Around the World in a Canoe

In a dusty glass cabinet sharing the front room of a turn-of-the-century house at 206 Beaver Street in Banff sits a model of a curious looking three-masted sailboat. Its figurehead is a ferocious eagle, something more natural to a West Coast native war canoe.

The house was owned by Norman Kenny Luxton, and the model is indeed that of a Nootka canoe —a canoe that 100 years ago this spring took him from Victoria to Fiji and went on to become the only canoe ever to have sailed sixty-four thousand kilometres around the world.

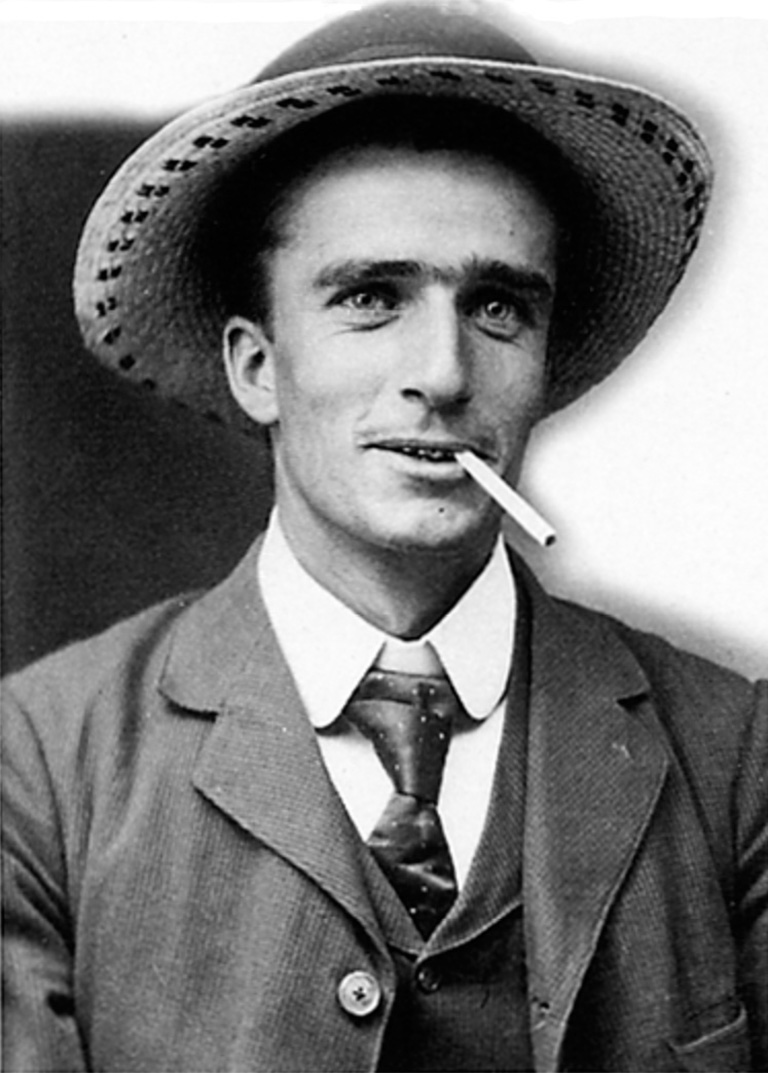

Luxton was a prairie lad born November 2, 1876, in Upper Fort Garry to the founder of the Winnipeg Free Press. After apprenticing with the Indian Agency where he claimed he once met Louis Riel, and an eight-year stint with the Calgary Herald, he grew restless, and at the age of twenty-five found himself on the West Coast working for the Vancouver Sun. At a waterfront bar one night in 1901, he met a swashbuckling fortyish sea captain named John Claus Voss. Luxton had never sailed in his life, but he was ripe for romance, adventure, the meaning of life, and lots of money. And he had the newspaperman’s eye for a story.

Over a beer Luxton hatched a plan to the barrel-chested Jack far with the handlebar mustache. Voss later described it: “Mr. Luxton ... asked me if I thought I could accomplish a voyage round the world in a smaller vessel than the American yawl Spray, in which Captain Slocum, an American citizen, had successfully circumnavigated the globe.”

Of course, Voss thought, and immediately proposed that they make it a real challenge by doing it in a canoe. Luxton sweetened the deal with five thousand U.S. dollars, the result of a bet with some Americans. The venture was a publicity stunt from the start, hut the two’s motives were different. Voss smelled high-seas adventure.

Luxton smelled money. Luxton was a visionary, a promoter, always looking to new ideas and the future. “When I get to Australia I am going to try and do business in timber,” he wrote his mother before their departure. Voss and Luxton signed an agreement, and weeks later purchased a used twelve-metre, red-cedar dugout canoe built in Clayoquot, B.C.

They took her to Spotlight Cove on Galiano Island, and with the assistance of a shipwright named Harry Vollmers got her ready to meet the rigours of blue-water sailing. Oak frames reinforced the hull and eighteen centimetres were added to her gunwales.

They ballasted her inside and added a keel with 170 kilograms of lead on the bottom. Rigging her with three masts and four sails adding up to twenty-one square metres, they decked her over and built a 1.5 x 2.4 metre cabin on top.

Ahead of her time, all running gear led back to the cockpit in the manner of modern racers so she could be easily sailed single-handedly. Two galvanized water tanks and storage completed the conversion.

She was christened Tilikum (Chinook for “friend ”) and taken for a shakedown in coastal waters. “She would have been a bit of a dog to steer,” says Ron Mack, master sail-maker, who last year was commissioned by the Maritime Museum of British Columbia to re-create the sails. “In a sloppy sea that rudder wouldn’t touch water.” But it seems Voss and Luxton thought otherwise. “I have seen such mountains of water as I never could dream of hut the Tilikum went over everything like a bird, and wind has no effect on her at all. I am more than ever convinced that she is safe as any boat on the sea,” Luxton wrote his mother.

Satisfied with her performance, the boys provisioned her with canned goods, sea biscuits, a medicine chest, two rifles, a shotgun, a pistol, a camera, a sextant, a compass, and a chronometer. A Victoria secondhand store yielded a Pacific Ocean directory and chart. They were ready to set sail.

At six o’clock on the morning of May 21, 1901, the intrepid pair caught the wind out of Victoria harbour. They were weatherbound at first, anchoring at Port San Juan and Dodges Cove on the west coast of Vancouver Island, where they were shot at while looting some Indian burial grounds for “curios” to sell on the trip. Finally, on July 6, they set their sails for the Marquesas Islands in the South Pacific.

One day Voss didn’t like the way Luxton was handling the boat. He grabbed him by the collar and threw him into the cabin, threatening to kill him and throw him overboard.

Just eight days into that first ocean leg, 1,170 kilometres from Vancouver, Luxton discovered that seawater had leaked into their provisions. Biscuit boxes were bursting, cans were swelling, and everything was mouldy. “It was so bad that I had to pick over our oatmeal flake by flake, all according to colour. It was the whites against the greens, the latter always winning ten to one.” But they caught a few fish and a sea turtle, and pressed on.

Making 145 to 160 kilometres a day, they encountered some vicious storms and waves, many with faces much longer than their boat. But Captain Voss was an expert in the use of a sea anchor, one that he had designed himself, and it helped him keep the small craft headed safely into the wind over the open sea.

Bypassing the Marquesas Islands due to strong winds, their first land was at Penrhyn Island, one of the Cook Islands. Here they met two British traders, Dexter and Winchester, who for three weeks treated them to the charms of the islands, from feasts to princesses. The islanders generously repainted and restocked their boat.

Satiated, they weighed anchor and set course on September 26 for the Danger Islands and Samoa. After the joys of the island stop, sharing a small cabin for days on end began to wear thin. One clay Voss didn’t like the way Luxton was handling the boat. He grabbed him by the collar and threw him into the cabin, threatening to kill him and throw him overboard. Luxton’s response was to calmly have his dinner and wash the dishes.

Then, he grabbed the .22 calibre pistol and held it to Voss’s head, ordering him into the cabin and locking him inside until they reached Apia Harbour in Samoa. Luxton was clearly getting fed up. “I have made up my mind that when I get to Sydney that will be the last time I get into that canoe to cross any open sea,” he wrote his mother when they arrived in Samoa.

Voss never mentioned the incident in his account. On approaching Suva, Fiji, Luxton was again on watch. About 2:30 in the morning he heard breakers and wakened Voss to ask his advice. “Keep her on course,” Voss sleepily replied.

At that instant they were on top of a reef and broadsided by a massive wave that rolled the canoe onto its side. Luxton was pitched overboard and lost sight of the boat. He knew he was inside a shark-infested lagoon, so he decided to try and stay on the reel, hoping Voss would find him in the morning. But the pounding made it impossible.

“Extra large waves, casting tons of water over the reel, would throw me further into the lagoon. Frantically would I put on more steam to reach the reef away from the sharks, only to get more Hell from the coral,“ he wrote. He didn’t remember how he got there, but by morning he found himself on an uninhabited beach “as raw as a butcher’s hind-leg of beef.”

Voss, who had given him up for dead, nursed him back to health while spending a couple of days repairing the canoe. On entering Suva harbour, a weakened Luxton consulted a doctor, who advised him not to continue with the voyage. He set out to find a replacement, but Voss already had a man, a Tasmanian named Louis Begent. Voss and his new crewman reprovisioned, including liquor, which to Luxton was taboo at sea. Luxton secured passage on the SS Birksgate to Sydney.

Arriving in Sydney, he waited for Voss and the Tilikum. Ten days overdue, he had given them up for lost. But early one sunny afternoon, John Voss stepped up on the veranda where Luxton was sitting and told him of storms never dreamed of. And, shockingly, the news that his mate Begent had been swept overboard and lost at sea with the ship’s only compass.

As Voss recounts the story, he had been in the cabin repairing their compass and had just passed it out to Begent when “I saw a large breaking sea coming up near the stern.“ He shouted a warning, but it was too late. The rogue wave hit them, knocking Voss back against the cabin. By the time he regained his balance, his mate was gone. Because of the strong wind and waves, he couldn’t beat back to find him. Luxton wrote afterwards he never believed Voss’s story.

He knew Voss’s dark side and was convinced he had killed Begent in a drunken fight. After the news of the death, both Luxton and the local newspapers dropped interest in the boat’s story. Luxton tried to coax Voss into abandoning the trip. But Voss’s 2,000 kilometres to Sydney “steering by the sun, moon, stars and ocean swell said a lot for his capabilities as a seaman. He was determined to continue the voyage in the Tilikum.

To raise funds for a new mate and fresh provisions, he exhibited the canoe in Sydney, then put her on the train to Newcastle a hundred kilometres north.

Just before leaving Newcastle, Voss reported seeing Luxton, who again pleaded with him to abandon the venture. That was the last they saw of each other. Voss sailed off to Melbourne with a new mate. At Melbourne, Voss had more bad luck. At another exhibition, Tilikum was sent crashing to the ground when a hauling block broke. The fall split her hull in five places.

Voss successfully sued for the £200 needed for repairs. Changing mates yet again — he hired Buckridge, who had been part of Robert Scott’s first Antarctic expedition — he set sail for Adelaide, then Hobart, Tasmania, and then to Invercargill and other spots along the coast of New Zealand, in Wellington, after a show and talk on Tilikum, a young Royal Navy lieutenant named Ernest Shackleton came up and shook his hand.

Such recognition warmed Voss and inspired others: in Auckland, Buckridge announced he was leaving the Tilikumto sail his own small boat and race him to England. Voss signed on yet another, Herbert Macmillan, a former man of the cloth, and on August 19, now nearly two years and three months since leaving Victoria, shaped a course for the New Hebrides. They lowered their Canadian Ensign to half mast as they crossed the point where Voss had lost Begent to the sea.

Thousands visited her in Johannesburg and Pretoria, including war hero General Louis Botha, “who told [Voss] that he would go through another South African war than attempt to cross the Atlantic in the Tilikum.”

After a cordial stay with some missionaries in the New Hebrides, the two aimed the canoe due west for the Torres Strait. Apart from some food poisoning on Voss’s part, the trip through the strait and across the Gulf of Carpentaria was uneventful. They made for the Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean.

The wind died clown on their approach. With the boat becalmed, Voss and Macmillan rested for the night. But morning found them drifted far away. They tried sailing back into the wind, but the drifting’ current was too strong, and they soon lost sight of the islands. Their only option now was to push on to their next destination, Rodrigues Island, more than three thousand kilometres to the west, without fresh provisions. Down to just a few pints of water, they prayed.

Five days later, luck brought them torrential rains and they filled their tanks. On November 28, 1903, they sighted Rodrigues Island. Following a short stay enjoying the hospitalities of the island folk, they hit the open ocean for Durban, South Africa. They made good time and on December 22 sighted the South African coast. Visions of Christmas dinner filled their heads. But two wicked storms tossed them about for three days. So they ate their last corned beef for Christmas dinner, then put into Durban.

It appears they neglected to tell anyone. Back in Australia, The Observer of Adelaide reported on January 30, 1904: “It is feared that the 4-ton yacht Tilikum... has been lost. Today the tiny vessel is 119 days out from Thursday Island to Cocos Island, a distance of 2,800 miles and she has been declared missing.” The newspaper continued with an obituary of the whole Tilikum odyssey since leaving Victoria harbour.

In Durban, Voss heard the news that his former mate Buckridge had perished in his attempt to beat him to England. Macmillan left him to seek a fortune in the gold and diamond mines of South Africa. But the Tilikum was again the star of travelling shows.

Thousands visited her in Johannesburg and Pretoria, including war hero General Louis Botha, “who told me that he would go through another South African war than attempt to cross the Atlantic in the Tilikum.” Following a train trip down to East London, he hired his tenth crew member and sailed around the Cape of Good Hope to Capetown. There his eleventh and last mate, Harrison, met him for the voyage across the South Atlantic to Pernambuco (Recife), Brazil.

Harrison, who suffered from consumption, spent most days hanging over the side with seasickness, so Voss altered course and landed instead at St. Helena, where Napoleon Bonaparte had been banished. Harrison recovered and continued on with Voss to Brazil. On May 20, 1904, just a few hours short of three years after his departure from Victoria, they anchored at Pernambuco. He wrote of the milestone, “Thus the Tilikum had succeeded in crossing the three oceans and the contract I had entered upon with Mr. Luxton was fulfilled.”

At Pernambuco, the British consul congratulated the two and treated them with free railway passes to see Brazil. On the afternoon of June 4, they were towed out of the harbour to set course for the final leg, to London. On the way, they pulled into the Azores for more of the royal treatment before pressing on to England.

Finally, at four o’clock in the afternoon of September 2, 1904, Tilikum sailed into Margate, England, to a cheering welcome, exactly three years, three months and twelve days after leaving Victoria.

Voss’s account of the voyage comes to a rather abrupt end at this point. With the help of Shackleton, whom he had met in New Zealand, Tilikum was exhibited at Earl’s Court for the Navy and Marine Exhibition of 1905. Voss was elected a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, where he became a popular lecturer. But after this he appears to have faded from public view. Author Francis Dickie, in an October 1959 article in Seacraft, said an unknown researcher claimed he had been lost at sea in 1913 on a venture out of Yokohama. But according to his daughter, Caroline Kuhn, he ended up driving a taxi in Tracy, California, where he died in 1922.

The Tilikum came close to suffering a similarly ignoble fate. After her Earl’s Court showing, she changed hands a few times and was abandoned on the Thames in 1929. Inquiries by an unnamed Canadian naval officer led to London’s B.C. House advertising as to her whereabouts. A response came back from a Mr. Byford, on whose property she was rotting. She was shipped back to Victoria on the Furness Line in 1930.

The Empress Hotel provided a display site next to the Crystal Gardens on Douglas Street. In 1936 the Thermopylae Club restored her, and in 1940 she was moved to Thunderbird Park. She was relocated to her present home, the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, in 1965.

Luxton worked his passage from Sydney back to Victoria as an able seaman and found his way to Banff, there marrying the daughter of David McDougall, one of the region’s most prominent citizens. He opened a tourist shop, a taxidermist shop, and started Banff’s first newspaper, the Crag and Canyon. Luxton lived at 206 Beaver Street until his death in 1962.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.