Changing Minds

On any given day, patients at Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences might make use of the Brain Stimulation Clinic, the Geriatric Inpatient Program or the outpatient clinics for mood disorders and anxiety. Whatever the program, patients at the Whitby, Ont., hospital have care plans built on science, compassion and the goal of enjoying life again.

Such facilities are a far cry from the institutions that once operated here. “Mental health services weren’t in communities in the 1700s and 1800s, and conversations about mental health weren’t being had back then,” says Marion Cooper, the president and lead executive officer at the national office of the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA). “Asylums, not hospitals, were the standard of care. People spent their lives institutionalized in deplorable conditions, and most lost contact with family. They experienced a tremendous stigma, as well as a deep sense of isolation. How we thought about psychiatric illness was so different centuries ago.”

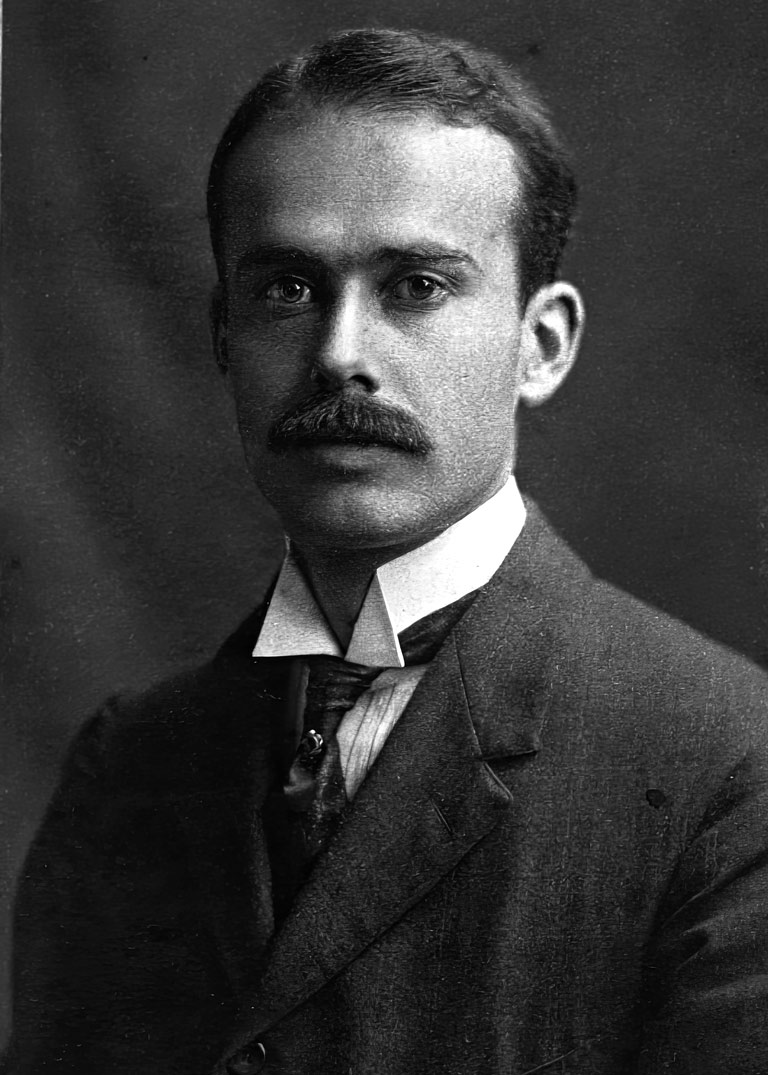

Indeed, it wasn’t until 1918 when a doctor from a small town in Ontario — who suffered from severe depression himself — put us on a path toward change. Dr. Clarence Hincks was instrumental in the creation of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene, now the CMHA. And while those who deal with mental illnesses will tell you we still have work to do when it comes to support and breaking the stigma, thanks in part to Hincks and the creation of the CMHA — which is celebrating its 100 years as a federally recognized organization this year — we’ve come a long way.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

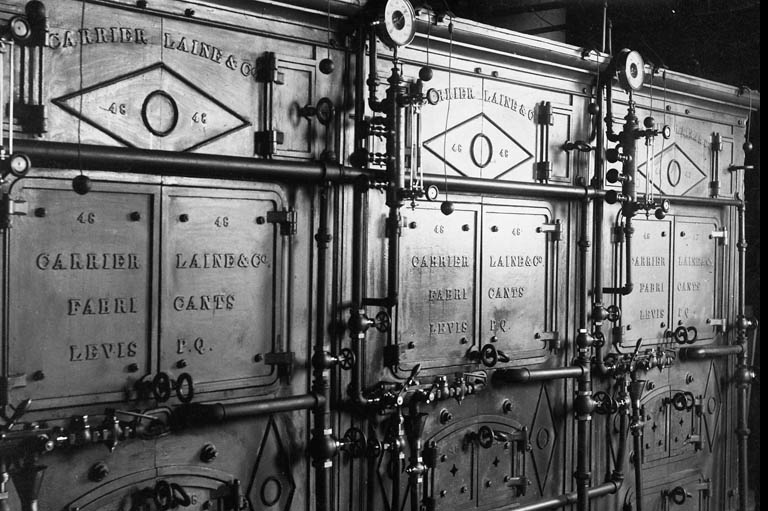

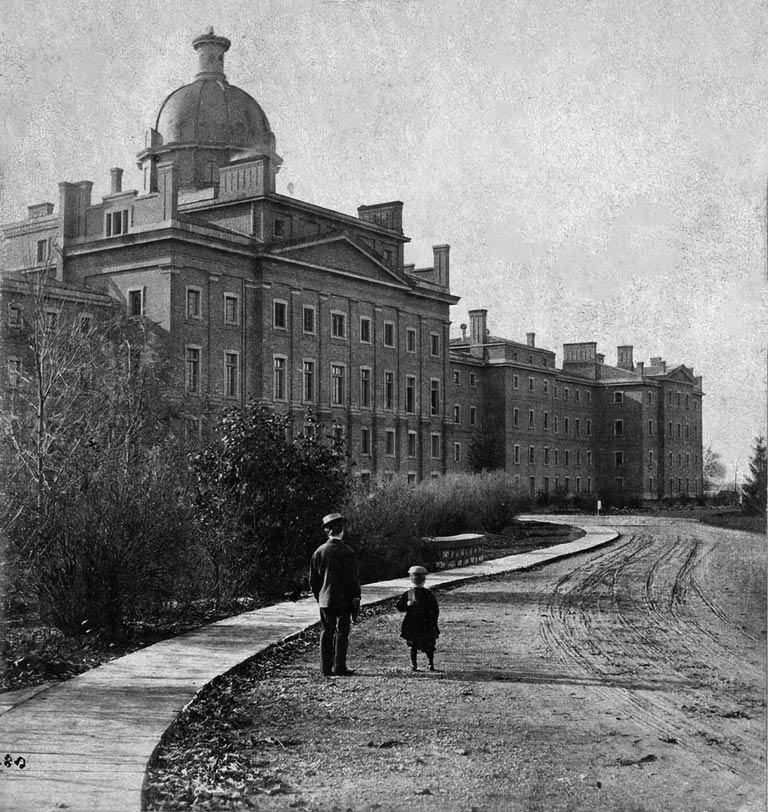

A small wooden cholera hospital opened its doors to “the insane” in 1835. It didn’t take long before the place was severely overpopulated, and it was increasingly difficult to separate men from women and the dangerous from the ill. Its only corridor served as a common area for all patients. British North America’s first purpose-built mental institution stood at the corner of Wentworth and Leinster streets in New Brunswick’s Loyalist Saint John County, with “14 lunatics in its depths and as many sick paupers upstairs,” according to 1977’s “The Development of the Lunatic Asylum in the Maritimes,” published in Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region. At the time, the concept behind this new facility — called the Provincial Lunatic Asylum — was seen as emphatically virtuous. Its opening meant the mentally ill would be cared for humanely and secured, ensuring that they weren’t left to roam around the Maritimes.

Before asylums, mental illness was a domestic issue, leaving the afflicted with their families. But caregivers who felt ill-equipped to deal with complex disorders had no choice but to send loved ones to poorhouses and jails. Those places were overcrowded and filthy, and lacking in food, heat and any kind of intervention that might help the sick, who were often kept behind bars in straitjackets and treated as though they were violent criminals. Harsh restraints and long periods of isolation were the norm.

Ontario didn’t have enough housing for the ill, so it made sense to decision-makers of the day that downtown Toronto’s old York jail be repurposed to deal with the province’s mentally ill just six years after the asylum opened in New Brunswick. By 1850, the permanent location at 999 Queen St. W. was ready, as the provincial legislature at the time said, “for the reception of insane and lunatic persons.”

Dr. Joseph Workman, then head of the institution, had a novel idea to treat patients with kindness and compassion instead of as inmates. During a visit, English-born Canadian writer Susanna Moodie, whose book Roughing It in the Bush detailed her experiences as a settler, described it as “a spacious edifice, surrounded by extensive grounds for the cultivation of fruits and vegetables … as clean as it was possible for human hands to make them” with “male patients who were so far harmless that they were allowed free use of their limbs and could be spoken to without any danger to the visitors. The female lunatics inhabited the ward to the left.… These poor creatures looked healthy and cheerful, nay, almost happy, as if they had given the world and all its cares the go-by.”

Still, most accounts of asylums weren’t so glowing. There was the filth, lack of food and questionable safety for patients, but on top of that was the stigma. The mentally ill, so went the thinking, were possessed by evil spirits or punished by God and should be hidden from society. Seeing asylums first-hand was a key reason Hincks set out to make a change.

Advertisement

Born in 1885 in St. Mary’s, Ont., Hincks graduated from the University of Toronto School of Medicine in 1907. According to the book Clarence Hincks: Mental Health Crusader by Charles G. Roland, by the time Hincks was 16, he was having “annual bouts of depression” and was interested in learning about his condition. As a young doctor who didn’t have a thriving private practice, Hincks took on a side hustle, serving as district medical inspector of schools in west Toronto. There, he observed patients who exhibited behavioural and emotional problems not unlike his own.

By 1918, at the end of the First World War, Hincks had been working in a psychiatric outpatient clinic in Toronto. He surmised that nearly every home in the country was affected by mental health problems, yet the government continued greenlighting the operation of “insane asylums.” At the same time, in his work and via his colleagues, Hincks noted soldiers were returning from overseas shellshocked, and most didn’t receive treatment to deal with the horrors of war. Continuing to witness the stigmatization of the mentally ill, Hincks reached out to Clifford W. Beers, an engineer in Connecticut who had suffered from hallucinations, delusions and manic-depressive episodes. Beers had written A Mind That Found Itself, a book documenting the physical abuse he survived in various mental institutions. Hincks had been following his work for years and knew Beers was the driving force behind the creation of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, founded in New York. The two collaborated on starting a similar association in Canada.

Hincks wasn’t alone in his desire to help — the rise in psychiatry, advocacy and public awareness meant others were willing to join the cause. In February 1918, Jessie Donalda Dunlap, a prominent philanthropist, hosted a tea at her Rosedale residence in Toronto to introduce the doctor and Beers to her influential (read rich) friends. That afternoon, a whopping $20,000 (about $430,000 today) was raised for “mental disease and deficiency.” Soon, the Governor General, the Duke of Devonshire Victor Cavendish, came aboard as patron, and the higher-ups at the Bank of Montreal, Molson Brewery and Canadian Pacific Railway signed on to support the cause. The Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene (CNCMH) launched on April 26, 1918, when members held their first official meeting. They were ready to advocate and work for change, especially after Hincks started his first major project — a national survey and report on the state of Canada’s mental institutions, for which he and psychiatric nurse Marjory Keyes travelled to Manitoba in September 1918 to visit hospitals.

In a documentary produced for the CMHA from a CBC Radio broadcast in 1965, Hincks describes his visit: “The first asylum we visited was one in Brandon. I’ll never forget it as long as I live — that asylum had 900 patients and only one doctor. He was the superintendent, and he was so busy looking after the asylum farm and signing death certificates that he had no time for the treatment of patients. There was not one trained nurse in the entire institution. The male attendants were the roughest-looking crew of men I have ever seen. And because of the number of black eyes among the patients, it was evident that they used strong-arm methods for control. Over many of the beds was heavy iron gating, and the patients beneath presented the appearance of caged wild animals.… Our resources and our facilities for giving them help are terribly inadequate.”

His recommendations were straightforward: hospitals for the mentally ill should “be regarded as being on the same plane as other hospitals.” Manitoba’s government took this to heart, providing more funding to mental health, forbidding abuse of patients and changing the names of institutions from “hospitals for the insane” to “hospitals for mental disease.”

From there, advocacy and work to change perceptions snowballed. In 1924, the CNCMH started collaborating with universities to boost funding for research and better train practitioners in mental health and psychiatry; the organization was federally recognized in 1926. Then, in 1930, the first International Congress on Mental Health was held in Washington, D.C., and attended by representatives from 53 countries, including Canada and Hincks, who was elected vice-president of the International Committee for Mental Hygiene.

In the 1930s and ’40s, Canadians were focused on wartime needs, but Hincks and his team started advocating for mental health prevention programs in workplaces and schools. Under Hincks’s leadership as general director, in 1950, CNCMH changed its name to the Canadian Mental Health Association and branches sprang up across the country. Just prior to Hincks’s death in 1964, the organization published More for the Mind, a report that was seen as the blueprint for mental health reform. In it, experts called on the federal and provincial governments to get rid of asylums in favour of supporting community services and treating mental health just like physical health. The calls to close institutions were heard, and by the middle of the decade, those overcrowded psychiatric hospitals were shuttered.

Unfortunately, the closures resulted in more negatives than positives. Poor planning meant that proper community-based services and supports weren’t readily available. The More for the Mind recommendations for sufficient funding and resources for therapy, affordable housing and social support didn’t come to fruition. Instead, discharged patients were sent to family, who were often unprepared for the emotional and financial stress. Those who didn’t have family found themselves on the streets or in shelters (an issue we still see today in many of Canada’s cities). Some ended up tangled in the criminal justice system and were incarcerated. Affordable housing and outpatient programs were either never implemented or significantly underfunded, and many of society’s most vulnerable were no better off than they were in asylums that kept them caged.

The 1970s and ’80s saw launches of crucial resources, like a centre for suicide prevention founded in Calgary, as well as supportive housing and employment programs. Then, in 1984, CMHA published its groundbreaking paper, A Framework for Support. Today in its third edition, this document highlights issues that arise when institutions are shuttered and patients are discharged without community supports.

The landscape shifted in the 1990s, in part because U.S. President George H.W. Bush and Congress designated it the “Decade of the Brain.” They noted continued study of the brain was needed to “combat the large number of debilitating neural diseases and conditions.” It was around this time when peer-support programs began sprouting up across Canada. This shift also started changing attitudes, so by the early 2000s, treatment rates were increased. More people were being diagnosed with anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, for example, and the internet started playing a role in mental illness research. This meant an even bigger push for more community-based care, funding and policy changes.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Hincks, of course, didn’t live to witness the global mental health crisis we have on our hands today. While asylums are gone in favour of hospitals like Ontario Shores, and public perception about mental health disorders has evolved, we’re still dealing with issues he faced: stigma, geographic and social disparities and inadequate funding. Mental health has recently been an even hotter topic, thanks to the pandemic and the opioid crisis. The stats are also sobering: one in five Canadians will have a mental illness in any given year, and by age 40, that increases to half of us. What’s more, 4,500 Canadians die by suicide every year and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders has increased dramatically — 3.7 million Canadians reported such disorders in 2015, while by 2022, it was more than five million. Yet, provinces and territories spend little on addressing mental health. Case in point: Ontario’s 2024-25 budget earmarked $2 billion for mental health out of an overall $85-billion health-care budget.

Still, the outlook is growing sunnier. More initiatives are being announced to improve life for those with mood and anxiety, psychotic, personality and substance-use disorders. The 9-8-8 Suicide Crisis Helpline was launched in 2023 as a cross-country 24-hour-a-day service to support people struggling, day or night, and the Public Health Agency of Canada is working on advancing the National Suicide Prevention Action Plan. There’s also the Youth Mental Health Fund, which was announced in the 2024 federal budget and will see a $500-million investment over five years for young people aged 15 to 25 (with a focus on those from underserved populations, including Indigenous Peoples and those who identify as 2SLGBTQ+) who are dealing with mental health issues. And e-mental health and virtual care is a growing sector; the Mental Health Commission of Canada developed the first strategy of its kind that looks at how apps, text, artificial intelligence and telehealth options can help Canadians from coast to coast to coast. Its recommendations are expected later this year.

CMHA continues to promote investments in mental health and well-being, as well as advocate for housing and economic security for those who need it most. Their efforts have influenced the way public perception around mental illness has evolved, with the taboo slowly crumbling. While there’s still work to do, it’s remarkable that it took a doctor dealing with his own severe depression to get this far.

Treatment Timeline

1927

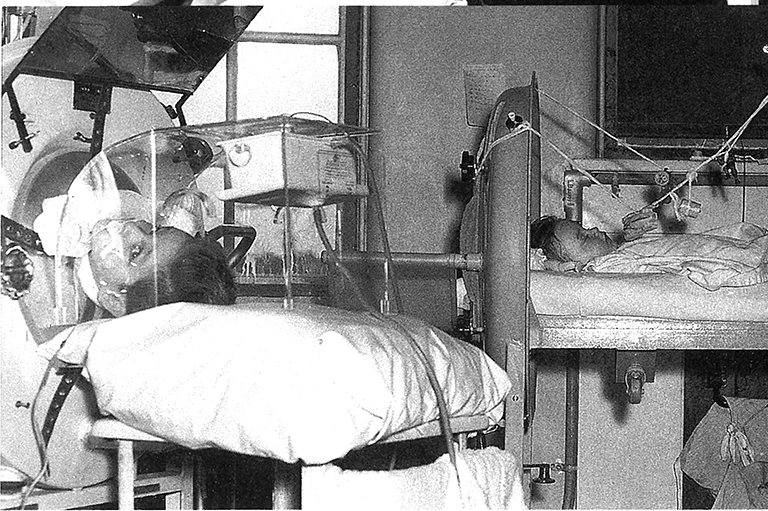

Insulin shock therapy

Doctors believed insulin fluctuations altered the brain, so they put patients into low-blood-sugar comas lasting one to four hours. Canada also used the treatment, despite a clear lack of scientific evidence supporting its efficacy and safety. Many patients (schizophrenics, mostly) ended up with brain damage.

1935

Lobotomy

This controversial surgical procedure, in which nerve pathways in the brain are severed, was popular in the 1940s and even won the Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine in 1949. It was considered radical and used in more severe cases of mania, manic depression and schizophrenia. Many lobotomized patients showed reduced agitation and tension, but others had such effects as poor focus, apathy and passivity. Some died. Survivors experienced intellectual impairment, personality changes, lack of restraint, withdrawal, chronic headaches and dementia.

1938

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Under general anesthesia, the patient has small electric currents passed through their brain, creating seizures. ECT’s portrayal in pop culture has caused lasting stigma, but it remains the gold standard for treating major depressive disorder.

1950

Antidepressants

Oral medications came on the scene in the ’50s while scientists were trying to develop a treatment for tuberculosis. The drug iproniazid (which breaks down the mood-regulating neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine) was the first that patients used and reported a change in well-being. Tricyclic antidepressants came after. The majority of people who suffer from mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety find some relief from these medications.

1960

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Developed by Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, this therapy helps patients change their thought patterns, recognize distortions in thinking and use problem-solving skills to better deal with symptoms of anxiety and depression. CBT continues to be a common recommendation from psychiatrists and therapists and is highly effective in helping treat post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, depression and eating disorders.

1980

Upgraded medications

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) debuted in the ’80s and are still popular today. The former is typically a first-line treatment for depression, while the latter is often used as a second-line treatment or for specific symptoms.

2000

Ketamine

Yale School of Medicine published the first randomized controlled trial to show ketamine’s antidepressant effects in 2000. Since then, the drug continues to be studied and used for treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and other afflictions. In Canada, ketamine is still only approved as an anesthetic; physicians and experts are pushing for Health Canada to approve it off-label for mental health.

Authorized Abuse

Mid-century interest in mental health includes shady stories. A particularly dark one is MK-Ultra, the illegal mind-control research program conducted by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from 1953 until 1964. The project’s goal? To erase the memory and brainwash people to help fight the Cold War. The experiment relied on using the mentally ill, prisoners and people with addiction — basically, “people who could not fight back,” according to one CIA officer — as test subjects, who were exposed to super-high doses of LSD and other drugs, as well as sensory deprivation, hypnosis and frequent electroshock therapy sessions.

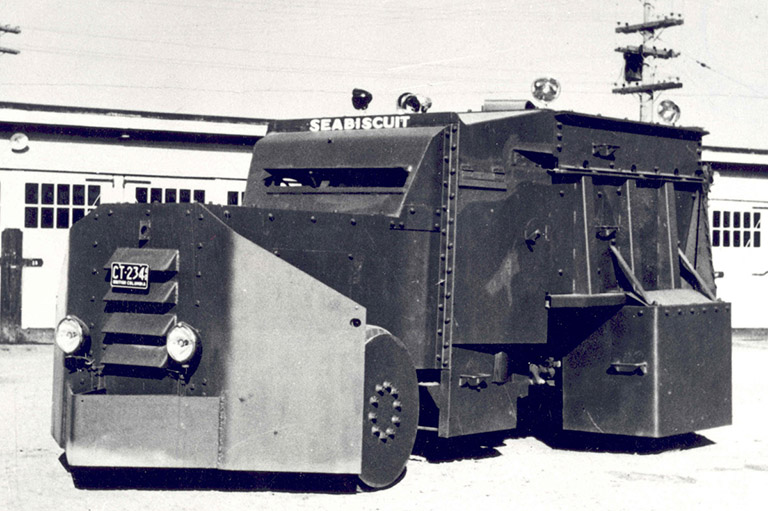

Canada played a role in MK-Ultra, too. From 1957 to 1964, psychiatric experiments believed to be funded by the CIA and the Canadian government were conducted at the Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal, a leading psychiatric hospital affiliated with McGill University. Officially listed as “an effort to find a cure for schizophrenia,” the project used drugs and other techniques to try to achieve mind control. Experiments conducted there included “psychic driving” (which forced sedated patients to listen to taped messages on a loop for up to 16 hours a day), drug-induced comas, large doses of psychotropic drugs, electroshock therapy up to 75 times the regular intensity and sensory deprivation. Patients experienced amnesia and had to relearn basic skills they had prior to treatments; their loved ones described them as “emotionally unstable and damaged.”

Difference Makers

Meet four players who have helped bring mental health to the forefront.

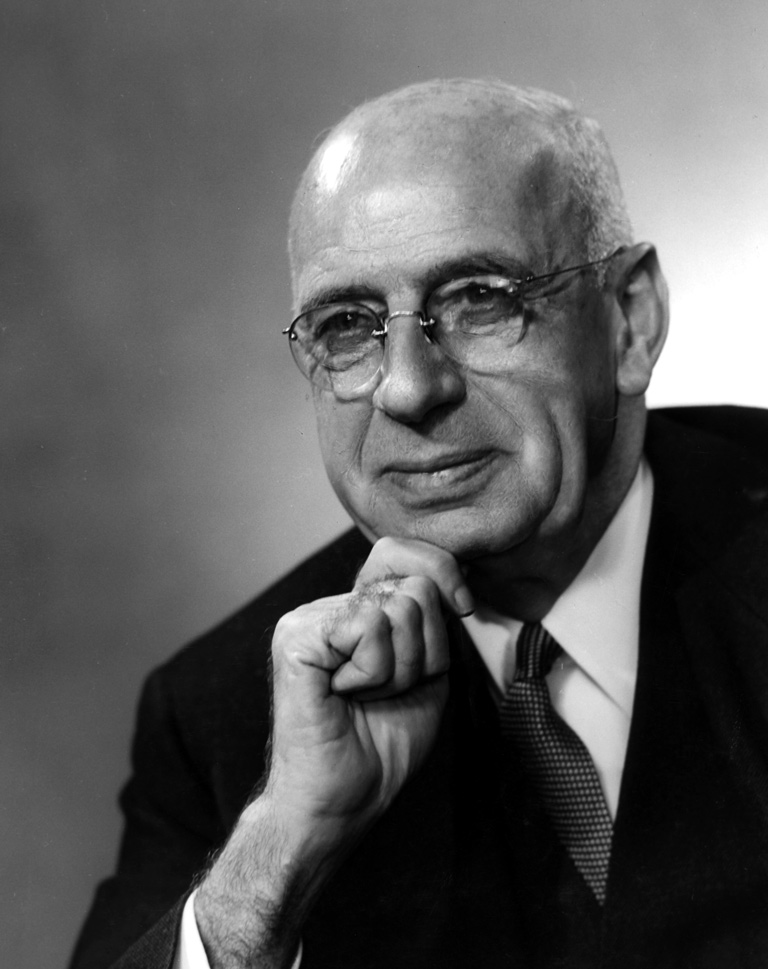

Who: Dr. Clarence Hincks

Born: April 8, 1885

Died: Dec. 17, 1964

Known for: mental-health reformer and crusader; co-founder of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene (served as secretary, then general director); director of the Canadian Mental Health Association until retirement in 1952

Who: Dr. Charles Clarke

Born: Feb. 16, 1857

Died: January 20, 1924

Known for: clinical assistant at the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto; assistant superintendent of the Hamilton Asylum and Rockwood Asylum for the Criminally Insane; superintendent of Toronto General Hospital; co-founder of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene; the name behind the Clark Institute of Psychiatry in Toronto

Who: Clifford Beers

Born: March 30, 1876

Died: July 9, 1943

Known for: American author of A Mind That Found Itself (1908); founder of the Connecticut Society for Mental Hygiene; founder of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene

Who: Dr. Brock Chisholm

Born: May 18, 1896

Died: Feb. 4, 1971

Known for: introducing mental health as part of the recruitment and management of the Canadian Army during the Second World War; federal government’s deputy minister of health; founding director-general of the World Health Organization

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement