Made in Canada: Games We Play

Basketball

Given just fourteen days to invent a new indoor game as an athletic distraction for rowdy students during cold winters, Dr. James Naismith succeeded far beyond what he and his school could have hoped for.

Born in Almonte, Ontario, Naismith attended McGill University in Montreal and was working as a physical education instructor at the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts, when he invented basketball in 1891. His new game used two peach baskets affixed to ten-foot-high railings and was played with a soccer ball and nine players on each team.

The game involved thirteen rules, with the side making the most goals by throwing or batting the ball into the baskets being declared the winner. Eventually, baskets were used with the bottom ends removed to allow the ball to fall through them.

The first official game took place on January 20, 1892. One of Naismith’s students called it “basket ball,” and the name stuck.

Naismith’s dedication to developing character through sport paid off — the game became part of the school curriculum in Canada and around the world.

— Beverley Tallon

Advertisement

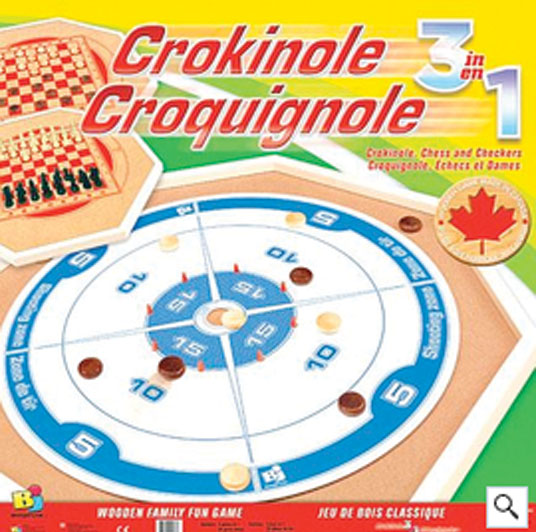

Crokinole

It may have sister versions around the world, but the game of crokinole as we know it today was likely born in southwestern Ontario. The earliest known crokinole board was created in 1876 in Sebastopol, Ontario, by Eckhardt Wettlaufer as a birthday gift for his five-year-old son Adam.

Wettlaufer was well-known for his woodworking skills, including decorative work on sleighs and wagons. He also earned a patent for a cider press.

Other crokinole boards from this time period have been found in the same part of Ontario, though the game was patented in New York in 1880.

Crokinole is played on round or octagonal boards by two players or teams. Players flick disks across the board, attempting to knock off their opponent’s disks and to place theirs as close as possible to the board’s centre. The octagonal design was intended to prevent boards from rolling when propped against a wall for storage.

The word “crokinole” is derived from the French croquignole, which describes the action of flicking with a finger. Similar versions of the game, including British shovelboard and East Indian carrom, are considered precursors.

The World Crokinole Championship is held each year in Tavistock, Ontario, near Sebastopol.

— Sandy Klowak

Five-pin bowling

Thomas F. “Tommy” Ryan opened Canada’s first regulation 10-pin bowling alley in 1905 on the second floor of the Boisseau Building in Toronto. Ryan’s elite and private club was graced by a piano, a string orchestra and lush, tropical plants. The customers, apparently in need of some strength training, began complaining about the size and weight of the 10-pin balls.

Ryan asked his father to reduce the size of the pins to about three-quarters of the originals. He spaced five of them equally apart on the 10-pin triangle, using a small rubber ball to knock them down. The new game required a new scoring system, which Ryan devised.

For his “strike” of genius, Thomas Ryan was inducted into the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame in 1971.

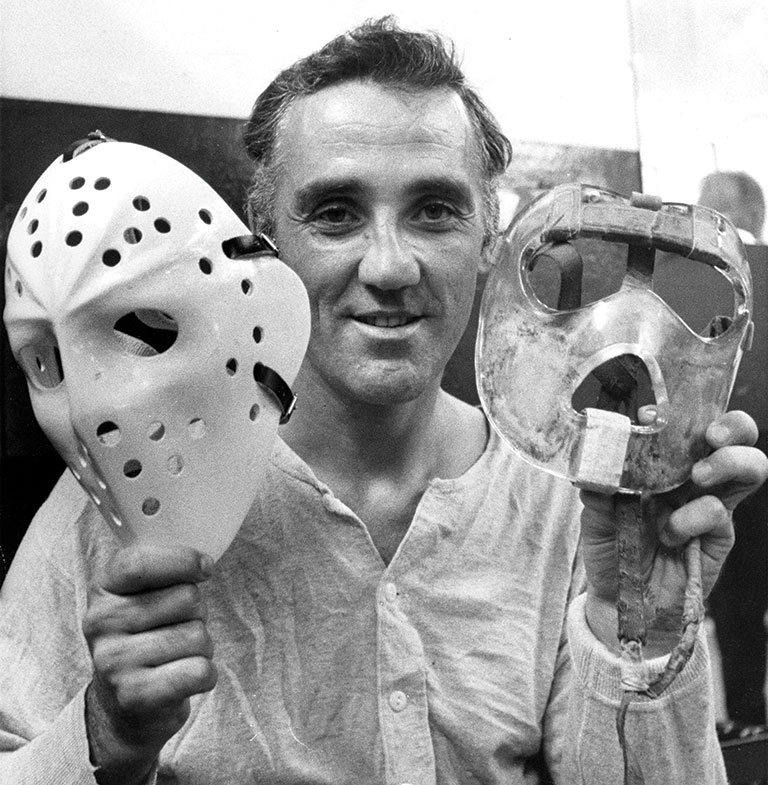

Goalie Mask

The story of NHL goaltender Jacques Plante having his face split open by a puck and returning to the game wearing a protective mask is legendary, but Bill Burchmore, the man behind the piece of fibreglass that revolutionized hockey, is less recognized.

Burchmore, who worked for Fiberglass Canada, watched Plante make a save with his forehead in 1958, and the image of a dazed, bleeding Plante remained with him the next day. Staring at a mannequin head, he was inspired to experiment with fibreglass cloth and polyester resin.

Plante had worn other masks in practice and initially resisted Burchmore’s idea, but agreed to try it at the urging of the Montreal Canadiens’ medical staff. During the summer of 1959, Burchmore made a plaster mould of Plante’s face. He then layered sheets of resin-soaked fibreglass cloth on the mould. The result was lightweight, virtually unbreakable, and only three millimetres thick.

Plante first wore the mask in an NHL game on November 1, 1959. Throughout the 1960s, as more goalies followed his lead, the mask changed the way the game was played. Goalies no longer had to remain upright and could drop to the ice without fear of facial injury.

— Neil Babaluk

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

IMAX

The large motion picture format shown in theatres around the world had its beginnings in Canada’s National Film Board and in the creative energies showcased at Montreal’s Expo 67.

Graeme Ferguson and Roman Kroitor had both been interns at the NFB, and Kroitor was employed there when he proposed a multi-screen experimental film for the Expo. Ferguson, meanwhile, worked as an independent filmmaker and was asked to make his own film for Expo 67. He approached his former Galt, Ontario, schoolmate Robert Kerr to set up a production company.

At Expo 67, experimental film projections using many screens and projectors in different arrangements were a huge success, and the Fuji company asked Kroitor to participate in Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan. He and Ferguson discussed the possibility of using a single projector to improve image quality and reduce complications. With Kerr they formed the Multiscreen Corporation, which soon changed its name to IMAX.

Extending techniques developed in Norway and Australia, and with help from another former Galt schoolmate, Bill Shaw, the company developed a large-format projector and camera in time to show the film Tiger Child in Osaka.

The following year, the first permanent IMAX theatre opened at Ontario Place in Toronto.

— Phil Koch

Advertisement

Instant Replay

We didn’t catch that — play it again … and again … give us an “instant replay!”

A technology that most sports fans now take for granted, instant replay was first invented in the mid-1950s by George Retzlaff, who worked at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation when television was in its infancy and full of experimentation. In 1953, the Germanborn Winnipegger was promoted to head of CBC Sports and producer/director of Hockey Night in Canada.

During the 1955–56 NHL season, Retzlaff used a “hot processor” that could develop film footage within thirty seconds, allowing almost instant replays. But he was only able to use his new technique for one Toronto-based Telecast.

The new method did not conform to a network requirement that hockey programs had to look the same whether telecast from Toronto or Montreal. As well, the network’s advertising agency was annoyed that Retzlaff had failed to provide advance notice so that it could promote the innovation.

With the advent of videotape in the mid-1960s, instant replay became commonplace, allowing both television viewers and sports officials to see different angles and review plays and rulings. Almost every sport that is televised today uses some form of George Retzlaff’s instant replay.

— Beverley Tallon

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

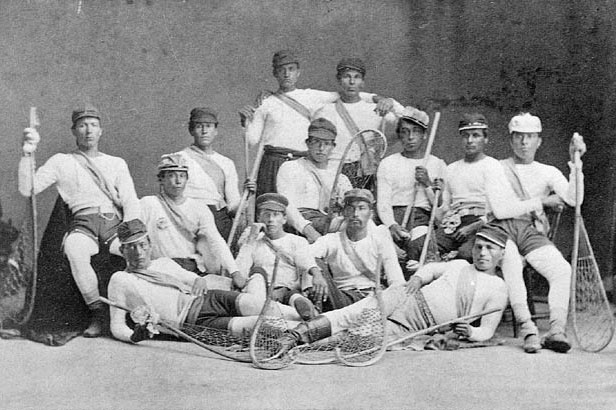

Lacrosse

Fast-paced, requiring quick reflexes and skill at ball handling and passing, lacrosse likely originated in the 1300s or 1400s among the Huron, Algonquian, and Iroquois. Despite popularity among First Nations as far south as Mexico, only Canada, in 1859, made lacrosse an official sport. Parliament reaffirmed it as our official summer sport in 1994.

Early lacrosse games — called baggataway (“they bump hips,” Algonquian) or Tewaarathon (“little brother of war,” Iroquois) — would last from sunup to sundown, sometimes for several days. Part religious ritual, part military training, and part inter-tribal negotiation, games took place in the open. Goals might be half a mile apart, and teams could have hundreds of players. Sticks were three to four feet long, tipped with small nets for catching and holding a hair-stuffed deerskin ball or a stone.

French Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf called the game “la crosse” because the sticks resembled the crozier, or crosse, carried by bishops. By the 1840s, French and other settlers were playing the game, adding rules for fewer players, shorter sticks, and smaller fields. Lacrosse blended European and First Nations cultures — though it would be a while before any settlers team could best a First Nations team.

— Danielle Conolly

Table Hockey

When Canadians gather around the kitchen table this winter for a rousing game of table hockey, amid the shouts of “He shoots, he scores!” they might give a tip of the hat to Toronto’s Donald H. Munro. Donald who?

Whatever on-ice team you cheer for, you can thank Munro for making the first mechanical hockey game. He fashioned it out of found wood and scrap metal as a Christmas present for his children during the Great Depression, but soon began selling games through the T. Eaton Company.

The Munro Standard Model, listed at $4.95 in Eaton’s 1939–40 catalogue, resembled a two-sided pinball game with pivoting wooden pegs and wire loops to shoot the “puck” — which was in fact a metal ball.

Munro had a number of competitors, including Montreal’s Eagle Toy Company, which in 1954 introduced a model with moving rods and painted, cutout players that could pivot 360 degrees.

Munro and Eagle produced competing designs that gained in popularity after NHL games were televised in the 1950s and when the league expanded in 1967. With hundreds of thousands of table hockey games being purchased each year, both businesses were sold to U.S. companies in 1968.

Table hockey has enjoyed continuing but limited popularity since the advent of video games.

— Kristen Fry

Advertisement

Toboggan

What’s the difference between a toboggan and a sled? A sled has runners on the underside; toboggans sit directly on the surface of the snow. Used for recreation or athletic competition today (think luge and bobsled), toboggans served a more practical purpose for the native people who invented them.

Toboggans were used to lug heavy loads over long tracts of snow-covered terrain. This was more efficient and less strenuous than carrying the loads on backs or dragging them on the ground.

Early toboggans closely resembled the mass-manufactured ones we’re more familiar with. Thin wooden planks were bound side-by-side and curved upward at the front. Horizontal cleats provided durability, though now they tell us where to sit. Cords were strung through the cleats and looped out the front for either humans or dogs to pull.

Toboggans lacked steering, so when racing down a hill or the side of a valley, riders would use their feet for braking and shift their weight to turn. Toboggans greatly improved the ability of Indigenous people to travel and trade over long distances, expanding exploration and connecting communities.

— Richard F.J. Wood

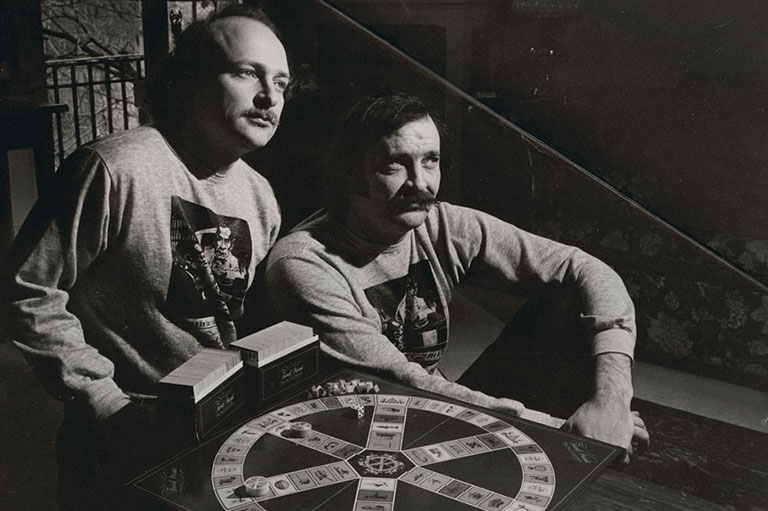

Trivial Pursuit

A pair of Canadians turned a love of trivia into the bestselling board game Trivial Pursuit.

Friends Chris Haney, a photo editor at the Montreal Gazette, and Scott Abbott, a sports journalist with The Canadian Press, gathered December 12, 1979, for a friendly Scrabble tournament but noticed that their new game was missing a few of its letters. Appalled at the expensive price of the incomplete game — a whole eleven dollars — Haney decided there must be a great amount of money to be made in board games.

The pair conceived their new game in just forty-five minutes.

After scraping together investments from friends, family members, and colleagues, they trademarked Trivial Pursuit on November 10, 1981, and licensed the game to Selchow and Righter in 1982. The first thousand copies were released in Canada.

Trivial Pursuit reached its peak of popularity in 1984, when 20 million copies were sold.

In 1988, the game was sold for $80 million to Parker Brothers, now part of Hasbro. As of 2010, Trivial Pursuit had sold nearly 100-million games in twenty-six countries and had been translated into seventeen languages.

— Katherine Dow

Yahtzee!

What better way to enjoy our summer patio weather than to have people over to play a few board games? Canadian inventors seem to have the leading edge in slacking off, having created some of the most popular board games of our time. Yahtzee, for instance, was invented in 1954 by a wealthy Canadian couple who played the game with friends on their yacht.

It was befittingly christened “The Yacht Game.” Players take turns rolling five die, trying to achieve certain rolls with different assigned point values. The word “Yahtzee” is called out whenever a lucky player rolls the same number with all five die.

According to Hasbro, about 100 million people worldwide play Yahtzee on a regular basis. Other games invented by Canadians include Trivial Pursuit (1982), Balderdash (1984), Scruples (1984) and Pictionary (1986).

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!