Shining Lights in the Community

Education existed on the African continent long before colonization and the development of the slave trade. African societies had traditional schools where information, knowledge, and skills were shared among community members. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the mass enslavement of Africans by European colonizers removed millions of people from their homes and cultures, forcibly disrupting these early systems of learning. The displacement of persons of African descent caused by slavery resulted in a significant Black population in the British North American colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Lower Canada (now Quebec), and Upper Canada (now southern Ontario) by the mid-1800s. Many of these people had either escaped from slavery in the United States or had entered the region as part of the Black Loyalist migration during and after the American Revolution. Still others were people — and descendants of people — who had lived in bondage in the British North American colonies prior to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834. In the afterlife of slavery, Black Canadians continued to face social and institutional forms of discrimination, including in public school systems.

Early schooling in British North America developed as a result of public, private, and religious influences; but by the 1840s the colonies of British North America had created a standardized structure for their schooling in ways that reflected an increasing desire by education reformers to produce ideal citizens deemed to have the correct knowledge and moral values. As the number of publicly funded schools increased across the region that would become Canada, firmer boundaries were set in place to create ideal learning environments for pupils.

In areas with large Black populations, social, economic, and educational restrictions limited Black access to educational equality. This was formalized through legislation such as the 1850 Act for the better establishment and maintenance of Common Schools in Upper Canada, also known as the Common School Act. Implemented in the same year as the U.S. Fugitive Slave Act — a law that allowed enslavers to track down and recapture freedom seekers who had escaped from the slaveholding Southern states into the free states of the North — the Common School Act institutionalized racial and religious segregation by allowing for the creation of separate schools for Black and religious minorities in Canada West (as Upper Canada was known after 1841). The act stated that it was the duty of a school board, “on the application in writing of twelve or more resident heads of families, to authorize the establishment of one or more separate schools for Protestants, Roman Catholics, or coloured people.”

In theory, the act was meant to allow families the choice to opt in to separate schools for their children; but the reality was that local prejudice often forced segregated schools on Black families. In many communities, local sentiments dictated the creation of Black separate schools, as white parents, town council members, and school trustees sought to preserve exclusively white public schools and opposed integration. In his records highlighting first-hand testimonies of Black residents of Canada West, American abolitionist Benjamin Drew noted of the town of Chatham: “The prejudice against the African race is here very strongly marked. It had not been customary to levy school taxes on the colored people. Some three or four years since, a trustee assessed a school tax on some of the wealthier citizens of that class. They sent their children at once into the public school. As these sat down, the white children near them deserted the benches: and in a day or two, the white children were wholly withdrawn, leaving the school-house to the teacher and his colored pupils.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

This type of situation was so common that, despite his belief that persons of African descent had the right to access public schools, Egerton Ryerson, the superintendent of education in Canada West, was often confronted by white ratepayers and trustees who insisted on racial separation. In submitting a provision for the creation of separate Black schools in the legislature, Ryerson stated that, although he had tried to persuade ratepayers against practices of racial discrimination, “prejudice — especially, the prejudice of caste, however unchristian and absurd — is stronger than law itself.”

Despite these sentiments, racially segregated schools in Canada West remained uneven and dispersed. At times, when denied access to common schools, Black parents accepted separate schools for their children. In other instances, they pushed for integration by writing letters to local trustees, demanding equal access to schooling for their children. As a result, in areas like Toronto and Hamilton, racially integrated schools existed, while in Niagara, St. Catharines, Dresden, Simcoe, and Chatham, racially segregated schools thrived.

Nor was Canada West the only jurisdiction to institute legislation that led to the creation of racially separate schools. Nova Scotia created a similar structure whereby the law established free and compulsory education for primary-aged children while also permitting local sections of the Council of Public Instruction to “permit separate departments under the same or separate roofs for pupils of different sexes or different colors” — in other words, to authorize the creation of separate schools on the basis of race.

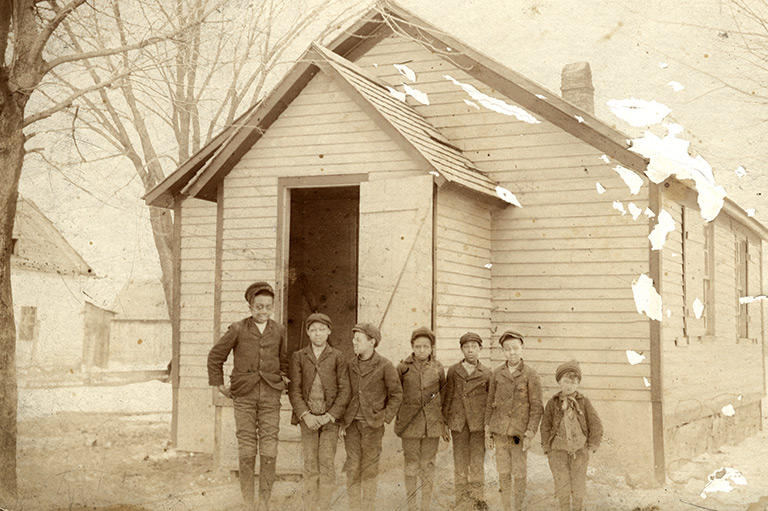

Where Black separate schools were created, they often struggled to maintain attendance, received inadequate supplies, and remained underfunded and temporary in operation. Despite these challenges, Black teachers were integral to the education of Black students at a time when Black children were often prevented from attending the common schools in their communities and were forced into a segregated system. These educators not only stood as central leaders and community activists in the realm of education, they also maintained important roles in other community institutions, including churches, social clubs, and businesses.

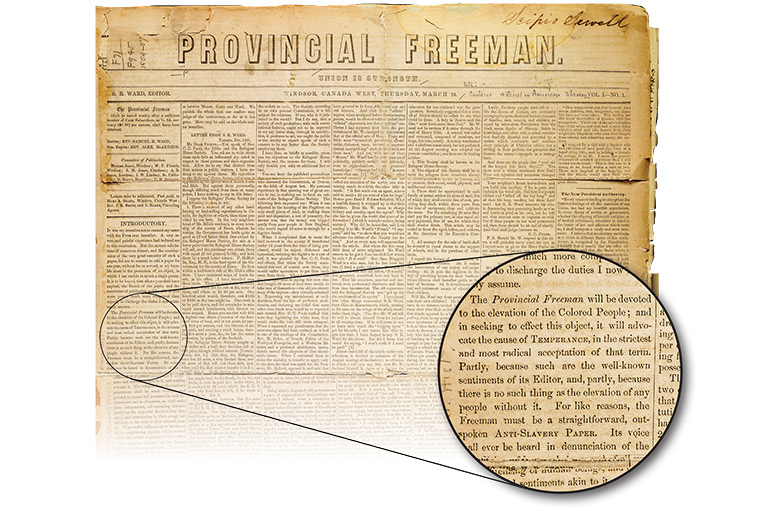

The lives of women teachers such as Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Mary Bibb testify to Black women’s long presence in the field of education. Both Shadd Cary and Bibb were Americans who immigrated to Canada West after the passage of the U.S. Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Shadd Cary is best known as an abolitionist and the editor of the Provincial Freeman newspaper, which she published from 1853 to 1857. However, after settling in Sandwich (present-day Windsor, Ontario) in 1851, Shadd Cary opened a racially integrated school and raised funds for a new building for the students. While teaching at the school, she found time for political activism and was a central figure in the local Anti-Slavery Society. Despite her best efforts, her school closed in 1853 due to underfunding.

After her school’s closure, Shadd Cary continued to use the Provincial Freeman to advocate for Black students’ access to schooling. On April 25, 1857, she cautioned her readers about the infiltration of “American books, teaching pro-slavery republican preaching negro-hating separate institutions” into schools in Canada. In a piece titled “The things most needed,” Shadd Cary wrote that what is desired “by the colored people of Canada, are a good British education, thorough instruction to the young by means of British school books by teachers British at heart — and religious instruction in the churches of the province without distinctions, and by qualified preachers, whether white or black — not as now in some cases, little places of our own, and by ignoramuses; these essentials, and a regular indoctrinating in the principles and policy of Canada Conservative politics, make up all to be desired at present.”

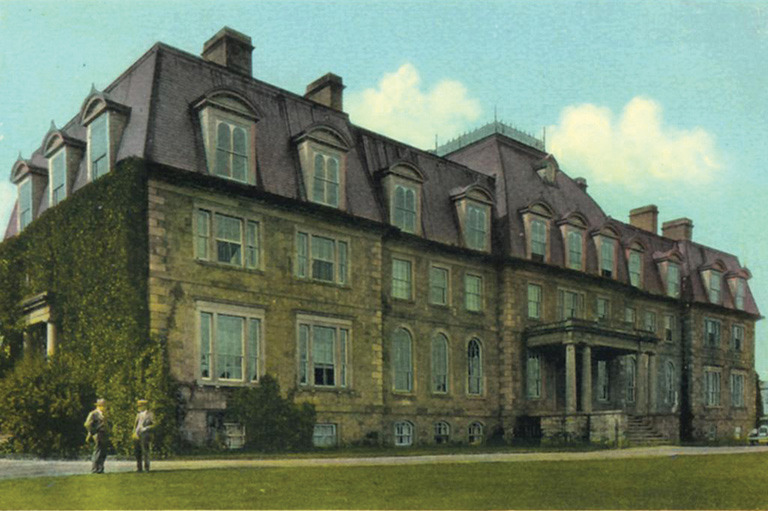

Shadd Cary and Bibb responded to the early conditions of separate schooling in Canada, but they also made the connection between Black educational access and the principles of anti-slavery, emancipation, and freedom. Although they had certain ideological differences, at the heart of Shadd Cary’s and Bibb’s pedagogies was an understanding that education was a central component of equality for persons of African descent. These women received their teacher training in the United States before settling in Canada, largely because schools for teachers, known as normal schools, were not instituted in the region until after 1847. In some cases, even after their establishment, Black teachers were restricted from attending Canadian normal schools. In the free states of the United States there was a small opening for Black educators to be trained under the auspices of religious or abolitionist institutions, missions, churches, and individuals. Oberlin College in Ohio, for example, began admitting Black students in 1835, although prior to the American Civil War such opportunities were rare.

Like Bibb and Shadd Cary, many other Black teachers were trained internationally. In New Brunswick there was no formal law that required separate education for Black children, but de facto segregation meant that all-Black schools were created to serve the Black population. Although it wasn’t illegal for white educators to teach in Black schools, there are no recorded instances of this having occurred. Sporadic in nature and chronically underfunded, Black separate schools struggled to acquire trained teachers.

For example, in 1834, a separate school was opened in Willow Grove, a Black settlement in New Brunswick that was founded by American refugees who had escaped from slavery with the help of the British Royal Navy during the War of 1812. After several petitions from Black community members, the school eventually retained a Black educator from the Caribbean by the name of Robert Lindsay Saunders. However, Saunders resigned in 1844 after receiving criticism from board inspectors and citizens of Willow Grove. In other instances, the presence of men such as Arthur Richardson highlight the complex diasporic roots of Black schoolteachers in New Brunswick.

Although no formal law prohibited them from teaching in public schools, Black teachers faced discriminatory hiring practices that limited their access to employment in the province. Mary Matilda Winslow’s career followed a trajectory similar to Richardson’s. Winslow was born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, and obtained her bachelor of arts in classics from the University of New Brunswick in 1905. Despite receiving top honours, Winslow was unable to find employment and left New Brunswick to serve as dean in the education department of the all-female Central College in Alabama. Because almost all white public schools refused to hire them, some of the most esteemed and best-trained Black educators found employment in larger Black communities in Nova Scotia, Canada West, or the United States.

At times, Black educators were able to gain employment in other racially segregated communities, a fact that highlights the complex and entrenched structures of separate education. This was the case for generations of the Alexander family, who taught in Indigenous day schools in the early twentieth century.

The ancestors of the Alexander family were formerly enslaved persons from Kentucky who settled in Anderdon Township near Amherstburg, Canada West, in the 1840s. Born in Anderdon in 1847, John H. Alexander grew up to become a teacher and principal of the King Street School in Amherstburg, where he worked for thirty years beginning in 1879. “Because of his ability, his knowledge of youth and his kindly understanding of their difficulties both in and out of school hours he was loved by all his pupils and he set them a sterling example that helped many to win success in both American and Canadian cities,” the Amherstburg Echo noted.

John H. Alexander’s daughters Mae and Ethel and his son Arthur all became teachers in their turn. In 1914, Mae and Ethel Alexander replied to an advertisement by the Six Nations School Board looking for educators. Their brother joined them two years later, after teaching for three years at the Buxton Mission School — a school founded in rural southern Ontario by abolitionist Rev. William King that provided classical education to Black children, especially those whose families had fled slavery in the United States.

All three siblings, along with Arthur’s wife, Ethel, lived in the teacher’s residence in Ohsweken, a community in the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve near Brantford, Ontario. As part of the Buxton Oral History Project in the 1970s, Arthur and Ethel Alexander were interviewed about their experiences. “I considered myself having had a pretty good living here. I’d do it over again,” Arthur said. “I had opportunities to go other places, but I couldn’t see any advantage, and so here I am yet. And I’ve enjoyed it, really.”

After leaving Six Nations, Mae moved back to Amherstburg to teach, while Ethel eventually moved to British Honduras (now Belize) to continue her educational career. Arthur’s son Arthur Alexander later went on to teach in the Buxton, Ontario, area for forty years. Given the limited opportunities for employment elsewhere in Canada, the long careers of the teachers in the Alexander family provide one example of how Black educators influenced school systems, both in Canada and abroad.

By the 1950s, the student population in Canadian schools was increasing rapidly. School administrators took several measures to address the growing teacher shortage that resulted from the country’s increasing population, including revisions to training requirements. Black educators took advantage of emergency teacher-training courses to obtain qualifications, and they benefitted from more flexible entrance requirements designed to recruit teachers from across the British Commonwealth. This led to an increasing number of Black educators, especially in schools in urban settings such as Toronto.

Although Toronto had had a significant Black population since the 1800s — largely as a result of Black Loyalist migration and African Americans escaping enslavement in the United States — no Black educator had been employed in the city’s public schools until Wilson Brooks was hired in 1952.

The shifts in training and immigration after the Second World War also offered a way for internationally trained Black teachers to enter Canadian school systems. In the 1960s, Jamaican schoolteachers were recruited to work in Alberta schools. Because their credentials were not fully recognized, these teachers often received the lowest level of accreditation in the province and had to repeat their education before they could progress. Nevertheless, internationally trained teachers from the Caribbean came with highly sought-after skills, extensive training in their home countries, and experience teaching in classrooms. Many of the Black educators who responded to the teacher shortage eventually formed the Mico Old Students Association, named after Mico University College in Kingston, Jamaica, where they had been trained. Several Jamaican educators were recruited to work in northern areas with large numbers of Indigenous students.

It was not just internationally trained educators who faced challenges to employment access and equity in Alberta; Canadian-born Black educators also found that their experiences within school systems were marked by de facto forms of social and institutional segregation. When Gwendolyn Hooks began her teaching career in 1942, she experienced anti-Black racism within schools, including discriminatory textbooks and blackface minstrel show performances.

Not only did the post-Second World War era shift the makeup of Canadian classrooms, the period also saw changing public ideas around equal rights and fundamental freedoms for all human beings. In 1948 Canada signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and by the 1950s almost all provinces had enacted policies barring discrimination in employment, housing, and the use of public facilities. Ontario passed the Fair Employment Practices Act in 1951; Nova Scotia adopted fair employment legislation in 1953; and New Brunswick instituted similar legislation in 1959. All of this happened amid the growing publicity and mobilization of the civil rights movement in the United States, targeting the desegregation of Southern schools and public facilities. In 1954, Nova Scotia removed references to “different races” from its Education Act, thereby legally removing the language of racially segregated schools — although separate schools for Black children continued to exist in the province until 1983, when the last one closed in Lincolnville. In Ontario, Liberal MPP Leonard Braithwaite, Canada’s first Black provincial legislator, advocated for the removal of the racial language in the Common School Act, leading to the closure of Ontario’s last segregated school in 1964. By the end of the 1960s, the legal framework justifying segregated schools for Black children was no more.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Black schoolteachers created new approaches to education by teaching Black history, curbing institutional discrimination, and promoting Black achievement. In the twentieth century, Toronto educators like Marlene Green helped to create and support programs such as the Black Education Project and the West Indian Social and Educational Research project.

To say that Black schoolteachers have had a lasting impact on school systems and curricula in Canada is an understatement. Their complex and long-standing presence within Canadian school systems reveals intertwined stories of professionalism, accreditation, and segregated labour and educational settings, as well as social-justice activism and advocacy. Despite facing a series of discriminatory processes at all levels of education, Black schoolteachers persevered to acquire their teaching credentials and pursued their mission to educate not only Black students but other children in their communities. On many occasions, they fought against school segregation and underfunding, particularly in provinces like Ontario and Nova Scotia, where segregated schools were authorized by law. In other instances, they used their experiences as persons of African descent to create inclusive places of learning for Black children. Ultimately, Black schoolteachers envisioned a school system where all students and teachers would be treated equally, regardless of race, and where all values and perspectives would be respected and included.

Mary Bibb

Mary Bibb opened her first school for Black children in her home in 1851. Mary and her husband, Henry Bibb, founded the Voice of the Fugitive newspaper that year to highlight the challenges and successes of Black communities in Canada West, to encourage immigration to the area, and to garner support for the anti-slavery movement in Canada and the United States. Mary Bibb was trained at the Massachusetts State Normal School and taught at several Black schools in the northern United States before her immigration to Canada. Dalhousie University professor Afua Cooper notes that, as an experienced teacher, Bibb made multiple attempts to provide educational opportunities for Black students.

An article published in the Voice of the Fugitive on January 1, 1851, observed: “In the township of Windsor, we have no school, but there is great need of one. Seven miles [eleven kilometres] above Windsor, there is quite a settlement of colored people who need a school, but have none. In Sandwich township we have great need of a school. Mrs. M.E. Bibb has commenced with 25 pupils at her residence, with the hope that some more suitable place will be provided, and means for carrying on the school properly. Nearly double this number of children would be glad to attend this school, but for want of the necessary provisions they cannot attend.”

Although Bibb’s first school closed due to limited financial support, she opened another private school in 1855 and was teaching at yet another in 1861. On his tour of Black communities in Canada West in 1861, American abolitionist William Wells Brown wrote of the “beautiful and accomplished” Mary Bibb: “Her labors during the lifetime of Mr. Bibb, in connection with him, for the fugitives, and her exertions since, are too well known for me to mention of them here. [She] has a private school with about 40 pupils, mostly children of the better class of Windsor.”

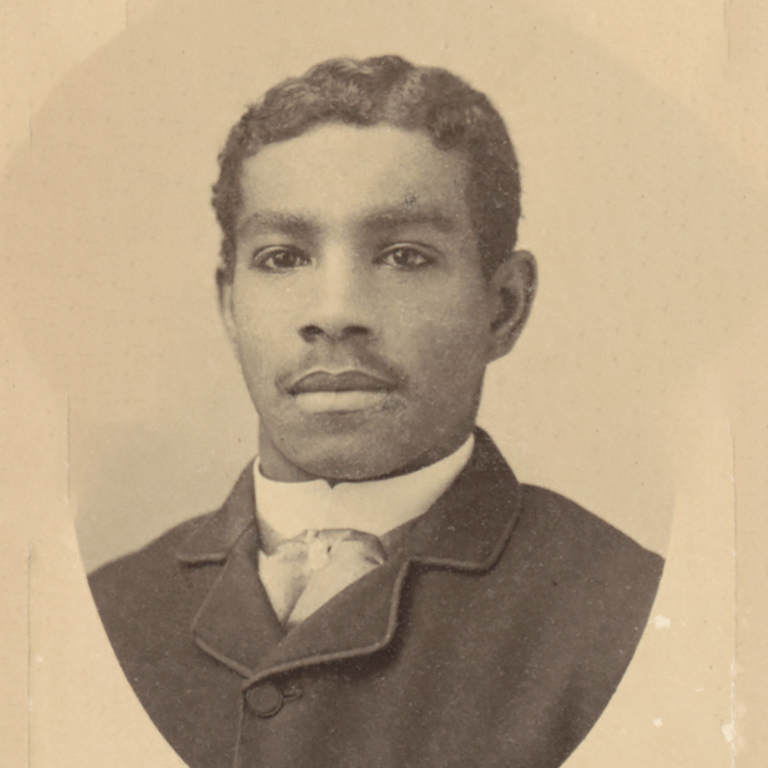

Arthur Richardson

Born in Bermuda, Arthur Richardson is recorded as the first Black man to attend the University of New Brunswick. He graduated with honours with a degree in classics in 1886. Unable to gain employment in the province, Richardson eventually worked as a teacher and principal at Wilberforce Educational Institute in Chatham, Ontario, and later taught at Morris Brown College in Atlanta. Of Black educators, he wrote: “The majority of the Negro teachers are Christian men and women of high moral character, and as such are shining lights in the community in which they may be engaged in teaching. The good they thus do is not confined to the school or classroom, but permeates every sphere of society, ennobling and enriching the thoughts and minds of all with whom they may have dealings, both by their chaste conversation and by their upright and godly lives.” Richardson’s uncle Thomas Richardson was also an educator and taught in Saint John, New Brunswick.

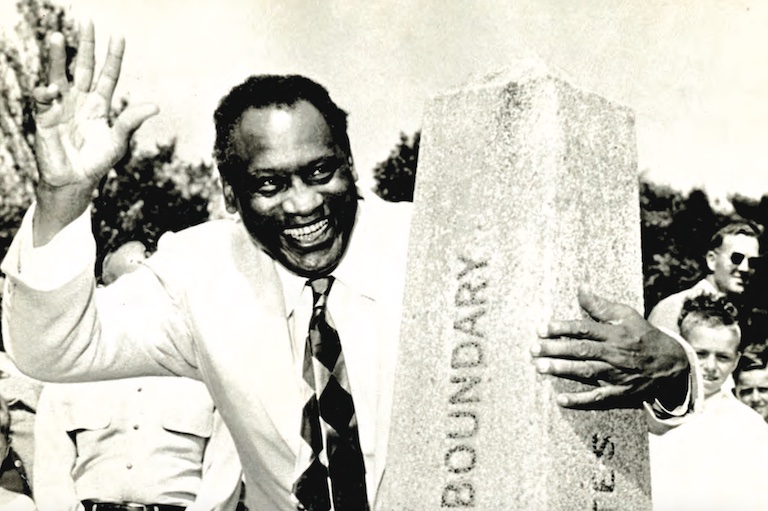

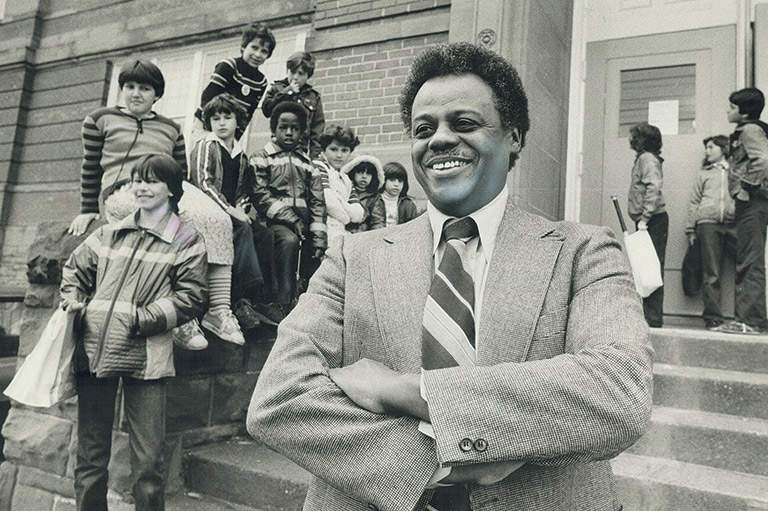

Wilson Brooks

Born in Windsor, Ontario, in 1924, Wilson Brooks served in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War. When he was hired by the Toronto Board of Education, he had already taught in Bermuda and was an active member of Toronto’s Black Canadian community. In the September 25, 1952, issue of Jet magazine, Brooks noted: “On the opening day, the first thing my pupils noticed about me was my colour. Now they know me as a teacher and a person. I think the first impression has disappeared. They can see that the colour of a person’s skin is not important.”

In 1978, he co-founded the Ontario Black History Society, which still exists today. Educators like Brooks had long-standing ties with Black-Canadian communities and used these community networks to create spaces of learning for Canada’s increasingly diverse classrooms. They considered pedagogical approaches that would open spaces of learning for all children, but especially for Black Canadians.

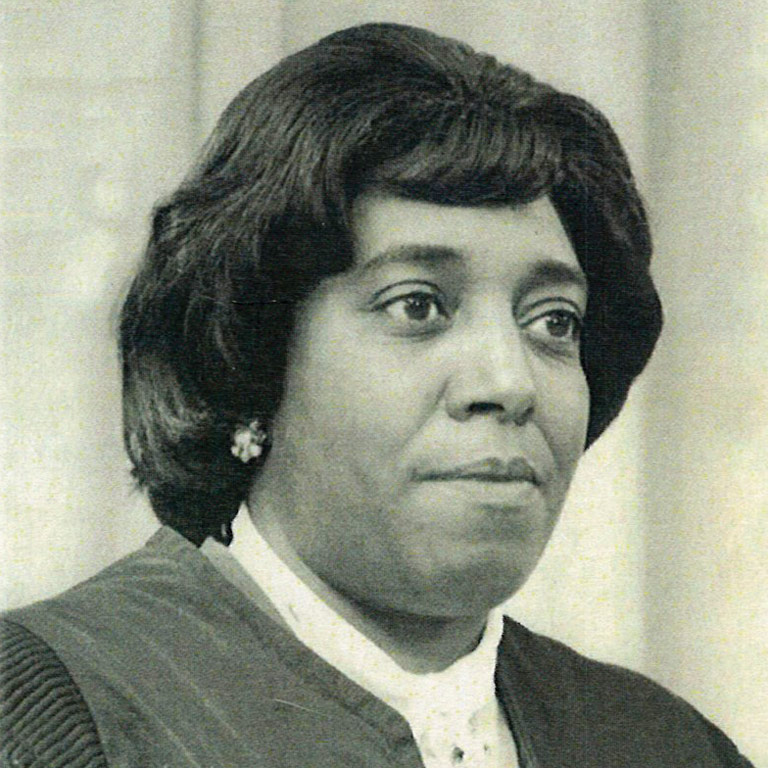

Gwendolyn Hooks

Gwendolyn Hooks’ parents moved to Alberta from Oklahoma as part of the earliest migration of Black settlers to the province between 1908 and 1911. In an interview with the Alberta Labour Institute in 2001, Hooks discussed her teaching successes while working in a variety of schools in the province. “When I came back to Breton and I was teaching at Funnel [School], and most of the children there were older. Some of them were grade nine and ten. They were big boys, so it was a ‘hard to manage’ school, hard to rule. So they gave you a bonus of one hundred dollars a year, which wasn’t that much, but one hundred dollars a year if you taught at one of those schools that were hard to manage,” Hooks explained. “In this school there was about six Black students. So we taught [and] we used to play games and we’d go out in the wintertime and go sliding. I was right with the kids.”

Hooks retired after thirty-five years of teaching and in 1997 published The Keystone Legacy: Reflections of a Black Settler, highlighting the experiences of Black pioneer families in Alberta.

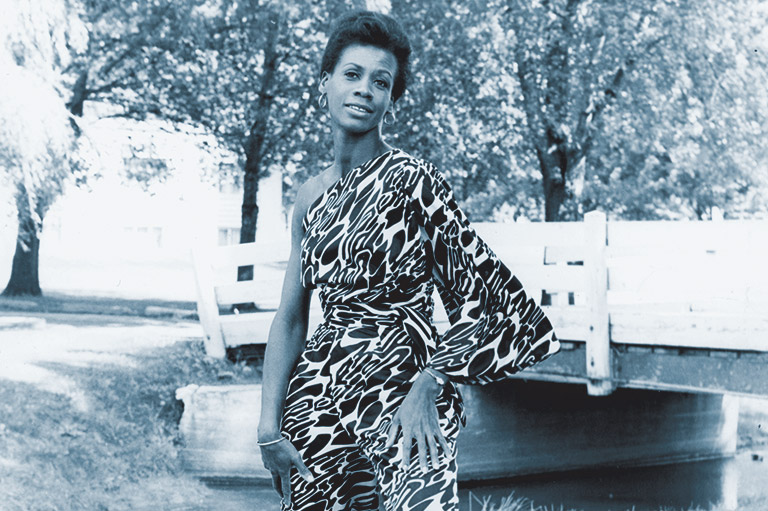

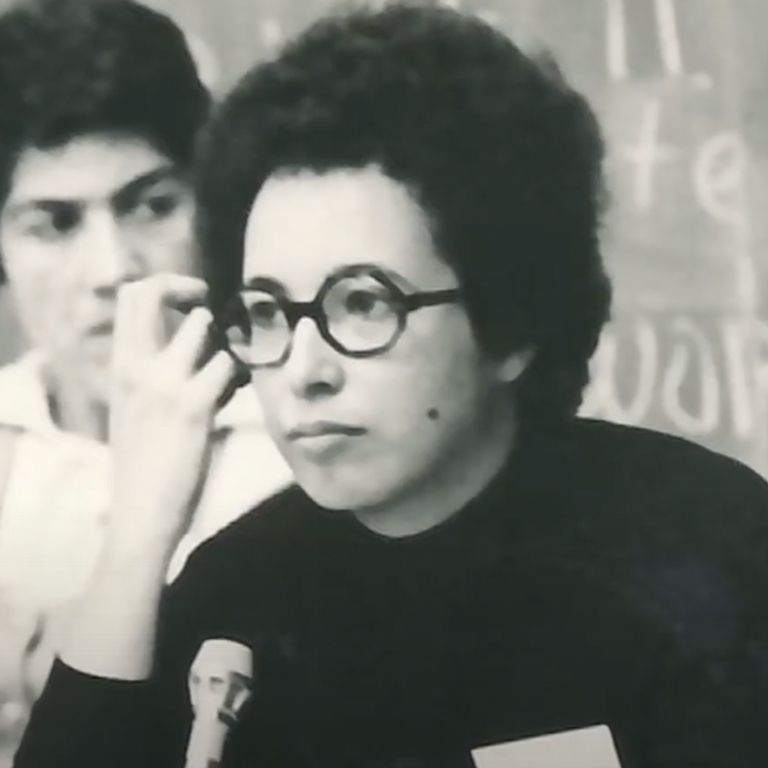

Marlene Green

In 1969, activist and educator Marlene Green founded the Black Education Project (B.E.P.), an after-hours tutoring program to “take the responsibility of giving Brothers and Sisters a chance to develop the skills necessary for survival and for building a strong black community.” The B.E.P. advocated for Black students and their parents in the Toronto school system and took a holistic approach by supporting cultural and recreational programs as well as community activism.

The program emphasized pan-Africanist thinking and support for anti-colonial struggles across the Caribbean, but also mobilized to address social concerns both inside and outside of school settings, including the treatment and mistreatment of young Black people at the hands of police. Green went on to serve as a community-relations officer for the Toronto Board of Education, bridging the gap between community and school, and she co-wrote the board’s first report on Black student experiences. Through her work with the B.E.P. , Green demonstrated the significance of Black educators in sustaining Black communities and in combatting various forms of discrimination, both inside and outside of school settings.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!