Shear Style

In my 2019 book Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture, I argue that Canada’s Black beauty culture industry has been, and continues to be, mostly a proxy for American products, services, and beauty imagery. Today, however, things are changing.

There are Black-owned beauty supply stores that offer an inventory of hair weaves and styling products. There are also hairstylists like Toronto-based Janet Jackson, an internationally known celebrity beauty expert who, in 2021, appeared alongside me and six other Black Canadian women in the #MyHairMyStory digital campaign for a product line for Afro-textured hair created by Black scientists, stylists, and dermatologists. These changes would have been unimaginable in 1962, when Kemeel Azan opened his first salon, Azan’s Beauty World, on Spadina Avenue in downtown Toronto.

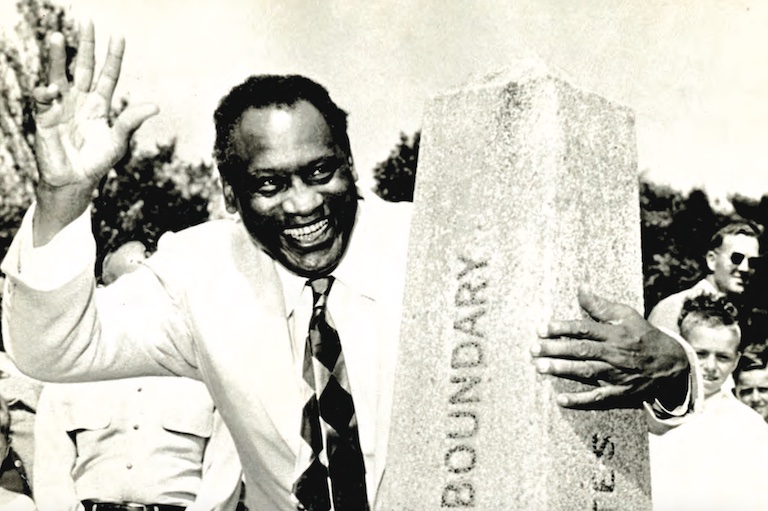

Azan, who was born in Jamaica, was drawn to Black women’s hair care when he came to Canada in the 1950s and noticed that many Black Caribbean women who worked as domestics had very few hair care options. At one point Azan had four salons, but eventually Beauty World was consolidated into one location on Davenport Road, which is still in business today, with a clientele that includes actress and filmmaker Tonya Lee Williams (a client since she was nine years old) and Toronto Centre MP and former journalist Marci Ien.

By 1970 there were twelve Black hair salons, including Azan’s, that stretched across Toronto. Before this, Black hairstylists had operated in what’s known as a kitchen and hideaway industry, where Black women did each other’s hair in non-commercial spaces, such as over their kitchen sinks, or in salons operated out of women’s apartments or basements. Today, kitchen and hideaway hair care still exists across Canada, especially in smaller cities and towns where Black hairstylists rely on word-of-mouth promotion.

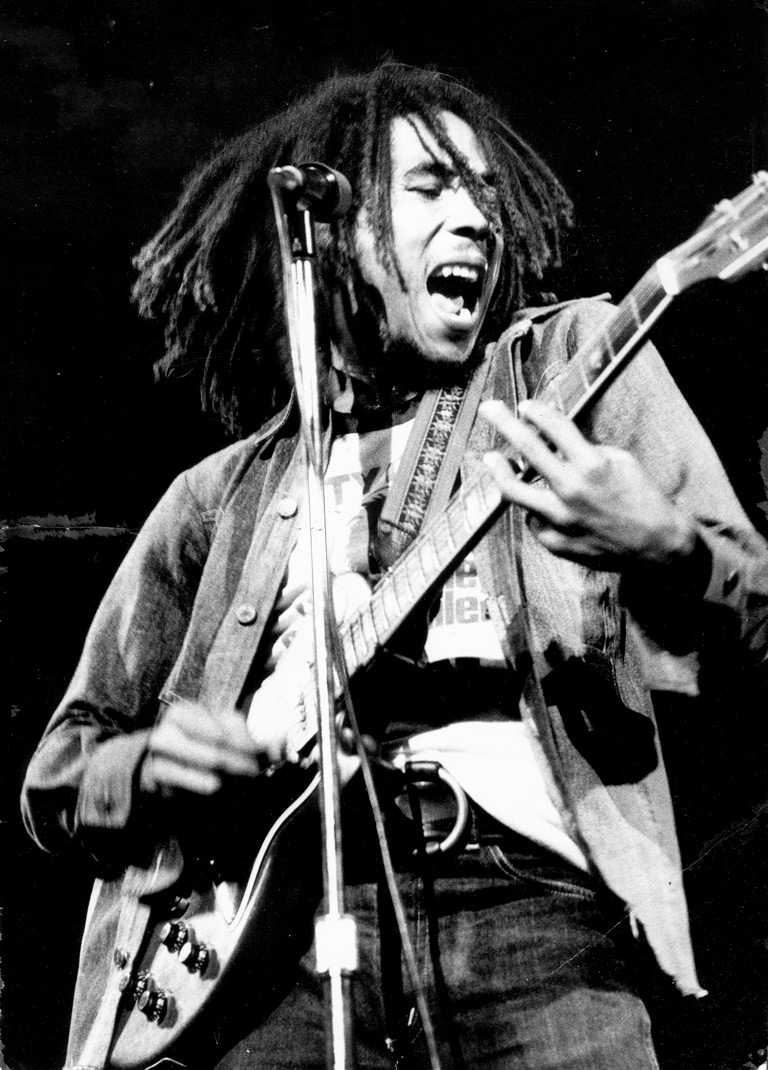

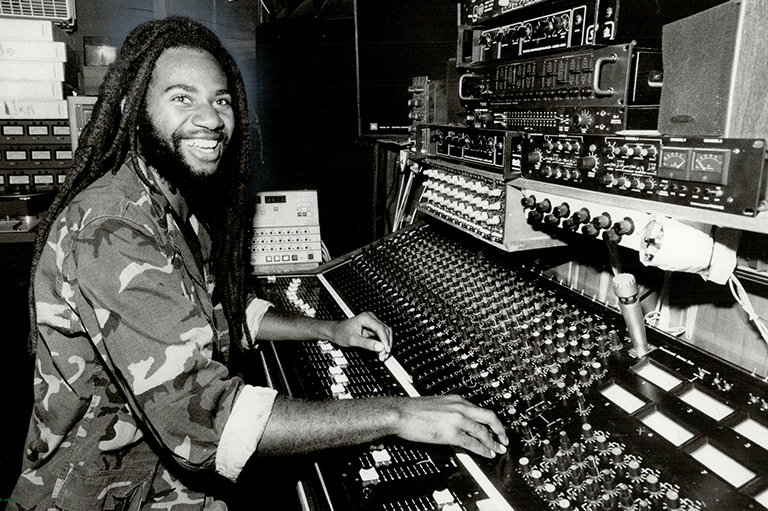

The story of Black hairstyling is intimately tied to four definitive moments. First, Madam C.J. Walker, an African-American hair mogul, developed a shampoo, press, and curl method of hair care in the 1910s that was replicated by many, including African-Nova Scotian Viola Desmond. Second, African-American celebrities popularized the pageboy hairstyle and its numerous variations in the 1940s and 1950s. Third, the 1960s civil rights era made a liberatory call for Black people to embrace their natural hair. Finally, Caribbean culture in the 1970s helped dreadlocks enter the mainstream, while product shops in the 1980s and 1990s popularized chemical straightening and hair weaving.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Born Sarah Breedlove in Louisiana in 1867, Madam C.J. Walker was the first woman in America to become a self-made millionaire, according to the Guinness Book of World Records. In the 1910s, she incorporated the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company to produce her skin and hair products, and she opened the Madam C.J. Walker School of Beauty Culture to teach others her hair care techniques. Both of these were headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana. Her product line included a hair grower, a glossine (a type of pomade), a vegetable shampoo, a tetter salve (an anti-dandruff treatment), and a temple salve (for the relief of tension headaches). Her “Walker system” of hair care included the use of products and a shampoo, press, and curl method of straightening hair, which involved the use of light oil and a wide-toothed steel comb heated on a stove to straighten the hair. African-American Annie Turnbo Malone preceded Walker in developing a product for Afrotextured hair, which she called “Wonderful Hair Grower,” in the 1900s. Walker modified Malone’s techniques and selling strategy — which involved a door-to-door pyramid-type method likely borrowed from the California Perfume Company (later known as Avon) — to grow her business.

In Halifax, a teenaged Viola Desmond read about Walker’s success and was inspired to follow in her footsteps. She studied at the Madam C.J. Walker Beauty School, earned a diploma from another trailblazing African-American entrepreneur, Madam Sara Spencer Washington, at her Apex College of Beauty Culture and Hairdressing in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and further trained in New York. This education allowed Desmond to operate her own beauty salon, Vi’s Studio of Beauty Culture, on Gottingen Street in the North End of Halifax’s downtown. Like her African-American counterparts, Desmond specialized in selling hair care products and performing press and curls, and she also sold chignons, hairpieces, and wigs. The popularity of the press and curl, also referred to as thermal straightening because of the use of a hot comb, was largely a result of the socio-cultural conditions under Jim Crow segregation that made Black women (and men) feel that they needed to appear neat and proper in public to avoid undue attention from whites.

Eventually, Desmond opened the Desmond School of Beauty Culture, where she taught Black women from across Canada the techniques of hair straightening — until the events of 1946, when she refused to give up her seat in the whites-only section of the Roseland movie theatre in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. She was arrested, jailed overnight, convicted of an obscure tax offence based on the cost of her movie ticket, and fined — an experience that led to her shutting down her businesses.

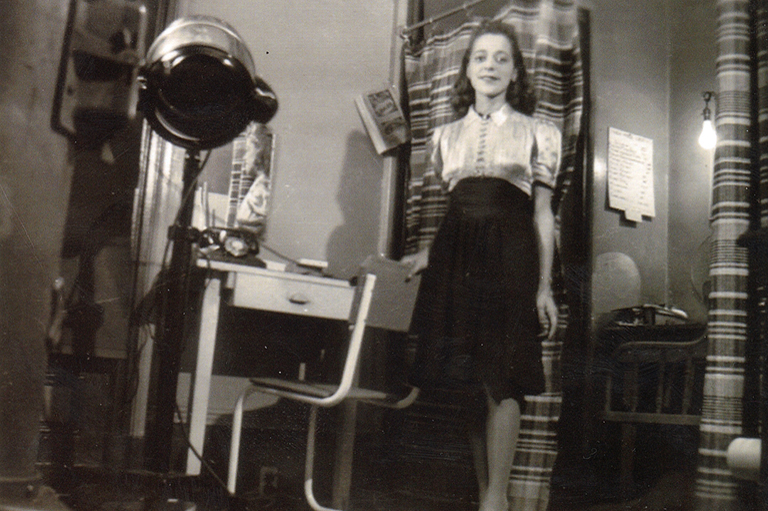

Following her ordeal, when Desmond appeared on the front page of the December 1946 issue of the Clarion — the African-Nova Scotian newspaper founded in New Glasgow by journalist and civil rights activist Carrie M. Best — she wore her hair in a pageboy style. This style, which involved straightening the hair with the use of a hot comb and then curling it under at the ends with bangs at the front, was most popular among middle-class Black women during the 1940s and 1950s. The hairstyle was inspired by the onscreen success of Hollywood stars Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne, both of whom increased their public profile by appearing in stories in African-American magazines like Ebony and Jet. Variations on the pageboy hairstyle included cluster curls, in which the hair was curled in the front, and chignons, in which the hair was pinned into a knot at the back of the head. Feather curls, which involved layering the hair, were also popular during this period. As women desired these glamorous hairstyles, the market for hair attachments, then known as falsies, took off.

The politics of respectability during the Jim Crow era of segregation meant that the Black hair care industry often took its cues from the dominant culture’s standards of beauty. The race politics of the 1940s ultimately motivated many Black women to wear straightened hairstyles like the pageboy. Thus, in the 1950s, Black women continued to wear the pageboy and its variations, but some began to wear their hair short in a pixie or bob, styles popularized by actresses Leslie Caron and Audrey Hepburn, because those styles also came to be viewed as beautiful. Black women continued to take their beauty cues from the dominant culture. However, during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Black hairstyling profoundly changed.

Between 1964 and 1966, a new African-identified aesthetic, known as the Afro, became the hairstyle of choice for Black people around the world. The rise in the United States of the Black Panther Party, a Black political organization founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, and the philosophy of other activists such as the Trinidadian-born Stokely Carmichael, influenced a whole generation of Black people to reclaim African aesthetics as part of their demand for civil rights. This movement became known as “Black is Beautiful.”

In the television drama series East Side, West Side, which aired in the United States on CBS from 1963 to 1964, actor Cicely Tyson helped to spearhead the movement when she wore a short, cropped Afro in her role as Jane Foster, the secretary in a social welfare office in New York City. Afros of different shapes and sizes were given names. The petite was a small, round Afro; the ebonette was slightly larger and more oval in shape; the princess was a large, round Afro; the first lady was a medium-sized, round Afro; the elegante was a short-cut Afro; and the Afrique was a coiffed Afro that was curved and elongated at the front.

Tyson also wore cornrows, a traditional African hairstyle created by tightly braiding hair into rows. Cornrows had also been worn by enslaved persons in the United States and the Caribbean, where elaborate hairstyles replicated the plantation grounds, acting as a guide to help people escape. Following the emancipation of enslaved African-Americans at the end of the U.S. Civil War, the hairstyle was deemed backwards — a reminder of a past of enslavement. As such it went out of style until Tyson brought it back into the mainstream as a fashionable hairdo. When African-American singers like James Brown, who sang the 1968 hit “Say it Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud,” adopted the Afro, they also helped to popularize the hairstyle. By the end of the 1970s, however, with the emergence of multiple chemical hair-straightening products and the rise of dreadlocks, a natural aesthetic associated with Jamaicans, the Afro craze came to an end.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

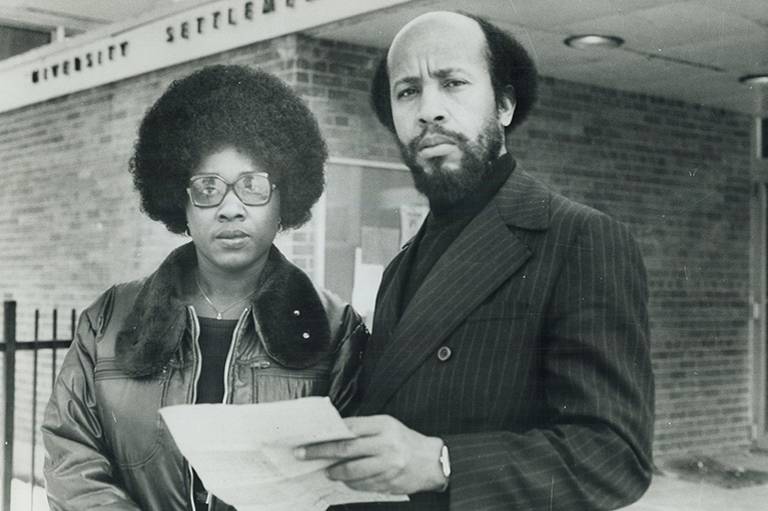

In 1970, Nova Scotia-born Beverly Mascoll founded Mascoll Beauty Supply Ltd. in Toronto’s Bathurst and Bloor neighbourhood — an area euphemistically known as “Blackhurst” due to the numerous Black-owned businesses that lined Bathurst Street in the 1970s. Mascoll’s Beauty Supply revolutionized the sale of Black beauty products in Canada. As a teenager in the 1990s, I frequently shopped there and marvelled at the store’s shelves that were lined with shampoos, conditioners, wigs, and wiglets, as well as chemical hair straighteners, known as relaxers because they relax tightly coiled hair.

Since the nineteenth century, Black entrepreneurs had experimented with chemical concoctions for their hair. African-American Garrett Augustus Morgan invented a relaxer in 1909, but the first person to commercialize a chemical relaxer was Mexican-born José Baraquiel Calva. He invented a product called Lustrasilk and offered it for sale at licensed hair salons in 1948. In the late 1950s, George E. Johnson’s Ultra Wave became the first relaxer that could be applied at home. By the 1980s, chemical relaxers usurped the shampoo, press, and curl — which until then had still been popular in hair salons — as the dominant method of hair straightening. In the 1980s, the emergent fashion and beauty magazine culture made straightened hair the dominant aesthetic. From coast to coast, Black Canadians achieved success as distributors and retailers of these chemical products. Toronto had Mascoll’s. In Calgary, Maurice and Ann Walters owned and operated the Plaza Drug Store (the first Black-owned drugstore in Western Canada). Mainstream drugstores also began to sell Black beauty products.

In the 1980s, Black hairstyles ranged from chemically straightened blowouts to the Jheri curl, worn by singer Michael Jackson on the cover of his chart-topping 1982 album Thriller. This style required a chemical process to start, followed by the daily, abundant use of curl-activator sprays, oils, and moisturizers to achieve ringlet-like curls. As the Black beauty product industry grew exponentially because of chemical hair-straightening products, dreadlocks also became more popular for those who sought a natural alternative. Before reggae artist Bob Marley appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1976, most people outside of Jamaica had never seen dreadlocks. By the 1990s, dreadlocks were frequently referred to as locs, as more Black professionals adopted the hairstyle. For some people locs carried the same socio-political meaning as the 1960s Afro, but for many, the hairstyle was part of a healthy lifestyle that included a move away from harsh chemicals and hot combs. In Toronto, hairstylists specializing in the care and treatment of locs, known as locticians, sprouted up across the city. One of them was Strictly Roots, where I started my locs in 2007 before the owner, Ruth Smith, relocated the business to Ghana.

Throughout the 1990s, hair weaves, which involve adding synthetic or real hair to one’s own hair, became an alternative hairstyle to relaxers and locs. Besides being alternatives to chemical straightening, weaves serve as a protective cover for natural hair, allowing women to wear straighthaired dos like feather curls and chignons without using a relaxer. Another popular type of weave is a lace-front wig. This type of wig can be worn over short hair or over long hair braided into cornrows. The wig is either sewn on to the braided hair beneath it, or fastened to a cap that is glued with an adhesive to the scalp.

Today, Black hairstyling is whatever people want it to be — natural or straightened, twisted or cornrowed. From Vancouver to Halifax, brick-and-mortar shops and kitchen and hideaway businesses are keeping Black hair traditions alive. What’s needed, however, is institutional support from cosmetology schools — where, in 2022, there remains no mandatory Black hair training for stylists — and from provincial licensing bodies, whose exams include very little about textured hair.

The history of Black hair reveals centuries of diverse hairstyles. However, there remains a lack of knowledge about it among the general population in Canada. My hope for the future is that Black hair will become widely accepted and appreciated for its varied lengths and textures — because Black hair is beautiful.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!