Love in Another World

Even in familiar surroundings, falling in love can be an otherworldly experience. Imagine how it must have been for those who fell in love—or wished they could—in what was, quite literally, another world.

For centuries, hundreds of young men arrived on North America’s shores—from France and Britain, or later from Japan and China—in search of souls or gold or simply employment, and found themselves consigned to a lifestyle that was, to all extents and purposes, monastic. In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European colonies and trading posts or in nineteenth-century Asian work camps, men outnumbered women by proportions that left many in almost constant need of a cold shower. The circumstances leading to this imbalance and the innovative responses it generated warrant at least a moment’s contemplation in this, our month of amour.

In Canada, the French appear to have both created and remedied the problem first. Beginning in the early 1600s under Samuel de Champlain, the French sent young adventurers, transient craftsmen and, after 1615, zealous Récollet and Jesuit priests to work in North America for periods ranging from a year to a lifetime. Champlain’s initial interests were in furs and a route to China. The twenty-eight men who accompanied him on his first foray up the St. Lawrence River in 1608 were mainly adventurers, among them his sixteen-year-old servant, Etienne Brûlé. The young man, who was notable for his promiscuity, earned the condemnation of the Catholic church for his many liaisons with the sexually tolerant Wendat, the people the French called the Huron.

But though his indiscriminate approach to love would be echoed by others in the centuries ahead—including the Nortons on Hudson Bay in the early eighteenth century and HBC governor George Simpson a hundred years later—Brûlé was not typical of the majority of newcomers to North America. More characteristic were the lasting relationships forged during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by the Cadots (later generations spelled it “Cadotte”) of New France and by Isaac Batt and his descendants in Rupert’s Land.

But a little background is needed. Champlain soon changed his focus from adventuring to colonizing, but despite his efforts Quebec numbered fewer than a hundred people by 1627. And in a preview of the gender imbalance that would plague New France for decades, fewer than a dozen of these permanent residents were women. Determined to step up the rate of settlement, Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister to France’s Louis XIII, established the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, a group of 100 French merchants and aristocrats committed to the development of New France. But the fledgling colony was beset by problems. War with the English in the 1620s and with the Iroquois in the 1640s and 1650s greatly detracted from New France’s allure as a place to build a stable future. Though strongly encouraged to settle in North America, the majority of French soldiers or tradesmen sent to Quebec generally hastened home as soon as their term of service expired.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Perhaps more important, the main business focus of New France (beyond saving souls) was the fur trade. And to the dismay of the Jesuits, this uniquely North American endeavour was soon converting substantial numbers of young Frenchmen to Algonquin or Wendat or Ojibwa ways, rather than the other way around. Life in le pays d’en haut, the vast “upper country” inland and upriver, was seductively free of colonial constraints and religious authority, and captivatingly full of maidens who had all the skills a fur trader could possibly need as well as important connections to the very people who provided the furs. Little wonder that despite myriad dangers and colonial censure, the lure of life as a free trader, or coureur de bois, enticed many to abandon the land and form lasting relationships with Indigenous North American women.

In the colony’s earliest years, when furs were to be had relatively near at hand, or later, when the Iroquois War cut off the supply of furs from Huronia, a number of young farmers managed to combine summers on the land with winters in the woods. By the late 1650s, however, having defeated or destroyed the region’s Indigenous nations, the Iroquois had turned their attention to New France itself. In 1660 and 1661, nearly two hundred settlers were killed as tiny Montreal was besieged and communities near Quebec were pillaged. Both farming and trading came to a virtual halt, and a stream of transient workers fled the colony for France.

The total population of the colony at this time, according to author and historian Christopher Moore, was barely 3,000, when to the south there were 100,000 settlers in the New England colonies and 10,000 in New Holland on the Hudson River. More than a third of the French colonists were children under fifteen. And though historian Yves Landry has established that males outnumbered females by about six to one, the proportion of eligible females, those of age and unmarried, was much lower. At a time when there were more than five hundred marriageable men, there appear to have been fewer than fifty eligible women.

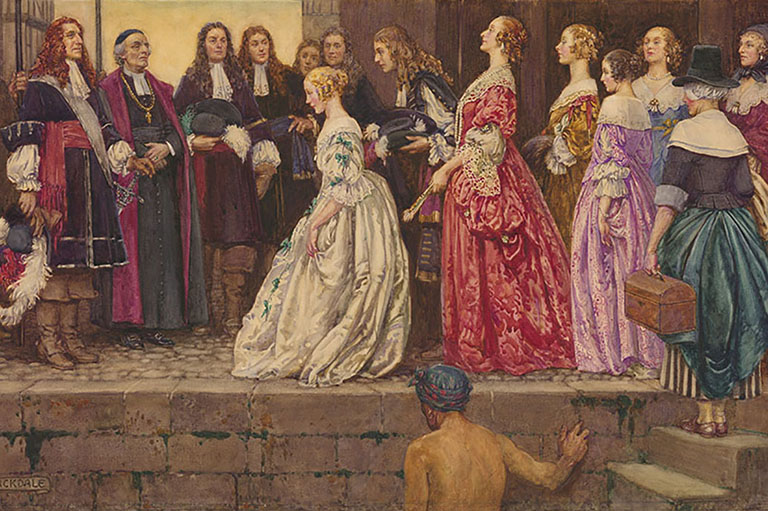

For a young man seeking a wife, the future seemed bleak. Yet within three years, entire shiploads of young women were arriving at the port of Quebec, determined to build a new life, with a new man, in a new world.

What caused this dramatic change? First, the Cent-Associés was disbanded. New France became a royal colony under the direct control of Louis XIV, an astute and determined twenty-five-year-old who would soon earn himself the title “Sun King.” The young monarch could see that if young men were to be induced to stay in New France, they needed wives, and if young women were to be enticed to the colony, it needed to be more substantially defended. His response was twofold: a massive recruitment of young women for New France, and a substantial reinforcement of the beleaguered colonial militia.

The story of les filles du roi, (“the King’s daughters”—though in truth many were almost the same age as Louis XIV himself), is a remarkable chapter in the story of New France. For eleven years, between 1663 and 1673, 770 young women were recruited for the sole purpose of providing wives for the single men of New France. The recruits were given passage to Quebec, room and board for a brief time on arrival, and a dowry of fifty livres, a sum equal to about two-thirds of the annual wages of a hired labourer or engagé. Unlike their prospective mates, who were largely from rural France, the filles du roi were mainly urbanites, and a larger proportion of them (perhaps 30 percent) were literate. These differences in background and education apparently caused few problems; for the most part the young women (nearly a third of whom were from Paris) quickly adapted to the life in a far-off colonial outpost.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Most accepted the king’s offer for reasons of poverty or lack of family and opportunity, but a few were true adventurers. Though they were young, between eighteen and twenty-five, they clearly understood the terms of the arrangement and approached the task of finding husbands in a brisk and businesslike manner. Their contracts encouraged them to marry as soon as possible, within weeks if feasible, and many did just that. Fully 90 percent were married within six months of arrival, but this rapid coupling was not without consideration, according to Marie de l’Incarnation, the founder of the Ursuline convent at Quebec, where many of the young women were accommodated on arrival. “The first thing the girls inform themselves about,” she wrote, was whether or not their prospective suitors were settled with a farm. “And they are wise to do so,” she opined. She knew, as did the girls, that settled men generally made superior husbands.

Remarkably, at least in light of statistics on marriage breakdown today, less than fifteen percent of these rapidly arranged unions were terminated. And of the ninety-five marriages that were annulled, eighty of the women involved quickly remarried and seven of these eventually married a third time. Of the 770 filles du roi, only thirty appear to have returned to France and just one, Madeleine de Roybon d’Alonne, remained single in New France. She died, unmarried, in Montreal at the age of seventy-two. Descended from minor French nobility and a celebrated adventuress, Madeleine had been unusual from the beginning.

Overlapping the filles du roi recruitment program was the arrival of more than a thousand soldiers in the Régiment de Carignan-Salières who were sent to Quebec in 1665 with orders to invade Iroquois territory. Though the damage they inflicted was minimal, the campaign was the final straw for the Iroquois, at least in the short term. Weakened by military losses and devastated by disease, they agreed to a treaty in 1667 that brought peace to the region for twenty years and allowed the newly arriving maidens to focus on the business at hand. They laid to their task with a will, producing offspring at an annual rate of fifty-five to sixty-five births per thousand (a “natural” rate of increase —i.e., without artificial restraints on population—is considered to be between thirty and forty births per thousand, while Canada’s rate hovers around eleven births per thousand today). The result was to significantly increase the population of New France, and in the process lay the foundations of Canada’s francophone population.

By 1681 the population of New France had jumped to more than ten thousand, the majority of them habitants or peasant farmers. Young men coming of age in this peaceful rural atmosphere began to look farther afield for opportunity and freedom from colonial restraints. For many, the answer lay in the fur trade, but unable to obtain a congé or licence to trade (since the colonial government wanted both to control the trade and keep the boys at home), a substantial number turned to illicit trade and became coureurs de bois. Adventure, freedom, and the possibility of wealth beckoned, and soon young Quebeckers were heading by the hundreds west to the Upper Great Lakes.

In 1672, the number of free traders on the Straits of Mackinac was estimated to be between 300 and 400. Eight years later there were at least 800 and perhaps many more, for as one official in New France wrote, “I have never been able to ascertain the exact number because everyone associated with them covers up for them.”

There, in the heart of Old Michigan, these young traders found Ojibwa and Odawa wives. Prefacing another notable mixed-blood community that would evolve more than a century later in Manitoba, the cultures and nationalities merged into a new people—the Métis—who would effectively open much of North America to the fur trade.

The family of Mathurin Cadot embodied much of this history of New France. Travelling to Sault Ste. Marie as a youngster in 1670, Mathurin found he loved the life, and for fifteen years, he traded illicitly before obtaining a congé in 1686. The licence allowed him the freedom to hire others to do the trading, while he married and settled down to the life of a habitant near Trois-Rivieres. Three of his sons followed suit, making trips to Michilimackinac on the strait between Lakes Huron and Michigan, then using their fur-trade profits to purchase cleared land in Quebec.

But the family tradition of farming held no attraction for the eldest of the third generation of Cadots, Jean-Baptiste. In 1742, at eighteen, he signed on with a fur-trading concern on the shores of Lake Superior and quickly found that life in the pays d’en haut suited him perfectly. He learned to speak Ojibwa and married Anastasie, the daughter of a well-known Ojibwa chief, in Ste. Anne’s Church on Mackinac Island.

With a foot firmly in both camps, the Cadots played a significant role in many of the key political and military events over the next forty years. In the 1750s, he was a mediator and interpreter for the French in the Sault Ste. Marie area; she was active in conducting the trading operations in his absence. A decade later, at the end of the Seven Years’ War, the Cadots played host to the New England trader Alexander Henry the Elder for a winter. By the 1760s, Jean-Baptiste was representing British interests in the region, and earning enough from trading to be able to afford to send his wife and three children to Montreal, where the youngsters were educated. Finally, in the mid-1770s, Cadot, Henry, and several other merchants took a brigade of canoes all the way northwest to the Saskatchewan River, beginning a trend that would lead to the fur trade’s most ruthless competition period.

Anastasie died in 1776, but the couple’s children finished their education in Montreal before returning to the Sault. Both Jean-Baptiste Jr. and Michel (both used the spelling “Cadotte”) followed their father into the fur trade, and in 1784, the senior Cadot was named to Michigan’s first board of trade. In 1785, the family firm sent more than 36,000 livres worth of furs back to Montreal, and succeeding generations worked in the fur trade for another fifty years. Clearly, unions between French or Canadian men and Indigenous North American women could result in social, political, and economic advantages.

In the posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the situation was very different.

One of the first bayside governors, Henry Sargent, brought his wife and family, as well as her female companion and the family chaplain, with him when he took over at Moose Factory and Fort Albany on James Bay in 1683. Though Mrs. Sargent made a valiant effort at creating a speck of domesticity in the North American wilderness, the experiment marked the only English attempt at settlement in Rupert’s Land for nearly a century and a half. In fact, the London Committee soon bent the other way, engaging youths on the cusp of manhood and expecting them to remain celibate during terms of up to seven years service. Not only were women not allowed to accompany their men to “the ould Nor’Wast,” but the “Company servants,” as hired employees were termed, were actively discouraged, even disciplined, if they were found consorting with Cree or Dene women at the bayside posts. They were, in short, expected to be virtual monks. And those who did have relationships, and children, were expected to abandon them when their term of service was over.

