Home Aid

In January 1946, a group of Second World War veterans staged a headline-grabbing protest that was unprecedented in the history of a gritty west coast metropolis.

Thirty members of the New Veterans Branch of the Royal Canadian Legion occupied the old Hotel Vancouver, a hulking six-hundred-room structure built by the Canadian Pacific Railway in an Italianate style. Located at West Georgia and Howe streets in Vancouver’s business district, the hotel had been known for years as “the palace of the people” and featured destination bars, restaurants, and shops, while boasting such famous guests as Charlie Chaplin, Winston Churchill, and Babe Ruth. But the CPR had constructed a larger, more modern replacement not far away and wanted to divest itself of this older and now vacant property.

For more than a year before the occupation, Vancouver’s housing crunch had become steadily worse. The empty hotel served as a stark reminder of the plight of veterans who were then facing eviction from temporary purpose-built wartime housing. What’s more, the housing shortage had stirred up tense feuding among provincial political parties, the city, and the federal government. A federal estimate put the city’s housing shortfall, as of mid-1945, at twenty-five thousand units. Housing activists were calling on the government to build five thousand new dwellings and to acquire the hotel so it could be transformed into a hostel for homeless veterans. Picketers carrying signs with angry slogans — one read “Empty Hotel plus Homeless Veterans equals Civic Disgrace” — protested in front of the hotel, and finally the band of legionnaires took matters into their own hands. “

Led by sergeant-at-arms Bob McEwen, a ‘shock troop’ walked into the hotel lobby and informed two lone army guards that they were taking possession of the building,” wrote B.C. historian Catherine Jill Wade in her 1986 account of the incident. “They wired the news to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King. The ‘occupying force’ drew up strict house rules to govern behaviour and organized committees to handle food, billeting, recreation, and hygiene. They hung a I5' x 3' [five-metre by one-metre] banner on the hotel’s Granville Street wall that read ‘Action at Last / Veterans! Rooms for You. Come and Get Them.’ By Saturday evening, 100 ex-service men and women and their dependents had registered at the hotel.” Hundreds more arrived within the next few days.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The Hotel Vancouver incident played out at a moment when the federal government’s piecemeal approach to meeting the housing needs of almost a million returning veterans — as well as tens of thousands of war brides from such countries as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands — had become a litmus test of Canada’s ability to navigate a social crisis.

Through the Depression and then the Second World War, Canada’s home-building industry had been virtually gutted, first by economic conditions and then by labour and material shortages. New construction dropped from 50,200 units in 1928 to 14,000 in 1932, while urban home ownership declined from forty-eight per cent to forty-one per cent from 1921 to 1941, according to a 2024 paper in the Journal of Planning Perspectives.

Beginning in 1941, Ottawa became active in constructing what it considered to be temporary rental housing for the families of people working in wartime industries. The veterans’ return — 620,000 in 1945 and 1946 alone — turbocharged the housing crunch. Indeed, federal officials anticipated this problem as early as 1944, when housing and planning experts began studying the conditions that awaited those who would come home from overseas.

In many larger cities, these experts noted, lower-income families lived in so-called slums, warrens of overcrowded working-class row houses that they said should be condemned and demolished. Tens of thousands of families were forced to double up, while the number of those who rented their dwellings had risen steadily — a worrisome trend in a country that attached enormous social and economic importance to home ownership.

The task of confronting this housing crisis wasn’t merely a matter of a construction catch-up. Ottawa’s decision making in that period was also informed by fraught ideological debates about the state’s role in housing, financing, architecture, and community planning. In fact, the choices made first by the King government and then by Louis St. Laurent’s after 1948 defined the very form and evolution of Canada’s postwar urban and suburban development while amplifying the disenfranchisement of returning Indigenous veterans. It was a “very consequential” period, says J. David Hulchanski, a University of Toronto professor of housing and community development. “Decisions were made at that time which are still with us today, which is to maximize the amount of market housing. Today, ninety-six per cent of Canadians have to go to the market for their housing, either to rent or to buy.”

The story of how Canada navigated the postwar housing crisis obviously has resonance today, with all sorts of overlapping elements — the proliferation of overcrowded rental housing and construction-labour shortages, for example — and perhaps even some common solutions.

Tens of thousands of families were forced to double up, while the number of those who rented their dwellings had risen steadily.

Advertisement

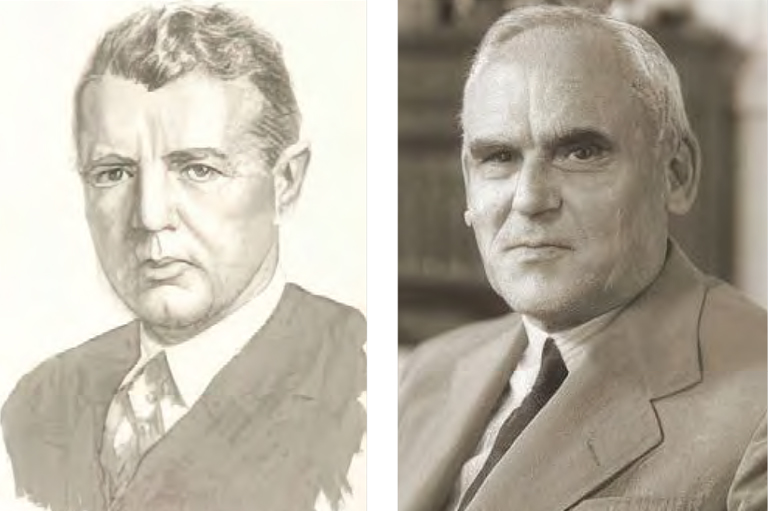

Joseph Pigott was something of a rarity in Canadian business circles during the war: a wealthy builder who had not only survived the Depression but was running one of the country’s most successful construction firms, in Hamilton. In 1941, the King government tapped him to run a new Crown corporation called Wartime Housing Ltd. (WHL), which had a mandate to build rental housing for the people working in wartime industries as well as for veterans. Pigott was “very forceful, very hard-driving,” comments Queen’s University planning historian David Gordon. “Just what C.D. Howe [King’s so called ‘minister of everything’] needed.”

The following year, Ottawa passed the Veterans’ Land Act (VLA), which also targeted the housing shortage, but from a rural perspective. After the First World War, the federal government had tried to set up returning soldiers on large fallow lots and to teach them to farm — an experiment in social engineering that failed for many people who couldn’t get the hang of agriculture. The new act provided financing assistance, in the form of a partly forgivable loan, for two-acre (0.8-hectare) parcels, including lands on the urban fringe upon which veterans could build homes (sometimes by themselves) and grow a modest amount of food to supplement other income.

The VLA led to the construction of thousands of homes in semi-rural places like Ancaster, Ontario, outside of Hamilton. By the late 1940s, according to a history of the program written by McMaster University geographers Tricia Shulist and Richard Harris, two-thirds of homes were being built by the owners themselves, with technical assistance from VLA officials who had an explicit mandate to teach these veterans construction techniques and to provide expert assistance.

The program’s administrators extended no such support to returning First Nations veterans. According to briefs submitted to the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Indian Affairs Branch inserted itself into this policy file, asserting that VLA benefits not be made available to returning Indigenous veterans, who were meant to remain on reserves. Ottawa later tweaked the act to allow for smaller loans for on-reserve Indigenous veterans, but with the funds “paid to the Minister of Mines and Resources who shall have the control and management thereof on behalf of the Indian veteran.”

In some cases, these veterans could receive a grant only if they agreed to move to certain reserves. “What happened in a lot of cases, especially out west and the Prairies in Alberta, [is that] a lot of reserve land was expropriated and given to returning vets,” says (retired) Sergeant Wendy Jocko, former Chief of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation. Her own father, who served in Scotland, and five of his brothers simply weren’t told. “They were not aware of certain programs or entitlements,” Jocko says. “And that’s a real shame.”

As for WHL, between 1941 and 1947 Pigott oversaw an impressively efficient operation that assembled land, constructed over thirty thousand temporary homes, and also built fire stations, schools, and community centres. The WHL houses tended to be modest — bungalows with no basements, built according to template designs — and situated near factories making commodities such as munitions. Pigott and his board of volunteer advisors turned WHL into a highly decentralized organization — there were fifty-one field offices overseeing projects in seventy-three municipalities across Canada — that also managed this far-flung portfolio of rental stock.

Indeed, as Jill Wade documented, Pigott had a vision for the future role of WHL, which he shared with Ottawa: “If the Federal Government has to go on building houses for soldiers’ families; if they have to enter the field of low cost housing which it is my opinion they will undoubtedly have to do, then there is a great deal to be said in favour of using the well-established and smoothly operating facilities of Wartime Housing to continue to plan and construct these projects and afterwards to manage and maintain them.”

Officials in the Liberal government, however, had other ideas.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In 1944, an advisory committee to the federal government released a hefty report on housing and community planning as a piece of the postwar reconstruction process — a study that came to be known colloquially as the Curtis Report, after the committee chair, Clifford Curtis, a professor of economics at Queen’s University. As they thought about the future of housing and planning, Curtis and others involved were highly influenced by emerging town planning-ideas from the United Kingdom and the United States — approaches that focused on the neighbourhood as the ideal unit of development and included features such as curvilinear streets or cul-de-sacs.

Curtis’s report also focused intently on scale and on the mechanics of financing. He said Canada needed 606,000 new urban units and 125,000 new farmhouse units in the first decade after the war. The report went on to recommend that this massive goal be achieved through the creation of a new entity — the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) — that would assemble land, write mortgages, and even counsel would-be developers on the proper techniques for creating modern subdivisions. Curtis’s committee recommended that the federal government authorize thirty-year, five-per-cent mortgages and provide a backstop, in the form of mortgage insurance, that would remove any lending risk for banks.

While the government equipped this new Crown corporation with the tools it needed to defray virtually all the financial risk for nascent builders, Hulchanski says the ideological thrust of the CMHC policy was to leverage the private market to produce new housing, both for returning veterans and for a growing population. The agency would absorb WHL, with its large portfolio of rented homes, and then sell them off, either to the existing tenants or to investors. Despite Pigott’s advocacy, the Liberal government had no intention of remaining in the public-housing business, which carried the unwelcome taint of socialism in a period marked by anti-communist politics. Unsurprisingly, Ottawa hired an insurance-industry veteran, David Mansur, to serve as the CMHC’s first president.

The wrinkle in this narrative involves one of Mansur’s early hires, a British-born planning reformer and academic named Humphrey Carver, who joined the CMHC in 1948 as a research advisor. A proponent of the garden cities approach pioneered by British planner Ebenezer Howard as well as more modernist community design, Carver regarded his muscular agency as a way of promoting state-of-the-art planning ideas tailored to the car- and nuclear-family-oriented postwar recovery. Many of the communities that Carver’s team designed still exist in cities across Canada, from Renfrew Heights in Vancouver to Colonial Park in Lloydminster, Saskatchewan, and Topham Park in Toronto’s East York district.

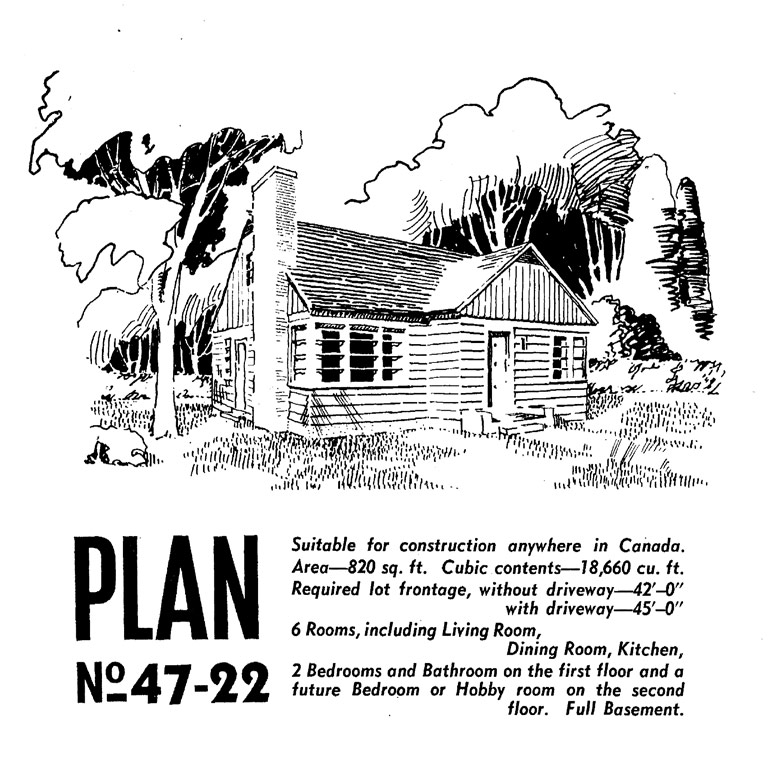

By today’s standards, the CMHC of that period was extraordinarily prescriptive, dictating planning regulations to provincial and municipal governments, acquiring large tracts of land, and assembling contractors to do the work. Samuel Gitterman, a Montreal designer, signed on to oversee an ambitious architectural program to complement the planning, filling numerous “pattern books” with templates for various types of homes, from very basic bungalows known as “strawberry boxes” to somewhat more elaborate bungalows and back-splits. Homebuyers who wanted to qualify for CMHC financing could select their home’s floor plan from one of the CMHC’s pattern books and then buy the blueprint for it for ten dollars. Carver, says Queen’s University’s Gordon, distributed almost a million copies of those catalogues through the CMHC’s extensive network of field offices. Their ubiquity explains why certain types of virtually identical postwar houses can be seen in communities across Canada.

Gordon adds that one of the reasons Canada’s postwar suburbs are somewhat denser than their American counterparts is because Carver advocated for community-planning models that tended to be more space-efficient than the subdivisions that sprang up across the U.S. He knows this trait from first-hand experience, as from 1960 to 1966 his family lived in Oromocto, a CMHC project next to CFB Gagetown in New Brunswick, not far from Fredericton. It was completed in 1958.

“My father served in Korea, and I was an army brat for a while,” he says of his family’s decision to locate at Oromocto. The Gordons lived in a semi-detached house, known in the CMHC’s catalogues as a “JJ/54/T.” The neighbourhood had abundant green space and trails, with two anchors — a brand new shopping mall and a public-school complex — anticipating the kind of planning that informed Don Mills, an entirely privately funded Toronto subdivision often considered to be the first true example of postwar suburban planning in Canada. “I could walk to my elementary school without crossing a major street,” he recalls. “It was a great place to be a kid.”

Jocko’s family, on the other hand, enjoyed no such perks. After the war, her parents moved from Madawaska to Pembroke, Ontario, working in the local lumber industry. They could never afford a home, and Jocko and her sister, Leona, along with their brothers Mark, Paul, and Sandy, were removed from their parents’ care for several years during the Sixties Scoop. Jocko is not aware of any kind of compensation for the thousands of Indigenous veterans who fought for Canada but were denied the housing programs provided to so many others. “I think an apology came,” she says. “But all the veterans were dead [by then], so it was too late even to hear an apology, if there was one.”

Montreal designer Samuel Gitterman filled the numerous pattern books with templates for various types of homes.

In some ways, Ottawa’s response to the current housing crisis is more modest because past intrusions into provincial and municipal jurisdiction wouldn’t fly today. However, there are certainly echoes, from the rhetorical urgency expressed by federal politicians of all stripes in the aftermath of an inflationary crisis to fine-grain details, such as Ottawa’s decision to reintroduce pattern books — featuring updated designs — as a way of speeding up approvals. There’s one other important parallel: pent-up demand from a massive demographic bulge — the millennial generation, which, like the parents of the baby boomers of the postwar era, desperately needs better housing. However, in a climate crisis we certainly can’t afford to solve a twenty-first-century housing crisis with low-density suburbs, no matter how progressively they might be planned.

Hulchanski and earlier historians like Jill Wade suggestively point out a crucial policy common denominator, which is that after the war, like today, governments looked to the private market for solutions to severe housing crises. Yes, there have been periods when governments saw fit to build social housing — the WHL’s run during the war years, for example, and then the surge of funding for subsidized social and co-op housing in the 1960s and 1970s.

But Ottawa has cleaved to a market-driven policy for decades, with scant evidence of a change in direction, despite the hardships that many Canadians, especially younger people, now experience — as did their grandparents after the Second World War. “Here we are,” says Hulchanski. “Does that mean there might be some change? Because everything, in my view, is quite messed-up. Average people and middle-income people are being harmed.”

As in the mid-1940s, many Canadians, especially younger people and newcomers, are desperate for solutions to this housing crisis, and want to see Ottawa adopt a wartime campaign adapted for the twenty-first century.

Housing Numbers Crunch

As of mid-1945, Canada had a population of eleven million, about a million of whom had served during the Second World War and would soon be decommissioned. As these numbers show, after almost a decade and a half of economic stagnation and wartime rationing, the housing shortage had reached crisis proportions.

45,000

The shortfall of housing units across Canada between 1941 and 1945.

620,000

Number of Canadians discharged between June 1945 and June 1946.

31,192

Rental dwellings completed by Wartime Housing Ltd. between 1941 and 1947.

29,452

Number of WHL homes sold off by the CMHC as of 1952, for a windfall of $110.5 million.

66%

Proportion of houses financed by the Veterans’ Land Act that were owner-built in 1949.

48,657

Number of houses completed between 1945 and 1949 using National Housing Act financing and lending programs administered by the CMHC.

More about Post-war housing

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement