Connecting with the land

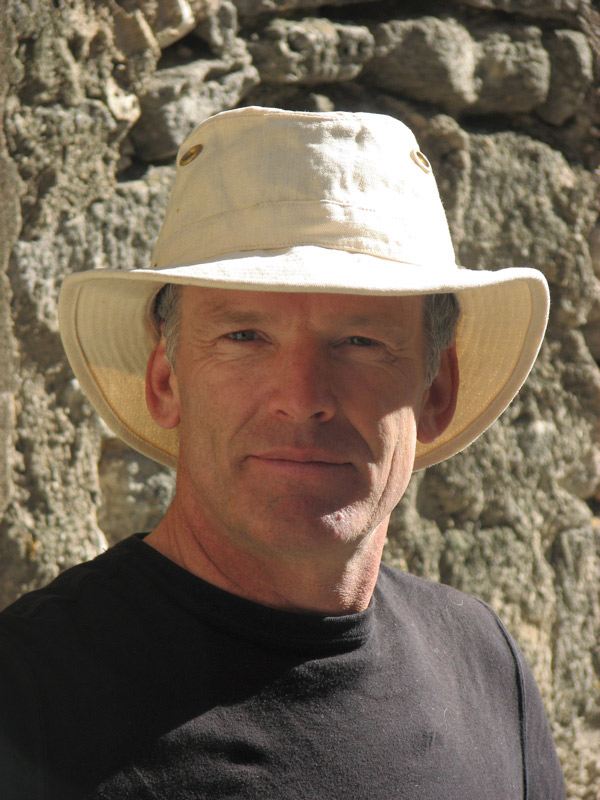

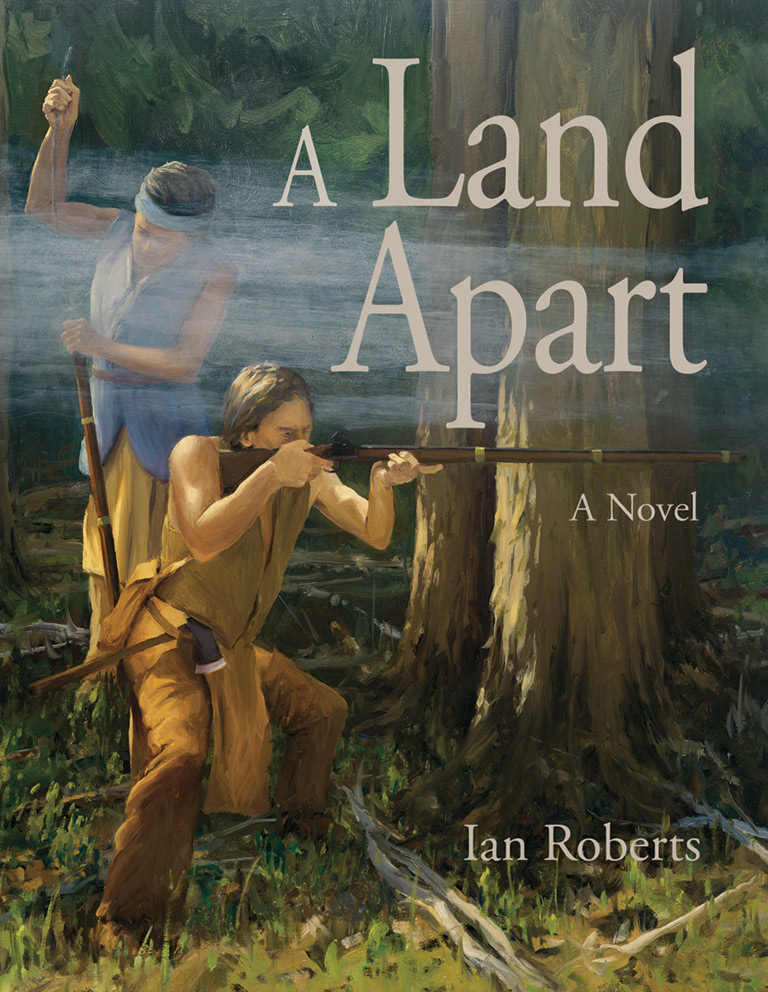

The historical novel A Land Apart, by Ian Roberts, draws from the experiences of trader and explorer Étienne Brûlé, who travelled to North America with Samuel de Champlain early in the seventeenth century and lived for most of two decades with the Wendat people. Canada’s History associate editor Phil Koch asked Roberts about his book.

Who was Étienne Brûlé, and why did you want him to be the central character in this particular story?

Étienne Brûlé was the first white man to go deep into the interior of Canada to live with Indigenous people. He was not part of an expedition. He went alone, in 1609. And he went hundreds of miles into the wilderness, from what is now Quebec to Georgian Bay, and lived there for decades.

He became the hero of the story because of the confluence of two things: When I was young I went on a lot of canoe trips in Ontario. I loved being out in the wilderness. A history teacher in grade eight somehow brought Brûlé to life for me, and his story — of someone who really made a home out there in the wilderness — just bounced around in my head until one day I had to tell it.

Brûlé appears to have been a strange trader, in that he worked not purely for profit, as well as an unusual explorer, producing neither notes nor maps. What do you think was his actual motivation for journeying and living with Indigenous peoples, and what might have been his expectations?

You are right in suggesting Brûlé was unusual as an explorer — he’s known to have gone as far west as Duluth and probably from there to the headwaters of the Mississippi — and as a trader.

I have a bumper sticker in my office that reads, “My church is the woods.” That is the motivation I give Brûlé for being out there. He naturally connected with and assimilated the Indigenous experience of the Great Spirit — not as a concept but as an expression of his existence in the woods. Now, I know I walk on thin ice here assuming that I understand Indigenous culture, but I do experience something tangibly spiritual when in the wilderness, and I projected that experience as Brûlé’s real motivation for being there.

Why did you use historical fiction to tell this story? And what sorts of differences from the historical record were involved your telling?

I started this whole project by writing a film script. It would, I think, make a great movie. I then turned the script into a novel. I did a lot of historical research, because you have to embed the fiction, movie, or novel in a plausible environment. But I always thought of telling Brûlé’s story as fiction, right from the start.

Since Brûlé kept no notes, we only have other people’s comments about him. You have to read between the lines a bit. The Jesuits didn’t like him because they felt that, rather than trying to elevate the Indigenous people to act like “civilized” Christians, he was damning himself by embracing an Indigenous lifestyle.

Champlain, his boss, had very specific things he wanted Brûlé to accomplish in terms of trade and alliances with the various tribes west of Quebec. Brûlé would disappear for two and three years at a time, so he wasn’t much use to Champlain. But there certainly are references, and you piece the parts together. He was the one out there. He was the hero, so I tended to lean on the positive I saw in him.

The whole plot line of getting guns — that would have been going on at that time, certainly. But I doubt that there was any moment where all the conflicting elements would have come to a head the way they do in the novel. The timeline gets condensed. And I don’t know of any reference to Brûlé trading guns — although they quickly became the most desired trade item.

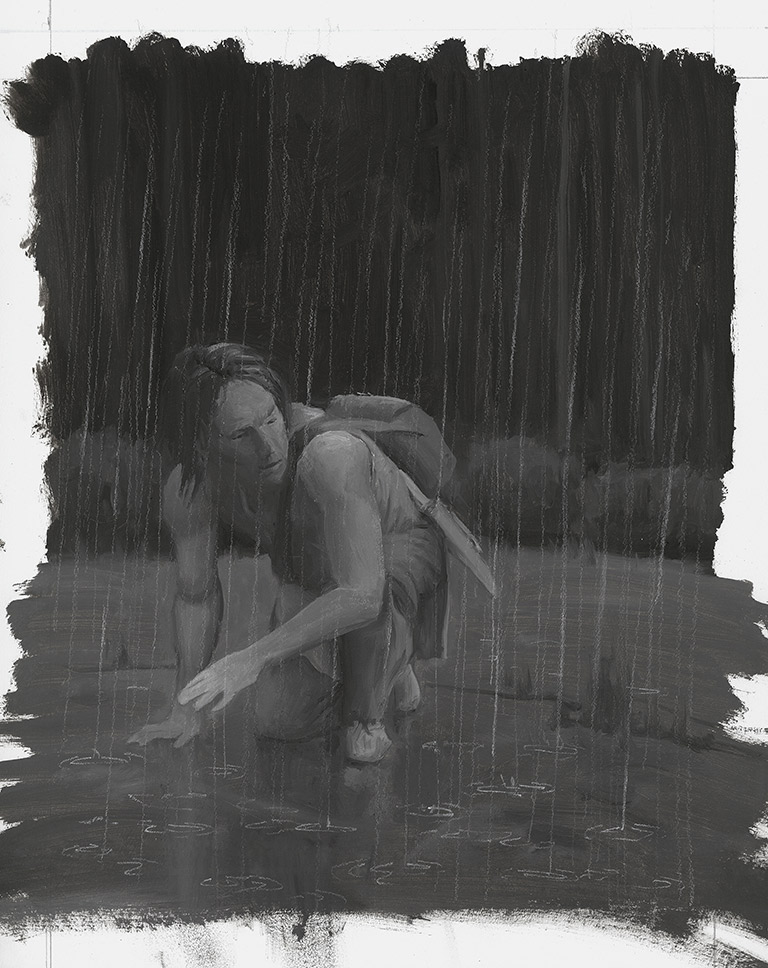

Your book is primarily a narrative, but it includes several of your own illustrations, particularly in an opening sequence. How did these illustrations come about, and did you consider including even more of them?

I’m a painter. I’ve been a full-time painter all my life, primarily a landscape painter. We don’t associate most landscape paintings with a strong narrative element. When getting close to finishing the novel, and with the land featuring as such a prominent character in the book, I thought I should give a visual expression to it. So I was fascinated with the idea of doing illustrations, many of them landscapes, that now had a distinct narrative role.

Most of the characters in the novel are grappling with the consequences of cultural encounters and the changes brought about by the interactions between Europeans and Indigenous peoples, including beliefs, technologies, and diseases carried from Europe. With novels being so intimate, how did you approach representing the sensibilities of the remote time and different cultures?

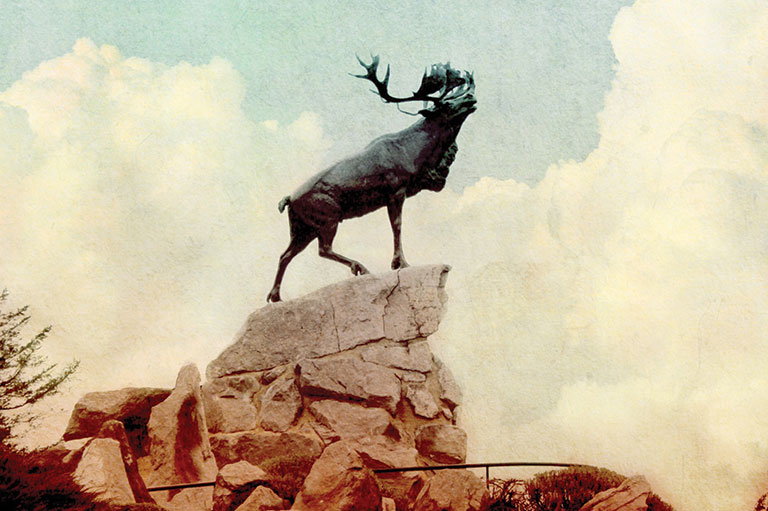

The overarching presence in the novel is the land. For the most part, the story takes place in a wilderness several hundred miles from the nearest European settlement. And Quebec was still a struggling settlement, not a town, in 1634.

For the Wendat and the Iroquois, of course, that wilderness was home. Trying to imagine their relationship to the land, or really the spiritual connection to nature and its cycles and forces, became central for me to establish, because all the Western characters are affected by the power and the living presence of the land. I mention in the afterword that I tried to give expression to Wendat spirituality with the deepest respect, however much I may have missed a true understanding and the details.

But the focus of my story was Brûlé, who lived out there for decades and must have embraced the Wendat culture deeply. So I had to create his relationship with this wilderness largely through the beliefs of his adopted people.

The wilderness strips the French characters of artifice, each in their own way. But the effects of the French were already tearing the fabric of the Wendat culture. Imagine making and using bone utensils all your life and then having a steel knife, or axe, or needle in your hand for the first time, and bolts of coloured cloth, and large metal kettles, or a musket. They had to have them. The disease came a little later.

As you’ve mentioned, the land itself is a key figure in your novel, including with respect to the characters’ different visions for and relationships with the land. In what sense are you suggesting the land is “apart,” and from what?

That is an interesting question, and I think it pivots on the idea that the wilderness offered a kind of paradise to Brûlé. At least you get a sense that that is what Brûlé has found out there. So the “apart” refers to leaving behind the terrible conflicts he witnessed as a boy in France, and leaving European culture in general, for the different values of an Indigenous life. It might not suit some people, but it certainly seems to have suited him, because he never chose to come back to Western civilization.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.