They Made the House

When lacrosse teams take the field at the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, the players for the Haudenosaunee Confederacy hope to make history. If the International Olympic Committee allows them to compete, they’ll be part of the first-ever Olympic team representing an Indigenous nation — and they’ll set a precedent that could allow other Indigenous peoples to field Olympic teams in the future.

“Everyone agrees that we belong there, but on the Olympic side of it, if they allow us to compete as our own nation, what does that mean for other Native tribes around the world?” said Darcy Powless, general manager of the Haudenosaunee Nationals lacrosse team. “Skill-wise and talentwise we deserve to be there, it’s just all the political stuff. We hope they recognize us and allow us to play our game on our territory.”

Ranked among the top three lacrosse teams in the world, the Haudenosaunee Nationals broke through a previous barrier in 1990, when World Lacrosse admitted them into international competition after years of denying them entry on the basis that the Haudenosaunee Confederacy was not a sovereign nation. Eventually, federation officials had to relent: After all, lacrosse was invented by the Haudenosaunee — and, like lacrosse, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy is many hundreds of years old.

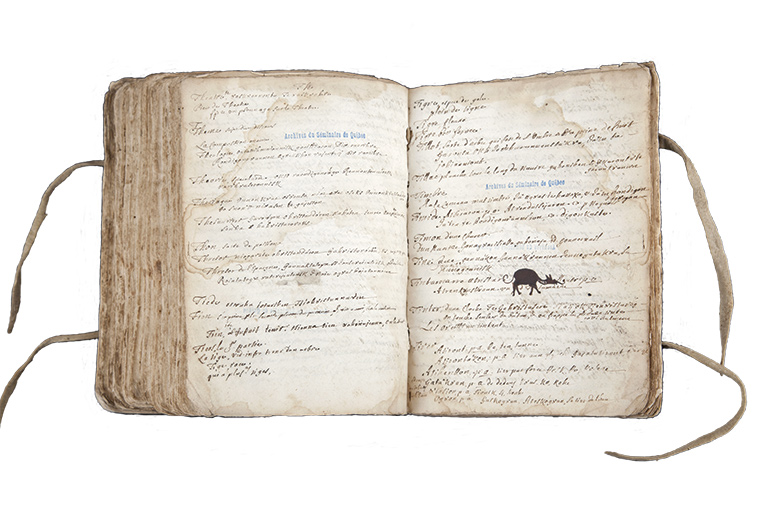

“We are all one house, we five Iroquois Nations; we keep one fire, and we have always lived under one roof,” a Haudenosaunee chief told the Jesuit Father François le Mercier in 1654. Le Mercier, who called the Haudenosaunee by the French name “Iroquois,” went on to note in the Jesuit Relations: “Truly, these five Iroquois Nations have forever called themselves in their own language … ‘Hotinnonchiendi,’ which means ‘the complete house,’ as though they were but one family.”

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy brought together five founding nations — the Mohawk, Cayuga, Seneca, Oneida, and Onondaga — along with the Tuscarora, who joined later, under an overarching Grand Council to decide important matters of common concern. The founding date of the Confederacy remains a matter of debate among scholars, who have sought to pin it down by cross-referencing archaeological evidence and astronomical data with events recounted in oral history, notably a period of internecine warfare and a solar eclipse that immediately preceded the decision of the Seneca to join the league.

For the Haudenosaunee, however, there is a fluidity to the Confederacy’s origin, and the exact dates are less important than the story, which has been passed down orally for hundreds of years. Although there are many variations and interpretations of the origin story, they all begin with the Peacemaker.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

According to the story, the Peacemaker was born in a community on the north shore of Lake Ontario, near present-day Deseronto, Ontario. His destiny to be the Peacemaker was foretold to his grandmother in a dream that predicted he would bring good news of peace and power. In some stories, his mother was human, while his father was a non-human being.

“He was sort of supernatural — I don’t want to say a divine entity or Jesus, but I guess that’s a close approximation of how he is regarded,” said Rick Monture, a member of the Mohawk nation, Turtle clan, from Six Nations of the Grand River Territory and an associate professor in the Department of English & Cultural Studies and the Indigenous Studies Department at McMaster University in Hamilton.

At the time of the Peacemaker’s birth, the Mohawk, Cayuga, Seneca, Oneida, and Onondaga shared a common culture, spoke one language that spanned various regional and national dialects, and occupied well-defined territories from the Genessee River in the west, through the Finger Lakes, to the Hudson River in the east. Yet it was a dark time in Haudenosaunee history, when distrust and violence flourished between nations, resulting in war, revenge killings, and kidnappings.

The Peacemaker grew up to become the leader of his village, but he knew his destiny was to bring the message of peace to the Haudenosaunee people on the south side of Lake Ontario. So he set out on his mission, asking his grandmother and mother to help him put his canoe in the water. It is said that although his canoe was made out of stone it floated — a sign that he was a special being whose words should be heeded.

The Peacemaker travelled among the five warring nations — Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, and Onondaga — telling them that if they committed to peace the others would, too. On his travels he also picked up Hiawatha, who in varying accounts is either the Peacemaker’s right-hand man or his spokesperson. In some versions, Hiawatha is a cannibal whom the Peacemaker convinces to leave his man-eating ways. Their partnership foreshadows how modern-day governance is structured, with many of the important roles held in pairs, such as the chief and sub-chief, or the faith keepers — one male and one female — who must promote the spirituality of the clan and serve as spiritual advisors. Djigonsasa, a Seneca woman, was the first individual to believe in the Peacemaker, and her belief inspired the Peacemaker to give women an important role in the Confederacy.

The first people to accept the message of peace were the Mohawks, or Kanien’kehá:ka, meaning People of the Flint. A representative body from that nation went on to the village of the Oneida, or Onyoteaká, meaning People of the Standing Stone, who also accepted the peace. Then the Peacemaker and Hiawatha travelled onward to the Onondaga, or Ononda’gega, meaning People of the Hills. Although the community wanted to join the peace, they had a terrifying chief who refused to renounce violence.

Failing to convert the Onondaga chief, the Peacemaker and Hiawatha moved on to the Cayuga, or Gayogohó:no, meaning People of the Great Swamp. The Cayuga accepted, and Hiawatha and the Peacemaker travelled westward again to the Seneca, or Onodowa’ga, meaning People of the Great Hill, the most populous of the five nations at that time. “They [the Seneca] were even more militarily minded than our people, because they were always defending their homelands in Western New York,” said Monture. They were often attacked by the surrounding Wendat, Susquehannock, and Algonquin nations.

According to Rick Hill, Beaver clan of the Tuscarora nation of the Haudenosaunee at Grand River and the founding coordinator of the Indigenous Knowledge Centre at Six Nations Polytechnic in Brantford, Ontario, the Seneca have the role of Keepers of the Western Door, a role negotiated for the warriors within the group to become the protectors of the Confederacy.

The story goes that, on the return of the Peacemaker and Hiawatha to the territory of the Onondaga, the Peacemaker taught the Mohawk and Oneida delegations a song of peace, which is still used today when a new chief is brought into the Confederacy. Recognizing the power of this group of people bringing a message of peace and a song, the leader of the Onondaga changed his mind, deciding to abandon his violent ways and to accept the peace. With all five nations in alliance, the Confederacy was officially established.

“When the Peacemaker brought everybody together, he said: ‘From here forward, you will be known as Haudenosaunee, meaning that we built this house,’” said Monture. “Each nation is a member of this longhouse, so we exist under one roof, and so, like any group of families in this longhouse, you have to work together to get along and keep it strong, safe, and secure.”

Advertisement

The stories of the Seneca, passed down for generations, relate that a total solar eclipse occurred in the days just before they joined the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. This rare event has prompted scholars to suggest various dates for the formation of the Confederacy based on astronomical calculations of historical solar eclipses. While some historians have proposed the years 1451 or 1536, University of Toledo American studies professor Barbara Mann and statistician Jerry Fields built a case for the much earlier date of 1142 CE in their essay “A Sign in the Sky: Dating the League of the Haudenosaunee.” In addition to the noted occurrence of a total solar eclipse visible over traditional Seneca territory on August 31 of that year, Mann and Fields pointed to archaeological evidence of palisaded villages built around that time — indicating a state of warfare between First Nations preceding the Peacemaker’s quest — and to records like François le Mercier’s note in the 1654 Jesuit Relations, which indicated that even in early colonial times the Confederacy was already an ancient institution.

“A lot of non-Native scholarship will say that the Confederacy’s not all that old, but our people say that it is,” said Monture. “If you look back into enough historical records, colonial officials were talking about the Confederacy, [saying that our people were telling them in the seventeen hundreds that it was several generations old, which would make it pre-contact.”

Monture added that, because Haudenosaunee people didn’t keep track of things in calendar years, the common expression to date events of the distant past would be “many generations before.” But he agreed that, looking at scientific evidence, a date of formation in the twelfth century is possible.

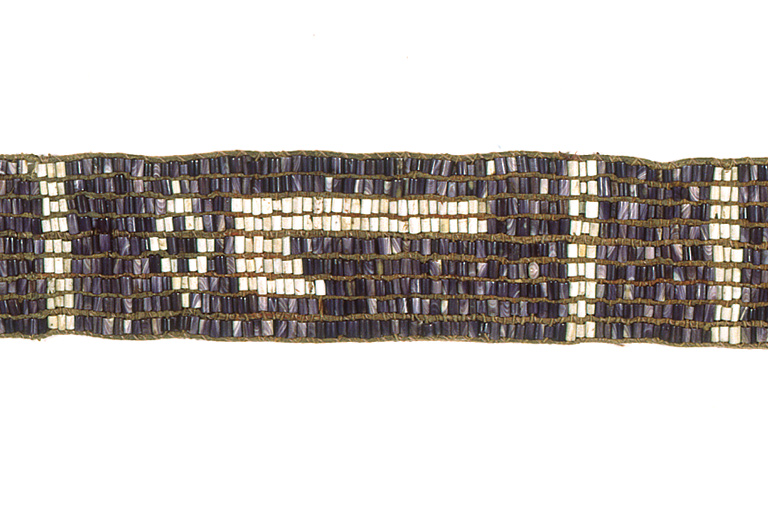

The founders of the Confederacy established an oral constitution, known as the Great Law, as well as a system of government. At the heart of the Great Law is the principle of peace that connected the five nations together. The law is an oral constitution that was recorded by Hiawatha in a wampum belt, the Haudenosaunee’s preferred method of preserving stories, laws, and traditions. Made of shells, the Hiawatha Belt is purple with two white squares on each side and the tree of peace in the middle, all connected by rows of white.

The tree of peace is a symbolic white pine that is said to have all of the nations’ weapons buried beneath it. The Peacemaker used the tree as a symbol of unity: The needles of a white pine tree grow in bundles of five, just as the Confederacy had five founding nations. White pine is an evergreen, symbolizing its vitality, and it rises above the rest of the trees in traditional Haudenosaunee territory. “It’s kind of like a beacon,” said Monture. He likened it to a church steeple or the Egyptian pyramids. “Humans want to look towards something that is closer to the heavens.”

“The Great Law is a series of lessons about how people transform their thinking, as a model,” said Hill. “The law is not like in European law, where it’s all codified.” Instead, it’s a series of values, rooted in a basic respect for all people’s rights, in democracy, and in using reason to ensure peace. These values should be applied to decision making and relationship building, with a focus on inclusion and collaboration. The Great Law doesn’t have police to enforce it or judges to rule on it.

Under the Great Law, a governing body known as the Grand Council was established with representatives of each Peacemaker, the Grand Council was tasked with deciding large and important issues that affected all five nations, like maintaining peace, ensuring the wellness of the people, and ensuring that future generations would be able to enjoy the world as they knew it. Smaller, more local matters were resolved within each nation itself. “This is about, how do we make sure we keep our sacred relationship to the earth and all of its forces alive?” said Hill.

The representatives sent to the Grand Council were chosen from within each nation according to a system of clans. Each nation was composed of family-based, matrilineal clans represented by animals, such as the wolf, beaver, and bear. The Peacemaker selected a woman from each clan as a clan mother, with the responsibility of choosing the chief or chiefs of that clan. The clan mothers also had the responsibility of unseating a chief, if need be. “The idea is that the women see a young man growing up and see who’s a natural leader, who’s generous and kind, and not boastful or greedy,” said Monture. “There’s a lot of power there, too.” In longhouses — originally the buildings where the Haudenosaunee lived, but now hubs where people gather for ceremonies and socials — and in the Confederacy today, women continue to hold this role, creating a balance of leadership among the men and women of the community.

In total, fifty chiefs were chosen as representatives to attend meetings of the Grand Council. The Council met on the territory of the Onondaga, the designated hosts and the keepers of the council fire. The Onondaga, Mohawk, and Seneca were known as the Elder Brothers, while the Cayuga and Oneida were called the Younger Brothers. Each proposal brought forward was first debated by the Mohawk and Seneca chiefs. Once they reached an agreement, their decision was then passed on to the chiefs of the Cayuga and Oneida for discussion. When those four nations all agreed, the final decision was submitted to the chiefs of the Onondaga for ratification.

The chiefs of each clan were expected to act in the best interests of their people and to bring their peoples’ interests and concerns forward at the council. In that sense, it was a bottom-up model of decision making. “It’s not for the leaders to solve our problems. But if the leaders help us to solve our problems, there’s a big difference,” said Hill. “You can command from above like in the Western model — the Pope makes a declaration, the King makes a declaration — but in our case it’s getting people to use their mind to resolve their differences, and that’s a very significant contribution to governance in my mind.”

That type of thinking about coexisting, an extension of the principles of the Great Law, is one of the Confederacy’s greatest successes, according to Hill.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The arrival of Europeans on the North American continent complicated the lives of the Haudenosaunee, drawing them into alliances and conflicts that revolved around trade and colonization and exacerbating long-standing animosities with other Indigenous peoples. Led by Samuel de Champlain, the founder of New France, the French entered into alliances with the Huron-Wendats, Algonquins, and Innu (Montagnais), all of whom were traditional enemies of the Haudenosaunee. In 1609 Champlain accompanied a party of Huron-Wendat, Algonquin, and Innu warriors in an attack on a fortified Mohawk settlement at Ticonderoga (in present-day upstate New York). According to historian David Hackett Fischer, this may have been the first time in North America that a European joined in a battle between two Indigenous foes. It was, however, far from the last.

“After the French arrived and started making war rather than peace, the Confederacy turned their eyes to the Dutch and then the English to say, let’s make peace,” said Hill. In 1613, representatives of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy met with Dutch settlers — who had begun trading and building forts along the Hudson River in present-day New York and New Jersey — to agree to the Two Row Wampum covenant. This covenant focused on respectful coexistence.

The wampum has a white background, with one row of purple beads that represents the Haudenosaunee people’s canoe, — carrying their traditions, way of life, and laws — and a second row of purple beads that symbolizes a Dutch ship, carrying the same things for the Dutch people. The separate and parallel lines tell a story of respecting one another’s paths, and they represent an agreement to share the lands and what they produce.

Said to have been originally imparted by the Peacemaker, the motif of the Two Row Wampum appeared again in agreements with the French, British, and Americans in the ensuing years. “The strategy that comes out of the Two Row Wampum, about how we’re going to coexist in this land, it was very keen insight,” said Hill. “Otherwise we would have been wiped out like many of the other [Indigenous] groups.”

The Five Nations became the Six Nations in 1722, when the Tuscarora nation was first acknowledged by Treaty council. Defeated in a war against British colonists, the Tuscarora had left North Carolina in 1712 and endured a decade-long exodus to reach upstate New York, where they joined the Haudenosaunee Confederacy as a member nation. While the Tuscarora came to “shelter themselves under the tree of peace,” said Hill, the Great Law was specific to the original five nations. The Tuscarora do not have representatives in the Grand Council. When they have an issue to discuss, it is voiced through the Cayuga.

The American Revolution that broke out in 1775 shattered the Confederacy’s unity. Initially the chiefs and clan mothers wanted the nations to remain neutral, but they faced increasing pressure from the British and from the American colonists to align themselves with one side or the other. Eventually, many of the Seneca, Cayuga, Mohawk, and Onondaga warriors fought for the British, while the Oneida and Tuscarora sided with the Americans. Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant became one of the most prominent fighters and Indigenous leaders on the British side.

“They broke the Great Law by spilling each other’s blood,” said Hill. “The Great Law is based upon consensus, but because of colonization and politics, economics, and religion, [the Confederacy] became split and no longer could become of one mind,” said Hill. “It’s not the fault of the Confederacy; it’s really the fault of the people whose individual wants outstepped our instructions about peace.”

After the Americans won the Revolutionary War, the British governor of the province of Quebec, Frederick Haldimand, granted a tract of land in the area that is now southern Ontario to the Mohawk and to “others of the Six Nations who have either lost their settlements within the territory of the American States or wish to retire from them to the British.” The tract, granted in 1784 to “his majesty’s faithful allies” covered approximately 3,844 square kilometres and was defined as the territory “upon the Banks of the River, commonly called Ouse or Grand River … Six Miles deep from each side of the river beginning at Lake Erie and extending in that proportion to the Head of said River, which Them and Their Posterity are to enjoy Forever.” Following Joseph Brant, many Haudenosaunee settled in the Haldimand Tract, where their community became known as the Six Nations of the Grand River.

Some twenty Mohawk families instead chose to settle on the Bay of Quinte on the north shore of Lake Ontario, where in 1793 Upper Canada Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, in the name of King George III, granted a deed to 375 square kilometres of land to “the Chiefs, Warriors, Women, and People of the said Six Nations and to and for the sole use and behoof of them and their Heirs forever.” Nevertheless, the land was overrun by Loyalist settlers in the early nineteenth century; the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte now retain approximately seventy-three square kilometres of their original land grant.

Mohawks also continued to live in settlements established by Jesuit missionaries in Kahnawake, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River opposite the island of Montreal, and in Akwesasne, on both sides of the St. Lawrence River near present-day Cornwall, Ontario, and St. Regis, New York. The Akwesasne Mohawk territory was severed in two by the border when the United States and Britain signed the Treaty of Paris in 1783 at the end of the American Revolution. The treaty placed the international border in the middle of the St. Lawrence River, without regard to the boundaries of existing First Nations settlements. This border was reconfirmed in the Treaty of Ghent that ended the War of 1812.

In the United States, much of the Haudenosaunee land was seized by the U.S. government and sold to settlers. The reservation land that the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, Tuscarora, and Mohawk managed to secure represented a small fraction of their traditional territories.

Advertisement

After settling in the Haldimand Tract lands, the Six Nations of the Grand River continued to govern themselves according to their traditional ways, with chiefs of each nation coming together in a governing council called the Haudenosaunee Confederacy of Chiefs Council (HCCC).

After Canadian Confederation in 1867, however, the Canadian government set in place laws and policies meant to extinguish Indigenous governments and practices and to assimilate Indigenous people into Canadian society. In the 1920s, the Canadian government moved to impose its laws and authority on the Haudenosaunee and built an RCMP post on the Haldimand Tract lands. In response, after failed discussions with the Canadian government, Cayuga Chief Deskaheh (Levi General) began a yearslong campaign to have the Six Nations of the Grand River recognized internationally as a sovereign nation.

“Great Britain and the Six Nations of the Iroquois … having been in open alliance for upwards of one hundred and twenty years immediately preceding the Peace of Paris of 1783, the British Crowns in succession promised the latter to protect them against encroachments and enemies making no exception whatever,” Deskaheh wrote in an appeal to the League of Nations in August 1923. Describing the Haudenosaunee’s alliance with the British during the American Revolution, and the loss of their lands after that war, he continued: “Thereupon, the Six Nations … at the invitation of the British Crown and under its express promise of protection, intended as security for their continued independence, moved across the Niagara and thereafter duly established themselves and their league in self-government upon the said Grand River lands, and they have ever since held the unceded remainder thereof as a separate and independent people, established there by sovereign right.”

In response to this “agitation” by “a great trouble-maker,” the deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, successfully lobbied Great Britain and Canada’s international allies to deny the Six Nations’ claim, arguing that the Haudenosaunee “are British subjects in the same manner as other natives or aborigines born within the territorial limits of the Empire.” At Scott’s instigation, in September 1924, the Canadian government stripped the HCCC of its authority and instead imposed an electoral system of government on the Six Nations of the Grand River. The new council, elected by adult men, had limited powers under the Indian Act, such as the maintenance of public roads and buildings — far from the full sovereign governance powers claimed by Deskaheh and the Haudenosaunee chiefs.

“The biggest failure is, we trusted our Treaty partners too much,” said Hill, adding that the people of the Confederacy no longer had the unity of mind required by the Great Law to resist these changes. “We thought their word was good, because the pledges they made would be honoured.… We are upholding these values that we were instructed to do, but the Europeans had a whole different set of values in the belly of their ship.”

Despite the Treaty promises, the property owned and occupied by the Six Nations of the Grand River was diminished over the years by leases, sales, expropriations, alterations, occupation by squatters, and boundary disagreements. The Haldimand Tract is now a heavily populated area of Ontario that includes the cities of Cambridge, Brantford, Kitchener, and Waterloo, as well as numerous smaller communities. The Six Nations of the Grand River reserve occupies 188 square kilometres, or about five per cent of the original tract.

Today, the Six Nations of the Grand River band is governed by the Six Nations Elected Council (SNEC), composed of a chief and twelve councillors. All adult members of the band are eligible to vote in council elections. The traditional HCCC continues to exist in parallel, composed of chiefs appointed by clan mothers both from within the Six Nations of the Grand River and from other Six Nations bands in Ontario, Quebec, and the United States. The existence of these two separate bodies is something that causes tension to this day.

“We still have a system of governance operated on precontact principles, because, when you look around, there’s very few traditional councils still in operation in North America,” said Hill. “We still have chiefs, we still have our ceremonies. Okay, our language is hanging by a thread, but we still exist as a sovereign people.”

The HCCC continues to make efforts to assert Haudenosaunee sovereignty. It issues Haudenosaunee passports for international travel, although not all countries accept the document as valid identification. In 2021, the HCCC declared a moratorium on any development of land within the Haldimand Tract without consent from the Haudenosaunee Development Institute, the branch of the HCCC that deals with land, environment, and resources. While it’s not clear whether developers, municipalities, and landowners will heed the moratorium declaration, the volunteer organization Protect the Tract is working to educate people along the Grand River — as well as those in the Six Nations community — about the moratorium and land stewardship.

Meanwhile, the Six Nations Elected Council has turned out not to be as tame as Duncan Campbell Scott might have hoped. In a case originally filed in 1995 — and that is expected to go to court late in 2024 after many procedural delays — the Six Nations of the Grand River band is suing the Ontario and federal governments for financial compensation for lands in the Haldimand Tract that they claim were illegally taken from them over the past 250 years.

“It’s for essentially [compensation] for their unlawful taking of the land and unlawful misappropriation of any money from any sales of the land,” said Lonny Bomberry, director of the Lands and Resources Department of the Six Nations of the Grand River.

In their defence, Canada and Ontario argue that the land was not illegally taken, but rather that the Six Nations people made a series of valid sales and surrenders of lands within the tract. Some lands were also affected by canals and roadways. Canada and Ontario both deny that they have been at fault in their dealings with the Six Nations. The HCCC unsuccessfully applied for intervenor status, arguing that the case should be settled not in court but in nation-to-nation negotiations between the HCCC and the Canadian government. The Six Nations of the Grand River successfully opposed the HCCC’s bid to intervene.

Bomberry said the band is not claiming a specific dollar figure — that will be up to the trial judge — but the final settlement might include access to ongoing revenue streams such as resource extraction royalties and a percentage of property taxes or land-transfer taxes.

“We want to make sure that we have a continual income from the Haldimand Tract, indefinitely, forever,” said Bomberry. “Because that land was given to us, for Six Nations posterity to enjoy forever.”

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement