Fighting for Recognition

In the Algonquin Anishinaabeg tradition dibaajimowinan, or personal storytelling, is valued as a legitimate method of gaining and conveying knowledge. Dibaajimowinan is “wholistic” in that it values knowledge that is more than rational: it is emotional and spiritual too.

For me, most days, and especially Remembrance Day, are a bundle of contradictions in that my lived experience is laden with the genocide of colonial Canada — both historically and in a contemporary sense.

The Algonquin Anishinaabeg is a nation of people who straddle what is now called the Ottawa River watershed. Through processes of colonization we are now divided into provinces and by language, law, and religion. We were denied a treaty during the historic treaty process, and Canada’s Parliament squats on our land.

My great-grandfather Joseph Gagnon served in the First World War (1914–18). On September 12, 1910, in Eganville, Ontario, Joseph married Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe Annie Jane Menesse, the daughter of Mary Ann Bannerman and the adopted daughter of Frank Menesse. Joseph and Annie Jane were members of the Golden Lake Indian Reserve, now called Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, raising their five children: Viola, Cecelia, Gordon, Kenneth, and Steve. Viola, their first child, was my grandmother.

Through archival research I gained a copy of Joseph’s attestation papers that are dated May 12, 1916. His last name is spelled “Gagnon,” and his birthdate was recorded as April 7, 1890, making him twenty-six years old at the time of his enlistment. He was recorded as 5 feet 7.25 inches tall; he had brown eyes and brown hair, with a medium complexion, and was listed as a Roman Catholic.

Joseph enlisted in the 207th Battalion and then transferred to the 2nd Battalion; he served in Canada, England, and France. I learned that his port of embarkation out of Canada was Halifax, and he left on my grandmother Viola’s sixth birthday — May 28, 1917.

His port of disembarkation was Liverpool, England, on June 10, 1917, and he was demobilized on January 24, 1919, remaining a private, service number 246266, for the duration of the war.

According to the record, Joseph received the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. Family oral history, though, informs me that he may also have received the Military Medal. I have never seen these medals, and I am not sure where they ended up. The feelings that the military records and the oral tradition evoke — of a dutiful, decorated soldier — are real enough for me.

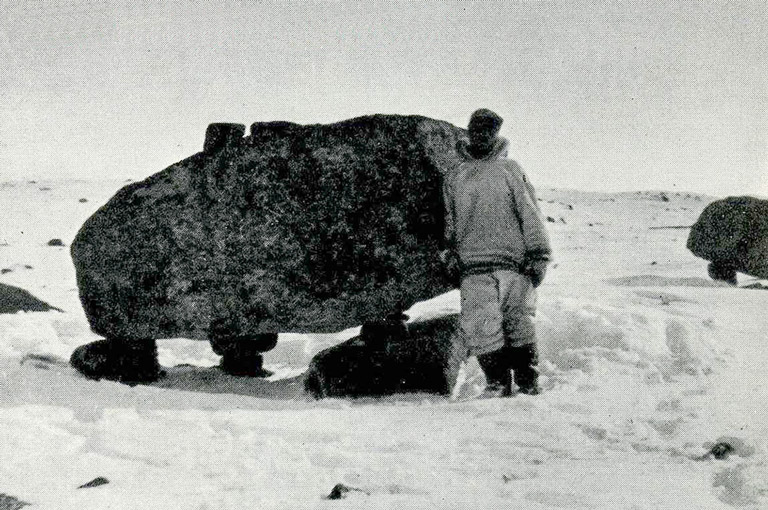

After the war ended Joseph returned to his family and home community, the Golden Lake Indian Reserve. From my family oral history I have learned that shortly after, in the 1920s, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police escorted him and his family out of their community, because his Indigenous identity was borne by his mother’s ancestral line rather than his father’s.

His wife Annie Jane’s indigeneity was irrelevant because women, according to British law, were mere appendages of their fathers and husbands. Apparently this practice was commonly imposed on Indigenous veterans and their families. When they came home from serving as the British Crown’s loyal allies, some lost all their treaty rights as Indigenous people.

While the Algonquin Anishinaabeg are the traditional Indigenous landholders of the Ottawa River Valley, through colonial policies and laws many of us were, and remain, denied the right to pass on to our families our national identity and our rights as Indigenous people — such as the right to own land and resources and, via this, the right to live a good life (mino-pimadiziwin).

Rather, as historian J.R. Miller has shown in Sweet Promises: A Reader on Indian-White Relations in Canada and Lethal Legacy: Current Native Controversies in Canada, and historian J.S. Milloy has shown in his essay “The Early Indian Acts: Development Strategy and Constitutional Change,” we were stripped of our national identity, and many others were relegated to living in reserve communities until we could prove we met the British criteria of what it meant to be civilized.

The reason for this, explains R.A. Williams in Savage Anxieties: The Invention of Western Civilization, was that British Canada did not view the Algonquin as real people but rather as pre-human beings without legitimate identity, culture, or governance traditions, whereby we consequently also lacked a valid holding on the land.

In concrete terms, the legacy of these colonial policies and laws also manifests today in the intergenerational transfer of landholdings, in the form of what is, and what is not, willed to the children and grandchildren of settler families and Indigenous families. The short story is that many settler families continue to benefit from Indigenous land and the denial of land rights. In this way, settler Canadians, you should know that my great-grandfather went to war for your rights not mine.

When I reflect on this reality, I am saddened that Joseph Gagnon fought for a country that took so much away from his family — and from his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. As Indigenous people of this land, my ancestors deserved the right and the responsibility to care for their children and to provide for them mino-pimadiziwin.

This is my story. Learning, sharing, and remembering should not be this hard.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!