The Lepers of Tracadie

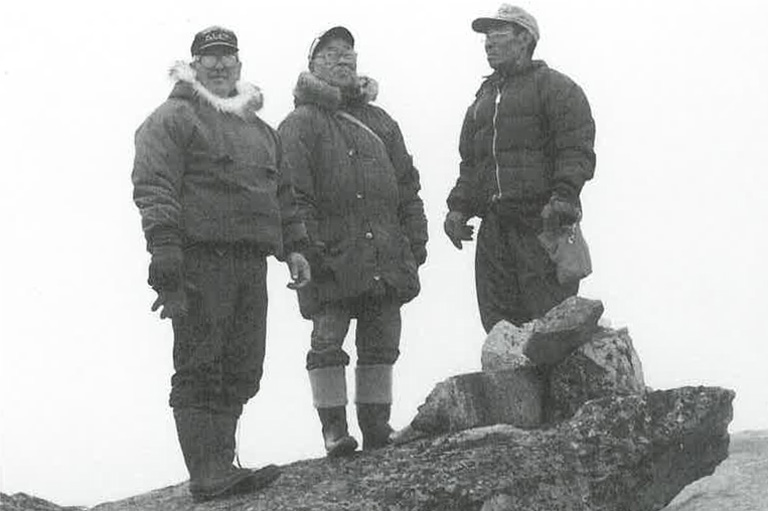

What is most moving about the nineteenth-century photographs of the French-Canadian lepers of Tracadie is that the subjects are often dressed carefully in their Sunday best. Despite their ruined faces and missing noses, facial growths and tumours, the little girls and women have tied white bands in their hair; the men wear ties and waistcoats.

We think of leprosy as a far-off tropical disease, certainly not a Canadian problem. But these lepers, some of the last inmates of the leper hospital in Tracadie, New Brunswick, were Canadian victims of one of history’s most feared diseases.

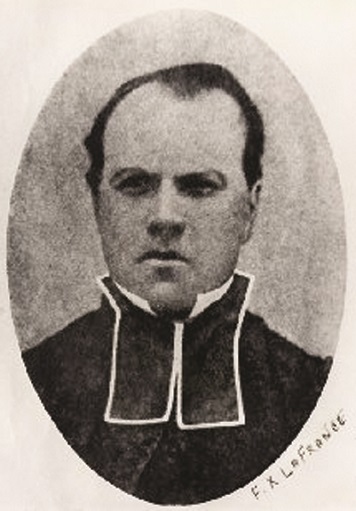

In 1844, Francois Xavier Lafrance, a young priest newly arrived in the northeastern New Brunswick fishing community of Tracadie, reported a horrifying discovery. Some of his parishioners were disfigured by a “loathsome disease.” Their faces were distorted with fleshy lumps and swellings; noses, hands, and feet were ulcerated and gangrenous, with bones showing through gaping wounds. Their breath was foul and voices husky as the disease invaded their throats. Some were blind.

Responding immediately to the priest’s urgent request, New Brunswick authorities dispatched a medical commission. In their report, the doctors confirmed Lafrance’s suspicion: The villagers were suffering from leprosy, a slowly progressive, often-fatal, skin- and nerve-destroying disease — “identical with the tubercular leprosy which prevailed throughout Europe during the Middle Ages.”

Older settlers helped the commissioners pinpoint the first case. Ursule Benoit, an Acadian woman, had showed signs of leprosy in 1817, dying of the illness in 1828. The commissioners heard the gruesome story that at Benoit’s funeral the liquefying contents of her casket leaked onto the bruised shoulder of a pallbearer, who subsequently contracted leprosy and died. Since then, cases had been appearing in the region. In their 1844 report, the commissioners identified eighteen still-living victims.

Leprosy has been feared throughout history. In the Middle Ages, lepers were deemed “unclean.” A still-living leper would be given a funeral mass, declared dead, and banished from the community.

In keeping with this grim tradition, the commissioners ordered the afflicted men, women, and children — some as young as eight — rounded up and segregated in an old cholera quarantine station on Sheldrake Island, located at the mouth of the Miramichi River, approximately eighty kilometres from their homes. There, virtually abandoned, the lepers were to live out the remainders of their lives.

Sheldrake leper colony was no hospital sanatorium. The quarantine sheds were airless, dark, cold, and dirty. Medical care was non-existent. The less crippled were expected to care for the more mutilated.

Conditions rapidly deteriorated. One visiting doctor described the horror of the scene in 1849: “I never saw a spectacle more calculated to harrow the feelings of humanity. The stench was so intolerable from putrefaction that it required the greatest determination even to undertake … treatment.”

The French-Canadian leper colony attracted much medical attention at a time when the quarantining of lepers had become highly controversial. A series of searing articles in the medical literature was critical of New Brunswick’s handling of the situation.

“The crimeless sufferer has been condemned by the legislator of his country to perpetual imprisonment,” wrote Canadian physician Dr. Robert Bayard in an article in The Lancet.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Doctors such as Bayard thought quarantine was unnecessary because the disease was too rare to be transmissible. Leprosy had existed for twenty-eight years amongst the 22,000 residents of two New Brunswick counties, yet only forty cases had ever occurred. And close contact between diseased and healthy people was common. Babies were often nursed by “leprous mothers” and lepers slept with healthy spouses.

For instance, a man named Fabien Gotreau was described as having been diseased for three years, with tubercles on his genitals. Yet he cohabited with his wife, who remained well, as did their seven children.

An article by Dr. Alexander Boyle in the London Medical Gazette in 1844 pointed out that New Brunswick was far behind the times for its practice of isolating people in leper colonies.

“[For Europe], greater experience has banished all dread of its supposed contagion, and opened their noble hospitals to the admission of lepers, without distinction, among other patients,” wrote Boyle.

Boyle and others argued that leprosy was hereditary. They produced genealogies linking the New Brunswick cases to Ursule Benoit’s family. They believed hereditary predisposition, combined with poverty, poor sanitation, and bad food, in particular “putrid fish,” could activate latent disease.

Others disagreed. Dr. Alexander Key, who had led the 1844 New Brunswick medical commission, was convinced leprosy was transmissible and that lepers should be incarcerated.

As we know today, both views are partly correct. Leprosy, or Hansen’s disease, is indeed caused by an infectious organism, Mycobacterium leprae. But as the Canadian medical writers so clearly documented in their studies, leprosy is difficult to transmit. Most populations are extremely resistant, and the risk to others is small. Only about one percent of those exposed will ever develop full-blown leprosy.

Unhappily for the Acadians of the nineteenth century, the New Brunswick government was under intense public pressure to confine the lepers. General apprehension drowned the more moderate medical voices. The unfortunate leprosy victims were left to decay in their medieval-style lazaretto.

Conditions for the New Brunswick lepers slowly improved as the century wore on. A new institution was built in Tracadie in the 1850s. Dr. James Nicholson became the lazaretto’s first resident doctor in 1863. And in 1868, seven Montreal Sisters of St. Joseph — including pharmacist St. Jean de Goto — arrived in the colony. The sisters’ compassion, nursing care, and attention did much to alleviate the suffering of the imprisoned residents.

The source of leprosy in New Brunswick remains a mystery. Some historians believe the organism may have been carried by Acadian exiles returning from Louisiana, yet another tragic by-product of the expulsions from Acadia that began in 1755. Alternatively, it may have originated in Normandy.

However the disease arrived, it took a hundred years before leprosy burnt out in the population. The last Acadian patients were admitted to the leprosarium in 1937; the facility closed in 1965.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Leprosy today

There may be more cases of leprosy in Canada today than were incarcerated at any one time in Tracadie’s leprosarium. In the nineteenth century, the facility held only thirty to forty inmates at a time. But between 1979 and 2002, in Ontario alone, 184 cases of leprosy were reported, mainly from countries where the disease remains entrenched, such as India, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

Leprosy is still an infectious, transmissible disease. It is curable, but curing people is difficult. The patient must take several powerful drugs for a long period of time. Yet leprosy goes largely unnoticed in Canada.

One important reason we no longer fear this disease is because the frightening terms “leprosy” and “lepers” have been retired. Today the malady is renamed Hansen’s disease after Armaur Hansen, a Norwegian who discovered the causative bacillus in 1873. The loss of the word has helped us lose the horror that once condemned so many to be isolated and abandoned.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!