Roots: First Steps for Family Historians

Getting started in family history can be overwhelming. There’s so much you don’t know, so many ancestors you could research. How do you avoid paralysis by analysis? Conversely, how do you resist the temptation to ride madly off in all directions?

In this and a subsequent column, I’ll describe one simple-to-follow methodology. But before we get started, I have one important question: Are you sure family history research is for you? To put this query in context, let me ask some others.

Do you have the patience to research properly? Will you give up if you don’t hit pay dirt in the first twenty minutes? Will you stubbornly defend time-honoured family stories in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary? Will you be reckless in jumping to exciting conclusions in the absence of persuasive evidence? If you answer yes to any of these questions, another pastime might be better for you.

Even if you’re a born researcher by temperament, do you have the composure and resilience to withstand the shock of unwelcome discoveries about your forebears? What if you learned that grandma had had a teenage “accident,” that a direct ancestor was a slave owner, or that a parent or sibling — or even you yourself — had been adopted? With these caveats in mind, how do you start?

I’m going to propose two steps you can undertake now. You’ll be assessing your present state of knowledge of your family’s history.

Next time, we’ll see how you can start confirming, refuting and building upon this base.

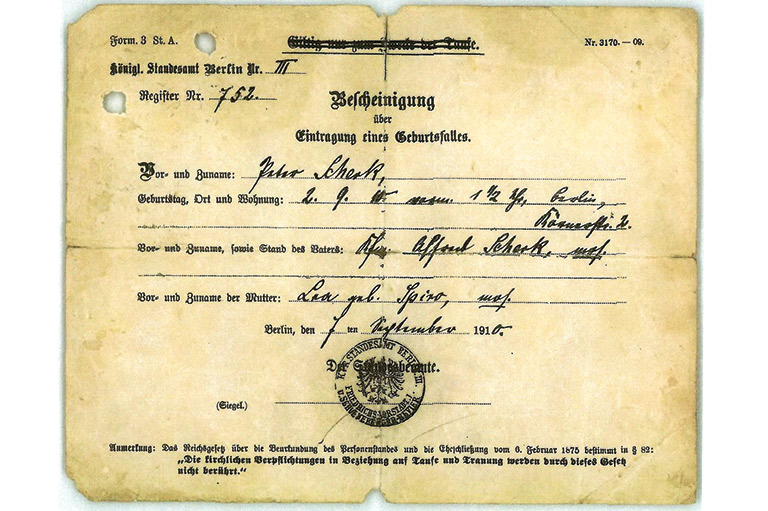

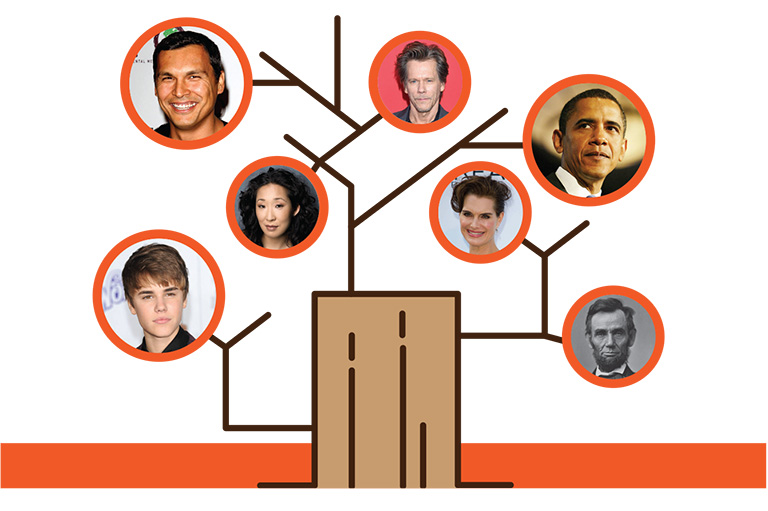

First, google and download a free “ancestry chart” template. A quick online search reveals many versions to choose from. Fill in as much of this form as you can from memory and with whatever documents you have at hand. Use a pencil, as this chart is very much a work in progress.

Advertisement

Starting with yourself, enter full names of your family members as far back as you can go, with dates and places of births, marriages, and deaths. Record doubtful memories, estimates, date ranges, alternate spellings, contradictory facts, even rumours. Don’t be concerned about accuracy at this stage.

Contemplating this outline of your immediate ancestry, you should next choose one of your four grandparents for closer scrutiny. Don’t go for the extremes, such as someone whose origins are a complete mystery or, conversely, a grandparent whose life has already been studied to death. Again, working from your memory of family lore and from information in documents in your possession, prepare a list of the key events and activities in this grandparent’s life. You’ll do an even better job if you consult with other family members at this stage.

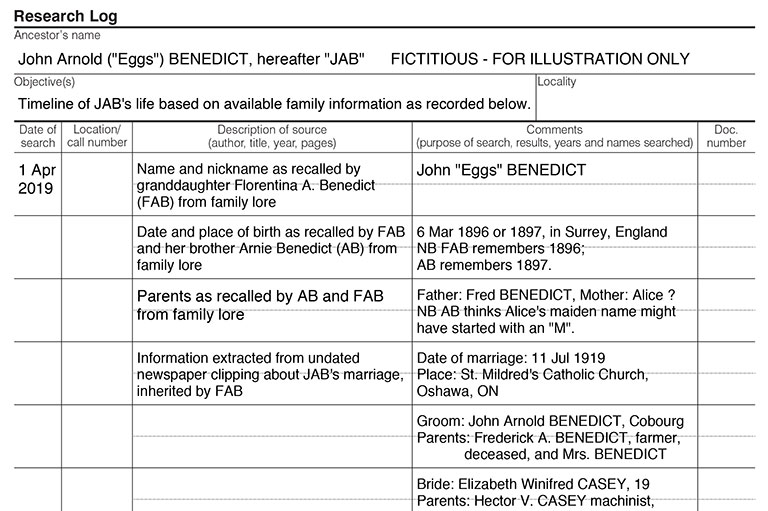

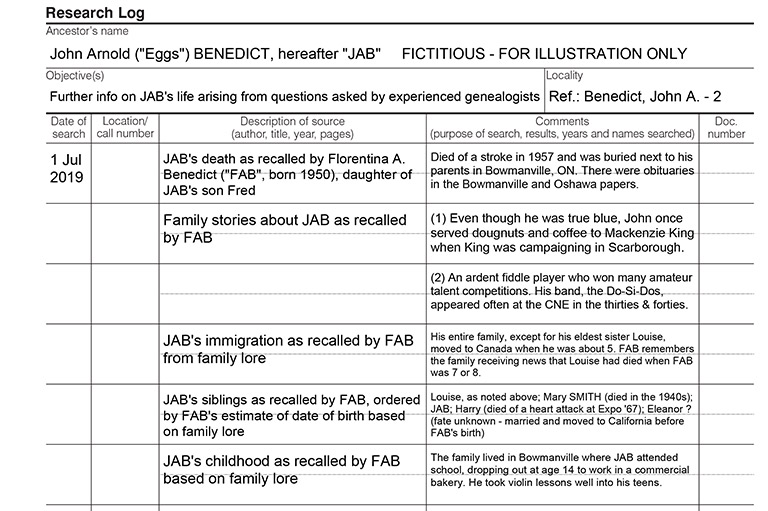

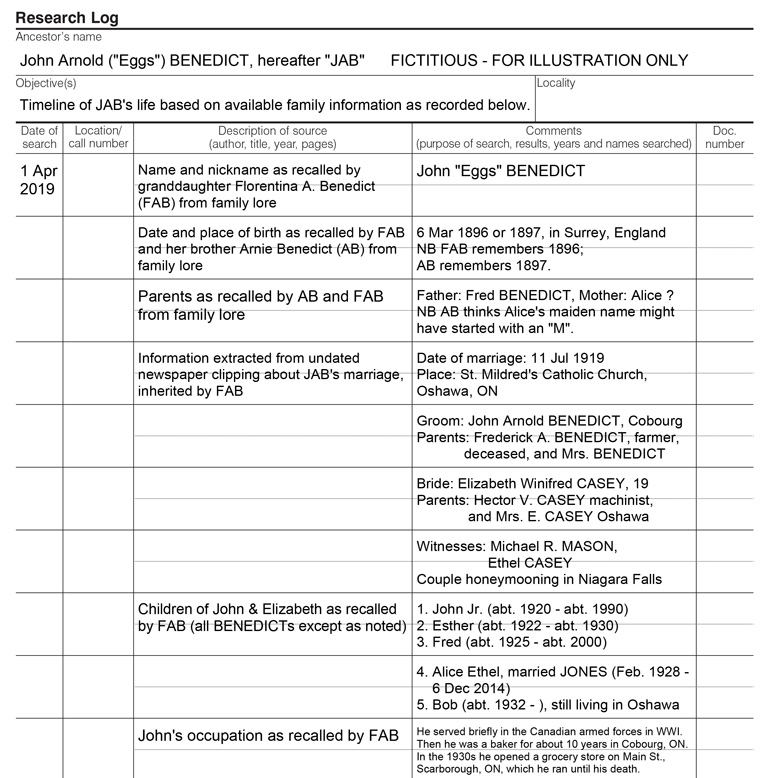

To illustrate, see the accompanying fictitious example for an imaginary grandparent named John “Eggs” Benedict. I used a fillable research log downloaded from FamilySearch.org. You could do the same, or you could emulate it either on a written page or a computer screen. Can you spot aspects of John Benedict’s life where I probably did an inadequate job of “remembering” him?

Your mission, should you decide to accept it, is to scour your memory and all family documents for every shred of information about the grandparent you’ve decided to research. How well can you do? We’ll see next time.

Family history step-by-step

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Wouldn’t your magazines like to slip into something more comfortable?

Preserve your collection of back issues with this magazine slipcase beautifully wrapped in burgundy vellum with gold foil stamp on the front and spine. Holds twelve issues.