist, and there have been terrible acts of racial violence in London, Ont., and Quebec City. However, Canada’s nativists lack a mainstream political home.

Whatever we did worked until 2023, when public-opinion surveys showed a sharp backlash against elevated post-COVID immigration levels, temporary foreign-worker programs, international-visa students and refugee claimants. For the first time since the late 1990s, more Canadians feel there’s too much immigration than those who support it.

Current fears about a system adrift offer a historical echo of how Canadians and their governments navigated postwar societal change — a period that began with tentative moves away from an explicitly exclusionary outlook and ended in the late 1980s, when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney tripled Canada’s annual immigration targets, to 250,000 newcomers.

Successive governments have justified immigration reforms in terms of their economic and demographic payoffs, and occasionally in moral terms. Their annual targets ebbed and flowed. But they also routinely engaged in bureaucratic equivocation in the face of perceived, and real, opposition from Canadians. Those policies, in turn, were shaped by tectonic global forces, such as the Cold War, the dissolution of the British Empire, the rise of air travel and the pace of European reconstruction.

The messiness and the mythology are indivisible, observes Dosanjh. “Both of those things were true, in that you had this sense that we were integrated and generally well accepted, but then you have the rise of right-wing racist groups,” he says. “These two realities continue to co-exist. It’s not really mythology, and it’s not really the truth, either.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Canada is a country built by European colonists and Asian labourers on the ancestral lands of hundreds of Indigenous nations. The young dominion allowed early non-British and non-French immigration for functional reasons, such as bringing in eastern and southern Europeans to mine and farm. Jews fleeing Russian pogroms arrived en masse in the early 20th century, settling in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg.

According to a 1930 order-in-council, Canadian officials wanted only white, Christian and preferably English-speaking newcomers from the British Isles, northern Europe or the United States. They throttled the flow of people from elsewhere using head taxes and strict rules preventing family reunification, in the case of Chinese labourers, or more subtle measures, such as the notorious “continuous passage” regulation that permitted South Asian immigrants to land here only if they’d sailed directly from colonial India (most couldn’t).

Immigration flatlined during the Depression. Our policy soon took a darker turn with the internment of Japanese and German Canadians, and the infamous 1939 decision by one of Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s officials, Frederick C. Blair, to send the MS St. Louis, a Halifax-bound ship carrying 930 Jewish refugees, back to Europe, where hundreds eventually were murdered under Nazi Germany. “It is manifestly impossible for any country to open its doors wide enough to take in the hundreds of thousands of Jewish people who want to leave Europe,” he told King. “The line must be drawn somewhere.”

In the war’s immediate aftermath, Canada agreed to admit 4,500 Polish veterans stranded in the U.K., as well as 40,000 war brides and their children from England and the Netherlands. “This starts to get federal immigration officials thinking about what type of early postwar immigrant and refugee desirability looks like,” says Jan Raska, a historian with the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, the primary entry point for nearly one million immigrants and refugees during the Second World War.

King, a political shape-shifter, set in motion changes that opened the door to a four-decade-long conversation about who gets to come here and why. King surely didn’t see it that way. In an oft-quoted 1947 speech, he affirmed “the view that the people of Canada do not wish, as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population.” That character, he said, didn’t include “large-scale immigration from the Orient.”

Advertisement

Besides the head tax and the restrictions on family reunification, the government used hard caps to limit immigration from South Asia. In the 1940s and ’50s, says Ihsan, “there was a quota in place whereby 150 Indians could come over, 100 Pakistanis could come over, and 50 people from Ceylon [modern-day Sri Lanka].”

King was keenly aware that the U.S. and the United Nations wanted Canada to do more to alleviate Europe’s insoluble refugee crisis, which stranded millions of displaced persons (DPs) and Jewish Holocaust survivors. Canada, moreover, had committed heavily to the creation of the UN and had little choice but to pay attention or face accusations of hypocrisy. Pressure was coming from inside the country, too. “The doors of Canada must be opened to the homeless and the helpless,” David Croll, a Toronto MP with a large Jewish constituency, was quoted as saying in the Globe and Mail in 1946.

While Allied powers initially wanted to send DPs back to their homes, British officials began considering importing refugees to relieve labour shortages, an idea that soon alighted in Ottawa. King appointed a Manitoba MP, James Glen, as minister of immigration and established a parliamentary committee. The Liberal caucus was sharply divided, but King argued that Canada’s population needed to grow to a level he described as its “absorptive capacity.”

The prime minister also did something unexpected. After lobbying by a pan-Canadian network of Chinese organizations and churches (the Committee for the Repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act), King in May 1947 signalled his intention to repeal the discriminatory 1923 Chinese Immigration Act, which he once described as a “mistake.” He also promised to loosen restrictions on family members who Chinese residents could sponsor to come to Canada. China, after all, had been a wartime ally and our army included about 500 Chinese-Canadian soldiers.

Those new measures found their way into law. However, limits on Chinese immigration, and from other regions in the Global South, lived on in bureaucratic processes embedded in federal regulations, allowing officials to exclude applicants based on “peculiar customs, habits, modes of life or methods of holding property [and] unsuitability having regard to the climatic, economic, social, industrial, educational, labour, health, or other conditions, or requirements existing, temporarily or otherwise.”

Between 1947 and 1952, Canada took in more than 186,000 DPs from war-ravaged Central and Eastern Europe, with many selected specifically for sought-after technical skills. Yet, Jewish DPs, as the late historian Irving Abella writes in None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933- 1948, were “a case apart.” The government, under pressure from Jewish aid groups, concocted largely symbolic programs geared at orphan DPs or those in the needle trades. But the ghosts of Canada’s prewar antisemitism lingered, with Jews, who made up 30 per cent of all of Europe’s refugees, accounting for just 15 per cent of DPs admitted to Canada in 1948.

“My parents … spent four years in a concentration camp,” recalled former Supreme Court justice Rosalie Silberman Abella — wife of Irving Abella and the first Jewish woman and the first refugee to be appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada — in a 1998 speech marking the 70th anniversary of Pier 21. “After years of trying to get into Canada, we finally got permission. In May of 1950, my parents, my grandmother, my younger sister and I found ourselves on an American troop ship, the [USS General Stuart Heintzelman], headed for Halifax. We landed at Pier 21, immediately got on what my mother remembers as a soot-filled train headed for Toronto, and started our lives all over again.”

In recent years, University of Toronto historian and doctoral candidate Catherine Grant-Wata has interviewed 30 older women from Jamaica who moved to Canada and the U.K. in between the 1950s and ’70s, many initially as “domestics,” part of a 1955 federal program geared at bringing in nannies and housekeepers — and later, nurses and teachers — from the “West Indies.”

Ottawa’s motives were hardly open-minded. There was a demand for Black domestics, fuelled in part by the fact that affluent families were having more difficulty in the postwar years hiring European housekeepers, says Natasha Henry-Dixon, an assistant professor of history at Toronto’s York University and president of the Ontario Black History Society. “To fill that gap, the government was looking to other places in the British Commonwealth and so drew on women from the Caribbean,” she says.

Immigration officials spoke openly about these “coloured” newcomers in racist terms, citing tropes about work ethic and their inability to adapt to a cold climate. Some also feared an influx of Black immigrants would bring the race tensions then flaring in the U.S. to Canadian cities. As with South Asians, the department imposed annual quotas.

As the Caribbean islands attained independence from Britain in the early 1960s, diplomats from those emerging post-colonial nations sought not only to build links with Canada to promote investment, tourism and foreign aid but also to manage the growing desire among many of their residents to leave. “They were fleeing the conditions of home, the legacy of slavery,” says Henry-Dixon.

As the West Indies domestics program expanded, the federal Liberals, now led by Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, found themselves buffeted by another seismic international event: the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, which began in October, and the subsequent exodus of tens of thousands of people fleeing Communism. The uprising made headlines globally as the revolutionaries became a cause celebre. As with the postwar DPs, the federal government’s initial response was to throttle any pressure to admit large numbers of refugees stranded in Vienna. However, something about this revolution caught the imagination of many Canadians, who began organizing to provide relief as well as offers of sponsorship and jobs.

Within weeks, Canada’s policy response pivoted. It included dispatching Canadian ships and planes to bring over refugees, who were greeted by cheering crowds in Halifax and Montreal. More Hungarians ended up in Canada than in any other country. And while there were pockets of dissent — some Second World War veterans objected because Hungary had been allied with Hitler — the sky did not fall. The fact that these newcomers were white and European made them much more palatable in a still sparsely populated country that continued to nurse hang-ups about race.

Ellen Fairclough was an unlikely pioneer. A bookkeeper from Hamilton, she got involved in Conservative Party politics after the war and won a 1950 federal by-election. When John Diefenbaker defeated St. Laurent’s Liberals in 1957, he named her secretary of state, the first woman to serve in cabinet. The following year, the prime minister offered up a promotion: minister of immigration and citizenship.

Fairclough quickly began hearing from ethnocultural groups about the problems they were encountering with Canada’s restrictive immigration rules. One organization was particularly outspoken: “We are still not on equal footing with European immigrants,” W.C. Wong, the new president of the Chinese Canadian Community Centre of Ontario, told Diefenbaker and Fairclough at a banquet. The group dispatched a delegation to meet Diefenbaker to press for changes to the law that weren’t made in 1947 when King repealed the Chinese Immigration Act.

Fairclough pitched the prime minister on convening a royal commission on citizenship and immigration, which he rejected. Undaunted, she proposed removing, once and for all, the racial categories embedded in the Immigration Act — a reform adopted in February 1962. That move, as well as another Diefenbaker directive — to peg annual immigration levels to one per cent of the population — represented a clear policy break from the past and opened the door to far more immigration from Asia, Latin America and Africa than ever before. Fairclough, says Raska, should be given “her proper due for beginning to take geographic and racial restrictions out of federal immigration policy.”

Diefenbaker’s government, however, was short-lived, losing a general election in 1963 to Lester B. Pearson’s Liberals. In October 1966, the Quebec trade union leader, Jean Marchand, the Liberals’ minister for manpower and immigration, released a white paper on immigration. “There is a general consensus among Canadians,” begins the 35-page document, “that the present Immigration Act no longer serves national needs adequately, but there is no consensus on the remedy.” No one disagrees that Canada needs immigrants, it continued. “The question is what number and what kind of immigrants should be sought in the years ahead, and from what sources.”

The white paper surveyed the arguments orbiting immigration — the justifications (economic prosperity, population growth, a skilled labour force, humanitarian obligations) and also an acknowledgment that Ottawa’s vetting system still favoured applicants from Europe and the U.S. It cited touchier questions, such as the practice of landed immigrants sponsoring non-dependent family members who may not have desirable skills, as well as “cultural and social issues”: Could newcomers from what was then known as the Third World adapt, or would they lapse into criminality or remain stuck in ethnic enclaves, increasing welfare costs?

Finally, the white paper proposed crisp immigrant categories, including definitions for which family members were eligible to be sponsored, the types of people who would be kept out (such as pimps and those deemed “mentally or physically defective”) and the importance of ensuring that formal applications are submitted outside our borders.

By the late 1960s, the new prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, sought to put a more, well, liberal stamp on Canada’s immigration rules, establishing the points system whereby applicants are scored against a set of objective criteria, loosening the rules around applications made by people who’d come as tourists and leaning heavily into refugee admissions.

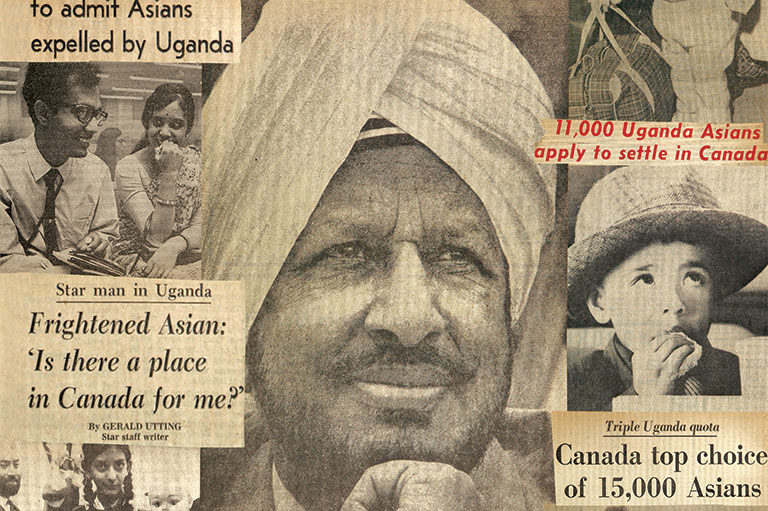

Which were rising quickly. The 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia brought thousands of refugee claimants to Canada, as did Pakistan’s violent 1971 attack on the newly independent Bangladesh. In 1972, when Ugandan dictator Idi Amin threatened to slaughter his country’s Ismaili community, Ottawa expedited the admission of almost 7,000 refugees — an influx that helped ignite the anti-South Asian backlash in the mid- 1970s and put the Liberals on notice that not everyone was on board with their progressive approach. What’s more, the government’s humanitarian efforts were tempered by geopolitics, observes Raska, who says Canada hesitated before admitting thousands of left-leaning Chilean refugees for fear of antagonizing the U.S., which had backed a right-wing coup in 1973.

Despite Trudeau’s reforms, federal officials continued to put their thumbs on the scale, using such bureaucratic workarounds as bolstering the number of immigration officers in desirable places — think London — while limiting them in less-desirable locales, like India. Even the nine-point assessment system allowed immigration officers to impose their biases because the scoring rubric relied on human judgment. “They left in a tiny mechanism [couched under the term ‘personal suitability’] where, if an officer didn’t buy your story, didn’t like you for some reason, didn’t think you’d be a good fit, they wouldn’t give you those points,” says Raska.

In 1974, the Liberals took a second run at overhauling federal policy, but this time with a far more comprehensive assessment and a deadline: an updated Immigration Act, to be presented in 1976. The minister, Montreal businessman Robert Andras, released a four-volume green paper that added new policy goals to the mix, including the need to find French-speaking immigrants to confront Quebec’s stagnating birth rate. Yet, the green paper faced sharp criticism from groups that accused the government of an anti-immigrant bias.

When Andras presented his new legislation (which came into effect in 1978), it marked “a significant shift,” according to the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 — a departure from the ad hoc policy-making that had prevailed since the late 1940s. The law defined refugees as a distinct category of immigrant and formally gave the minister responsibility for planning, which included setting an annual target — a management tool that remains in place to this day.

Stung by reports of anti-immigrant violence, the Liberals set the number low. For the balance of the 1970s and early ’80s, Canadian immigration dropped steadily, except during the Vietnamese boat people crisis in 1979 and 1980, when Joe Clark’s minority Tory government greenlighted emergency admissions of almost 100,000 refugees. When Brian Mulroney came to power in 1984, his Progressive Conservative government largely left Andras’s law in place, adding only a new class — immigrant entrepreneurs with large sums of capital to invest — to take advantage of the growing ranks of emigres from Hong Kong. Yet, in response to public outcry about boatloads of Tamil and Sikh asylum seekers landing on the East Coast, the Tories tightened up the refugee admission processes, accepting only claims made from abroad.

The growing ranks of newcomers — increasingly non-white, from the Global South — found themselves settling in a cold country that hadn’t shed its old prejudices. Professionals like engineers and doctors, admitted on the strength of their training, encountered barred doors. Housing was another headache. “Arrivals from the Caribbean [were] being turned away from renting apartments,” says Henry-Dixon.

Some experienced enduring disappointment, among them a cohort of South Asian-trained physicians who found residencies and medical practices in small towns in Atlantic Canada in the 1960s and ’70s. Though they were able to pursue their careers, many never managed to integrate into their communities.

The merchants on Gerrard Street’s Little India took a more proactive approach to narrowing the cultural divide. Local business leaders created a task force to report incidents, then pushed the Toronto police to hire more non-white cops to patrol their area. They also reached out to media organizations and invited journalists to spend time in their restaurants and homes to demonstrate that they weren’t dirty places, contrary to the innuendo.

Plus, white Canadians got familiar with them, says Ihsan. “Food that used to smell didn’t smell so bad anymore. Butter chicken, chicken tikka masala, all these sorts of things that were first seen as foreign, a decade later, they’re not that foreign anymore. Heck, they even taste good.”

Ujjal Dosanjh has a telling story about his early experiences in politics. He first ran for the provincial legislature in 1979 as an NDP candidate, lost, then ran again in 1983, also unsuccessfully. “I would knock on doors,” he recounts, “and sometimes, people would open the door, look at me and just shut it without even saying hello. When I ran again in the ’91 election, no doors were shut in my face. I [could] see some level of acceptability.”

He attributes the shift in attitudes to the election, in the interim, of Moe Sihota, B.C.’s first South Asian member of the legislative assembly. Something else happened in those years; the Mulroney government more than doubled its annual immigration target, pushing it north of 250,000 newcomers a year, well above the Trudeau era. Overwhelmingly, these newest waves of immigrants settled in the suburbs around Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton.

Given the country’s historical ambivalence toward non-white newcomers, it’s tempting to conclude that such a sharp pivot — Mulroney justified the move in terms of the need for more labour — might have ignited another backlash. However, precisely the opposite occurred.

For decades, the proportion of Canadians who felt there were too many immigrants had far exceeded those who thought there weren’t enough, according to years of longitudinal social surveys conducted by the Environics Institute. Through the 1990s, though, when Canada stuck to the 250,000 level set by Mulroney, those attitudes flipped abruptly, with a steep spike in the number of people who disagreed that Canada had too many immigrants.

The explanation is elusive, but it’s not simply a matter of the country having reached a demographic tipping point, says Environics Institute executive director Andrew Parkin. “The views of non-immigrants shifted, [and] immigrants don’t tend to have different opinions than non-immigrants on these questions.”

“It’s hard to measure the impact of these things,” Dosanjh says of the Environics surveys. “It’s very difficult to extrapolate event versus attitude. But it happened, right?”

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement