Paving the Way

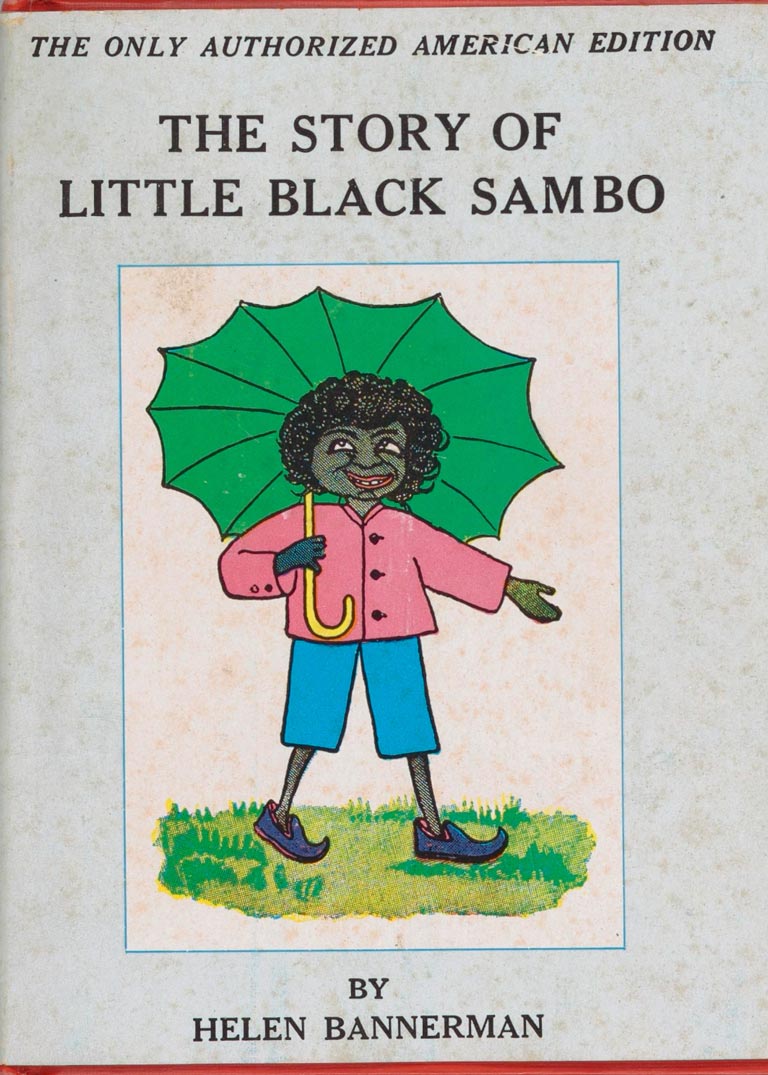

The Gerrish Street Hall in Halifax’s North End filled with members of the Black community and city reporters in late January 1944. Church leader Pearleen Oliver addressed the crowd, condemning segregation. She spoke of a girl who arrived at her doorstep distraught after being denied entry into the Children’s Hospital nursing program, of her brothers fighting overseas and of the hypocrisy of a nation defending democracy abroad while denying it at home. She questioned the promises of future racial equity. Her sharpest criticism, however, was reserved for The Story of Little Black Sambo, then assigned to Nova Scotia’s Grade 2 classrooms. Meant to amuse white readers, the book featured a little boy with purple pants and a pink umbrella running circles around tigers. Such stories, Oliver claimed, presented Black people in “a manner as to destroy respect.”

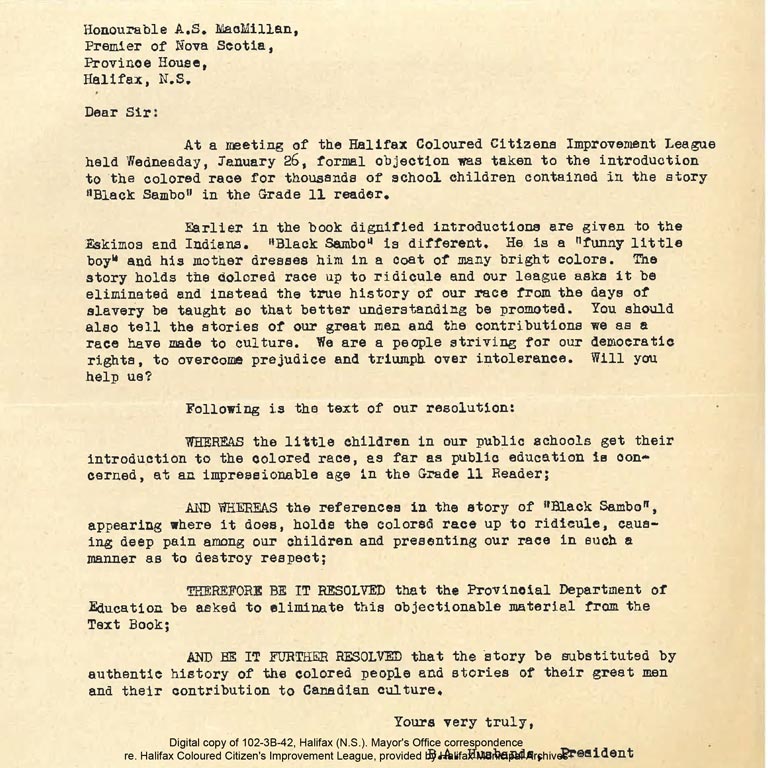

The next day, a local Black man wrote to Nova Scotia Premier Alexander MacMillan, requesting that Little Black Sambo be removed from school textbooks. He asked that the text be replaced with “the stories of our great men and the contributions we as a race have made to culture,” before closing with the declaration: “We are a people striving for our democratic rights, to overcome prejudice and triumph over intolerance. Will you help us?”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Two days later, he sent another letter — this time addressed to his friend, Halifax Mayor John Lloyd. With it, he enclosed the league’s Jan. 26 resolution. The mayor responded promptly, addressing the letter to “Mr. Husbands” and by his title as president of the Halifax Colored Citizens Improvement League (HCCIL). “I wish you every success in your efforts,” he wrote, signing off with “I remain, yours very truly.” For a Black man to be acknowledged in such terms by a white official in a de facto segregated Halifax was rare.

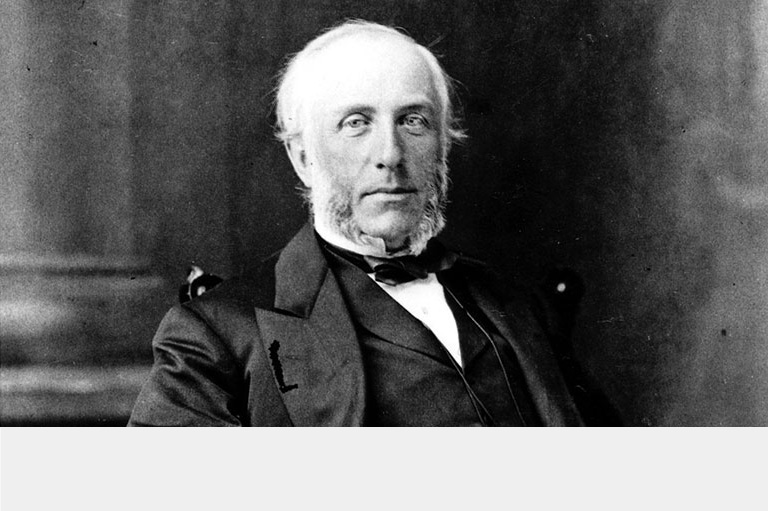

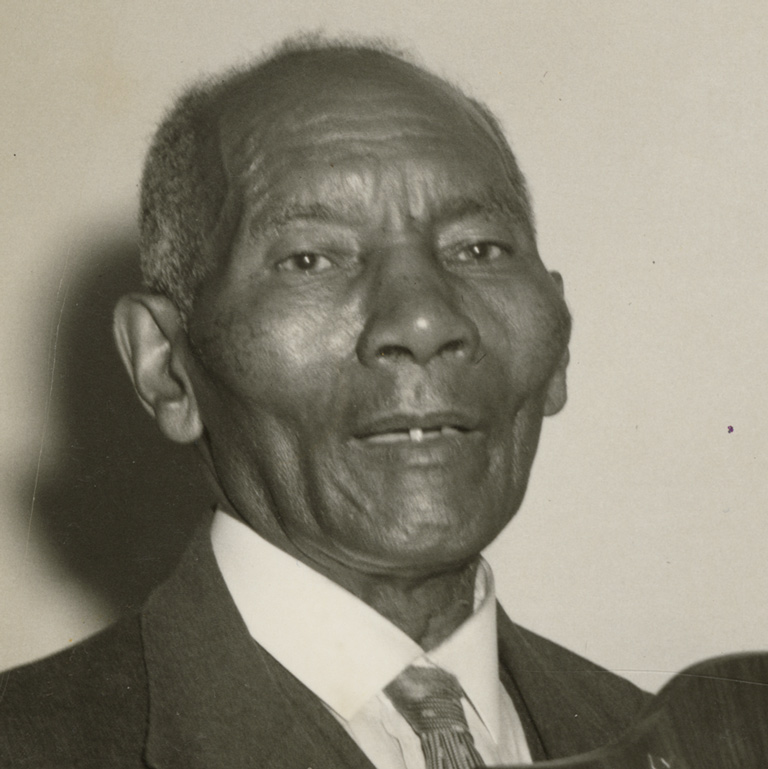

The Black man in question, Beresford Augustus (popularly known as B.A.) Husbands, was a Barbadian expat who spent the better part of seven decades formally challenging the many grievances faced by Black Nova Scotians. Before the rise of the well-known civil rights movements in Canada — often associated with the 1950s and ’60s — Husbands led the HCCIL. Founded in June 1930, the league was designed as an “Organization to further the interest of Canadians who are members of the Colored Race” and was dedicated “to the welfare of underprivileged colored children.” Aimed at uniting the Black community in support of common social and political goals, it advocated with considerable success for better employment and educational and vocational opportunities for Black Nova Scotians.

Husbands was the man for the moment. Arriving in Halifax at the turn of the century, he integrated into the African Nova Scotian community, attending Joseph Howe School and marrying Iris Lucas of nearby Lucasville in 1903. He worked for H.R. Silver, an affluent merchant, before joining the Intercolonial Railway as a porter. By 1930, though, Husbands had built businesses: an advertising agency, a retail store, an employment bureau, a West Indian products import company and a largescale real estate business. He also served as an inaugural executive council member of the Universal Negro Improvement Association’s Halifax branch and as chairman of the Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church trustee board. Through it all, Husbands used his unique position between two Black worlds to push for collective advancement. Today, few remember Husbands’ name, and even fewer know how deeply his league shaped Black civic life in Halifax. However, from 1930 until his death in 1968, Husbands helped pave the way for community self-determination.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

From street lights to civil rights

The year 1929 promised to be horrible for Halifax’s Black community. The Morning Chronicle reported that on New Year’s Day, “a colored man” approached three white children playing on Citadel Hill and, using “a large jack knife,” stabbed seven-year-old Billy Walsh before running off. Police detained several suspects, all of whom were subsequently released when the children said none of them was the assailant. For days, the search went on as local newspapers stoked the tension with such headlines as “Negro Knifer Still at Large.” Ultimately, no arrest was made, but race relations in the city suffered as a result. Husbands publicly denounced the allegations, stating that “no man had anything to do with the affairs.”

The controversy had hardly died out when, a few weeks later, members of the Men’s Teachers Club suggested that Halifax’s schools should reinstate a policy of racial segregation to help alleviate overcrowded classrooms. Initially, the Black community was split; layman James A.R. Kinney and lawyer Joseph E. Griffith condemned the proposal as nothing more than an attempt to introduce “Jim Crow” into the school system, whereas pastors William White and W.J. Davidson agreed that all-Black schooling offered “worthwhile possibilities.” Husbands agreed with the latter, claiming he had been in conversation with “a large number of coloured people” in the city and two-thirds of them spoke in favour of the plan.

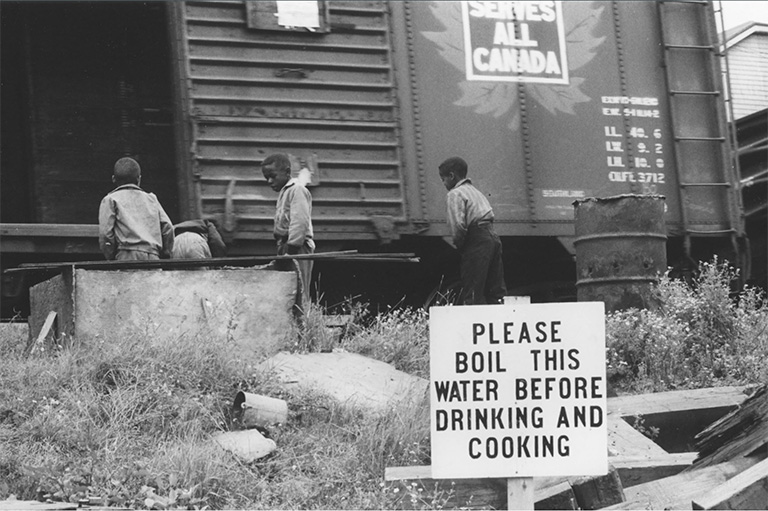

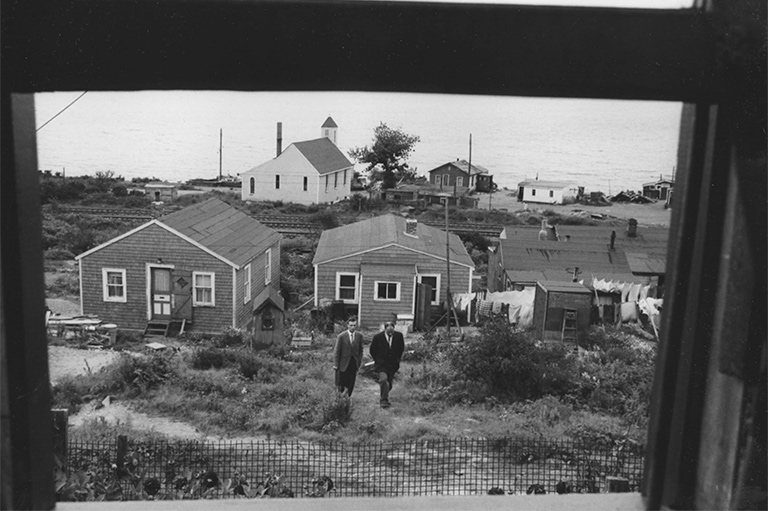

Later that year, the flame of disgruntlement was rekindled when residents of Africville — a close-knit Black community in Halifax long deprived of basic services, such as running water, sewage and paved roads — organized a petition to have street lights installed in their community. Despite being signed by a significant number of community members, the petition was ignored by both the public works committee and the city engineer. Refusing to be dismissed, a delegation led by Husbands brought the issue directly to Ald. Walter O’Toole, who pledged his support. The duo then met with the city engineer, who, according to the Evening Mail, sympathized with the villagers’ request.

Advertisement

“It was through the effort of Alderman W.J. O’Toole, Ward Five representative, and B.A. Husbands, that the petition of the residents of Africville to have streetlighting facilities in the village was not ‘pidgeon-holed,’” the newspaper reported. “Residents of Africville feel that as taxpayers of Halifax they are entitled to proper street lights.”

Though modest in its ask, the petition showed that Black Haligonians were starting to insist that they be treated as equal citizens deserving of basic services, both formally and publicly. They sought a civic voice. Recognizing this collective need, Husbands and other “leading colored citizens” publicly announced their intention to form an organization then called the United Club in an Evening Mail article only a month later. Open to all members of the Black community in both Halifax County and across Nova Scotia, the group was explicitly non-sectarian, a first in the 300-year history of the African Nova Scotian community. In its early stages, the organization secured a building in a central location with clear goals to renovate it for “social, athletic and community purposes.”

The league and the fight for equality

From the United Club arose the HCCIL, formally established at the Halifax Board of Trade rooms in June 1930. More than the typical non-profit, it became, under Husbands’ guidance, Nova Scotia’s first sustained experiment in Black civic politics.

In his book The Nova Scotia Black Experience Through the Centuries, a comprehensive account of Black presence in the province, local historian Bridglal Pachai describes Husbands as “the father of incipient Black politics in Nova Scotia,” noting that before 1938, no other secular leader had appeared. In those early years, the league and its president were virtually synonymous — “as a sort of one-person show.” Through Husbands, the league pursued equality as a set of tangible demands: cultural recognition, equal access to vocational and educational opportunities, and the right to live in dignity.

To achieve those goals, the league organized its general membership into subcommittees and project designations — comprising the Halifax North Cultural and Recreation Youth Centre, Colored Men’s Conservative Social and Athletic Club, the Women’s Auxiliary Committee and the Recreation and Entertainment Committee — which allowed executive members to better advocate for the local Black community. Deeply troubled by the high unemployment rates among Black youth and the lack of representation in city governance, for example, Husbands wrote to city council criticizing the lack of opportunities, using his title as president of the Colored Men’s Conservative Social and Athletic Club: “I would draw attention to the fact that there is no representative of the colored race in any of the local civic departments. We have in the colored community many people who have recently graduated with distinction from high schools with the aim in view to secure employment. Their efforts in this direction have been unsuccessful. We feel that when any vacancies arise in the offices in city hall or elsewhere under the supervision of the city, our people should be given an opportunity to apply for same, and trust that our appeal will be given most careful consideration. Our young people do not wish to continue to exist on relief. They want employment.”

After these initial actions, Husbands and the league maintained a strict emphasis on the importance of Black education across the province. After league members convened at Gerrish Street Hall to denounce the racist imagery in Little Black Sambo, Husbands lent his full support to Pearleen Oliver in her campaign to desegregate the nursing profession, aligning the league with her call for equal access to professional training for Black people. Only two months later, their pressure ushered in change: Premier MacMillan pledged to remove the story from future editions of the curriculum, and two Black women — Ruth Bailey and Gwennyth Barton — were admitted into a Canadian nursing program for the first time.

The league took children on tours of industrial establishments in Halifax and Dartmouth to help mould their futures. It also offered both academic and fitness programs during the week and, under Husbands’ leadership, brought in guest speakers to inspire students. Seeing role models who looked like them encouraged young people to stay in school and imagine broader career possibilities. “The combined classes of boys and girls of the Halifax Colored Citizens Improvement League … were treated to a talk by Bredu Pabi,” the Mail-Star reported on Oct. 29, 1955. “Mr. Pabi comes from the Gold Coast [present-day Ghana] of Africa and is studying law at Dalhousie University.”

By 1948, the league had built an impressive circle of supporters drawn from the city’s white leadership, appointing well-known lawyers, doctors, aldermen and even the chief of police to an honorary board of advisers. In a letter dated June 3, 1952, Husbands formally invited Mayor Art Donahoe to take on the role of honorary president. “You will kindly note on this letterhead,” he explained, “that we have as our Honourary President Ex-Mayor G.S. Kinley, who has fallen in line with several other Mayors of our City, by doing us the honour of allowing us to carry his name in that position along with the other gentlemen mentioned.” By placing influential white politicians into symbolic positions, Husbands acquired their attention and support.

Following decades of advocacy, the league entered the 1960s confronting the familiar issues plaguing Africville. When the Halifax City Council released a report in July 1962 recommending the elimination of the neighbourhood, community members convened to confront the threat, with Husbands at the forefront of the discussions. He also wrote a series of public appeals in the Mail-Star’s letters to the editor section. In one, Husbands equated the Africville situation to both the treatment of serfs in feudal Europe and the newly coined term “apartheid.” He argued that the term “freedom” hadn’t been fairly applied to Blacks in their immigration and settlement in Nova Scotia. Underlying this, however, Husbands advocated for fair treatment of taxpaying Africville residents and that their relocation be handled with dignity.

“I feel that possibly the city could allow the present inhabitants of Africville a portion equal to the present market value of their interest in the land and apply that portion to the cost of the new dwellings,” he wrote. “By this I mean the citizen of Africville would be permitted to swap his interest in the present community for a sizeable equity in the new, well-serviced, and well-constructed community west of MacIntosh Street. The first objection to a proposal such as this is that the city would be catering to a specific class and type of citizen. Does not the same thing exist in Mulgrave Park? Would not the same thing apply to Uniacke Square? In conclusion, I would like to suggest that what is good for the Jacob Street area is as equally good for the Africville area, but at the same time I feel that where the people of Africville have strived within their means to provide shelter for their families they should be given the same opportunity to better themselves and at the same time, better the community as a whole.”

Even on the global stage, the league made its voice heard. In March 1965, the league sent a message of support for federal voting rights legislation to the U.S. secretary of state following the violent attacks on protestors in Selma, Ala. This act of transnational solidarity bound the Black Nova Scotian struggle for equality to the broader diasporic freedom struggles of the ’60s.

The path Husbands cleared

Fondly remembered by many generations of citizens, the league achieved many substantial victories for the Black community. When the George Dixon Recreation Centre opened in 1969, it carried forward a vision first voiced by Husbands more than 30 years earlier. Later organizations such as the Colored Education Centre (1938), Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (1945) and the Black United Front (1968) followed in Husbands’ trailblazing footsteps by providing Black people with additional institutional platforms to mobilize and advocate for themselves.

Before the colour line had been broken in the nursing field, Husbands was once admitted to Victoria General Hospital, where the nurses who attended to him were all white. He asked league secretary Edith Gray to bring flowers for each of the nurses. When she argued, Husbands retorted: “I am a Black man here. I will pave the way for the next Black man who will come after me.” Such stories reinforce the sense that Husbands’ greatest contribution was the example he set.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement