Peacetime Killer

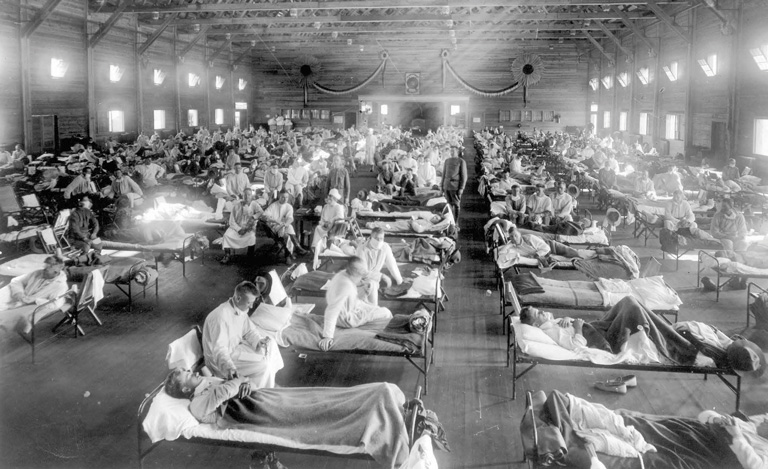

On October 5, 1918, military officials hastily moved fifteen ill Canadian soldiers travelling through Calgary on a Canadian Pacific transport train into an isolation unit at a nearby army base. A thoroughly nineteenth-century approach to disease containment, the quarantine didn’t work, and Calgary was soon inundated with infected civilians.

Only a few days after the train incident, Toronto Western Hospital found its wards rapidly filling with ill patients. Across the city at the Toronto Grace Hospital, run by the Salvation Army, fully half the nursing staff was ailing by the middle of October.

The town of Sydney, Nova Scotia, had been virtually shuttered, its theatres, dance halls, and schools ordered closed in the days after the sudden deaths of three American servicemen stationed there.

Public and official sentiment had changed swiftly over the course of just a few weeks.

While many Canadians were well aware of the Spanish influenza epidemic sweeping through the wartime trenches and post-conflict demobilization camps in Europe and the United States, some Canadian authorities initially insisted that this wave of grippe, as the disease was also known, didn’t differ markedly from the annual fall flu outbreak.

Yes, a young girl had died in Toronto in late September — the first recorded civilian death in Canada — and many people had come down with colds. But as the Globe noted on September 30, 1918, “no alarm is felt by the Toronto health officials.” The reason? “The measures which people themselves took” to avoid getting sick.

As the fall wore on, however, that sanguine outlook crumpled in the face of far darker reports that ricocheted across the country. The disease, which would kill fifty-five thousand Canadians and up to one hundred million people worldwide, spread along east-west rail corridors, travelling with soldiers returning from the war or heading to fight in Siberia.

As it leapt into civilian populations, the Spanish flu ripped through families and communities, especially poorer ones. Like a hurricane, the pandemic left a trail of seemingly random and abrupt tragedy, as well as the long social and economic aftermath caused by the deaths of so many young, healthy people. The young turned out to be especially vulnerable to this particular virus.

In Montreal, trolley cars were hastily converted into rolling hearses to accommodate the tide of flu victims headed for burial, according to a 2003 account of the pandemic by federal Minister of Science and Sport Kirsty Duncan, then an adjunct professor of anthropology and geography at the University of Toronto.

In Hamilton, cabinetmakers worked around the clock to keep up with the demand for coffins. Celebrated author Lucy Maud Montgomery contracted the flu in October. She returned to Prince Edward Island in a morose and physically weakened state, only to watch her beloved friend and cousin Frede Campbell succumb to the virus.

In her book Hunting the 1918 Flu, Duncan relates a story of two young Ontario women — roommates who had attended a lecture when the epidemic was at its height.

“In the morning, Claire Hunter called to her friend in the same room, ‘Vera, I’m going downstairs for breakfast.’ There was no response. After breakfast, Claire returned to her room to get her purse and again called to her roommate. No answer. This time, Claire pulled back Vera’s sheets. Vera was dead. The doctor said that she had died at about two in the morning.”

At a sprawling military base for the Polish army in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, the disease jumped easily from soldiers to the local civilian population because people were constantly coming and going, according to Wilfrid Laurier University’s Kandace Boegart, an anthropologist-historian and the Kleghorn Fellow on War and Society. After the pandemic erupted, she said, “the camp tried to close” its gates, but the attempt to restrict access came too late.

Improbably, the flu worked its way into the most remote locations, from Innu settlements in Labrador to tiny outposts on the West Coast. James Allan Evans, a retired University of British Columbia classicist, recounted in a 2000 essay the story of a family of six living in “complete isolation” on an island between Vancouver Island and the mainland.

“With no contact with the outside world, they should have been safe from the virus.” When both parents fell ill, they piled their four children into a boat and headed out across choppy ocean waters toward Alert Bay on Cormorant Island. The father died en route; the mother died a few hours after they landed.

Meanwhile, in Manitoba, the flu was spreading north, likely as the result of “an elaborate network of train lines, roads, and water routes” that fanned out from Winnipeg, as social scientists Lisa Sattenspiel and Ann Herring noted in a 1998 study.

The epidemic, they found, “overwhelmed” some Cree and Métis settlements in the vicinity of a handful of Hudson’s Bay Company outposts, including Norway House, where the mortality rate exceeded one in ten by December.

“The disease is raging in Pelican Narrows,” a newspaper in The Pas, Manitoba, reported regarding an HBC outpost just over the Saskatchewan border. “In one house, there were 20 [people] lying on the floor helplessly sick, with four dead bodies lying among them.”

“The disease,” Sattenspiel and Herring wrote, “hop-scotched across the landscape, leaving most family groups intact while ravaging and even extinguishing a relatively small number of others.”

But for the fact that many members of those Indigenous communities were out on traplines in late fall and early winter, the devastation would have been far greater, the authors concluded. Other communities weren’t so fortunate.

A 1967 study estimated that the pandemic killed almost four per cent of Canada’s Indigenous population — a mortality rate five times greater than among the general population. Some especially remote communities that had no health-care resources were wiped out entirely.

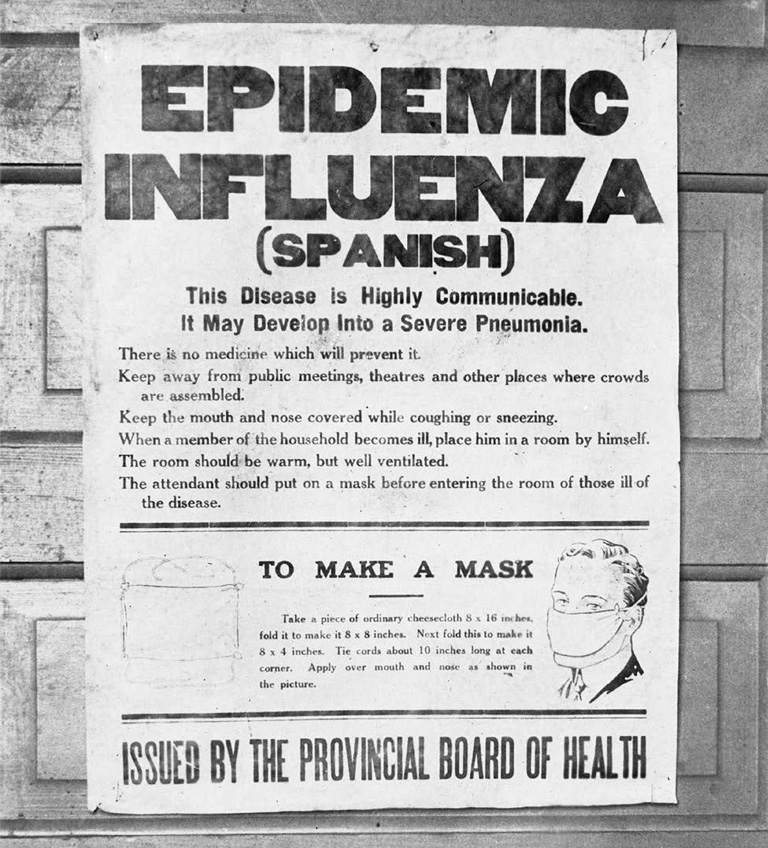

With sickness and death infiltrating every corner of Canadian society, ordinary people reached for anything that promised some kind of protection, even as health officials recommended the use of cotton masks and the avoidance of crowded places. Duncan describes measures such as sacks worn around the neck containing mothballs or cotton balls soaked in camphor.

The sick, many of whom had developed fierce and often lethal pneumonia, were treated with “poultices of goose grease, bran, lard and turpentine and compresses of fir tree spills, mutton tallow and mustard,” according to Duncan.

Meanwhile, in the Quinte region of eastern Ontario, readers of Weekly Ontario learned that an apparently fail-safe remedy for the “thin” blood and “weakened” nerves associated with the flu was essentially snake oil — a concoction produced in Belleville and known as Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People.

As the newspaper reported, the treatment contained “just the elements needed to build up the blood, and restore the lost colour and vitality.” The cost: fifty cents a box, or six for $2.50.

By the early spring of 1919, it seemed as if nothing had been left untouched by the pandemic, including the Stanley Cup playoffs, which were taking place that year in Seattle in late March. In the middle of the finals between the Montreal Canadiens and the Seattle Metropolitans, several players on each team contracted the flu, and one died on the eve of the fourth game. The series was abruptly cancelled.

Very soon after, the pandemic — by then in its third wave — petered out, receding almost as quickly as it had arrived. Now, a century later, it is both fascinating and instructive to ponder the elusive lessons of an outbreak that killed more people than any other similar event in history, including wars and plagues, and yet rapidly receded from collective memory.

We spent the early years of this century, living in looming shadow of some devastating future pandemic. After the outbreak of SARS in 2003, and H1N1 in 2009, health officials in many countries started planning for the sort of major global pandemic that has occurred every thirty years or so over the past century. Those emergency management exercises in some places have proven to be vitally important. In others countries, but especially in the U.S. under President Donald Trump, critically national security planning efforts to prepare for major pandemics were scrapped for political reasons.

In many ways, the 1918 Spanish flu represents the nightmare scenario, frequently invoked, if not well understood, and certainly well beyond the reach of living memory. However, the rapid and devastating spread of Covid-19, moving within a few months in early 2020 from a food market in China’s Wuhan region to virtually every corner of the globe, has provided a harsh refresher on what it’s like to live through a viral hurricane.

But when flu historian Mark Humphries, director of the Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, talks about the legacy of the Spanish flu pandemic, he is quick to offer a caution: Beware of comparisons, because 1918 and 2020 are profoundly different when it comes to infectious disease control and health.

An adult who lived through the Spanish flu, he said, would have grown up at a time when outbreaks of tuberculosis, yellow fever, polio, smallpox, cholera, and typhoid were hardly uncommon. Indoor plumbing, water treatment, sanitation, hygiene, milk pasteurization — these were all relatively new technologies, especially in a country that tended to lag behind the United States and Europe in public-health policy.

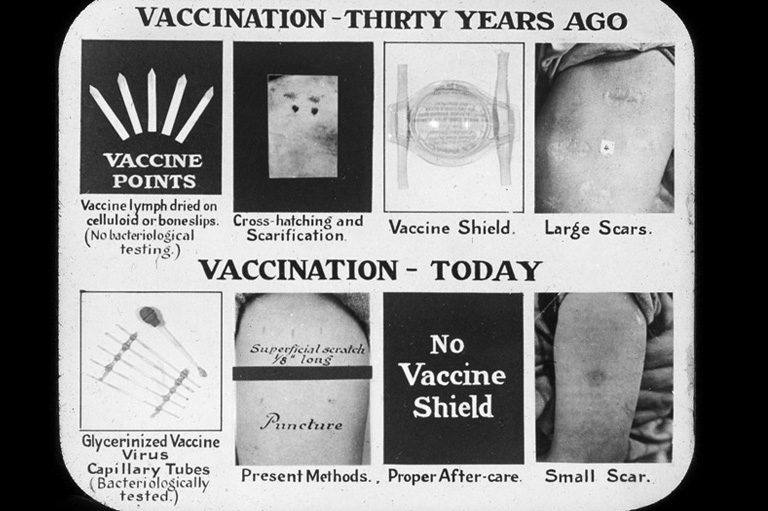

While rudimentary vaccines existed in 1918, Sir Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin — which, in various synthetic forms is now routinely used to treat most infectious diseases as well as pneumonia, one of the leading causes of death in the 1918 pandemic — was still ten years off. The flu virus itself wouldn’t be isolated until the early 1930s, and antiviral drugs, now routinely stockpiled and used in wealthier nations, didn’t appear until the 1950s. Life-saving devices like ventilators, though in critically short supply during the Covid-19 crisis, obviously didn’t exist, which meant more people didn’t survive the pneumonia that is perhaps the most lethal byproduct of infectious viral diseases like H1NI. (A 2008 paper by the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, in Washington, D.C., found that bacterial pneumonia was not only responsible for most of the deaths in 1918-1919, but would likely be a major factor in future flu pandemics.)

That same adult, moreover, likely had a far lower baseline of health and a shorter life expectancy than she would have today, Humphries added. Coal was the primary fuel source, causing polluted air and the resulting lung irritation. For many people, their diets lacked sufficient fresh fruit and vegetables and other important sources of nutrition.

“I would argue that what the flu did, at a time when the major nineteenth-century epidemic diseases were coming to an end, was remind people how susceptible they were.”

While no one was immune, some people were more susceptible than others. University of Manitoba historian Esyllt Jones has written extensively on the Spanish flu.

She points out that the poor, recent immigrants and the members of isolated Indigenous communities tended to be more vulnerable, even though the flu virus — unlike infectious diseases linked to poverty — didn’t pay attention to class lines.

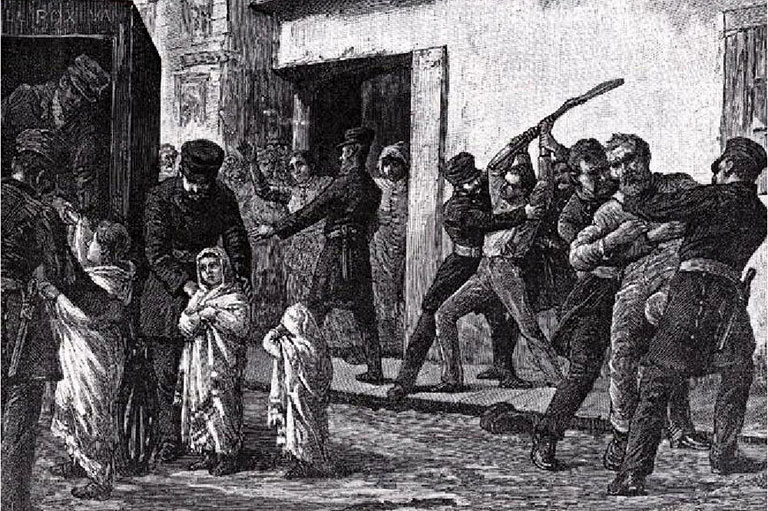

During previous epidemics, public health officials often used coercive measures, such as quarantines and placarding homes with official signs indicating the presence of sick people, to isolate those who were infected — measures that were often inflicted on poor communities that were more likely to experience the overcrowding, contaminated water, and other conditions that accelerate infection.

By 1918, however, a growing number of municipal health departments had abandoned these tactics, instead deploying small armies of nurses and volunteers to visit and to treat sufferers in their homes. Toronto’s public-health nurses paid more than seventeen thousand home visits during the outbreak.

Some of the two thousand nursing aides in the Canada and Newfoundland Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) also joined this effort upon returning from Europe to Canada, having treated flu-stricken soldiers in France and, in some cases, having come down with the disease themselves.

Nurses kept patients “calm, hydrated, nourished and rested,” observed Linda Quiney of the University of British Columbia’s school of nursing.

Despite this outreach, Jones added, “influenza threatened the fragile framework of survival for many working families, but it also created among immigrants and working-class communities a heightened awareness of their mutual reliance and their ability to sustain themselves in times of crisis.”

For example, in Winnipeg’s North End, home to the city’s Jewish community, the Yiddish-language press promoted fundraising campaigns to support afflicted families. “There was a sense that it wasn’t appropriate for them to be seen to not be able to take care of their own,” said Jones, who sees such efforts as indicative of a newcomer community’s awareness of its own vulnerability.

Such examples of grassroots local support cropped up in many communities across the country, according to Boegart. “With pandemics, you get the best and the worst. There was a lot of volunteerism, and people taking care of their neighbours.”

Hundreds of kilometres north of Winnipeg, as the flu swept through remote Indigenous settlements, different communities had starkly different experiences.

University of Toronto medical anthropologist Karen Slonim observed that at Norway House, a predominantly Cree HBC outpost north of Lake Winnipeg, federal officials dispatched a physician and two assistants for two months to treat flu sufferers.

But at Fisher River — a settlement on the west side of the lake and actually much closer to the city — the residents received little federal aid, relying instead on local medical attendants and a hospital. It’s not clear from the records why the response varied so widely.

As Slonim found when studying medical records, the epidemic proved to be far more devastating in Norway House, which was also experiencing food shortages and plunging temperatures when the disease struck. Fisher River, situated much farther south, had a more agriculturally based economy.

Yet in both communities, she observed, “the traditional way of life had been irrefutably altered, and the systems that once enabled people to deal with hardship or catastrophe had been decimated.”

Jones points out that the epidemic cast a similarly long shadow over some urban neighbourhoods, particularly in working-class families where the primary male breadwinner died, leaving his spouse to pick up the pieces. Unlike the partners of soldiers killed in battle during the First World War, flu widows received no pension, although some received a modest mother’s allowance.

Many ended up raising children on meagre welfare payments, forced to justify their household budgets to visiting social workers, whose case files formed the basis of Jones’ research. Remarriage was very rare. Rather, the children raised in these households faced enormous pressure to leave school and to start working as soon as they could.

“Influenza was a source of downward social mobility,” Jones explained. “It had a long-term socio-economic impact, like the war itself, but flu survivors had no benefits.”

Gauging the wider impact of the 1918–19 Spanish flu has been a preoccupation of historians, public health experts, and anthropologists for years. It is a surprisingly elusive problem, in part because the historical narrative of the pandemic was either subsumed by the nation-building mythology of the war or forgotten.

Historian Alfred Crosby, author of America’s Forgotten Pandemic, said the major writers of the period — Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, F. Scott Fitzgerald — barely mentioned the flu, even though they’d personally encountered its devastation. (One of the best-known accounts is a powerful 1939 novella by Katherine Anne Porter, Pale Horse, Pale Rider.) The pandemic’s speed “encouraged forgetfulness,” he added. “Many people thought of the flu as simply a subdivision of the war.”

Unlike the war effort, however, there was scant postwar public commemoration of the heroes of the pandemic, and specifically the hundreds of nurses who attended to victims and often caught the disease, sometimes dying from it. In the emotion of the immediate aftermath, plans were drawn up to erect memorials to the doctors and nurses who fought on the front lines of this scourge.

But, in the end, according to Quiney, only two VAD nurses who died of the disease, Dorothy Twist and Ethel Dickinson, were recognized. “There was a brief moment when women were supposed to get medals and were spoken of as heroes,” Jones observed, “but it didn’t last.”

There’s no question that they were heroes. Twist, who had served in a British military hospital but died of the flu while working in Surrey, B.C., is recognized on two cenotaphs on Vancouver Island, including one in her family’s hometown.

Dickinson, a Newfoundlander, did a two-year VAD stint in London, England, before returning to St. John’s in poor health in the summer of 1918. Like Twist, she contracted the virus while attending to ailing soldiers in a local hospital, and she died within two days.

A memorial cross in her honour was erected in 1920 in St. John’s and acknowledges the contribution Newfoundland nurses made during both the war and the epidemic. By contrast, First World War memorials, cenotaphs, plaques, and other markers can be found in almost every city, town, and school in Canada.

Mark Humphries offered a different view of the issue of memory of the pandemic. “It got lost not because people forgot about it but because of the many [diseases] around then that could kill you.”

While he was doing research on the flu early in his career, he recalls excitedly arranging to interview his elderly great-grandmother, who’d been nineteen in 1918.

While he was eager to hear about her experiences with the flu outbreak, she was far more interested in talking about the smallpox outbreak of 1921. “She had forgotten about it because it had been overshadowed by other things.”

Yet Jones observed that when she gives public lectures about the flu there’s invariably plenty of evidence that private memories of the flu persist through the generations. Audience members offer handed-down anecdotes about grandparents or other ancestors. “The notion that we forgot [the pandemic] just isn’t true.”

How did those private experiences translate into public action? The answers vary widely. There’s no specific evidence establishing a link between the pandemic and the Winnipeg General Strike in the spring of 1919, but Jones argues that the hardships endured by flu-ravaged working-class or immigrant families helped to stoke the sense of unrest.

In other domains, both in Canada and abroad, the connections between the pandemic and subsequent events are far clearer. In the decade following the pandemic, scientists in the United States and the United Kingdom set to work trying to identify the cause of the disease, conducting research that eventually led to the isolation of the virus.

In South Africa, meanwhile, the pandemic provided local and national white politicians with an excuse to cement land-use-planning laws that institutionalized racial segregation in the name of public health, reasoning that such outbreaks flourished in poor communities with many black residents and poor sanitation.

Here in Canada, the most specific policy response to the flu was the decision by Prime Minister Robert Borden’s Conservative government to establish a federal department of health regarding a policy field that had been managed by most municipal and some provincial governments as far back as the cholera outbreaks of the 1830s.

Pressure to make this jurisdictional incursion had come from public health practitioners and organizations like the Ontario Medical Association.

In fact, at a May 1919 symposium at the University of Toronto, convened by the Canadian Public Health Association and other groups, speakers called on the federal government not only to establish a national department of health but also to invest in influenza research and to establish a public-health insurance system, a reform that didn’t happen until the early 1960s.

Humphries said the new department’s initial mandate was broad and included labour standards, housing, immigration, infectious-disease reporting, and quarantines. “It very quickly lost steam,” he added.

In a matter of a few years, and absent another pandemic, the department devolved into an information clearing house and a forum that allowed the federal government to work with provincial public-health officials.(Prime Minister Paul Martin’s government resurrected the notion of a federal public health agency in the aftermath of SARS. That decision proved to be highly proactive during the Covid-19 crisis, with Dr. Theresa Tam, the chief public health officer of Canada, playing a highly visible leadership role in determining the national response.)

The creation of the federal health department also came on the heels of years of activism by social reformers and Progressives whose broad modernizing agenda included everything from improved sanitation to prohibition. Canada, what’s more, had lagged the United States and Europe when it came to social-welfare and public-health policy.

The calls for a federal agency, in fact, reflected a thoroughly twentieth-century belief that this responsibility required the heft of a centralized bureaucracy and national standards. The pandemic, Humphries explained, amplified the urgency of such demands and galvanized figures such as Dr. Charles Hastings, Toronto’s crusading medical officer of health and one of the country’s leading proponents of public-health advocacy.

Indeed, perhaps the most important legacy of the 1918 pandemic is that it marked the waning of the thinking that had dominated Canadian public-health practice for generations: that the vector of infectious diseases could be halted using isolation, exclusion, and sanitary reform. (The approach didn’t disappear entirely: In the United States, Mary Mallon, known as Typhoid Mary, was quarantined for the last twenty-three years of her life because she had been identified as an asymptomatic carrier.)

As Jones points out, because the flu was just as likely to strike affluent communities as to strike poor or immigrant ones, and because it spread extremely rapidly across large distances, traditional containment methods simply didn’t work. (Local officials nonetheless continued to post notices on the doors of ill families.)

Instead, during and after the pandemic, medical officers of health turned to prevention-minded public-education campaigns, treatment, and, eventually, vaccination campaigns.

“The federal department of health,” concluded Humphries, “laid the basis for a new ideology of public health governance, one that saw disease as a community problem, not only an individual hardship or a plague brought on by outsiders.”

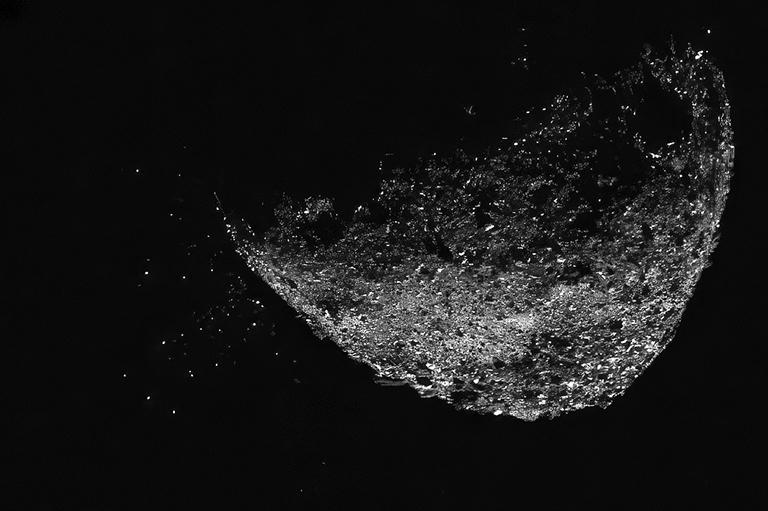

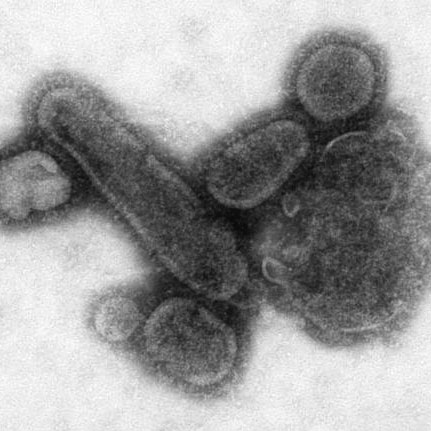

DEATH BY DROWNING

The virus that caused the Spanish flu, one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, is related to the modern H1N1 strain. The 1918 virus killed about 2.5 per cent of those infected, compared to a more typical rate of 0.1 per cent for previous flu outbreaks. (The mortality rate for Covid-19 is in the 4-6 per cent range.)

Named for the widespread death caused in Spain by an early wave of the disease, the virulent 1918 strain may have originated with a genetic shift in the flu virus in China.

Many of the afflicted thought they simply had a cold, which progressed to the usual flu symptoms of fever, diarrhea, aches, and fatigue. Pneumonia often followed. The illness moved with grim speed — it wasn’t uncommon for sufferers to be dead within a day of first showing symptoms.

Unlike other epidemics, the Spanish flu was most deadly for those in good health between about twenty and forty years old. The virus caused a reaction that seemed to turn healthy people’s immune systems against them. Victims’ lungs filled with bloody, frothy liquid and their faces turned blue as they drowned in their own fluids, suffocating from a lack of oxygen.

— Nancy Payne

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!