Reel Failure

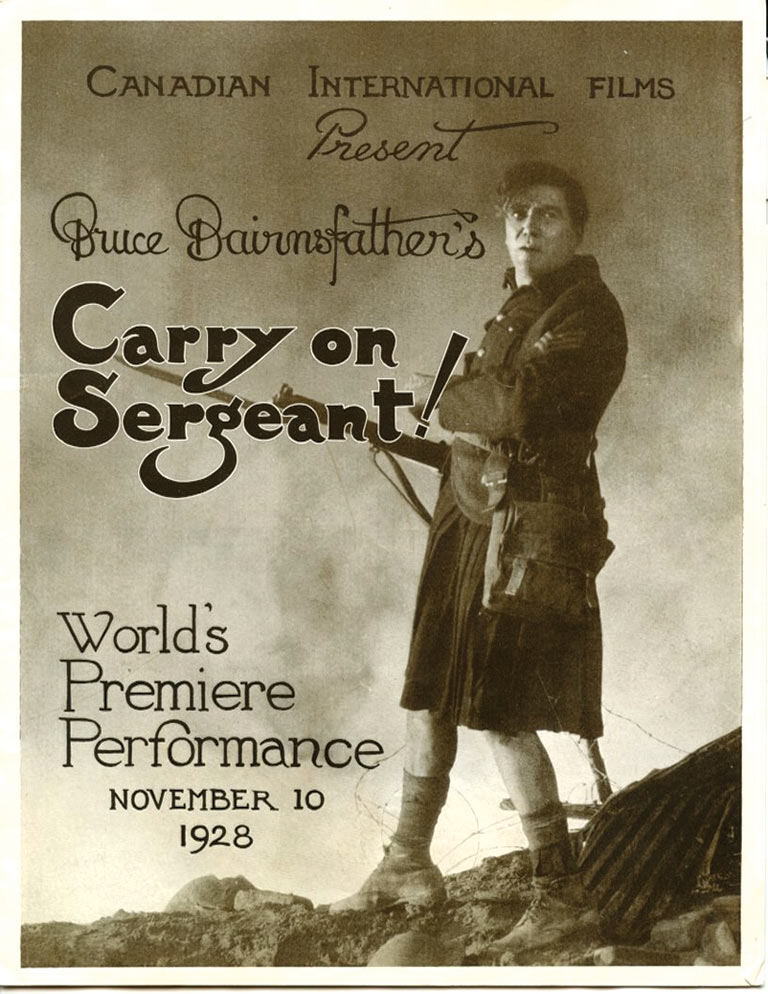

On November 10, 1928, The Marquee of the Regent Theatre on Toronto’s Adelaide Street West was brightly lit, announcing the world premiere of Carry On Sergeant! Hyped as “Canada’s first mammoth motion picture production,” the war epic had been a year in the making. Now the attention of Toronto’s elite was focused on its gala opening. Optimism ran high that Carry On Sergeant! would prove that Canada could produce big movies of “artistic merit, capable technique, and of universal appeal,” as a souvenir program declared.

In the mid-1920s, Canada’s cinemas were dominated by Hollywood movies, many of which stereotyped the country as a land of ice and snow. Numerous film companies had formed and folded in Canada in the preceding decade, but few quality features had been produced. Whatever profits were made from these films went into the pockets of unscrupulous promoters, leaving investors wary of such movie-making. Carry On Sergeant! was supposed to turn this disappointing trend around.

The elegantly dressed audience settled into the Regent’s plush seats as the lights dimmed, the live orchestra started up, and the black-and-white opening scene rolled across the silent screen. The film told a tragicomic story of four Canadian soldiers in the First World War and included some candid scenes that were shocking for their time. One hour and forty-seven minutes later, audience members applauded, and reviewers rushed to make their deadlines. The verdict? Mixed.

Fourteen days later, the film ended its Toronto run. By Christmas it was playing nowhere. The costly and much hyped film was not going to lead the Canadian film industry to glory after all. Instead, Carry On Sergeant! not only proved to be a spectacular flop, its failure also impeded a big-budget Canadian film industry from developing for many decades.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The saga began when George Patton — the ambitious head of the Ontario government’s motion picture bureau, which produced educational documentary shorts — sent a delegation to New York to secure foreign distribution for its films. This led to a deal in spring 1926 with Cranfield and Clarke, an independent British distribution firm.

W.F. Clarke, a principal of Cranfield and Clarke, opened a branch office in Toronto and soon started promoting the idea of producing feature films on “Canadian stories with Canadian background, written by Canadian authors.” Within months, he formed a production company called British Empire Films of Canada, which later evolved into Canadian International Films (CIF), and began luring investors with an avowedly nationalistic pitch.

By early April 1927, Bruce Bairnsfather was announced as the scenario writer for the company’s first movie. He was a Brit, but a major name. While fighting in Europe during the First World War, the aspiring artist had sketched cartoons depicting life on the front lines. The resulting misadventures of Old Bill, his walrus-mustachioed character, won credit for boosting morale after they appeared in magazines and bestselling books. Postwar, Bairnsfather performed on the vaudeville stage and wrote a play called The Better ’Ole, with Old Bill as its protagonist, that proved hugely popular onstage and in two film adaptations. The 1926 Hollywood version was just finishing a six-month run in cinemas when Bairnsfather was approached about joining the Canadian moviemaking scheme.

For its debut, the company wanted an epic depicting Canadian wartime heroism, a savvy response to Hollywood’s almost-exclusive focus on American soldiers. Bairnsfather created a story titled Carry On Sergeant! that centred on the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, where, during one of the earliest German uses of poison gas, Canadians held the line when other men fled. CIF felt that Bairnfather’s firsthand experience in that battle would ensure a high degree of authenticity and would therefore be more valuable than any actual experience in making films. He was eventually elevated to the position of supervising director, with a level of control over all aspects of the movie that was unprecedented, even for veteran Hollywood directors.

Bairnsfather wholeheartedly believed that a high-quality film would form “a splendid nucleus for the beginning of a great motion picture industry in Canada,” as the Toronto Star newspaper paraphrased. Radiating this enthusiasm, he joined Clarke at a series of meetings and luncheons around Ontario to drum up financial backing. The most prominent of these occurred at the National Club in Toronto on July 8, 1927. Before an audience of pre-eminent businessmen and politicians, Ontario Premier Howard Ferguson endorsed Clarke’s film company as a sound organization and strongly urged investment as a patriotic duty. Moreover, he promised his government’s full co-operation, which led to the province leasing its studios in Trenton, Ontario, to the venture for a pittance. The necessary investment funds were raised in no time.

Seemingly everyone — investors, government, and the press alike — was enthusiastic to see a distinctly Canadian war movie succeed. No voice of reason publicly urged caution.

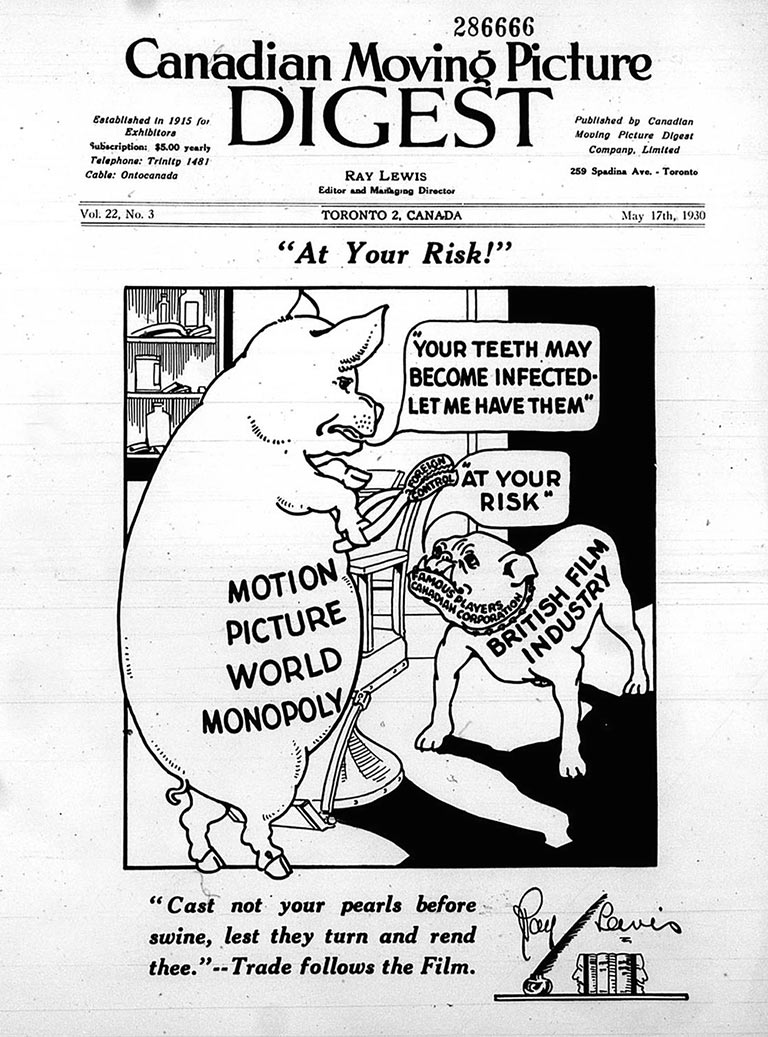

An amicable local press reprinted anything leaked by publicity-seeking company officials, including dubious reports of a five-million-dollar government investment and a rumour that former Prime Minister Arthur Meighen had been named company president. “It was good newspaper copy,” the company claimed in its defense. But Ray Lewis, editor of the Canadian Moving Picture Digest, argued that this “cheap publicity” risked discrediting the venture as just another easy-money scheme.

Recognizing that his epic’s budget was quite modest by Hollywood standards, Bairnsfather prioritized finding “undiscovered ability at a small salary,” instead of big-name actors, when he arrived in Trenton in mid-September. English stage actor Hugh Buckler was cast in the lead role of Bob MacKay, a locomotive-works employee who fights overseas and quickly earns promotion to sergeant for his battlefield heroics. Comedian Jimmy Savo, cast as MacKay’s ne’er-do-well friend Syd Small, was a vaudeville star who had never acted in a feature film. Niles Welch, who played their commanding officer in the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, was the only actor with substantial motion picture experience.

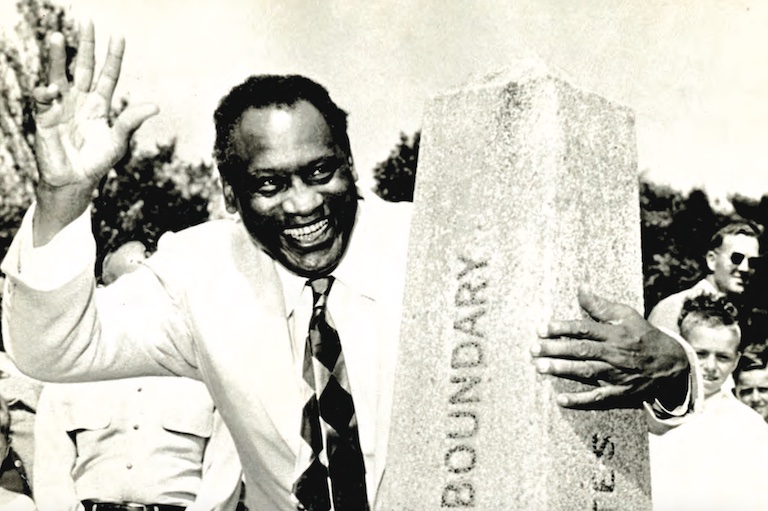

Hundreds of people from the Trenton area were cast as extras. Many were simply spotted in their front yards, or seen standing among the crowds gathered to watch the filming, and were found to fit the necessary characteristics of particular roles. Other extras came from farther afield, like the Montrealers recruited to play French village girls or the Black Pullman porters hired to portray French colonial soldiers. The movie production was a boon for Trenton, a railroad town suffering economically. Extras made a dollar a day; labourers earned a bit more to dig trenches or to build sets. Locals found it a lark to charge through parks in full military attire, brandishing rifles affixed with bayonets.

In Trenton, Bairnsfather discovered that the antiquated film studios needed extensive renovation and improvement. He found a vacant cold-storage plant with a hole in its roof to house larger sets — including an entire Paris street, complete with cafés, shops, and window boxes. A locomotive works and a hotel in Kingston, one hundred kilometres away, were used for location shooting. The company also rented space in downtown Trenton for the wardrobe department and stocked it with uniforms and equipment borrowed from the Black Watch regiment as well as military kit for Germans and colonial French characters rented from New York.

Filming got underway in late November 1927. With the interior sets experiencing construction delays, Bairnsfather put his faith in an almanac that predicted snow would hold off, and started shooting the exterior scenes. Almost immediately the Trenton fire department was called in to clear a sudden snowfall out of the muddy trenches with its hoses.

Bairnsfather’s cinematic ambitions are illustrated by the account he later wrote in his autobiography, Wide Canvas, of filming refugees fleeing Ypres under bombardment — one of the film’s most impressive, though brief, sequences. As a setting, Bairnsfather located a patch of poplar trees near St. George’s Cemetery, which resembled the Ypres area. The crew added some splintered trees, dug shell holes, and scattered debris. Several houses were built just to be torched. Dynamite was buried all around, each stick with the power to send mounds of dirt cascading fifteen metres into the air. The explosives, wired to a central control manned by Bairnsfather, were carefully sequenced to appear as “shells bursting indiscriminately” while refugees rushed through a harsh November rain.

Advertisement

In Bairnsfather’s telling, such scenes were a delicate ballet, as hundreds of extras manoeuvred through sets lined with explosives in carefully rehearsed patterns, risking that any “mistake in timing might easily have been fatal.” A Toronto Star reporter who visited the set described Bairnsfather as a “tactful, intense, and absolutely unswaggering artist-director.” But many observers later complained that Bairnsfather’s set was disorganized and chaotic. Though well-intentioned, Bairnsfather was in over his head, wasting money and blundering his way through the five months of filming.

Acrimony between Bairnsfather and Clarke, the general manager of CIF, was frequent and open. The director resented Clarke’s presence on-set as infringing on his control over the movie. While some disputes could be chalked up to the usual producer-director issues, their personal feud ran deeper. Paranoid that his ideas would be stolen, Bairnsfather refused to show anyone — management, crew, and actors alike — his shooting script. This was the version of the script that included detailed cinematography instructions such as camera shots, props, and locations. “The result was that neither actors, art directors, or other technicians knew what to prepare for,” recalled Gordon Sparling, who worked as an assistant director on the movie early in his long filmmaking career. “It is no wonder, then, sets were built and never used, that the whole sequences covering many days’ work were later discarded, that actors were retained in idleness sometimes for weeks at a time.”

Refusing to accept any advice, the director resented an experienced associate director the company had hired to help him and ignored the man until he finally left. Production managers came and went without enjoying the confidence of the director. Bairnsfather argued with, and finally fired, a continuity writer who had been brought over from England, all expenses paid. (The job of a continuity writer, particularly important in silent films, was to visualize the movie’s story in a series of scenes, from beginning to end.) If Clarke hired someone, Bairnsfather would fire the person, and vice versa. Bairnsfather spied on cast and crew constantly for signs of disloyalty. The director even had a private phone line installed because he thought the company telephones were being monitored.

Bairnsfather assumed all unstaffed duties, eventually acting as title writer, art director, costume supervisor, and military consultant. “Not because I wanted to be,” he later insisted in his autobiography, “but because I … was fighting for the life of the picture.” Clarke, whom Bairnsfather eventually barred from the set entirely, was no angel either. Business partners later decried his impatience, lack of business sense, and refusal to heed advice. According to Peggy Dymond Leavey’s book The Movie Years, one colleague called him “a crook.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

After filming ended in mid-May 1928, their conflict culminated with CIF seeking a court order to have the county sheriff seize the shooting script and still-photo negatives, which the company claimed Bairnsfather and Bert Cann, his trusty head cameraman, had “wrongfully detained.” The bizarre situation was reported widely in the American trade papers, though no Canadian newspapers picked up the story.

The final straw was Clarke’s plan to produce a series of comedy shorts, which Bairnsfather considered a misuse of funds earmarked for Carry On Sergeant!. Bairnsfather lodged complaints with some of the most heavily involved shareholders. In the resulting boardroom shakeup, Clarke was ousted as general manager.

Bairnsfather and Cann got to work on editing the picture, though neither had experience. Weeks stretched to months as they struggled to shape an incredible 160,000 feet (48,768 metres) of film footage — more than double that usually shot in Hollywood — to a feature length of 9,700 feet (2,956 metres).

A surprise preview screening at the Runnymede Theatre in Toronto in late August 1928 was encouraging. The film ended with “a prolonged storm of applause that almost broke into cheers,” Toronto Star art critic Augustus Bridle reported. Though Bridle had some positive things to say about the film, he suspected the audience cheered because, out of patriotism, they wanted to like the movie they’d heard so much about. But, he wrote, there was nothing distinctly Canadian about Carry On Sergeant!

When Carry On Sergeant! opened to the general public on November 12, after its gala premiere, critics were mostly positive about its realism and camera work. But even the most enthusiastic had to admit weaknesses in the meandering storyline. The Toronto Evening Telegram called the plot “vague and rambling.” Most damning, an unsigned review in the Toronto Star not only dubbed it “amateurish in construction” and “uninteresting and tiresome to watch” but also made a harsh prediction: “The hard road for Canadian films will be made much more difficult owing to the puerilities of this picture,” the anonymous reviewer asserted. “American film competition is overwhelming enough without making a Canadian film that is a positive handicap because [it is] discreditable alike on patriotic, moral and artistic grounds.”

Protesters soon gathered outside the Regent, angry that the married protagonist Sergeant MacKay succumbs to the temptations of a bar girl in a climactic scene, only to seek his end on the battlefield out of remorse. Many viewed the scene as an insult to Canadian soldiers. Some shareholders, embarrassed and worried about protecting their investments, called for the film to be re-edited to remove the offending scene. Others defended the film and its director. Reporters sought comment from every politician, businessman, or military officer they could assemble, with their endorsements or criticisms splashed across the front pages. Looking on the bright side, some observers were convinced that the scandal helped at the box office.

It’s unclear how much money Carry On Sergeant! actually made, after the costs of publicity, full orchestra accompaniment, and live sound effects created by stagehands were deducted. The weekly show business newspaper Variety reported revenues of $9,000 in the film’s first week, well below the $15,000 earned in the same week by the Hollywood gangster flick Underworld. (Canadian and U.S. dollars were trading at par in 1928, making it easy to compare revenues.) The box office improved to $10,000 in its second week, but the film was still out-earned by competition. Despite these somewhat encouraging figures, Carry On Sergeant! closed its Toronto run on November 24, a move so sudden that the Regent had nothing booked in its place. In its announcement, CIF offered no specifics: “The directors have decided to spend no more money or take no more interest in the picture.”

Advertisement

All fall there had been reports that American or international distribution deals were imminent, though nothing was ever signed. The British company that was originally supposed to distribute the film, Cranfield and Clarke, had gone bankrupt earlier in 1928. CIF continued to seek a distribution deal, an all-but impossible task for an independent producer in a new era of vertical integration where conglomerates controlled the production, distribution, and exhibition of films in North America. CIF’s publicity man invoked nationalism and promises of personal appearances by Bairnsfather to secure bookings in the Ontario cities of London, Brantford, St. Catharines, Kingston, Barrie, and Trenton.

But these one-offs were no substitute for a distribution deal with Famous Players Canadian Corporation, the only company that could offer nationwide bookings. Early in the enterprise, investors and the trade press alike had taken for granted that a deal with Famous Players would be secured. The cinema chain’s managing director, Nathan Louis Nathanson, had nationalistic leanings. He was likely sympathetic to CIF efforts and had booked the film’s opening run in the Regent, the 1,500-seat movie palace that was the nucleus of the Famous Players Canadian chain, as well as at a handful of affiliated cinemas. But Nathanson had to contend with Adolph Zukor, the powerful head of Famous Players’ parent company, Paramount Pictures, who disapproved of encouraging the competition.

Aspersions were cast that Famous Players was intentionally freezing out Carry On Sergeant! at the behest of American interests. Ontario’s Attorney General William Herbert Price, deflecting allegations that the government had ordered the film withdrawn, speculated as much. Famous Players responded that it had given Carry On Sergeant! a fair chance but had lost money when audiences ignored it.

By Christmastime, Carry On Sergeant! was shelved. CIF put all plans for further features on hold until the distribution rights to the first film could be sold. Clarke had faded from public attention. A disheartened Bairnsfather returned to New York.

Carry On Sergeant! returned to the headlines when the Canadian Moving Picture Digest, a florist, and a printing company initiated bankruptcy proceedings against CIF. By this time, the once enthusiastic Ontario government had distanced itself. “I am not interested in the matter at all,” Attorney General Price asserted. “The only people who can say anything about this picture are those who put their money into it.” CIF’s counsel secured a three-month stay to attempt to right its finances, still confident that distribution deals in Britain and the United States were imminent. Similarly, there were persistent rumours that, given how much footage had been shot, Carry On Sergeant! could be completely re-edited and re-released.

The company’s efforts were stymied, however, when numerous insiders laid bare all of the production’s follies in the press. Now, a local media that had treated the enterprise with kid gloves since the beginning proved all too willing to savage Carry On Sergeant! Adding insult to injury, in early February the Gaumont-British Picture Corporation issued a press release clarifying that its film Carry On was specifically not connected with the CIF picture bearing a similar name.

Lewis, editor of the Canadian Moving Picture Digest, now insisted that she had predicted a disaster all along but had kept silent out of nationalist sentiment. Because she felt the finished film looked cheap — like “it could have been made for seventy-five thousand [dollars]” rather than the reported three hundred and fifty thousand (plus one hundred and fifty thousand for promotion) actually spent — Lewis intimated that Clarke had been just another schemer lining his own pockets.

Shortly afterward, in a behind-the-scenes exposé published in the Canadian Moving Picture Digest, Sparling, the assistant director, bemoaned Carry On Sergeant! as a “tragedy” that had dashed “the hopes of a Canadian motion picture industry.” Sparling, who had moved on to a job in the federal government’s movie bureau, laid the blame on Bairnsfather’s “inexperience, bull-headedness, and extravagance.” The article was a litany of chaos on-set, infighting with management, bad decisions, and wasted money — all publicly exposed for the first time.

A few weeks later, again in the Canadian Moving Picture Digest, an anonymous CIF insider piled on, citing examples of budget extravagances and disputes between director and producer. He leaked salary details for not only the entire cast and crew but also the company officers, revealing that Clarke and others had drawn salaries of $1,000 per month for doing little production-related work — which many interpreted as “graft.”

Calling Sparling’s exposé a “slanderous, libelous and untruthful attack” intended to make him the “scapegoat,” Bairnsfather angrily replied from New York. Emphasizing the personal and financial sacrifices he had made to complete Carry On Sergeant!, Bairnsfather declared that he’d endured intolerable and “monstrous conditions” working under Clarke. He came off as defensive and paranoid. The gruelling production and the film’s failure left Bairnsfather “disillusioned and deeply upset,” Sparling conceded years later, admitting that he “might have been too hard on old Bairnsfather and not hard enough on the distributors.” Never a wealthy man, Bairnsfather left Trenton in financial hardship.

Back in bankruptcy court in late May 1929, the proceedings were halted when, as the Toronto Star put it, “the film company had made satisfactory financial arrangements to pay the proper claims.” Behind the scenes, the Ontario government had quietly settled CIF’s accounts to quell criticisms of wealthy and influential investors who blamed Premier Howard Ferguson personally for having persuaded them to invest.

The film’s failure has often been attributed, even by Bairnsfather himself, to its being released as a silent movie just as talkies hit the scene. Indeed, when Carry On Sergeant! opened, Mother Knows Best — the first talking picture to play in Toronto — was drawing crowds uptown. But industry observers remained unconvinced that sound was a requirement — or even a benefit — for film. And, as it took several years for all Canadian cinemas to undertake the costly conversion to sound, audiences still accepted silent films.

In the 1930s, Sparling saved a negative of Carry On Sergeant! that had been slated for destruction. It was eventually deposited with the Canadian Film Archive in 1951, where it sat forgotten for decades. More than fifty years after its initial release, a new print of Carry On Sergeant!, restored with Sparling’s assistance, was aired on CBC Television to finally earn a national audience. Today, film buffs can view the movie on Library and Archives Canada’s YouTube channel.

Watch the movie

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement