Killer Flu

Bringing the country to a near standstill, a killer flu rampaged across Canada in autumn 1918. Schools, churches, and places of entertainment shut down, business was disrupted, and doctors overwhelmed. At its peak, the flu was so deadly that undertakers and gravediggers could not keep up, and there weren’t enough hearses: caskets were conveyed to cemeteries in passenger automobiles and delivery wagons.

Each death had its tragic tale. Arthur Barton, of Brandon, Manitoba, who joined the army at the age of twenty-four, died on November 5, 1918, just days before the war ended and not long after returning home.

Lieutenant Harry Helliwell of Edmonton got the flu while recruiting dogs in northern Alberta. His wife contracted the illness while nursing flu patients and died a short time earlier. Helliwell was not informed of her death and likely wondered why she was not at his bedside as he died.

Flu victim Donald William of St. Thomas, Ontario, was described by Canadian Press as “one of the most brilliant young barristers of the era, being one of the youngest lawyers in the history of Canada to attain his qualifications, only twenty-one years of age at the time.”

Mr. and Mrs. Quinn of Montreal and their newborn baby died on the same day, leaving a fourteen-month-old as the family’s sole survivor.

Although the 1918 flu originated in China, it was called the Spanish flu because it was first officially recognized as a disease in Spain. History’s most lethal flu, it killed an estimated fifty million (there are no precise figures).

It was one of history’s worst pandemics. (An epidemic is the occurrence of a disease in excess of its expected rate; a pandemic is an epidemic that occurs over a large geographical area, usually considered to be in many different parts of the world.)

Out of Canada’s population of eight million, fifty thousand died from the flu, an enormous death toll in just a few months. In contrast, sixty-thousand Canadians died in the four years of World War I. The Public Health Agency of Canada states the country’s usual death toll from flu is between four and eight thousand.

“Flu kills in many ways, most commonly by causing pneumonia with or without a large immune response that can lead to leaking of fluid, and sometimes blood, from the body into the lungs,” explains Dr. Isra Levy, director of the Office for Public Health at the Canadian Medical Association and an expert in epidemiology, disease control, and community medicine. “A person dies from overwhelming infection or from inadequate oxygenation of the blood.”

Examining how Canada grappled with the Spanish flu provides guidance when facing the threat of another global flu attack. The Public Health Agency states that a flu pandemic is “inevitable,” if not from the bird flu, then another strain. With a global population of 6.5 billion — over three times the 1.8 billion of 1918 — a comparable pandemic would be devastating.

“History repeats itself if we don’t learn from experience,” Dr. Levy points out. “In many respects, we learned the same things from SARS in 2003, as from the 1918 response.”

SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) killed eight hundred people worldwide. Reaction to SARS was swift. The World Health Organization issued a travel advisory against Toronto, a hot spot.

“From both [cases] we learned that it is difficult to make diagnoses in non-specific situations,” Levy says. “It takes a few days to know whether a person has a bad cold or a true flu virus that requires more care and can lead to death. Both times the lesson was learned that to prevent panic it is critically important to provide clear, solid communication so people know in real time what is going on.”

In 1918, as in 2003, it was learned that quarantine is not always feasible or effective because of the resulting stigmatization and the economic damage that results (in the case of SARS, Toronto’s tourism business was badly hurt). Planning needs to be tailored to the local response.

Levy notes one major change from 1918 — disease spreads much faster with today’s jet travel. The Spanish flu originated in China in February 1918 but did not reach Canada until September of that year.

Levy warns, “Today, the rapidity of travel is quite phenomenal, exacerbating the situation. Despite scientific and medical advances, flu remains a bad disease. It takes time to develop vaccines for each strain, and not all antiviral medications are effective for every flu. Flu remains a scourge of modern civilization.”

The Spanish flu developed from regular flu symptoms of headache, chills, cough, fever, and muscle ache into a vicious illness that could kill within twenty-four hours. The most vulnerable were twenty to forty-year-olds, not children and the elderly, flu’s usual victims.

“No one knows why some flus disproportionately affect more people in some age groups than others,” Dr. Levy says. “The 1918 flu virus seemed to cause a massive immune reaction that led to respiratory distress syndrome in previously healthy people. Many of them succumbed to hemorrhagic pulmonary oedema [bloody fluid in the lungs].”

Dr. E.A. Robertson, a doctor at the Quebec City Garrison where the disease was rampant, described its terrible symptoms in the February 1919 Canadian Medical Association Journal.

“When first seen, the patient’s face was flushed, the nostrils blocked, the tongue heavily coated with thick whitish fur at the edges with a brown centre, the lips blue, the throat dark red, the skin hot and moist, the temperature 103 or 104 degrees ... As time went on, quantities of blood-stained expectoration or nearly pure dark blood was expelled, respiration became laboured, face and fingers cyanosed, active delirium came on, the tongue became dry and brown, the whole surface of the body blue and the patient died from failure of respiration.”

Unable to attend

It can be argued that the Spanish flu may have changed the course of international history. Pacifist U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was disabled by flu during the negotiations for the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I.

Had he been able to participate, the treaty would certainly have been more humanitarian and equitable. In his absence, the final form of the treaty drafted by the triumphant Allies was so punitive and restrictive for the defeated side that a decade later, an unemployed Austrian painter sought to strike back against the Allies who had imposed these rules on his people. Thus Adolf Hitler began the march to World War II.

(Excerpt from Bird Flu: What We Need to Know by A.A. Avlicino, a medical researcher and science writer living in rural Alberta. Published by Heritage House, 2006.)

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The Spanish flu is thought to have shortened World War I because so many soldiers on both sides fell ill. Soldiers returning home brought the flu with them. Since initial symptoms were mild, the soldiers were not isolated and they spread the disease as they travelled across the country.

“It was some time before authorities realized the pandemic was spreading across the country’s rail routes,” Betty O’Keefe and Ian Macdonald wrote in their 2004 book Dr. Fred and the Spanish Lady: Fighting The Killer Flu about how Vancouver’s public health officer, Dr. Fred Underhill, handled the crisis.

“The failure to restrict train travel early on was one of the terrible oversights … Eventually rail traffic was curtailed almost completely, but not before thousands of passengers and employees had taken ill.”

No part of Canada escaped the flu. It took from late September until late November for the worst of the flu to abate in Canada.

According to the November 1918 Canadian Medical Journal, Montreal, then Canada’s largest city and where most of the infected returning soldiers landed, was worst hit.

Out of Montreal’s population of 640,000, influenza and complications, chiefly pneumonia, killed 3,128. Toronto, the second-largest city at the time, followed with 1,600 deaths out of a population of 490,000.

There was misery everywhere, and no cure or preventive vaccine. Connaught Laboratories of Toronto, established in 1914, worked day and night to produce a vaccine, largely from human blood cultures obtained from the New York City Health Department.

Connaught supplied it free to provincial health departments, hospitals, the military, and health officials. The company made no claim that its vaccine would help; it did not, but it did no harm, either.

“Under the circumstances and limited knowledge of the time, the trial of Connaught’s vaccine was warranted,” says Christopher Rutty, historical consultant to Sanofi pasteur, Connaught’s current owner. “The experience helped establish Connaught as a national public health centre.”

Several measures were taken to treat the symptoms. For the accompanying acidosis (excessive acid in the body), doctors recommended alkaline medication in the form of bicarbonate of soda, citrate of potash, or limewater and milk.

Moderate doses of heroin were used for coughing and insomnia; and to clean out the digestive tract, a saline cathartic was recommended, such as Epsom salts. Aspirin had been suggested as a way of treating influenza in a 1904 American textbook, Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics, but no mention was made of it in Canadian Medical Association Journal articles on influenza of this period.

Since the outbreak of the Spanish flu, progress to find effective treatment has been slow. Even today’s flu antivirals only reduce illness duration by a day or two.

Desperate Canadians resorted to camphor, even laxatives, although doctors said they were useless. Alcohol was regarded as a form of pain relief, but there was a shortage because army demands were filled first and Prohibition was in force. The public turned to patent medicines that were laced with alcohol or narcotics.

“The 1918 flu is instructive in that it showed people can seek redress from contagion in wrong ways and quackery can run rife,” Dr. Levy says. “There is always fear of things we can’t see or control. Anxiety is natural, but irrational or unreasonable fear can be very debilitating.”

In newspaper ads, enterprising businesses promoted their products as essential to warding off the flu.

Eaton’s department store: “Keeping Warm Spells Safety First in These Days of Epidemic and Chilly Houses. Slippers That the Convalescent Will Specially Appreciate.”

Bovril (a beef extract beverage): “Guard Against Epidemics by building up the defensive forces of the body with Bovril.”

Milton’s Jaeger Pure Wool of Montreal: “Don’t Get The Flu. Let Jaeger Pure Wool Protect You From Chill. Consult us as you would your Doctor.”

Dominion of Canada Guarantee and Accident Insurance Company: “Our special sickness policy covers Spanish Influenza. Pays a weekly indemnity and makes a weekly provision for hospital expenses.” (In 1918 there were more life insurance claims in Canada related to influenza: 32.6 percent, than to the war: 20.95 percent.)

Isolation of the sick was the primary tactic taken to halt the spread of the flu, a course of action still followed today. Wrote Dr. H.O. Howitt of Guelph, Ontario, in the November 1919 Canadian Journal of Public Health:

“I know of a town in Ontario with only two doctors and a hospital well out of town. Doctor One kept his patients at home in the bed he found them in and preached the rules and lost very few patients. Doctor Two had his patients driven in an ordinary conveyance to the hospital and used many drugs but was unfortunate in his results.”

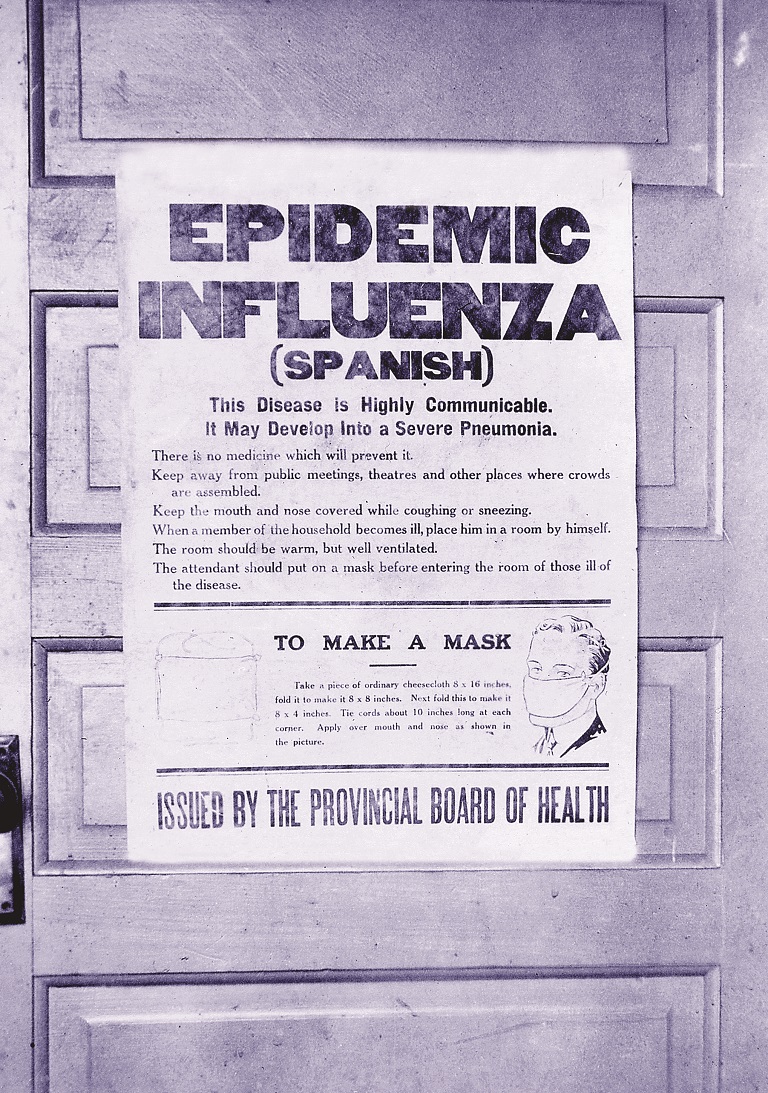

Doctors found that surgical masks (also worn during the SARS scare) were ineffective. Dr. T.H. Whitelaw, Edmonton’s medical officer of health, wrote in the December 1919 Canadian Medical Association Journal:

“The number of cases continued to increase after the Province of Alberta ordered everyone to wear a mask outside the home and public confidence in it as a prevention soon gave place to ridicule.”

Whitelaw was adamant that quarantine, used against scarlet fever and diphtheria, was impractical with the flu. Reliance on quarantine was not always effective, Dr. Whitelaw cautioned:

The number of cases reported and quarantined did not represent more than 60 percent of the actual cases. Hundreds of cases were so doubtful or mild in nature as to be regarded as common colds. Many citizens regarded quarantine placards as an injustice because their neighbours avoided quarantine by concealment or evasion. Some physicians began to be careless or indifferent in reporting because they alleged other physicians were not [reporting] … To have attempted prosecution would have been impractical because no magistrate would be likely to convict owing to the impossibility of absolute certainty in the diagnosis of most cases … The maintaining of bodily health by normal living and the avoidance of panic, worry or fatigue, seemed to be the only practical method of combating the infection.

Many communities ordered stores and bars to close early and public places such as theatres, movie houses, dancehalls, bowling alleys, auction rooms, and churches to close entirely. Schools were closed, too.

However, Dr. John McCullough, chief officer of Ontario’s Board of Health, argued in the November 1918 Canadian Medical Health Association Journal that “the utility of closing churches, schools, theatres, etc. is obviously limited when department stores, business places and street and railway cars are allowed to carry on business as usual. There seems to be no doubt that children would be better at school than running in the streets and spending their time (as they have in large numbers in Toronto) in the shops.”

Businesses urged staff to take anti-flu precautions. A September 29, 1918, memo to employees from Bell Telephone Company president L.B. McFarlane recommended covering the mouth when sneezing or coughing, gargling with salt water, and avoiding crowds.

“It is a public duty, as well as a personal advantage, that our employees should avoid the epidemic by every possible means,” he concluded.

Nevertheless, so many operators fell ill that Bell placed ads in the Montreal newspapers in October asking the public to only use the phone when “absolutely necessary" to enable the “prompt and efficient handling of important government calls and calls to physicians.”

In Montreal, the Roman Catholic Church ingeniously dealt with church closure. Sunday morning, the bourdon of Notre Dame Cathedral pealed forth, signalling parish priests to celebrate Mass on behalf of their absent congregation. Priests then brought the sacred host to parishioners’ homes themselves.

On October 22, the Montreal Gazette reported an animal-friendly corollary of the flu.

“With hunting conditions at their best just now in the northern Quebec woods, there are practically no hunters about and the game is enjoying an immunity hitherto unknown at this season of the year … the epidemic has got into the woods and many of the guides employed by the various fish and game clubs are ill.”

The flu was especially hard on medical workers. “Fatigue among doctors and nurses, who necessarily had to work long hours, undoubtedly accounted for their tending to eventually fall victims to the disease, rather than the element of special exposure which their work entailed,” Dr. Whitelaw observed.

Given time for perspective, the Canadian Medical Association’s Dr. Levy reasons, “My impression is that doctors handled the situation with professional fortitude. They were exhausted but kept working, mobilizing volunteers to help in secondary ways, and also providing support to those physicians unable to carry on.”

At that time, Canada had no federal health department to coordinate a national response, only provincial and municipal authorities. The federal department was created in 1919, largely in response to the Spanish flu.

“It’s clear that there is an important role for governments in public health,” Dr. Levy says. “They must demonstrate strong and decisive leadership to ensure that the best available resources are brought to bear on public health challenges including overwhelming emergencies. It’s good that we have an agency to help us deal with future threats.”

Nearly ninety years later, there is much to be learned from how Canada responded to the major health threat of the Spanish flu.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Have patients

At the Ontario legislature, Dr. Margaret Patterson gave three lengthy lectures on caring for patients at home, which the Toronto Globe printed in October 1918 as a valuable public service. Her advice is still useful today:

Location of “sick” room: Should be convenient to the bathroom. Not connected to any of the living rooms to keep the patient separate from other members of the household. South or southwest exposure best. A south or southwest exposure in the afternoon when the patient feels tired and depressed has an almost magical effect. No disease germ can withstand the direct rays of the sun for any length of time.

Ventilation: Convince the household they will never get a cold from fresh air … There must be pure air in the lungs if there is to be any chance for your patient. We can live three weeks without food, days without drink, but only a few minutes without oxygen and it is obtained from the air we breathe.

Nose blowing: Use crepe toilet paper, put the pieces in a paper bag and burn the bags.

Meals: Should be light. Keep patient’s dishes separate and wash separately.

Delirium: Never be afraid of a delirious patient. Never dispute with him. Always try to soothe him … A cold cloth on the head and warmth on the feet will help take his mind off what is worrying him and a gentle massage on the forehead will give relief and often put him to sleep.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has information available on the avian influenza.

Has the flu flown?

Many years after the tide of Spanish flu ebbed, human virus samples saved from the pandemic prove that it was much more closely related to avian viruses than anyone had thought, raising the possibility that it arose directly by mutation into a type that can infect humans.

The analyses of the Spanish flu virus show that its new counterpart shares many of the same types of mutations, compared to traditional avian viruses. It is suspected that these very mutations allowed the development of the incredibly virulent agent that killed well over fifty million people in 1918.

By 1959, early versions of the modern avian virus struck Scotland’s bird population. This wave soon petered out and didn’t surface again until thirty-two years later in turkeys in England.

However, the first recorded transmission from birds to humans occurred in Hong Kong in 1997, infecting eighteen people and killing six. Prompt action from the local authorities included slaughtering every chicken in the territory.

Next, a major outbreak hit Thailand and Vietnam’s poultry population in January 2004. Within weeks, the virus was present in neighboring Asian countries, including China, Indonesia, and Japan. More than forty million chickens were destroyed and the spread was contained two months later, after twenty-three people had died. By January 2005, half of the Vietnamese cities and provinces were infected and millions more poultry were sacrificed.

However, nothing matched the virus’ stunning reach in the winter of 2005–06. Within a few months, it had spread across Asia and the Indian subcontinent to the Middle East, Africa, and to virtually every country in Europe.

At that time it sat on the cusp of the avian migratory flyways that would bring it to the Americas. To date, almost a billion birds have died or been slaughtered.

The very structure of the avian flu virus dictates that, as it becomes better adapted to humanto-human transmission, its lethality declines, but in total it will kill far more people as it spreads to thousands or millions of times more humans. The Spanish flu killed over fifty million people, after infecting over one billion.

Various researchers have agreed that a pandemic could be just around the corner. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has said, “This virus has the potential to trigger the next pandemic, which, judging from history, is well overdue.”

Excerpt from Bird Flu: What We Need to Know by A.A. Avlicino.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!