A Brief Parole

On July 24, 1955, Paul Robeson was in good spirits. A photograph from his concert at the Peace Arch Park that day shows the great African-American singer and political activist playfully peering around the stone boundary marker on the international border between Washington state and British Columbia. He is smiling and waving, as if to laugh off the travel ban that had prevented him from leaving the United States for the previous five years.

Robeson, who was born in 1898, was one of the most accomplished Americans of his generation. His father was a runaway slave who became a minister in the Presbyterian Church in New Jersey. His mother came from a family of free blacks active in anti-slavery agitation. As a young man, Robeson distinguished himself as an athlete — he was a star college football player — and as a scholar — he was the first black man to graduate from Rutgers University, where he delivered the valedictory address in 1919. He went on to finish law school at Columbia University and then had a celebrated public career on the stage, including long runs as Othello in London and New York, where he was the first African-American to play Shakespeare’s tragic hero in more than a century.

But Robeson became most famous as a gifted concert artist. His bass baritone filled the world’s largest concert halls, and his recordings of classics, spirituals, show tunes, and folk and labour ballads were among the bestsellers of their time. His acclaimed 1939 radio performance of the folk cantata “Ballad for Americans” was a condensed version of American history that captured the unresolved tensions between the American dream and the American reality.

It was no surprise that by the 1940s, his honours and awards included a prestigious citation, from what was then called the National Negro Museum, for “courage and devotion to the ideal upon which American democracy was founded.” He also received the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Spingarn Medal in 1945, “for distinguished achievement in the theatre and concert stage.”

As most of the world also knew, in 1950 the American State Department had suspended Robeson’s passport, stating that it was not in the interests of the United States for him to travel abroad. Robeson was considered too fierce a critic of racism at home and of imperialism abroad. And, in the context of the emerging Cold War, he was too sympathetic to calls for world peace and nuclear disarmament, which were skeptically called “the Soviet peace offensive.” Robeson’s passport applications were routinely refused, and border agents were instructed not to allow him to leave the country. The effect was to arrest Robeson’s career as a performing artist and to reduce his profile as an activist. He had become, as Robeson put it, “a prisoner in his native land.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

But in the summer of 1955 he was optimistic. It was the fourth year Robeson had come to the international border to perform at an annual union-sponsored picnic. Thousands of people gathered on the Canadian side to hear him sing and speak from the back of a flatbed truck parked on the edge of the boundary line. This year Robeson seemed to perform with more than his usual depth of feeling, as if he sensed that this could be the last of the Peace Arch concerts. In program notes, he had written that he saw signs of change in the political climate in the United States: “I look forward to an early victory in my long struggle to win the right to cross over the border at which we gather.”

Robeson had reason to be hopeful. Only a few days earlier, the State Department had decided to grant permission for Robeson to go to Canada, travel that would not require a passport. It was a small concession, but he regarded this as a first step in his return to the world stage. At the Peace Arch, Robeson told his audience that he was looking forward to making a coast-to-coast Canadian tour in the near future. At the time, there were no objections from the Canadian government. When the matter was discussed at a federal cabinet meeting on July 28, it was agreed that Robeson could be admitted to Canada if an application was made.

When Robeson stepped onto the stage at Massey Hall for his concert, he received a deafening ovation from the overflow house of 2,800 people.

Toronto was the obvious place for him to start. Robeson had played there on repeated occasions in the 1940s and knew that he would have an eager audience. Also, he was determined to travel north to Sudbury, Ontario, to perform at the national convention of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, the union that had started the Peace Arch concerts after he was prevented from attending their 1952 convention in Vancouver.

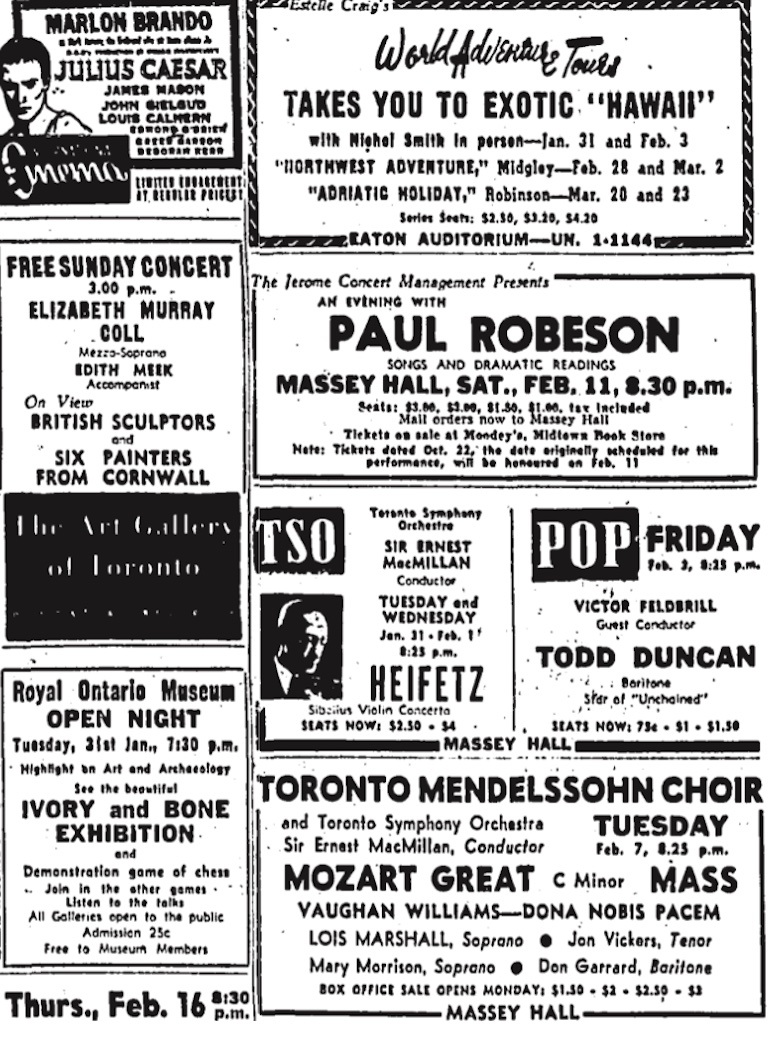

In preparation for the visit, a Montreal-based agency, Jerom Concerts and Artists (sometimes spelled Jerome), had booked Toronto’s premier venue, Massey Hall, for October. The event was billed as “Mr. Robeson’s first concert appearance in Toronto since 1949.” A few weeks later, Robeson’s health took a bad turn, and plans were delayed while he underwent an operation. The fifty-seven-year-old Robeson was hospitalized for several weeks, but he did not forget his Canadian plans. He wrote to a Toronto associate in December saying, “I am looking forward to the early opportunity I shall have to greet you and all my other Canadian friends in person.”

In January 1956, doctors pronounced Robeson ready to resume public activity. Notices for a concert at Massey Hall on February 11 appeared in the newspapers. Meanwhile, the Mine Mill union had changed the date of its convention to make it possible for Robeson to attend. He arrived at Toronto’s Malton Airport on February 7 and entered the country without incident. It was his first time outside the United States in more than five years.

Some details of the visit were recalled years later by Lloyd Brown, who was acting as Robeson’s manager at the time. Brown was an African-American novelist and editor who was assisting Robeson on a short autobiography that would be published in early 1958.

He has recalled that the Canadian authorities originally issued a travel permit for five days, expecting them to leave the country the day after the Massey Hall concert. “If we were getting out of prison in the United States,” said Brown, “it was going to be a brief parole.”

Once again, it was Mine Mill to the rescue. They were expecting Robeson to attend their meetings at the end of February, and after the union intervened Robeson received an extension for a full month. It came, however, with a proviso that he not make any “public addresses or appearances other than those authorized.”

When Robeson stepped onto the stage at Massey Hall for his Saturday night concert, he received a deafening ovation from the overflow house of 2,800 people. For those who remembered him from earlier visits, Robeson looked thinner, evidently more frail than in the past, but still with the sure step of the football player he had been in his youth. And as far as the audience was concerned, he had the same rich and expressive voice: forceful, elegant, grave, gentle, always impassioned.

Robeson began with a reading of the words to “O Canada,” a kind of acknowledgement of appreciation to the audience. The program continued with one of his favourite spirituals, “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel.” This was followed by a characteristic mix of songs from his wide repertoire: Beethoven, Schubert, Mussorgsky, and Dvorak flowed easily alongside lullabies and spirituals, folk and labour ballads. He also included a Canadian selection, “Un Canadien Errant,” a song of exile from the aftermath of the 1837 rebellion. In the course of the evening, Robeson sang in English, French, Russian, Chinese, Persian, and Yiddish.

His introductions made no secret of his political views. Between songs, a police agent in attendance reported, Robeson “stated that he had worked for Peace, and also so that his people, wherever they may be, in Africa, India or America, could be free.” Introducing a Chinese song, Robeson remarked on the universality of music, stating, according to the police notes, that “East is not East, and West is not West, and the Twain can meet.” And in some songs, the agent reported, “the words were re-arranged to produce obvious Communist propaganda.” It is not surprising to learn that Robeson was under surveillance. His hotel phone was tapped, but security forces seem to have discovered nothing more interesting than a round of visits to friends, theatres, restaurants, and bookstores.

Between those two public concerts, Robeson also made an impromptu visit to perform for children at the United Jewish People’s Order.

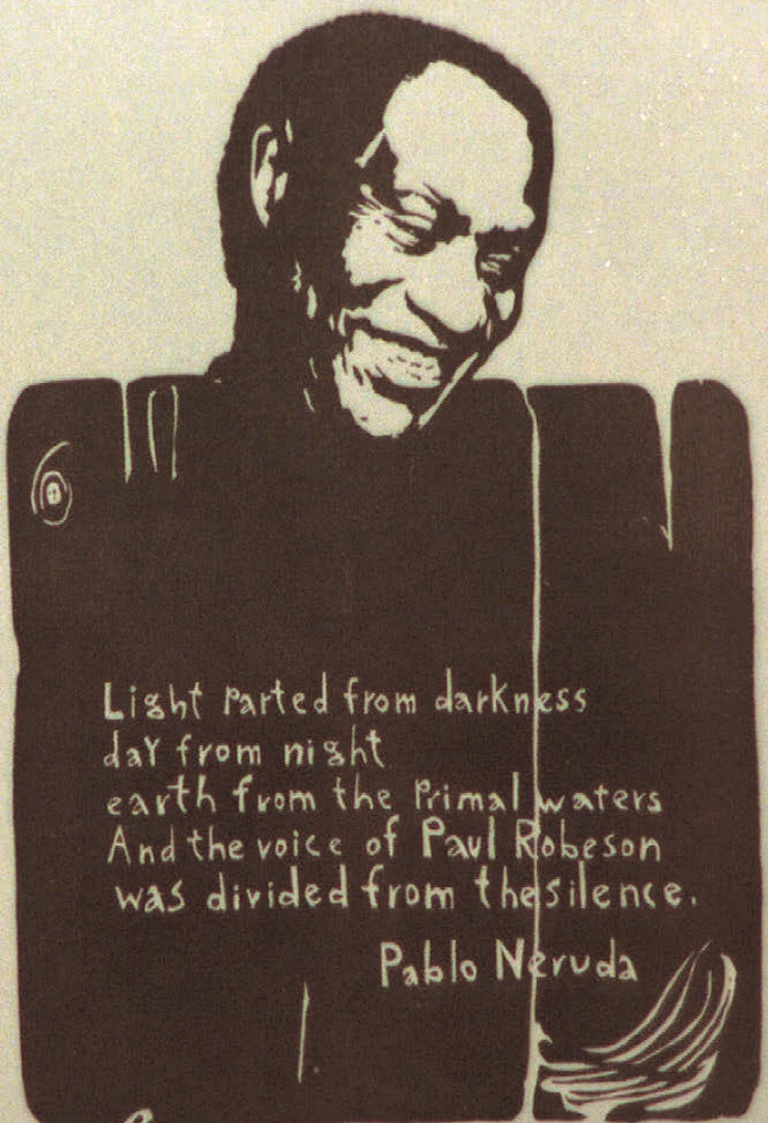

One highlight of the evening was Robeson’s signature song, “Ol’ Man River,” which he had first performed in the London production of the musical Showboat in 1928. His personal version had evolved to replace the original theme of resignation with stronger words of resistance: “I keeps laffin’, Instead of cryin’, I must keep fightin’, Until I’m dyin’, And Ol’ Man River, He’ll just keep rollin’ along!” The program ended with recitations from Shakespeare’s Othello and Pablo Neruda’s poem “Let the Rail Splitter Awake.” His two encores, the plantation workers’ song “Water Boy” and the labour anthem “Joe Hill,” pointed to the legacies of racial oppression and labour struggle with which Robeson identified so closely. The concert ended with clapping, cheers, and whistles, and supporters described it as a triumph.

“It is doubtful any Massey Hall artist ever experienced the sheer adulation expressed by the capacity audience,” wrote one reviewer — who also referred to Robeson disparagingly as a “once-great artist.” Another critic commented, sourly, that the audience “appeared to be entirely satisfied with everything that went on, but I thought that neither the music nor the propaganda was particularly effective.” Obviously the concert was both a cultural and a political occasion, and whatever the critics said the audience was more than satisfied.

For Robeson’s next public event, the union convention in Sudbury, there was trouble arranging to rent the Sudbury Arena, the community’s largest public space. It was the kind of problem Robeson had often encountered in preceding years under the blacklist. When the application came before city council, the mayor, who had made inquiries about Robeson with the Department of Justice in Ottawa, objected to allowing use of the municipal facility for Robeson’s concert. Although Sudbury was a Mine Mill stronghold, with the union representing thousands of workers at International Nickel and Falconbridge, Cold War tensions were running high, and Mine Mill was regularly under attack as a “red” union.

As a result, the concert was moved to the union hall, where Robeson performed much the same set as in Toronto, again to extended acclaim from the audience. There was also a dissatisfied critic, who wrote that there was only minor applause when Robeson performed a difficult classical passage but that as soon as he started “Joe Hill” audience members rose to their feet. “These miners liked Paul singing ‘Joe Hill’ more than Mussorgsky!” Brown later recalled.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Between those two public concerts, Robeson also made an impromptu visit to perform for children at the United Jewish People’s Order, the Toronto branch of a leftist social and cultural fraternal organization. On previous visits, Robeson had performed with the Toronto Jewish Folk Choir, and he was happy to renew the friendship. As his ostensible manager, Brown wanted to keep Robeson in good form for the trip to Sudbury. Accordingly, when he agreed to bring Robeson to the United Jewish People’s Order hall, he warned that Robeson would say a few words and sing, but no more than one song. As Brown has recalled, Robeson completely ignored the agreement. “He spoke, he sang at length. I remember the sweat was pouring down his face, and afterwards he spoke to the children. He did a lot of singing, and I was just so worried.”

When they returned to the hotel, Brown related in a later interview, “Paul asked me, ‘What did you think of my singing?’ I said, ‘Paul, all I could think of was I was worrying.... I really didn’t notice.’ ‘Well,’ he says, ‘you should have noticed. I sang better there than I did at Massey Hall. When I sing to an audience of children, I am much freer than at any other time. Children will never hurt you.’” Robeson went on to explain how strongly he felt about giving memorable performances for children. “Chances are, these children are never going to hear me again. I want them to remember me at my best. I want them to really remember how I sang. I want it to be a lifelong impression for them.”

The success of the Massey Hall concert encouraged his Canadian sponsors to go ahead with plans for a full tour across Canada. As announced in early April 1956, the itinerary included seventeen cities, beginning with Montreal and Ottawa and ending in Vancouver, with concerts to be spread over five or six weeks in April and May. Other places on the tour included the Ontario cities of Windsor, London, Hamilton, Welland, Timmins, and Fort William as well as Winnipeg, Regina, Saskatoon, and Edmonton.

Robeson’s reception in Canada had given him a good deal of satisfaction, and on his return to New York he wrote to friends in Britain about the great warmth of the Canadian audiences. He soon turned his attention to preparing his repertoire and rehearsing, intent on renewing his performance skills ahead of the coming tour. His son purchased a reel-to-reel tape recorder and a supply of tapes for Robeson to use in reviewing his work.

Only a few days before the first of two concerts at the Windsor Hotel auditorium in Montreal, the tour was called off. Jerom Concerts announced that the Department of Citizenship and Immigration was refusing to allow Robeson to enter Canada. A government spokesman stated simply, “He will not be admitted under present auspices.” It was an extraordinary situation, said manager John Boyd on behalf of Jerom Concerts, noting that it was fully unexpected in light of Robeson’s recent visit. Moreover, he added, “To our knowledge not a single country in the British Commonwealth would today prevent Mr. Robeson coming in to give commercial concerts.”

The responsibility for banning Robeson rested with Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Jack Pickersgill. He was an ultimate Ottawa insider, having worked as an assistant to prime ministers William Lyon Mackenzie King and Louis St. Laurent before entering cabinet. “Clear it with Jack” was a common byword on Parliament Hill, and few in government were prepared to second-guess him. At a cabinet meeting on March 29, 1956, Pickersgill recommended that Robeson be refused permission for the planned tour, and cabinet duly approved.

After the news broke on April 10, questions were asked in the House of Commons. Pickersgill’s answer was, “It is not the policy of the government to admit known communists to this country.” Robeson, he said, was “a professed communist” who was coming to Canada under “communist auspices.” There was an obvious inconsistency — Robeson had visited two months earlier under the same sponsorship, and with the approval of the same minister and cabinet, who could hardly have been unaware of Robeson’s reputation as a public figure.

There was also the inconvenient fact that, despite allegations, even the American Federal Bureau of Investigation had never been able to come up with proof that Robeson was a member of the Communist Party, even if that were sufficient grounds for exclusion. As for the sponsorship, it was true that the manager for Jerom Concerts was a known communist. Less is known about the company president, Jerome Myers, who was active in leftist theatre and cultural circles in Montreal. At the time of the company’s incorporation in 1955, most of the directors were Montreal lawyers, one of whom later became chief justice of the Quebec Superior Court.

How any of this disqualified Robeson from entering Canada to give concerts was unclear, and there was a small storm of editorial protest around the decision. The Toronto Star was the most vocal, denouncing the ban as “unfair,” “foolish,” “ridiculous,” and “unworthy of Canada’s tradition of political and cultural liberty.” Its editorial cartoon depicted the Robeson decision as a stain on Canada’s reputation for “fair dealing” and “no discrimination.” A much more conservative newspaper, the Toronto Telegram, called the decision a “blunder” that would only give publicity to Robeson and his supporters, noting, “bureaucracy makes an utter ass of itself when, particularly in a land which prides itself on freedom of expression, it thinks it can stop the flow of ideas.”

It remains something of a mystery why Pickersgill changed his mind between July 1955, when he recommended Robeson’s admission, and March 1956, when he decided to refuse him. No doubt Pickersgill understood that a Robeson concert was never just a concert, and perhaps the reports of Robeson’s reception in February had raised concerns about the influence he might have on a longer tour and what controversies might be provoked. It is also possible that Pickersgill wanted to discourage Jerom Concerts from gaining a foothold in the concert business and promoting more undesirable cultural activities. As Canada’s chief gatekeeper, Pickersgill took the view that immigration policies should not be allowed to threaten the “fundamental character” of the country as he saw it.

According to one of Robeson’s close friends, news of his rejection by Canadian authorities was a “heavy blow,” and he soon plunged into a deep depression. Still, the Canadian experience may also have helped to revive Robeson’s determination to challenge his own government. By June, he was answering a summons from the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He surprised friends and supporters with the poise and eloquence of his response to the hostile questioning. Moreover, by the spring of 1958, the outlook was improving. The blacklist was starting to lift, and Robeson’s Carnegie Hall concerts of that year are considered to be among the best recordings in his catalogue.

His passport finally came through, in July 1958, as a result of a narrow five-to-four American Supreme Court decision on the question of whether citizens may be denied a passport due to their political views. Robeson lost no time in packing for Great Britain and left for a hero’s welcome in London. Soon he was playing Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company and again performing for audiences around the world.

It was a relatively short-lived coda to his career, however. Robeson’s health was breaking down, and he was subjected to numerous rounds of what his son came to believe were dubious drug and psychiatric treatments, possibly aided and abetted by American authorities. After he returned to the United States in 1963, Robeson made few public appearances.

While living in Britain in 1961, Robeson briefly, impulsively, thought about moving to Canada, writing about the idea in a letter to a friend. His fondness for Canada was genuine. In an interview during the 1956 visit, he recalled his first concert at Massey Hall in 1929. The appreciation he received encouraged him to continue his career as a performer. He had visited on many occasions after that. And he could never forget the dramatic Peace Arch concerts held in defiance of the travel ban in the early 1950s.

For tens of thousands of Canadians, Robeson had a deep and lasting appeal as the embodiment of a better world in the making. At the time of his death in 1976, many who had seen him perform in the past were able to attend a memorial concert held at Toronto’s Harbord Collegiate. There were also celebrations in Canada in 1998 to mark the one hundredth anniversary of his birth.

In 1958, there had been plans to arrange more Canadian dates for Robeson, but those limited appearances in February 1956 turned out to be his last performances in Canada. It must have seemed ironic to Robeson that the country that enabled him to make his first escape from internal exile in the United States did not wish to extend the welcome any further. For the time being, official Canada had chosen to continue the cultural politics of the Cold War.

CANADA’S COLD WAR

It has often been said that the Cold War started right here in Canada, when, in February 1946, Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko defected from his country’s embassy in Ottawa. His sensational revelations about highly placed Soviet spies throughout the Canadian and American governments shocked the West.

In the frosty war of espionage and threats, however, Canada was never more than a relatively minor force — the ham in the Soviet-American sandwich, as goes the saying attributed to various players, including the Soviet ambassador to Canada and Prime Minister Lester Pearson. In our middle-of-the-road way, we firmly supported the United States even as we managed to avoid the worst of that country’s Cold War paranoia.

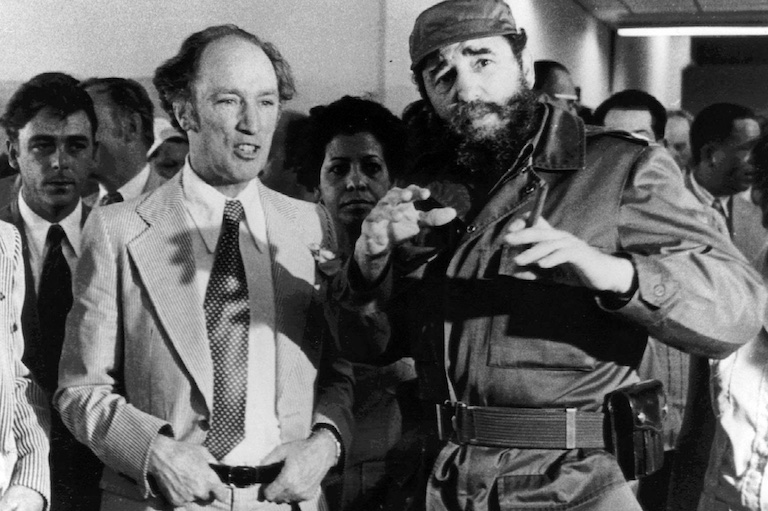

There was no House Un-Canadian Activities Committee, nor did we execute anyone for spying. But Canada was front and centre in the creation of the anti-Soviet military pacts NORAD, the North American Aerospace Defense Command, and NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. When communist forces invaded Korea, we sent more than 26,000 troops, 512 of whom never returned. Then again, when Soviet missiles were discovered in Cuba in October 1962, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker did not exactly leap to the side of a reportedly furious U.S. President John F. Kennedy. In 1976, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau even visited Cuba, hitting it off with the country’s president, Fidel Castro.

Perhaps we got less worked up about socialism and even communism because we’d seen them up close. The socialist Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) — forerunner of the New Democratic Party — formed the government in Saskatchewan in 1944. It also captured almost sixteen per cent of the vote in the 1945 federal election, although it downplayed its left-wing rhetoric during the Cold War. Canada even had an actual card-carrying communist in the House of Commons. Elected in Montreal in 1943 under the Labor-Progressive banner, Fred Rose was arrested and jailed in 1946 for sharing state secrets with the Soviets.

— Nancy Payne

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.