Yet the services of the women (beyond any sexual involvement) were absolutely essential to the smooth running of the company’s affairs. They served as cultural and linguistic interpreters; they trapped small game and fished (and on more than one occasion were responsible for providing the only food available at a post, thus saving the men from starvation). They sewed moccasins, netted snowshoes, and made pemmican. They prepared the skins for shipment and often made beautiful clothing. They cleaned and washed and, in later years, cared for large gardens at many posts.

Not surprisingly, the regulations ordering celibacy were rarely obeyed, and company officers, serving long terms of employment, were often the worst offenders. Anxious to retain those who could stand the rigours of a long tenure on the bay, the London Committee was forced to turn a blind eye to these indiscretions, creating a hypocritical two-tiered system. Three generations of the Norton family shed light on the complications created by the HBC’s explicit, implicit, and illicit regulations.

Richard Norton, who began his career as a thirteen-year-old apprentice with the HBC in 1714, displayed a talent for languages that soon drew attention to him. Mentored by Thomas McCliesh, then governor at York Fort, Norton eventually married McCliesh’s daughter Elizabeth in England. But Elizabeth was forced to stay behind when Richard returned to the bay, apparently to a Cree woman he had earlier partnered. Over the years, as he rose to become governor at Churchill, Richard apparently had a series of liaisons, not only in North America but perhaps in England as well. In 1739, the committee was forced to acknowledge his Cree partner in Churchill, though it quibbled about providing for her and her children.

These complicated relationships did not prevent the company from hiring Richard’s son Moses, born out of wedlock, though whether to a Cree mother or a mistress in England is not clear. Moses must have been either reasonably well educated or astute in business, for he too rose to become governor at Churchill, and outdid his father at promiscuity. A rather jaundiced Samuel Hearne described Moses’s family circumstances as a “harem,” comprising “five or six of the finest... girls which he could select.”*

Despite his distaste for Moses, Hearne (who succeeded the Nortons as governor at Fort Prince of Wales) fell head over heels in love with his favourite daughter, Mary. Her “benevolence, humanity, and scrupulous adherence to truth and honesty,” wrote Hearne, “would have done honour to the most enlightened and devout Christian.” Alas, when Hearne surrendered the fort to the French in 1782 and was taken prisoner, Mary, like many of her Cree relatives, starved to death the following winter. Returning to the plundered fort, Hearne wrote bitterly that she had perished “a martyr to the principles of virtue.”

Mary was, it seems, truer to her Cree roots than the members of her mother’s harem. According to a number of contemporary observers, Cree women (and therefore most Cree marriages) were noted for monogamy. Though Cree marriage ceremonies were simple, wrote William Falconer, an officer at Severn House in the 1760s and 1770s, both husband and wife “performs their dutys, and are more chaste to each other than the more civilized Nations who are instructed with the Dutys of Christianity.”

Unlike the Nortons, many English and most Orcadian employees of the HBC also were single-minded about their relationships with Indigenous North American women. Their “country marriages”—according to the custom of the country, à la façon du pays - often lasted for life, and eventually the HBC recognized its responsibility in supporting these fur-trade families. By the 1790s, the company had also recognized that if it provided education for the offspring of these unions, it could develop its own pool of uniquely qualified talent, both male and female.

One who displayed such marital fidelity was Isaac Batt, an Englishman who arrived at York Factory in 1754 and within two years took a Cree wife. Batt became one of the company’s most widely travelled traders, and his wife travelled with him until he was murdered in 1791, one of a very few HBC employees to die violently at the hands of others. Their daughter, Nestichio (in Cree her name, suitably, means “three persons in one ”), was raised to be at home in both cultures. Some time in the 1780s, she married an Orcadian, James Spence.

By the late 1700s, the HBC was largely staffed by Orcadians, a group well known for its industriousness and sobriety. Less well known perhaps is that Orkneymen also distinguished themselves by their marital fidelity, as the Spences and their descendants illustrate.

Nestichio and James had four children before James died accidentally at Buckingham House in northeastern Alberta in 1795. After his death, HBC governor William Tomison, another Orcadian, saw to it that his widow and the children were provided for under the terms of Spence’s will. She never married again, but lived a long life that eventually took her to Red River (now Winnipeg). Her descendants moved to all parts of the continent.

Though their circumstances differed substantially, young French and English men both had at least some opportunities for choice when it came to selecting a wife in North America. And the women they met and married also had options. Those options were considerably more limited for the Japanese men who began to arrive in Canada in the 1880s and 1890s and the women who followed them between 1908 and 1928.

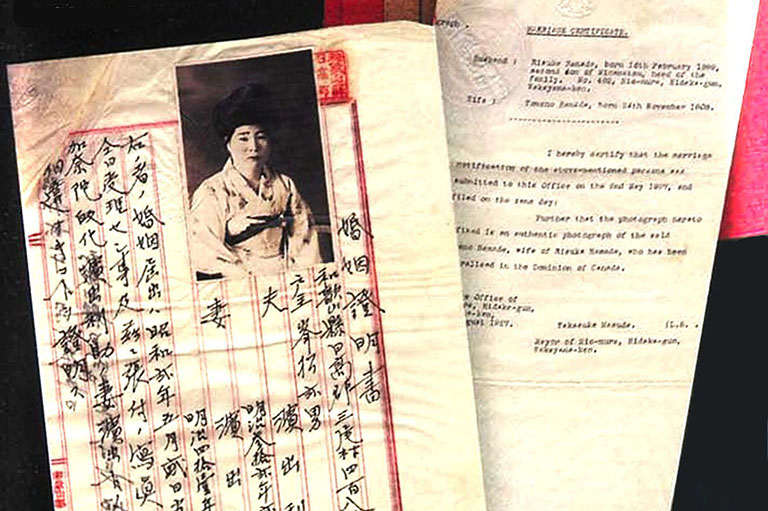

The dekasegi rodo—“temporary migrant workers”—were constrained by several things: the values of the samurai culture in Japan, which stressed filial piety and duty rather than love and affection; a belief in the importance of Japanese racial purity and cultural isolation; and the racial discrimination and lack of opportunity that the largely unilingual workers faced in work camps on Canada’s west coast. But as it turned out, the dekasegi were aided in finding a solution by Japan’s Meiji educational system, which gave girls a compulsory education aimed at producing tractable young women who would obey first their fathers, then their husbands, and eventually their sons. With this background, thousands of these women willingly became Canada’s “picture brides.”

In the beginning, the dekasegi mostly came to Canada expecting to work for a number of years on the railways or in the canneries or logging camps and then return home with their earnings to marry and raise a family. But low wages, miserable living conditions, and the temptations of gambling and drink prevented many from raising the necessary capital to return to Japan. By the early years of the twentieth century, the number of single Asian males in British Columbia was causing tensions, which culminated in a major riot in Vancouver in 1907. The government’s response was twofold: to limit the number of new workers and to allow wives or potential wives to immigrate.

The result was the picture bride or shaskin kekon—“photo marriage”—system, in which prospective newlyweds exchanged photographs and married by proxy prior to her emigration. Not only did the young women have to submit to marrying someone they did not know, a familiar circumstance in a country where marriages were often arranged by families, but they had to endure this new life in a strange country far from home, in hostile white communities where they didn’t speak the language. The remarkable thing is that a substantial number of the nearly seven thousand picture brides who came to Canada did so by choice. While fathers or elder brothers did force many young women to accept this fate, the majority, according to a recent study by Midge Ayukawa, played an “active role in the decision to marry and emigrate to ‘Amerika.’” All recognized that spinsterhood was unacceptable in Japan, some felt that emigration offered opportunities unavailable at home, and a few were simply looking for adventure. For them, the hardship and discrimination were balanced by opportunity. They “married Amerika, not the man.”

It was nevertheless a difficult transition. The men were often poor, sometimes ignorant or even brutal. The conditions were frequently appalling. Children were born in lonely shacks without assistance, a stark contrast to the family-centred birthing situation in Japan. But the young women had been trained to deal with these circumstances. Meiji women strove to be “modest, courageous, frugal, literate, hardworking, and productive.” Many laboured at day jobs, even when their children were young, to provide the means to educate them. One, the widow of a fisherman, took over his boat until her eldest son was old enough to get a fishing licence. Another ran the family inn when her husband died.

But a number refused to put up with the hardship or domestic abuse that sometimes resulted, instead striking out on their own. One such was Kiyoto Tanaka-Goto, whose story was included in Ayukawa’s “Good Wives and Wise Mothers,” an article in BC Studies. She arrived in Canada in 1914 as a nineteen-year-old picture bride and laboured with her first husband, Mr. Tanaka, on farms in Duncan and on Saltspring Island. Hoarding every penny, she saved enough to leave her husband after four years, and went to Vancouver where she purchased a bawdy house with three other Japanese women. They converted it into a successful restaurant and bar. Later, she moved to Kamloops and was briefly married to a Mr. Goto. Eventually returning to Vancouver, she ran another business until 1942, when Canadian officials attempted to place her in a detention camp. Refusing to be forcibly detained, she was sent to prison instead. On release she masqueraded as Chinese and slipped back to Vancouver, well ahead of the return of most Japanese in 1949. Clearly, Kiyoko Tanaka-Goto was anything but a tractable Meiji woman.

On balance, though both the methods of finding a partner in the “New World” and the results of those couplings were many and varied, the thousands of successful unions point to the universality of the human condition. No matter that geographically, culturally, and linguistically a prospective mate might be literally from another world, the power of love, combined with commitment and caring, could span the globe.

“The Most Beautiful Girl in Red River”

John Peter Pruden, retired chief factor for the Hudson’s Bay Company, was a man accustomed to being obeyed. The exception, apparently, was his lovely daughter Caroline, a child of his late middle age who inherited his independent spirit. As she grew to womanhood, her father, undoubtedly wary of the reaction she created among members of the opposite sex, became particularly stern.

There were certainly enough young men to go around, for in 1846 (when Caroline was fifteen), the British Government sent 500 soldiers of the Sixth Royal Regiment of Foot to Red River causing great excitement in the community. In the spring of 1848, a ball was held at Lower Fort Garry, a gala affair, according to Dr. John Bunn: “Polkas, gallops, waltzes, quadrilles, cotillions … reels and jigs, employed the heels and talents of the assembly,” he wrote. And Caroline Pruden, along with Margaret and Harriet Sinclair, were the belles of the evening.

Many years later, Harriet Sinclair Cowan wrote that “Caroline Pruden was the most beautiful girl in Red River and she kept her beauty all her life.” But the ball of 1848 was memorable for another reason, she recalled. “The polka was new. Somebody had just brought it from New York. There was a great deal of talk about it … and Mr. Pruden … had forbidden Caroline to dance it [though] her stepmother said she saw no harm in it. But Mr. Pruden came to the door of the ballroom … and when he saw Caroline dancing it, he stood there scowling and waiting. The moment the dance was ended, he held up his finger to her and said ‘Miss Disobedience, come here’ and he made her put on her wraps and made his wife come too and drove home with them.”

The incident didn’t dampen Caroline’s spirits, for two years later, following her marriage to Thomas Sinclair, a well-to-do freighter and son of Chief Factor William Sinclair, for her honeymoon she travelled by York boat to York Factory, the only woman with a brigade of men. Among the goods transported back to Red River were the bells for St. Andrew’s on the Red. At their first overnight campsite on the Hayes River, the boatmen took the bells, hung them from the highest tree in the area, and rang them in honour of the beautiful bride.

—Robert Pruden and Barbara Huck

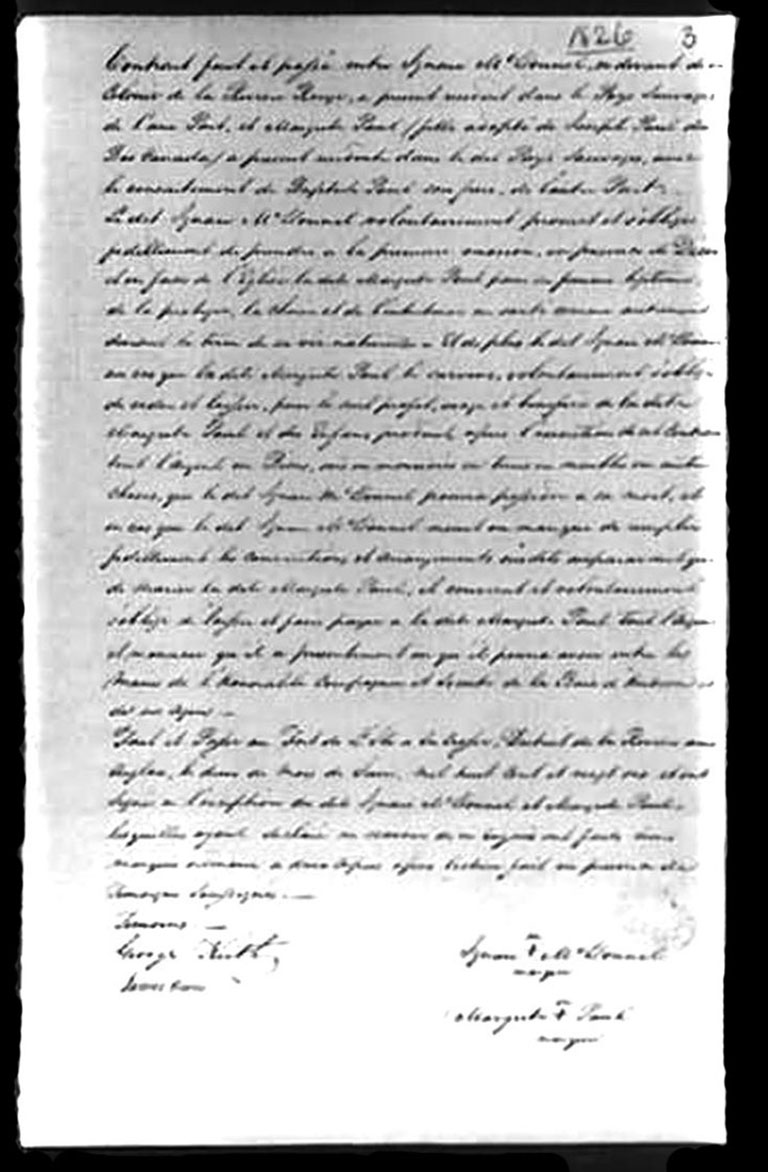

A Marriage Contract

Though at first the Hudson’s Bay Company forbade unions between traders and Indigenous women, it eventually saw the benefit to accepting them. Marriage contracts such as this, which became common after the HBC merged with the North West Company in 1821, formalized the “country marriages” of the past, giving wives legal protection and ensuring that husbands fulfilled their financial responsibilities. Such marriages were sanctioned by the civil authority of the Hudson’s Bay Company through their chief factors, in this case George Keith, who was in charge of the English River department in northern Saskatchewan. With the coming of Christian missionaries, a clause was added requesting married couples undergo a religious ceremony when a clergyman became available.

The marriage contract shown here, between a Hudson’s Bay Company trader and his native wife, reads as follows:

This contract was made and agreed to between Ignace McDonnel, formerly of the Red River Settlement, now resident in the Indian Country and Margrite Paul (adopted daughter of Joseph Paul, from the Lower Canada) and now residing in the said Indian Country with the consent of Baptiste Paul, her brother.

The said Ignace McDonnel voluntarily promises and swears faithfully to take, at the first opportunity, for legal spouse the said Margrite, before God, to protect, to cherish and to maintain her in health as in sickness, as long as she lives. Furthermore, and in the case Margrite Paul survives him, the said Ignace McDonnel voluntarily swears to give and leave, for the only profit, usage and benefit of the said Margrite Paul and of the children born after the execution of this contract, all moneys or possessions, in currency, in land, in furniture or others, that the said Ignace McDonnel may posess at his death. In case the said Ignace McDonnel dies or fails to fulfill faithfully the conventions and dispositions aforementioned, before marrying the said Margrite Paul, he agrees and voluntarily swears to give and to transfer to the said Margrite Paul all currency and money that he now owns or that will own, in the hands of the Honourable Hudson Bay Company and Society and of its agents.

Made and signed at the Fort Ile a la Crosse, in the English River District, on the second of the month of June, eighteen hundred and twenty-six and signed except by the said Ignace McDonnel and Margrite Paul, who said upon enquiry that they did not know how. They placed their normal mark on two copies after listening to the reading in presense of the witnesses who signed this contract.

Witnesses

George Keith

James Heron

Ignace McDonnel

X

Margrite Paul

X

*Sir George Simpson, governor of the HBC from 1821 to 1860, was also known for his promiscuity and for abandoning a series of women and at least five children, including those of his country wife Margaret Taylor, much to the dismay of his more honourable subordinates. In the autumn of 1830, when Simpson returned to Rupert’s Land from Britain following marriage to his eighteen-year-old cousin, Frances, it is said that Margaret Taylor was literally whisked out the back door as his new wife entered the front.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!