Roots: Going Off Script

What’s the name of the person recorded in these two entries from nineteenth-century Canadian censuses?

I love this puzzler, which was recently posted on the Ontario Ancestors Facebook page by Karla Buckborough, CEO of the Cavan Monaghan Public Libraries located southwest of Peterborough, Ontario.

It illustrates almost all the common problems in deciphering handwritten documents — indifferent penmanship, inconsistent spelling, archaic words, extraneous markings, and, as with many images viewed online, antiquated digitization and unconvincing authorized transcriptions.

Advertisement

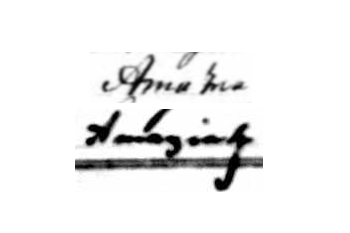

At least the names had not faded away to nothingness, as in this example.

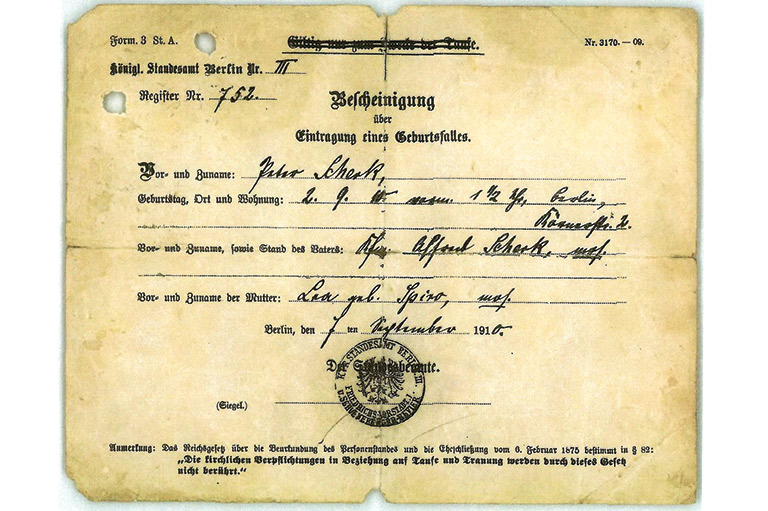

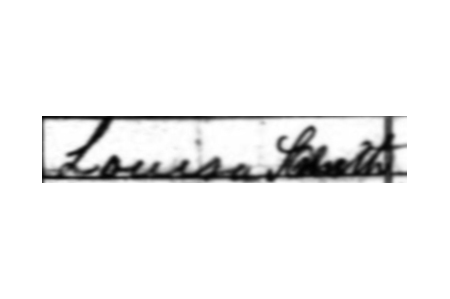

Family historians encounter similar problems all the time. I recently had occasion to study all people named Schuth in nineteenth-century English census enumerations. I concluded that there were more Smiths incorrectly identified as Schuth than there were Schuths correctly transcribed. In the following case, Louisa “Schuth” was preceded in the enumeration by five other members of the same household who were clearly named and correctly transcribed as Smith. Go figure!

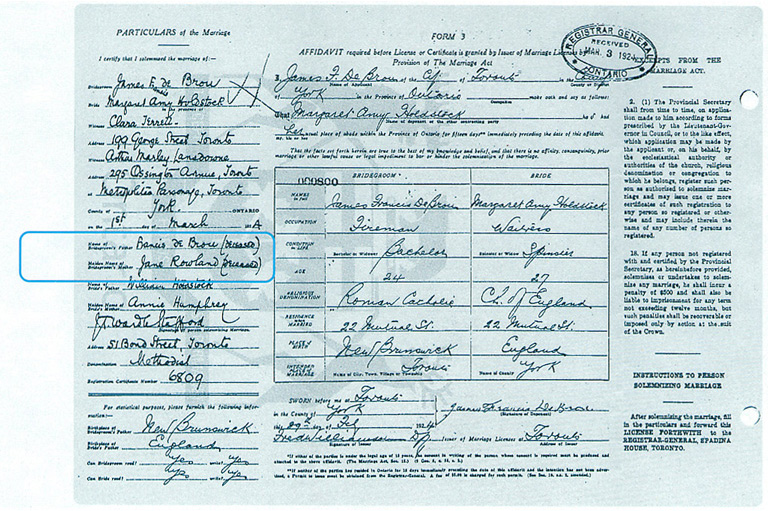

Much depends on who did the recording. Everyday people and official registrars typically occupy opposite ends of the legibility spectrum, with lawyers, priests, and enumerators somewhere in the middle but unpredictably so.

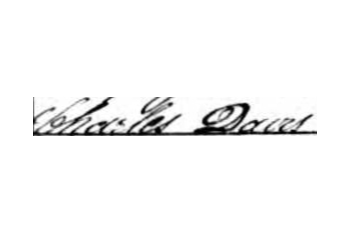

Bad penmanship or slapdash transcribing can be a bother even when you know precisely whom you’re looking for. Below is the name of one of my ancestors, a Davis indexed as “Daerr.” No amount of searching the database for Davis would find him.

Enough whining. How do we overcome these problems?

Most people’s natural tendency is to enlarge the image of indecipherable text by an order of magnitude in the hope that size will confer legibility.

That won’t achieve much beyond the point that easy words in a document can be read comfortably.

Playing around with settings such as brightness and contrast may help.

For me, flipping an image from positive to negative, or vice versa, sometimes jolts my brain into seeing things differently. Your best bet, though, is to work from the known to the unknown.

Find words in the document that you can identify with near certainty, such as dates or familiar names. Study how the scribe constructed various letters and letter combinations.

Can you find similar shapes in the illegible text? Can you exclude letters because the scribe has a distinctive way of writing them? Work methodically through the problem text.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

If you’re thorough, you will eventually arrive at a conjecture or a small set of possibilities that are consistent with all the other writing in the same hand within the same document.

To return to our puzzler, the official transcribers of the two images suggested that the names are Amaza and Annaziak, respectively — neither of them probable-sounding for an Irish-Canadian lad of the era.

Using the letter-by-letter technique described above, I conjectured Amazia and Amaziah. (Note that I discounted the vertical squiggle at the end of the second example as an extraneous mark.)

Another researcher, meanwhile, had pointed out that Amaziah was a Biblical name. A third investigator had found the death record of an Amaziah with the same surname, and, while he was clearly not the same person, it seems he may have been a relative. As I write, the matter is not yet settled, but the case for Amaziah is strengthening.

How do you know when you’re right? The gold standard is to find the conjectured transcription unmistakably present in other records.

This will usually entail whole-family research, for instance by tracking known and more readily identifiable relatives, whether parents, siblings, a spouse, or children, in the hope of serendipitously stumbling across the mystery person.

By the way, whole-family research is also the best method for finding known people whose names were muddled. My improbable “Daerr” ancestor was eventually found in a household with a grandmother and aunts.

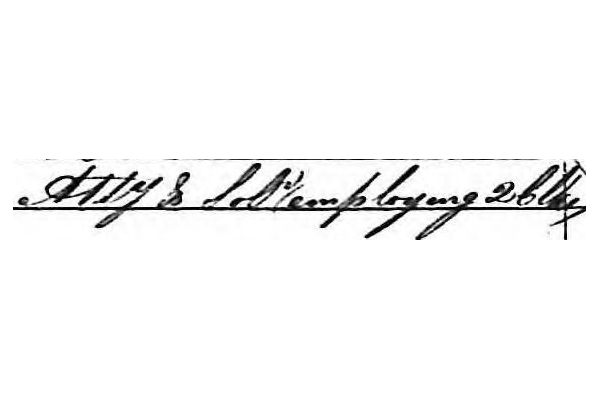

Not all failed attempts at deciphering sloppy penmanship are irritating. I was amused to find this transcribed occupation for someone I was recently researching: “Arty & self employing 2 boys 1 woman.” Huh?

Closer inspection revealed that a fair reading was: “Att[orne]y & Sol[icito]r employing 2 Cl[er]ks.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement