Roots: Final Steps for Family Historians

Advertisement

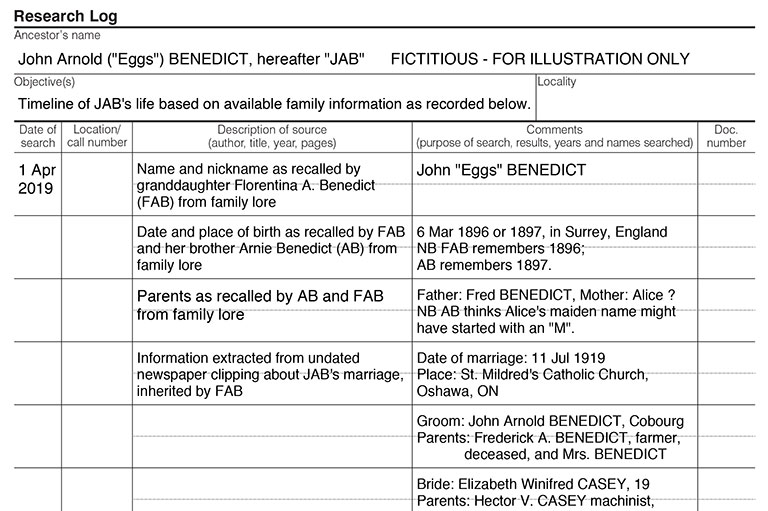

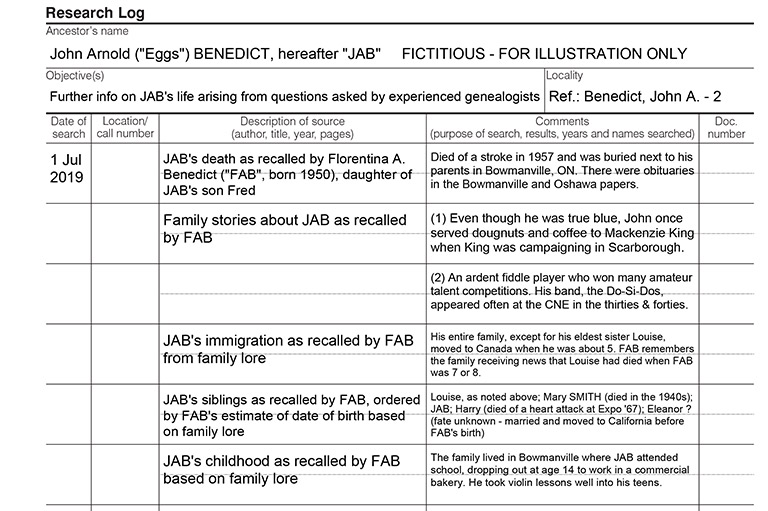

In the first two parts of this series, we’ve seen how essential it is to extract as much lore as possible from family sources. It’s now time to confirm what we think we know, fill in the blanks, and resolve the inevitable discrepancies.

In the case of our fictitious researcher Florentina A. Benedict (FAB) and her grandfather John “Eggs” Benedict, here are recommended next steps: Apply the same principles to your research.

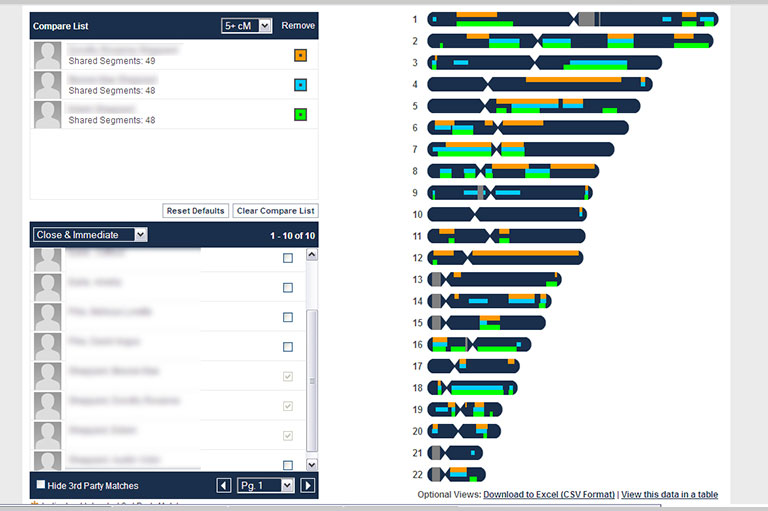

- FAB’s elderly Uncle Bob is still living, and she should go see him as soon as possible, taking notes or recording him if he’s amenable. Is he willing to take a DNA test? Once he’s gone, his DNA is too. Search “family history interview questions” online for suggestions to guide the conversation with your relative.

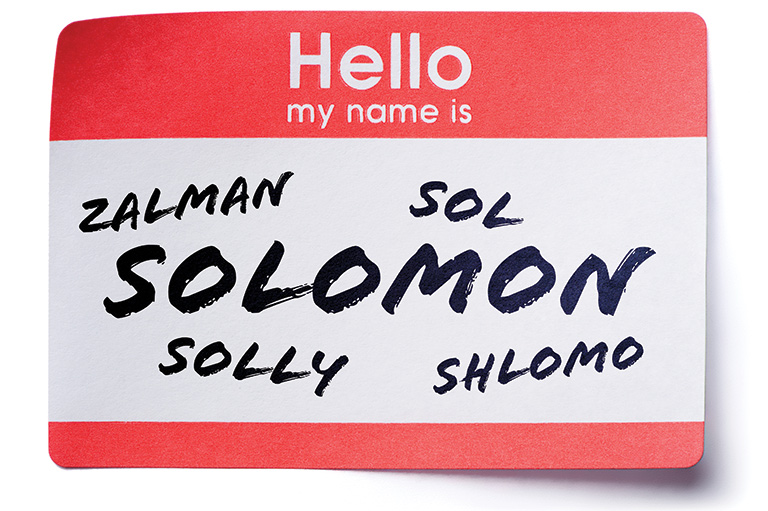

- FAB should confirm the basics of John’s life, as you should with the grandparent you’ve chosen to research, by seeking his birth record to establish particulars of name, date, place, and parentage. Similarly, she should find the registrations of his marriage and death. With John, his death falls within the closure period mandated by privacy legislation, but no such regulations apply to memorials or published obituaries. Censuses, church records, probate documents, and land and military records are other excellent sources.

- FAB should start a research log for each separate line of inquiry, record her sources, and remember that a negative finding should still be noted. (When you start out keep detailed records, unless you are fond of replicating your research!)

- Okay, Okay, I hear you protesting. How do I find these records you’re suggesting? There are many excellent books, courses, websites, webinars, and YouTube videos that deal with family history research — seek them out as time permits. In a pinch though, you can’t beat Google. Just search for the location of an event in combination with a short phrase describing the information needed. Here are several examples that would be helpful to FAB: “England birth records,” “Ontario marriage records,” “Canada military records.” Expect to find every permutation of online availability and accessibility. If the records are closed for a fixed period or indefinitely, search online to see what records family historians use instead.

- As you begin to confirm information from family sources, start organizing your raw findings systematically. For this, search online for “family group record template.” You will find many excellent and free examples. Eventually you’ll want to complete family group records for every couple (and their children) on your ancestry chart.

Don’t be shy in seeking free advice from libraries with specialists in local and family history, from Family History Centres run by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) — you won’t be proselytized — and from the volunteers of the genealogical societies operating where your ancestors lived and where their records are stored.

Don’t know how to find them? Try searching “[your community] library family history,” “[your province] LDS family history centres,” or “[your community] genealogical society.”

Fairly soon you’ll want to move from paper to digital record-keeping. It’s a convenience to use genealogical software to store your records, sources, and images, as well as to generate ancestry charts, research logs, and family group records at your command. Perhaps embark on this as you expand your research to encompass all lines of your family, not just one grandparent.

At the outset, though, you don’t need to complicate the ABCs of genealogical research with the added burden of a technological learning curve.

Happy hunting!

Family history step-by-step

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Wouldn’t your magazines like to slip into something more comfortable?

Preserve your collection of back issues with this magazine slipcase beautifully wrapped in burgundy vellum with gold foil stamp on the front and spine. Holds twelve issues.