Funny Bones

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the Spring 2026 issue. We went to press in December, prior to Catherine O’Hara’s passing.

Culture vultures looking for amusement in Toronto in the spring of 1972 could take in a recital by the razzle-dazzle show pianist Liberace at the O’Keefe Centre, accompanied by the husband-and-wife comedy duo Will and Fe Halliwell, billed as “The Jolly Jovers.” More sophisticated upmarket audiences might catch a film about Stravinsky at the St. Lawrence Centre or a performance of Samuel Beckett’s minimalist one-man show, Krapp’s Last Tape, at the Colonnade. But the groovier set knew of a more exciting event, one that turned out to be a major moment for Canadian comedy: a local version of Stephen Schwartz and John-Michael Tebelak’s biblical musical, Godspell. Pull-quote endorsements of its earlier Broadway production pumped up the show as “exhilarating,” “exultant” and “full of ozone and lightheartedness.” The Toronto Star’s theatre critic Urjo Kareda deployed a raft of considerably less-impressed descriptors: “irksome,” “insipid,” “clumsily over-busy” and so on.

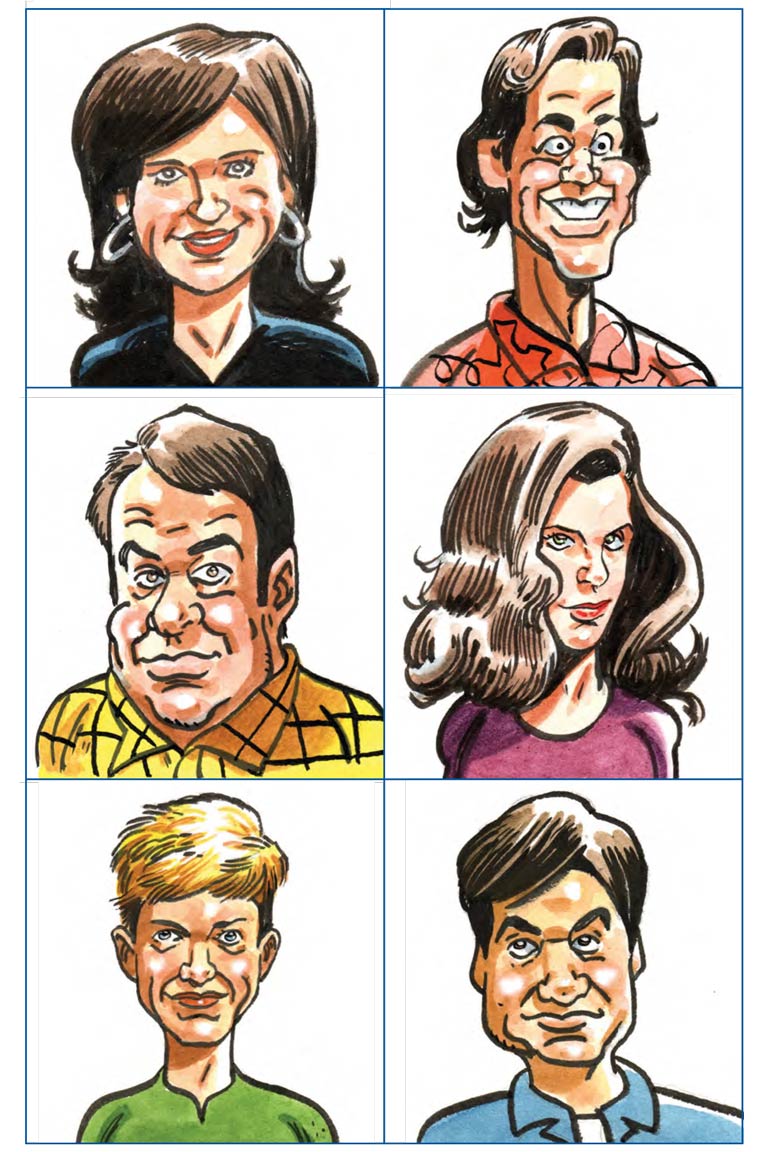

Whatever the reviews, the 1972 Toronto production of Godspell was notable for its use of local actors and performers, a great many of whom would go on to become household names, including future The Second City and SCTV stars Eugene Levy, Andrea Martin, Dave Thomas and Martin Short. Paul Shaffer — perhaps best known for his extended stint as late-night host David Letterman’s long-time bandleader and sidekick — served as the production’s musical director.

Godspell was, in many important ways, a coming-of-age point in the history of Canadian comedy. The show’s slant — a cheeky take on biblical scripture — offered a gentle rebuke against the country’s staid, solemn and overly conservative sensibilities. The playbill was dense with would-be celebrities who’d go on to light up the firmament of Canadian comedy. It was so influential that the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival showcased a documentary about the production: Nick Davis’s Judd Apatow produced — and cumbersomely titled — You Had to Be There: How the Toronto Godspell Ignited the Comedy Revolution, Spread Love & Overalls, and Created a Community That Changed the World (in a Canadian Kind of Way). The musical was, in the reckoning of B.C.-born comedy historian Kliph Nesteroff, “a paradigm shift.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The setup

Locating the genesis — or, at least, the modern origin — of Canadian comedy in 1972 may seem a bit jarring. After all, we’ve practically been conditioned from the cradle to believe Canucks possess something like a genetic predisposition toward funniness. History — that meddler — tells us otherwise.

Canada did dabble in the comic and the humorous before then. Historians often point to the pre-Confederation Letters of Mephibosheth Stepsure, by Scottish-born Nova Scotian Thomas McCulloch, as an important part of the country’s early humour. Originally published in Halifax’s Acadian Recorder between 1821 and 1823, these satirical essays offered wry social commentary on the lives of social-climbing Nova Scotians, written under McCulloch’s nom de plume, Mephibosheth Stepsure. Literary critic Northrop Frye described McCulloch’s sensibility as defining “the prevailing tone of Canadian humour ever since.” That is, “quiet, observant, deeply conservative in a human sense.” The writing is dry, and quite racist, including reflections on the “natural inferiority” of enslaved Black people trafficked in the Maritimes. Cheryl Thompson, an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Performance and author of Canada and the Blackface Atlantic, notes that racial prejudice — and its associated comic forms — flowed freely between the United States and Canada. “The border is very porous,” says Thompson. “There are a lot of Canadian performers who joined the American vaudeville circuit and then came home.”

Thompson also points out that these comic performances — based around vulgar impressions of Black Americans — were perhaps even more popular in Canada, where they had an extra “anthropological” dimension. “They’re getting entertainment and also getting a real glimpse of the Southern plantation,” she explains. “Audiences found them funny. But even the critics thought they offered a really authentic view of, like, a sunset on the Mississippi. Audiences in the north, in the U.S. and Canada, have always been enthralled with the mythology of the American South.”

The next stage of Canadian humour was marked by hokey, homespun and mostly good-natured attempts. This tack was best embodied by Stephen Leacock, which earned him naming rights for the nation’s highest award for literary humour. The small-town setting and distinctly parochial ribbing of Leacock’s 1912 short-story suite, Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town, is reflected in everything from American radio comic Jack Benny to such homegrown shows as Letterkenny and Corner Gas. Leacock prodded at small-town archetypes (modelled after his summer home in Orillia, Ont.) with a mix of critique and sympathy, though he leaned more toward the latter. His collection was a success, but Leacock’s few critics tended to put the author through the wringer for not being cynical and caustic enough. The venerable Canadian novelist and critic Robertson Davies lambasted Leacock’s perspective as little more than “intellectual fancy dress,” full of too much “pathos and melancholy.”

But humour isn’t comedy. With comedy, the laugh is the point. McCulloch, Leacock and their gently ribbing progeny fall into the category of occasionally humorous art and literature. So how did Canadian comedy take shape?

“C’mooooon in!”

Beginning its run in 1937 and wrapping in 1959, CBC Radio’s The Happy Gang marked an early attempt to set up Canadian comedy as pure entertainment. Each episode followed a familiar formula. There’d be a knock at a door, a call of “Who’s there?” and then, the reliable response: “It’s the Happy Gang!” At which point, the program’s master of ceremonies (and the gang’s de facto leader), Bert Pearl, would belt out a cheerful “Well, c’mooooon in!”

Recorded before live studio audiences and airing across the country’s radio waves daily, The Happy Gang was an especially comic twist on the variety-show format. There were songs and skits; during the Second World War, The Happy Gang even buoyed the spirits of wartime Canadians, beginning every show with a rousing rendition of the patriotic British anthem “There’ll Always Be an England.”

Though its routines may seem corny to modern ears, The Happy Gang was popular and set out to make the nation laugh in daily harmony. Marking what would be a common trope in Canadian comedy, the gang was undone not by a lack of popularity but when Pearl went stateside for a gig writing music for comedian Jimmy Durante’s NBC comedy show.

Advertisement

A new act

Canadian radio also gave rise to two performers who would help define Canada’s proud sketch comedy tradition: Wayne and Shuster. Neighbourhood friends and long-time school chums, Toronto’s Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster got their professional start on CFRB radio in 1941, co-hosting Javex Wife Preservers, which saw them humorously doling out helpful around-the-house advice. During the Second World War, they worked on the Canadian Army Radio Show and served up what Time magazine called “some perky tunes and lyrics” to soldiers across Canada and in Europe.

They offered Canadians a version of a classical comic-duo dynamic: Wayne was high-strung and wacky, while Shuster was the so-called “straight man,” offering a sturdy presence for his partner to bounce off. By 1958, the pair regularly appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show (where they’d be featured more than any other comedy duo). Many of their sketches mixed high and low forms of comedy. The classic “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga,” for instance, reimagined Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar as a hard-boiled detective yarn. In 1964, CBC presented six televised specials, Wayne and Shuster Take an Affectionate Look At…, where they highlighted the careers of such classic comedians as W.C. Fields, Abbott and Costello and the Marx Brothers. They were literate and amusing, but not necessarily gut-bustingly funny.

For all their celebrity, Wayne and Shuster’s comedy style didn’t seem equipped to deal with the cultural convulsions of the 1960s. This work would arguably fall to a younger generation, including Frank Shuster’s mentee (and son-in-law) Lorne Michaels. Before going on to create Saturday Night Live (SNL) for NBC in the mid-’70s, the Toronto-born Michaels (who was then married to Shuster’s daughter, Rosie, one of the first writers on that show) produced and co-starred in several comedy specials for CBC with his comedy partner, Hart Pomerantz. The short-lived Hart & Lorne Terrific Hour! mixed musical performances and comedy sketches dipped in a paisley palette that ostensibly pitched it to a younger and more with-it generation. The cast included future stars of Canadian stage and screen, such as Victor Garber (who would go on to play Jesus in the Toronto Godspell), Andrea Martin, Dan Aykroyd, Jackie Burroughs and Jayne Eastwood.

Canadian comedy was about to be transformed by many of those young performers. After that famous Toronto production of Godspell, Eugene Levy, Dave Thomas, Gilda Radner, Martin Short and others moved onto the main stage of Toronto’s The Second City theatre. The northern branch of the Chicago improvisational-comedy enterprise landed in Toronto in 1973 like an alien mothership luring young comics whose antennae were attuned to its strange frequency. The new operation’s American producer, Bernie Sahlins, and its director, Joe Flaherty (also from the U.S.), scouted talent from that Godspell production for their initial cast. “We were just blown away,” Flaherty, who died in April 2024, told me in 2022. “We were shocked at how good these people were.”

Part comedy, part cabaret, part experimental theatre, The Second City brought a countercultural flair to Canadian comedy, which even in the ’70s was still beholden to a certain stuffiness. As recently as 1965, the nation’s viewers were up in arms when Stan Daniels, known for his comic monologues on CBC’s newsmagazine program, This Hour Has Seven Days, gently ribbed Pope Paul VI, who was touring North America at the time. “If you watch the monologue, it’s so gentle,” says historian Nesteroff. “But it was this huge controversy. It was such a taboo. Canada was really uptight for a long, long, long time.”

Funny business

The post-Godspell comedic sea change swept across other kinds of stages, too. In 1976, stand-up comic Mark Breslin and his friend Joel Axler founded Yuk Yuk’s, a Toronto club that would nurture generations of Canadian comedians who weren’t afraid of offending the pieties of Toronto the Good. “We were trying to draw a line in the sand between people who were considered unhip and people we considered hip,” says Breslin. “The whole point of Yuk Yuk’s was to have comedy that wasn’t of your parents’ generation. It was very personal. It was completely uncensored. And that was the thing that really got us noticed.”

Like The Second City, Breslin says the comedy at Yuk Yuk’s followed American trends. By the mid-’70s, standup comedy stateside had evolved, as comedians like George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Robert Klein and Andy Kaufman were making their acts more confrontational, personal and surreal. Breslin wanted to cultivate a similar vibe. “So much of Canadian comedy had no interest to me or my company,” he says. “The paradox was that, at Yuk Yuk’s, we wanted to hire as close to 100 per cent Canadian talent as possible, but we wanted the sensibility to be very American, which we saw as sophisticated.”

In addition to fostering this more “sophisticated” sensibility, Yuk Yuk’s also tried to make stand-up viable for young comics. Breslin and Axler opened clubs across the country, curated touring festivals and, later, hosted the Great Canadian Laugh Off — a stand-up competition carrying a $25,000 prize. Such Canadian comedians as Howie Mandel, Norm Macdonald, Jim Carrey, Tom Green and Sean Cullen all cut their teeth at Yuk Yuk’s.

Canada’s standup scene would also expand to include more diverse voices. Starting in the late ’80s, Brampton, Ont.’s Russell Peters gave expression to the lives of the nation’s immigrant diaspora. Meanwhile, the 2005 filmed standup special Welcome to Turtle Island showcased the experiences of Indigenous comics. “Indigenous people in Canada love to laugh,” says Cree comedian Howie Miller, one of the featured performers on the TV special. “When we’re at our powwows, when we’re at our meetings or family functions, there’s constant laughter. Our sense of humour comes from a lot of self-deprecation. Because we’re healing.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Screen time

The cliche that comedy emerges from oppression takes different shapes in Canada. Of course, there are comics like Miller, whose comedy is partly a response to the country’s treatment of Indigenous Peoples. But more broadly, the national comic sensibility can seem like a response to our second-banana status, living in the shadow of the United States and its globally expansive entertainment industry.

That feeling of inferiority was a big part of one of the country’s greatest comedy exports. By 1976, Toronto’s The Second City grew into Second City Television, more popularly known as SCTV. The cult sketch series launched the careers of household names like Levy, Short, Martin, Thomas, Catherine O’Hara, Rick Moranis and John Candy. A parody of both the variety-show format and small-town broadcasters, SCTV tweaked the provincial sensibilities of so much Canadian comedy. Ironically, its most successful characters were arguably Bob and Doug McKenzie, two self-styled “hosers” who talked hockey and told each other to “Take off!” while draining stubbies of beer.

In the 1980s, several SCTV cast members (Robin Duke, Tony Rosato and Martin Short) would make the move to SNL, which also featured Hart & Lorne Terrific Hour! alum Dan Aykroyd in its inaugural cast. A great many other Canadian comics found viable careers in the SNL pipeline, including Phil Hartman, Mike Myers, Norm Macdonald and Mark McKinney. In 1986, CBC-TV produced The Canadian Conspiracy, a mockumentary that outlined the undue Canuck influence in American entertainment; Howie Mandel, John Candy, Eugene Levy, Martin Short, Dave Thomas, Leslie Nielsen and a number of other funny folks played spoofed-up versions of themselves.

Lorne Michaels himself would return home to help launch another cult-comedy phenomenon. Veterans of the improv and live-sketch circuit, The Kids in the Hall were a five-man absurdist troupe whose weird outsider humour would find a place on TV both here and in the United States. Their namesake sketch show aired for five seasons between 1989 and 1995 on CBC and HBO (and, later, CBS), followed by a little-loved 1996 feature film, plus several television and streaming revivals. This not-so-happy gang was ironic, acerbic and vaguely punk, geared to the tastes of the emerging grunge/gen X culture. The Kids — Bruce McCulloch, Mark McKinney, Dave Foley, Scott Thompson and Kevin McDonald — thumbed their noses at the usual national reverences, mocking parents, police, suburban ennui and even the Canadian state-funded TV system (as in their memorable sketch “Screw You, Taxpayer”).

More so than Yuk Yuk’s or even SNL (with its Canadian DNA), it’s SCTV and The Kids in the Hall that have left the most indelible mark on the country’s comic performance. Sketch comedy has dominated our TVs. This is true in more institutional forms, such as the long-running and beloved CBC shows Royal Canadian Air Farce, This Hour Has 22 Minutes and Baroness von Sketch Show. But it’s also true of cultier concerns like The Frantics and Codco — troupes that also had shows on CBC — and productions like Picnicface, TallBoyz and Hotbox, which found audiences on cable and online.

Canadian funniness is often taken as a truism. The country’s citizens are so prominent in comedy — from Leacock to Wayne and Shuster to Mike Myers, Jim Carrey, Samantha Bee, Shaun Majumder and Nathan Fielder — that it’s easy to consider humour a national trait, like politeness, raised vowels or hardiness in the face of atrocious winters. But looking back, this is a modern way of thinking about our so-considered innate hilariousness, which seems to have come even more into its own recently.

We arguably dominate popular comedy these days. Look no further than the wild success of the sitcom Schitt’s Creek or how much the critics love Fielder’s The Rehearsal. In 2024, Canadian filmmaker Jason Reitman — son of Ghostbusters director and producer Ivan — made a movie about the opening night of SNL that brought fictionalized versions of Lorne Michaels, Dan Aykroyd and even Rosie Shuster to audiences. And Vancouver’s Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg collected statuettes at the 2025 Emmy Awards (and a 2026 Golden Globe) for their Tinseltown satire, The Studio. An 80-year-old Lorne Michaels, meanwhile, capped off the 50th season of SNL with three Emmys of his own. This made his weekly sketch show the most recognized program in the history of the awards.

That same month, SNL announced the new cast members joining for its 51st season. Among the names was 29-year-old Barrie, Ont.-born TikTok comedian and actor Veronika Slowikowska — the program’s first Canadian onscreen hire in 27 years. Looking at the future of comedy, here and otherwise, it may be more accurate to say we’re so ubiquitous as to seem almost invisible. A “Canadian conspiracy,” indeed.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement