Tragedy at Crooks Inlet

My Uncle Annugaq was sixteen years old when most of his village died. This happened in 1937 at Kangitujuaq, 146 kilometres west of Kimmirut (Lake Harbour). This area is also known as Crooks Inlet.

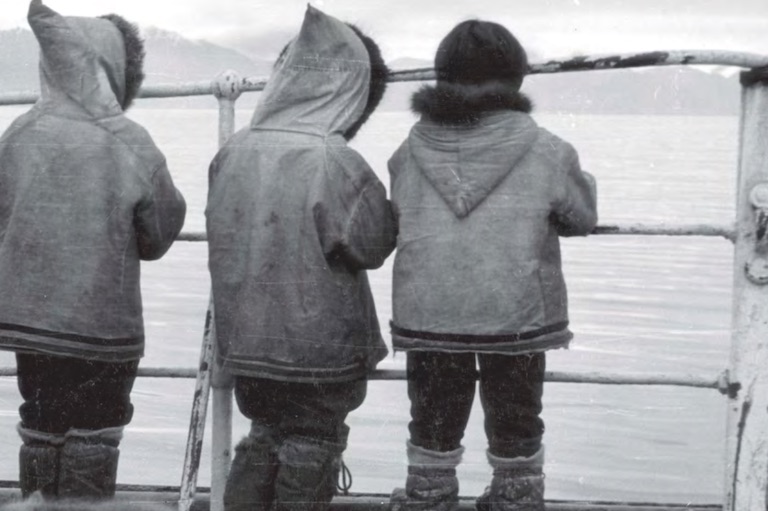

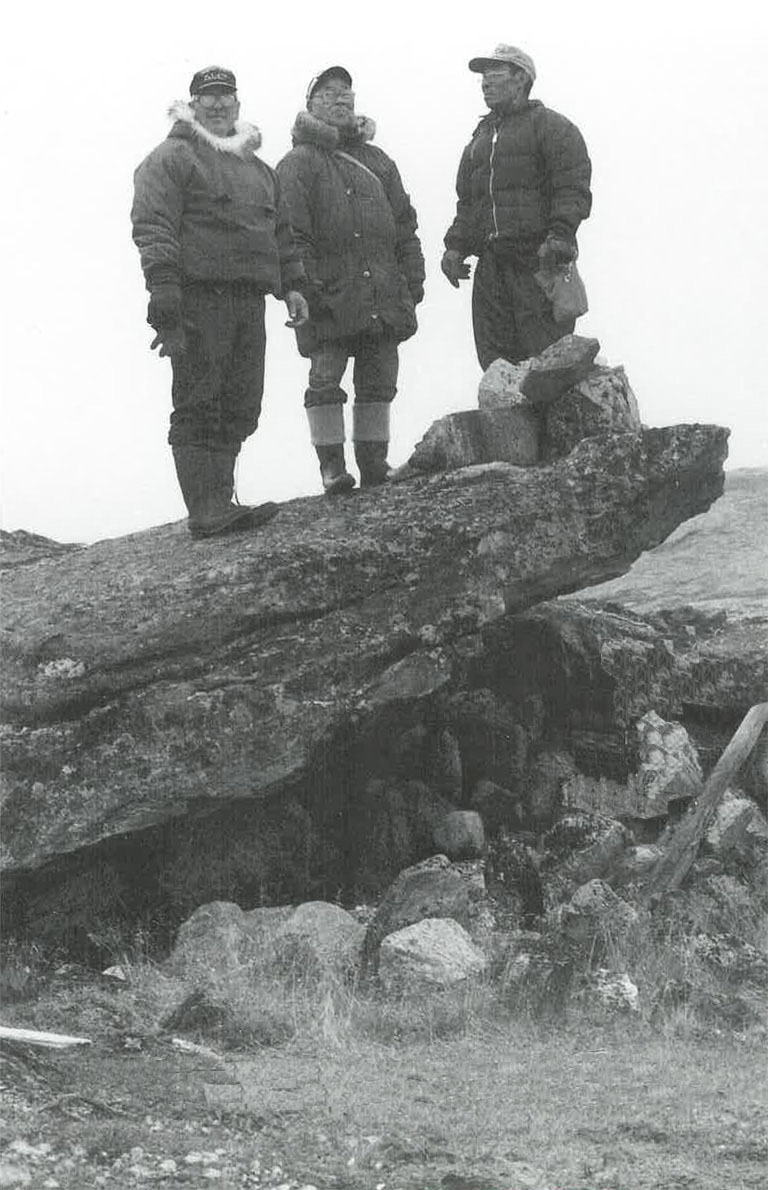

My uncle told me this story in bits and pieces over the years. To make the story whole, I asked him if he wanted to go back and see the burial sight. When he indicated he was ready, we flew to Kimmirut in the summer of July 1998 in a Twin Otter, a half-hour ride from Iqaluit.

We spent a day planning our trip with Sandy and Ineak Akavak, who had agreed to take us. Since my uncle did not remember having any kind of Christian burial for all those who died, we wanted to take a minister to say prayers with us. Taqialuk Timilaq, an Anglican lay reader, readily agreed, and packed his Bibles.

The boat trip to Crooks Inlet took just over one day. My uncle recognized many places he had not seen for over sixty years, citing who had lived here and there, remembering the leaders of that time. He shared his memories with Sandy and Taqialuk as we listened in the background. We did not hear everything as the gentle roar of the motor muffled their voices.

When we reached our destination, my uncle led us to a huge, isolated boulder that was protruding toward the sea. There, in its hollow part, were human bone scattered all over the place: skulls, legs, rib, arms, and hands.

The wooden headstone had fallen from its place and lay on top of its subjects. We observed each name on the wooden pole. The names were hard to read because the wood had long been weathered.

From memory my uncle recited the names; we repeated them after him. Reciting the names out loud made it more real that they once existed and lived on this earth: Ipivik, Iola, Manumi, Pitalusi, Jaimisi, Musi, Alika, Josipi, Pitsiulaq, Sandy, Agusimajuq, Nakasuk, Palluq ...

After observation and respect, we had a memorial service, led by Taqialuk. He read passages from his Bible and prayed. After his prayers, we mourned the dead as if it just happened yesterday, not in 1937.

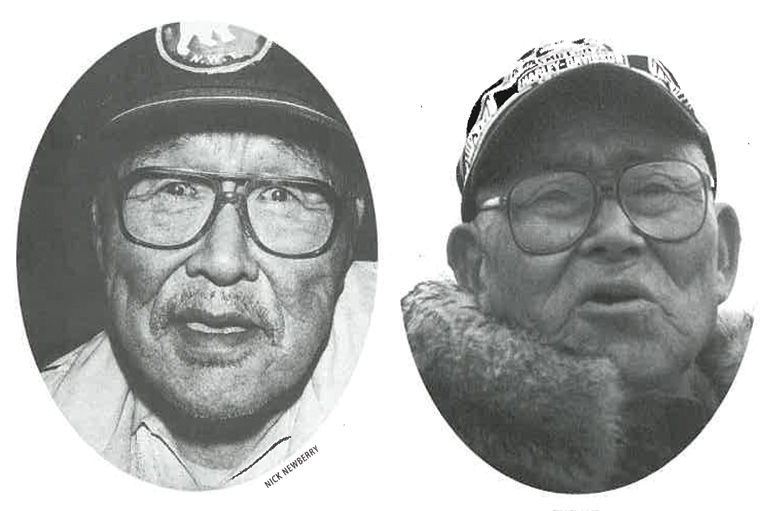

Uncle Annugaq

This is my Uncle Annugaq’s story, translated from Inuktitut:

In the winter of 1937 my mother Palluq told me to go and stay with my sister Josie and her husband Meekitjuk for the remaining winter. They lived closer to Kimmirut at the time. My mother said I would have more to eat at my sister’s. We were going through hunger times in our village that winter.

Iola passed through our village with his dog team. I took a ride with him to Takijualuk, my sister Josie’s and her husband’s temporary camp, near Kimmirut. It was as if I were fleeing from a terrible fate because shortly after, there were many sudden deaths. It was only about one month or even less after I left all these deaths happened. It seems I fled from all these deaths; it was not my time.

Ajunaqmaat [It cannot be helped].

I cannot say where their pain started when they got sick. I only have heard that the beached whale was suspected. The people ate from this beached whale. People have said if a beached whale is bloated and rotten, it can be blamed for the deaths. It has never been proven, it has been only suspected. No one knows for sure.

My father Arnaquq went through the unimaginable, as their leader and family member, as he watched his mother Pitalusi, wife Palluq, two sons Iola and Pitsiulaq, and his older daughter get sick and die on the same day!

My great-uncle Isaacie and his family were the only ones not affected. They did not get sick. My uncle Johnnybo, the son of lsaacie, was the one who went to get help from Kimmirut when he was so young.

The survivors from our family were my father Arnaquq, two sisters Mialiralaq [Little Mary], Annie, and our cousin Annie Shoo. I survived because I was moved out of that village before it happened, as if to flee the tragedy. It was meant to be that I stay alive. Today I have reached old age and I am grateful.

I remember there were five qamma [huts]. Our village was called Niaqunguu, a big hill shaped like a head. There were few villages along the coast of Kangitujuaq. They were far from each other. They were usually one day travel by dog team.

We are so grateful to Pita, the clerk. I am so grateful to him. I have had no opportunity to thank him personally.

I know he went through a lot. I know it is a lot to bury one person but he had to bury so many all at once. When one person is being buried, many mourn. At that time, so many died! They were poor and yet one person worked so hard to bury them and put them to rest! We are so grateful to all those who worked so hard. We have not had our opportunity to voice our gratefulness.

It has been over sixty years. I used to hunt rabbits, ptarmigans, trap foxes near the burial sight. I could see it with my eyes. I could not go near it. I could not go near it alone. I wanted to go near it. I had my fox traps almost near it on purpose so I could someday work up the courage to go near it.

When I became an adult and [was] living in Iqaluit, I was almost ready and was able to utter I was ready. My only reason was I had no means of getting there. It was so far from Iqaluit and there was never any appropriate time. Then I would think I had to go and there was no other way about it. I could go by snowmobile or boat. I would tell myself I would not go alone. There would have to be people around me.

Uncle Johnnybo

Johnnybo Ulluakallak was seventeen years old when he had to make a journey he would never forget. He admits, at over eighty years old today, he forgets what happened yesterday and yet has a good memory from long ago. He is frail now, has loss of hearing in both ears. He talks gently and almost inaudibly at times. When he describes the time he had to go and get help while he was still able to, he livens up to unfold the tragedy.1

This is his story:

My same-named one Johnnybo2, Jaimisi, and lpivik went hunting to the floe edge at the Big Island. They were to spend the night there.

The next day a lone dog team was approaching our village. They [the three hunters] had left with two dog teams the day before. We were watching them as they got nearer and nearer. I remember it was a very nice clear day.

Jaimisi dismounted from the sled. He put his right hand over his eyes as he knelt with his left knee. The dogs did not stop. They continued to approach our village.

It was the time of longer days. It was pleasant to be outdoors. We were outdoors enjoying the pleasant weather when we received the bad news. The whole village was crying as we learned what had happened. Jaimisi’s brother lpivik had died. He got sick, then died the next day!

Soon after, Jaimisi got sick. My same-named one Johnnybo and I were told to go and get help from Kimmirut. There were no nurses or doctors at the time. There was the RCMP and the Hudson’s Bay Company post.

We always knew and admired Jaimisi’s dogs for their strength, alertness, and speed, but this time they did not want to pull. They were very down and sad.

The RCMP officer was Papikaaq [Cpl. H.A. McBeth], his coworker was Iritajak, and their guide and interpreter was Tommy Mitchell, from Labrador.

Papikaaq and his guide prepared their dog team and started for our village as soon as they learned what was happening. We followed them, but our team was so sad, we could not keep up. When we finally got to our village, almost everyone had died. They had died so quickly. There were few people left: Pitsiulala, Kallajuk, Mialiralaq, Annie, and Annie Shoo.

It was not a pleasant place to arrive to. All the huts were occupied by the dead people.

There were no more dogs. They had all been shot; otherwise they would have eaten all the dead bodies.

The few survivors were gathered to one place. Then after a while, they were moved to another village. In our household, no one got sick or died. My cousin Anniqniq, Ipivik’s widow, moved in with us because she had lost all her family.

Soon after all the deaths, Aqpik [a relative from another village] moved us to another place. We had no more dogs.

I don’t know where the pain started when they got sick. They died so quickly.

We were going through [a] hunger period that winter. The hunting was poor.

There was a beached minke whale. People ate from this whale. Some suspected that this caused their illness and death. Soon after they ate from this whale, they had uncontrollable diarrhea. They were not even aware of their bowel movements or the desire to eliminate.

In our household, we did not eat from this beached minke whale3. In our family, there was my father Isaacie, my mother Shuvinai, sisters Mitiq and Avvirut, and my younger brother Yuu.

Pita the Clerk

There was another person who went to help the people in that village, a young twenty-two-year-old Hudson’s Bay Company clerk, Mr. Peter Nichols (who my Uncle Annugaq refers to as “Pita the clerk.” “Pita” is “Peter” in Inuktitut). Mr. Nichols and I started to write letters back and forth in the spring of 1999. He sent me a transcript of an interview about the events at Crooks Inlet, which resides in the Hudson’s Bay Archives:

The one event that took place at Lake Harbour during my stay there and which had a considerable effect on me was an epidemic that broke out at an Eskimo community in Crooks Inlet, some hundred miles from the Lake Harbour post4.

It all started just before Christmas when two small boys who could not have been more than eight or nine years old arrived one evening at the post with three dogs and an empty komatik5. They were almost frozen.

They reported to the store manager, Mr. Wilderspin, that at their camp at Crooks Inlet, there were a lot of sick Eskimos and some had already died. Mr. Wilderspin made as much inquiry as he could a to what was the cause of it all, but the boy themselves really couldn’t say much except that everybody was hungry because with the sickness it meant that none of the hunters could leave the camp and obtain food.

Immediately, Mr. Wilderspin decided that he would send me to Crooks Inlet with a load of supplies and to find out just what the problem was. The next morning, I left with my dog team and an Eskimo companion, and we proceeded to Crooks Inlet, spending two nights on the way.

When we arrived at the camp, to my horror I discovered that during the days since the boys arrived at Lake Harbour, fourteen Eskimos had died: men, women, and children. The others were very, very hungry, having no food and not being able to get any because of their illness.

Some of the Eskimos that were able had collected together the fourteen bodies of the deceased and placed them in a sealskin tent which had been covered with snow blocks. The bodies were frozen.

The dogs, by the time I arrived, were ravenous, had broken into the tent, and were feasting on the bodies of those who had already died. The first thing we did was destroy all the dogs as there was no possible way that we could feed them. We had dog food for our own team but this was needed to get us back to Lake Harbour.

After destroying the dogs, the next was to try and establish what the problem was and what the epidemic consisted of, and also to feed those who were still living. I remember making a large pot of oatmeal porridge because one of the traits of the epidemic was that the throats of the people affected were constricted, so they had great difficulty swallowing, and it was almost impossible to get solid food down their throats. But a gruel made of oatmeal seemed to be able to slip down fairly easily.

One thing that affected me greatly was that in trying to spoon-feed one of the Eskimo men, he died in my arms.

We stayed at Crooks Inlet for two days. By that time we were running short of supplies and there had been further deaths. There was nothing that I could do — or nothing I thought I could do — to prevent further deaths.

Those who survived seemed to have passed the worst of the epidemic and I thought they might just make it. So it was decided that we should evacuate those remaining and take them all to Lake Harbour where we could better look after them.

Meantime, it was important that we try and establish the cause of the epidemic and what it really was. I made inquiries from the survivors as to what they had eaten prior to the outbreak, and one of the things that came up was that a large whale had driven ashore not far from their camp in the early fall, and they had eaten some of the meat from the rotting whale. It occurred to me that there was a possibility that this might have been the cause.

On the other hand, I couldn’t explain why the epidemic seemed to constrict their throats. It was mainly women and children who survived. The death toll consisted mostly of the older people, but there were some younger people included.

Before leaving for the return trip to Lake Harbour with the survivors, the bodies of those who had died were all placed together in one skin house, the largest that was in the place. They were all frozen and left there. The skin house was then covered with snow blocks to prevent, if possible, any animal from breaking in. The dogs had all been killed and it would only be the wild animals that might break in and harm the bodies.

We took off for Lake Harbour with, I recall, possibly twelve survivors, including one very small little girl, who was so small that to prevent her falling off the komatik, we tied her on with sealskin line. We arrived at Lake Harbour safely, and the survivors were taken by local Eskimo families and taken care of.

I then made my report to Mr. Wilderspin and told him all I could possibly gather as to what led up to the epidemic. He then wrote his detailed report to the head office, giving all the symptoms it was possible to pass on, and much later, after the following ship time, we heard that the doctors thought it was internal mumps.

On the other hand, I’ve always wondered myself whether it wasn’t some sort of poisoning, brought about by eating the dead whale. The story continued in the spring.

I had it in my mind all the months leading up to the spring that these bodies were still lying frozen in this tent and something would have to be done for a permanent burial ground.

With the permission of Mr. Wilderspin, in the spring when the ice was still on the sea and the ground was practically bare, with my own dog team and by myself, I travelled back to Crooks Inlet. I found that all the snow had disappeared. The most desolate sight I think I’ve ever seen was this camp, all the snow gone. The sealskin tents which they were using were there of course, still up, but it was like a dead community.

The flapping of the sealskin in the small wind was just a weird experience. The bodies in the sealskin tent were still frozen solid and in the most grotesque shapes, just as they had died and just as they had been carried and placed in the tent. Now it was a question of where to bury them permanently.

I walked around the area of the camp and found in one place a large, overhanging rock. It was not a cave but just a large rock with an overhanging lip and, knowing that it was impossible to dig a hole, I decided that the only way to bury the bodies and protect them from bears and what-not was to lay them all inside this overhanging rock and then carry rocks and close up the entrance.

There was no snow on the land and to move these fourteen bodies from the sealskin tent I had to use the dogs and a sleigh, which meant dragging the sleigh over ground rather than snow and ice. This took considerable time because of the way in which they had frozen; their arms and legs were sticking out all over the place and only one or two could be moved at a time.

They were still clothed, and it took me practically the whole part of one day to move the bodies under the overhanging rock and then another day to gather together sufficient large stones from close at hand and further away. It was well known that the bears can break down most anything and one had to make a very strong entrance if one wished to protect the bodies. So it was finally accomplished.

As a last touch, I’d prepared before leaving Lake Harbour a wooden cross on which, with the help of an Eskimo, I’d inscribed all the names of those who had died6. The last thing I did was to erect the cross over the stone and to fasten it with large stones so that it wouldn’t blow away. I’ve often wondered if that cross is still there.

One other thing that struck me as being dreadful in a way, was that when I arrived at the camp the one living thing that I saw was a little Eskimo puppy with a huge, distended stomach. It was one dog that we might have missed on the earlier trip when it was decided to destroy all the dogs. I tried to catch this little dog. I didn’t have the heart to shoot it, but I tried to catch it because I thought I might take it back to Lake Harbour. But I couldn’t. I eventually left it.

Today in Nunavut, some Inuit are visiting their original homes on the land to relive the memories, to heal the old wounds, to mourn some of the loss of old language and culture, or just to visit the past. I took my uncle to Crooks Inlet so he could finally mourn and bury his grandmother, mother, two brothers, a sister, aunts, uncles, and friends with grace and dignity for the first time. Even if it took over sixty years.

Cause of Death...

The Beaver asked Dr. Ian Wanless, professor of pathology at the University of Toronto and Toronto General Hospital, to infer the cause of death from the facts presented in this article.

The accompanying story describes an outbreak of an illness that affected more than half the members of a village on Baffin Island in 1937. The illness was characterized by the nearly simultaneous onset and rapid death of almost all those who were affected. All the villagers who became ill had apparently eaten flesh of a beached whale that had been dead for months and was frozen in the ice. The illness was associated with severe diarrhea and difficulty swallowing.

The features of this outbreak, including the food source, time course of the illness, and symptoms, are highly suggestive of botulism. Botulism is caused by one of several toxins formed by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum.

The toxins cause paralysis of the skeletal muscles by blocking the release of the neural transmitter acetylcholine. Most cases of botulism occur after ingestion of contaminated food. Symptoms begin within hours of ingestion, and death may occur in as little as eight hours and usually within a few days. Even with modern medical support, the mortality rate is 15 per cent.

Early symptom of botulism are related to weakness of the muscles in the head and neck, with double vision, difficulty speaking and swallowing, drooping eyelids, and dilated pupils. Intestinal symptoms include nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, and diarrhea or constipation. Death occurs after paralysis of the chest muscles prevents the victim from breathing.

Outbreaks of botulism have been reported throughout the world after ingestion of improperly prepared food. The implicated food has generally been allowed to remain at room temperature prior to cooking or preserving. Outbreaks are also common in livestock that have ingested infected silage or carcasses scavenged in the field.

Botulism is endemic in northern regions with incomplete access to electric power, including Canada, Alaska, and Greenland. In Canada, reports for the years 1995 to 1997 describe forty-one cases in nineteen outbreaks with one fatality.

Seventeen of these outbreaks occurred in the Arctic and two in cities. The food implicated included seal (seven outbreaks), fish (four), whale (four), micerak (two), and walrus and pate (one outbreak each).

— Ian R. Wanless, MD, FRCPC

Notes

1. On November 8, 2000, after this article was written, Johnnybo died after many months in and out of hospital in Iqualuit. He appreciated every visit at the hospital and his home at the elders’ facility.

2. There were two Johnnybos, both about the same age. In the lnuk culture, when more than one person are named after the same person, they are known as “my same-named one.” The boys were named after John Bull, an early whaler in the region.

3. There is some discrepancy over the type of whale. Peter Nichols, the HBC clerk, maintains it was a Greenland (bowhead) whale, and that it likely died before the freeze-up in October. The illness occurred in December, just before Christmas.

4. In one of his letters, Mr. Nichols apologizes for using Eskimo because it was the term of the day. He says, “You will note that in the interviews with the HBC archivist I used the word Eskimo rather than Inuit, and I hasten to assure you that no disrespect, whatsoever, was intended. This term was in common use in those early days. During my forty odd years in and around the whole of the Canadian Arctic I had nothing but respect and admiration for the “people” and believe I had many good friends among them.”

5. Johnnybo looked much younger because he was starving. To a healthy clerk, he (and likely his same-named one) must have looked like a little boy, half-starved, poorly clothed, small for his age. Also, we Inuit were not very large at the time.

6. Pitsiula had written the names in syllabics on the wooden cross in pencil and then Mr. Nichols etched them. Pitsiula was the mother of Ineak, Sandy’s wife, who came with us on our 1998 trip.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!