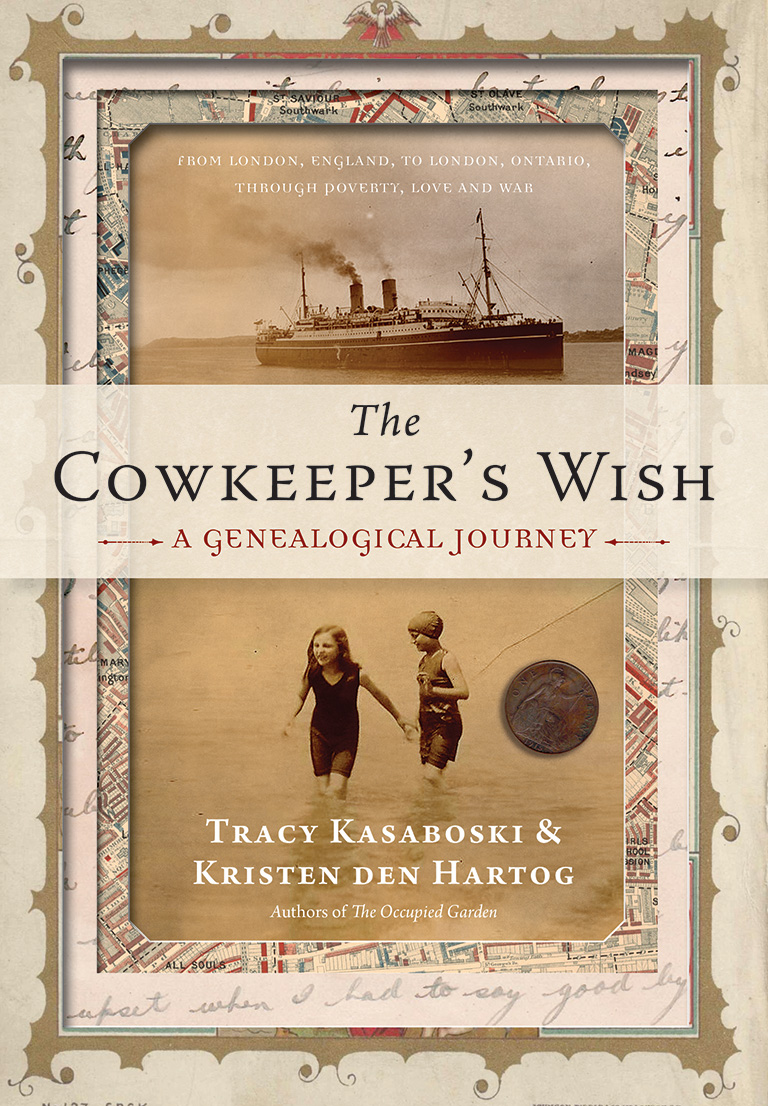

The Cowkeeper’s Wish

The Cowkeeper’s Wish: A Genealogical Journey

by Tracy Kasaboski and Kristen den Hartog

Douglas and McIntyre, 447 pages, $32.95

In its first few paragraphs, The Cowkeeper’s Wish dispels any fear that we’re in for four hundred-plus pages of chronological minutiae masquerading as family history. Early in the book’s prologue, authors Tracy Kasaboski and Kristen den Hartog set out their credo: “As the searcher makes her journey into the past, tracing yet another generation or growing her tree by a branch, it may occur to her that what she has gathered are clues, and that the part that matters, the story, has yet to be told.”

Yes, yes, yes! Of course, in genealogical research it’s necessary to do a thorough and accurate job with names, dates, and places. (After all, if you make a mistake, you’ll unwittingly research a stranger’s ancestors, not your own.) Yet does it really matter if your third greatgrandfather was a Willy or a Sam? Such detail only counts when we learn his achievements and disappointments, his loves and losses, how he lived his life.

Already the authors of a well-received family memoir, sisters Kasaboski and den Hartog meet this challenge head-on. They present a complex multi-generational saga starting in the early 1840s with a poor Welsh dairyman who sought to better his lot in life by relocating (on foot) to the metropolis with his wife-to-be and his cows.Soon their burgeoning family, not to mention the livestock, was settled in the meanest streets of the largest city in the world at that time, the London of Charles Dickens’ novels and, later, of Charles Booth’s poverty maps.

Through the experiences of family members, we encounter a victim of Jack the Ripper, the Salvation Army in its formative years, Charlie Chaplin and his mother, the final moments of the Titanic, deadly U-boat attacks in the North Sea, and Guy Lombardo as a teenage musician in the other London, Canada’s own, where the story eventually takes us in the aftermath of the Great War.

On their website, the authors refer to this tale as a “family/social history,” and they take every opportunity to allow “the broader scope of world history … to permeate the tale.” We suffer through London’s lung-searing fogs; we encounter the family’s many shockingly early deaths and humiliating detentions in the workhouse and the asylum; we hobnob with royalty (who knew Edward VII was such a fine diplomat?); and we experience the prejudice against poor Londoners in the Canada of a century ago.

Throughout, the prose is graceful, the research meticulous. As a bonus, the book is nicely designed, printed on high-quality stock. The text is supported by thirty photos, most of them from the family’s collection, and one would have welcomed even more.

I do have a criticism: This is a book that needs a proper bibliography and an index, but it has neither. The endnotes are profuse — about one per page on average — but they cannot conveniently fulfill these other roles.

The absence of an index is particularly galling for readers with anything less than a perfect memory. One of the book’s many strengths is a huge supporting cast of family friends and minor public figures, all admirably introduced to the reader when they first appear. How frustrating when a character returns later in the narrative and you don’t remember who this is. To mitigate what was no doubt a budgetary decision, might the authors provide an index on their informative website, if only for names and places? (They might also take this opportunity to present even more photos from their albums.)

The lack of a bibliography or an index should not diminish one’s appreciation for the meticulous research on a stupendous scale that underlies the tale. Going far beyond the usual genealogical tool kit (church and civil records, censuses, and the like), Kasaboski and den Hartog delve into the parish chest, minutes of regulatory bodies, registers of various institutions, police and newspaper reports, and the findings of two Royal Commissions. They are also blessed with extensive family lore, including the late-in-life recollections of one of the story’s central figures.

Even so, telling a story requires more than great facts. To research is to move backward in time and to answer the questions who, where, and when. Narration is forward-looking and brings new considerations into play: how and why? We often can’t know for sure, and we need a novelistic sensibility, so richly visible here, to interpret circumstantial evidence and to express nuance.

There was one act in this saga that required no parsing for motivation: “To make my home” was the unambiguous declaration by the Welsh dairyman’s great-grandchildren in support of their Canadian immigration. And it was thus, as for so many others, that the authors’ forebears ultimately escaped generations of first rural and then urban poverty, at long last fulfilling the cowkeeper’s wish.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement