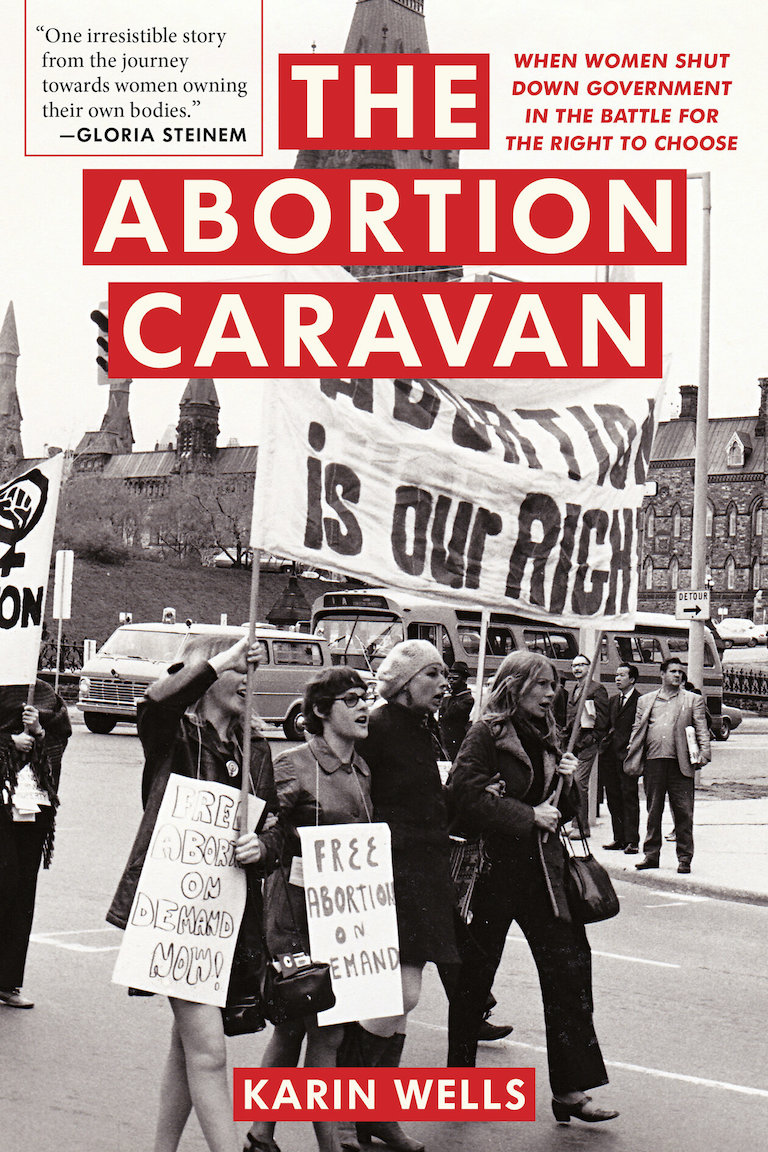

The Abortion Caravan

The Abortion Caravan: When Women Shut Down Government in the Battle for the Right to Choose

by Karin Wells

Second Story Press,

392 pages, $24.95

In 1970, seventeen women from Vancouver drove 4,500 kilometres across Canada to Ottawa, gathering supporters as they went. They invaded Parliament Hill and shut down the House of Commons.

The activists covered the spectrum of feminist demands, from daycare to the end of capitalism. But for this trek they had come together on a single issue — the need to decriminalize abortion and to gain recognition of women’s right to control their own bodies.

The figures were shocking. Nineteen out of twenty women who at that time asked their doctors for access to legal abortions were refused. As a result, the number of backstreet abortions per year in Canada between 1955 and 1969 was estimated to be as high as 120,000. Every day, women were dying or facing infertility because of botched interventions. The baby boom generation of progressive women had had enough.

Yet this cross-Canada grassroots movement — which challenged the status quo years before the #MeToo movement and managed to do so without social media or adequate funds for long-distance phone calls — has been largely forgotten.

Karin Wells, an award-winning CBC radio documentarian, made a successful half-hour documentary about the Abortion Caravan in 2010. She interviewed half of the caravan’s original members and traced their journey through newspaper stories and scrapbooks. “The joke,” she writes in her new book The Abortion Caravan, “is that the most complete record of the women’s protest journey can be found in the RCMP files in Ottawa.” Much of that record was gleaned from informants.

Although the women were well-organized and angry, they were routinely stigmatized as scruffy troublemakers and had to compete with anti-Vietnam demonstrations for headlines. They nonetheless put on a good show, including by having a huge black coffin on one of their vehicles and with various pieces of street theatre.

In the first few days, they were largely preaching to the converted, and there were no hecklers until they reached Thunder Bay, Ontario. That’s when the pushback began, including from a phalanx of hostile Catholic women, one of whom called an organizer a “slut.” From that point on, the caravan was trailed by the Ontario Provincial Police. It was also under RCMP surveillance. But the women continued to forge their way east during gruelling drives of up to 650 kilometres a day.

Using sticky Carnation milk as glue, Ottawa sympathizers had already plastered the city with posters proclaiming “The Women are Coming.” By that point the Vancouver organizers had to share ownership of the project with Toronto activists, who were themselves divided on whether men should be allowed to join the march. Despite personal and ideological conflicts, they managed to mobilize between four and five hundred women to march on Parliament Hill and to demand a meeting with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Neither the prime minister nor any cabinet member turned up to listen to their demands. “We were furious,” one of the organizers told author Karin Wells fifty years later. “We felt we needed to do something quickly. So, the coffin was outside, and we marched to 24 Sussex Drive.” Soon, hundreds of women were camped on the prime minister’s lawn, and the massive black coffin was deposited on his veranda. Two days later, forty women sneaked into the House of Commons galleries, chained themselves to their seats, and began shouting out their demands. “Strident abortion advocates force House to adjourn,” read an Ottawa Citizen headline the following day.

It would be another eighteen years before the abortion laws were finally changed, after the legal battles of Dr. Henry Morgentaler.

The Abortion Caravan is an excellent account that is a gripping read and a fascinating analysis of women’s politicization. There is a lot of detail in Wells’ book, all of it told in her chatty radio voice. Perhaps the most poignant details are ones that didn’t show up in the radio documentary — the stories the women shared on the road about their own abortion experiences, which up to then had left them feeling isolated and ashamed. Abortion was not only illegal back then; it was taboo.

Canada in 1970 was a stuffy, patriarchal country in which birth control was not easily available and unwanted pregnancies were considered immoral. The Abortion Caravan educated its participants and supporters in both the sexism of such views and the inequity of a society that showed so little concern.

Nevertheless, fifty years later, there are still regions in Canada where women struggle for access to abortions. And in the United States access to safe pregnancy terminations is being reduced.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement