"Queer Doings"

The first hint that George Markland’s world was about to crumble around him came in May 1838 in the form of a letter from Margaret Powell, housekeeper to the west wing of the government building in Toronto where his office was located.

She wrote in part: “Your Movements about this Building in the Evenings are watched, and have become the Subject of conjecture.”

Markland brushed aside the veiled innuendo. He wrote back saying that he occasionally met a young military man in his office because he had charge of the youth’s allowance.

Markland had given a seemingly reasonable explanation for his conduct, but the rumours did not cease, and soon he was to regret his offhanded admission.

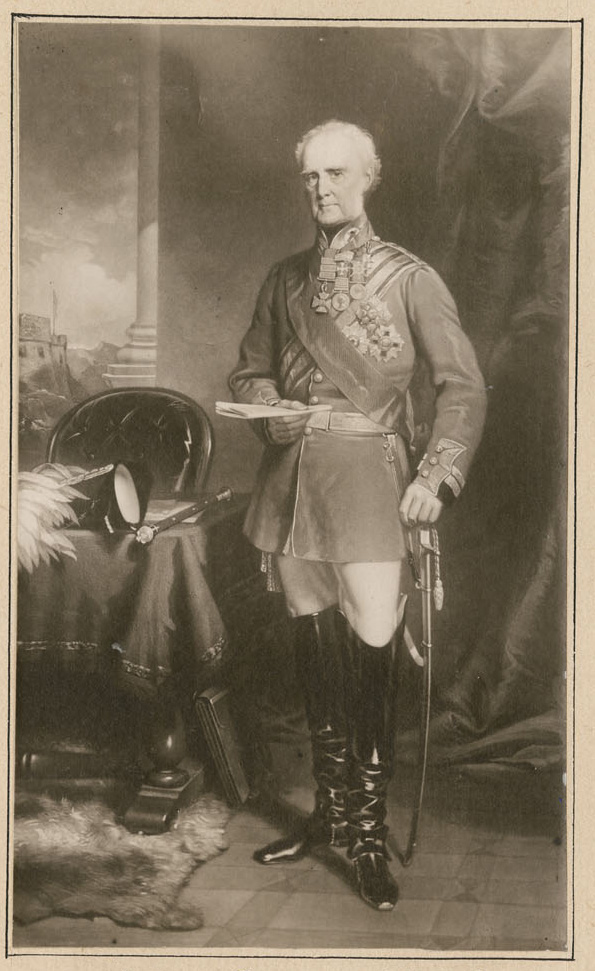

In May 1838, George Herchmer Markland was at the apex of his career. He held the influential position of inspector general of public accounts for Upper Canada and was a prominent member of the Executive Council of Lieutenant Governor Sir George Arthur.

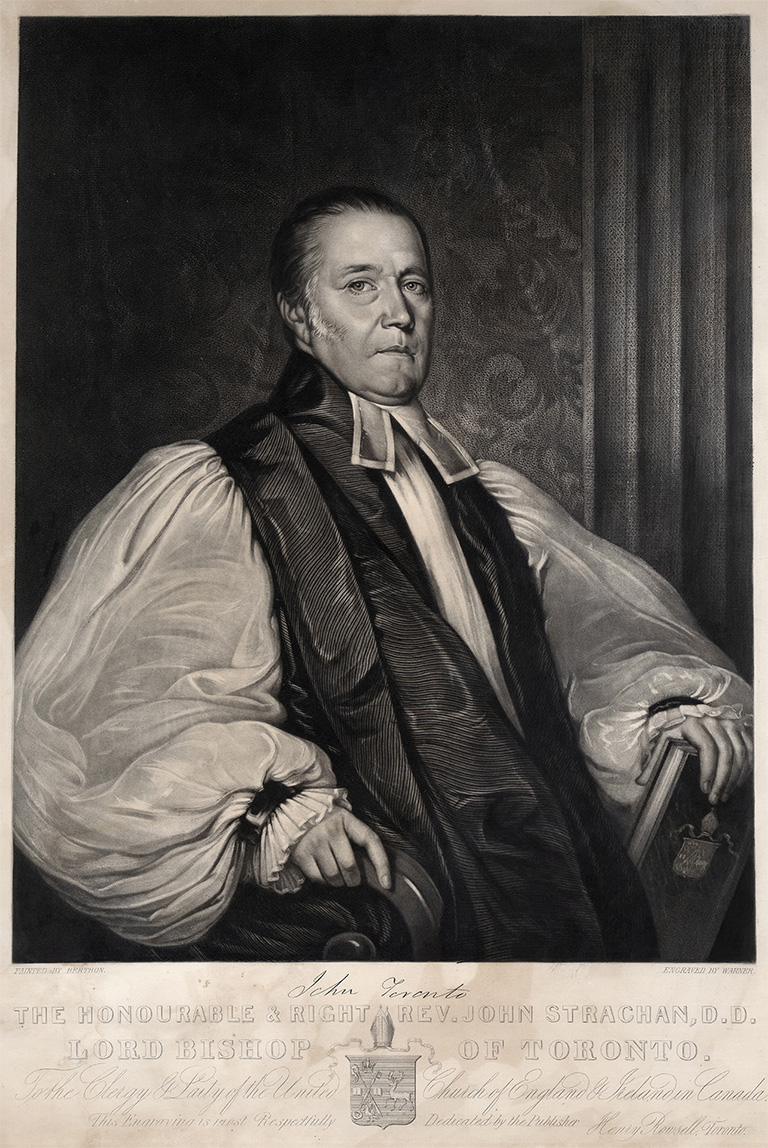

Born around 1790 in Kingston, Upper Canada, the son of a prosperous merchant, he was educated by Archdeacon John Strachan and briefly considered a career in the Anglican ministry before entering public service.

After an electoral defeat in 1820, he was appointed to the Legislative Council. His rise to power through a series of increasingly important patronage positions was steady thereafter. He was, to all appearances, diligent and efficient — a model bureaucrat, deserving the emulation and praise of his fellow officials.

One of them, future attorney general and chief justice of Upper Canada, John Beverly Robinson, had described the twenty-year-old Markland in 1810 as “a good fellow, and very friendly.”

But he added: “I prefer seeing a person at his age rather more manly and not quite so feminine either in speech or action.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

But in May 1838, George Markland’s political career and social life were about to enter eclipse. The series of events over the summer that would lead to his ultimate undoing are poorly recorded.

No newspaper covered them; only veiled, brief references appear in existing letters of contemporaries. But there was an inquiry into Markland’s behaviour.

And there are transcripts that reveal much about society’s attitudes toward homosexuality in early nineteenth-century Canada. But for them, Markland’s sudden departure from public life would have remained a mystery.

In mid-June, Markland, reacting to continuing rumours, wrote to Arthur requesting that his old teacher and patron, John Strachan, be asked to form a one-man inquiry into the innuendoes regarding his behaviour.

The lieutenant governor agreed, but decided the issue was sufficiently grave to warrant a review by the entire Executive Council. Early in July, Arthur received an anonymous letter urging Markland’s immediate removal from office lest “an everlasting stigma of disgrace fall upon the government. The writer also threatened to “direct a note to the Parliament soon.”

Markland pleaded for time to summon witnesses from distant points in his defence. On August 1, he informed Arthur that his witness, James Pearson, “a young man of the 24th Regiment, was in Toronto. He requested that the mayor take Pearson’s affidavit privately, rather than have the soldier appear in person before the Executive Council.

Arthur refused. Markland also wrote a pleading letter to Arthur stressing how he, and his father before him, had striven for over half a century “to uphold the institutions of the country” and how he had worked for almost twenty years on the legislative council and nine years on the Executive Council to further those ends.

He added: “It would seem that I am suspected of what I declare myself wholly incapable of even imagining, and I unhesitatingly assert my innocence, which I can prove. I can show, for ample testimony, that mine were acts of beneficence, not of wrong, that from an early period of my life, such acts have produced good, not evil.”

Markland stressed that he had quietly and privately helped a number of young people: “I can prove that the high and the humble have been equally objects of my beneficence, and that the occasion which has unhappily brought about all this anxiety was one equally just.”

Markland’s effort to forestall the inquiry came to nought. Whether by accident or design, Arthur did not acknowledge receipt of the letter until three o’clock on Thursday, August 2, five hours after the inquiry had begun.

The first witness, appropriately enough, was Margaret Powell, who testified that beginning in the late winter Markland had begun frequenting the Parliament Building and his office in the evenings, often accompanied by a young army drummer.

“I have seen them meet outside the building and afterwards separate — one coming to Markland’s office before the other.” she said.

At first Mrs. Powell did not connect their visits, “but from seeing them meet outside, afterwards separate and come separately into the House it appeared to me that an intimacy subsisted between them which I thought extraordinary considering the relative rank of the parties.”

On three occasions, according to Mrs. Powell, “a person in the uniform of the Band, in a white coat, came with the drummer.”

Finally, after this behaviour had been noted by both her servant and her young son, her curiosity got the better of her. On the evening of May 23, she went to Markland’s office, but found the doors locked. She stated:

I heard voices inside. ... Mr. Markland was one of the persons speaking. They spoke so low that I could not distinguish a word. I could only hear the murmur of the voices. I then heard such movements as convinced me that there was a female in the room, with whom some person was in connection. I remained there seven or eight minutes. No doubt remains upon my mind as to the nature of the noise I heard: and I was sure a female was in the room.

Mrs. Powell then waited downstairs, but it was the drummer, not a woman, who passed her “in great haste” fifteen minutes later. She did admit that she could not swear it had not been “a female in disguise.”

Immediately afterwards, Markland came down the stairs, also “in great haste,” and Mrs. Powell spoke to him: “Well Sir these are queer doings from the bottom to the top.”

Mrs. Powell also testified that when, prior to May 23, she had mentioned Markland’s peculiar evening office visits to Robert Baldwin Sullivan, another member of the Executive Council, he “made light of it and said it was all nonsense.”

But when Sullivan saw Markland’s reply to Mrs. Powell’s warning letter he decided to act. He first spoke to John Strachan as a friend of Markland, and then, finding that rumours were spreading around the city, dutifully reported the situation to the lieutenant governor.

Exactly how the rumours spread, or whether they were but the rekindling of earlier stories about Markland, will probably never be known.

However, it does appear that it was not so much Mrs. Powell’s charges themselves, as the evidence in Markland’s own handwriting that he had had young male visitors at his office after hours, that had set the inquiry into motion.

The inquiry’s second witness, Hannah Pike, was Mrs. Powell’s servant and helped with the chores in the Parliament Building. She corroborated much of the evidence of her mistress concerning Markland’s evening visitors, including the point that he locked his office doors during such visits.

She testified that she had seen a drummer from the Twenty-fourth Regiment other than the one noted by her and Mrs. Powell visiting Markland, and she added the names of two others — Henry Hughes, an eighteen-year-old labourer from Strachan’s household, and her cousin, John Brown, a private in the Queen’s Rangers.

Brown told the inquiry he met Markland several times. Though he commented on “the familiar manner of his walks with me and leaning on my arm,” he was quick to add that Markland “never made use of improper language in my company.”

Friday’s first witness, Richard Hull Thornhill, first clerk in the Crown Lands Office, testified that he had gone to see Mrs. Powell at Markland’s request.

He had urged her to declare that “she had not actually seen anything”; that “any reports she had originated were founded merely on suspicion”; and that “all the facts stated by her did not amount to positive proof of Mr. Markland’s criminality and would not be considered as doing so in a Court of Justice. (While the Executive Council had many powers of inquiry, it was not a court of law.)

However, his testimony supported Mrs. Powell as a reliable witness: He said he knew her well and could not see what would motivate her to make a false accusation.

That day, Markland’s witness, James Pearson, a fifer in the band of the Twenty-fourth Regiment of Foot, appeared. Though Markland intended Pearson’s testimony to refute Mrs. Powell’s charges, the young soldier, though sympathetic, did not perform as Markland hoped.

It was clear he had no desire to share the opprobrium directed at the inspector general. Much of his testimony was ambivalent. He said he first heard of Markland from a Sergeant Jones who “had mentioned to me that Mr. Markland had expressed his willingness to purchase my discharge [from the army].”*

He admitted to meeting Markland on many occasions in his office, but he said he never stayed for more than fifteen minutes, during which they discussed his desire to leave his regiment and the possibility of Markland purchasing his dis charge.

As to whether Markland took his arm during a walk on the wharf or locked the door during office visits, he said he could not remember. Nor could he recall if he had been in Markland’s office on the evening of May 23, when Mrs. Powell allegedly heard noises.

Some of his testimony actually proved harmful to Markland’s case. He stated that Markland “never received any money for me and he never gave me any,” which directly contradicted Markland’s letter to Mrs. Powell saying he had charge of Pearson’s allowance.

And he also introduced a new figure, “a young man named Monaghan of the Band,” for whom Markland had also offered to purchase his discharge.

Pearson described him as “younger than me, he plays a clarinet in the Band. Monaghan has light brown hair. He always wore a white coat — the uniform of the Band.”

There was also a discrepancy over a letter from Markland, which Pearson said he received in Bytown (Ottawa) through an intermediary, William Morrow. Pearson claimed a second letter arrived from Markland while Morrow was in Bytown that asked for the return of the first.

Morrow, however, claimed there was only one letter between Pearson and Markland, delivered earlier, and he had gone to Bytown for the sole purpose of getting it back. Either Pearson or Morrow was lying under oath.

If Markland’s original letter contained material reflecting on his sexual preferences, Pearson would have wished to indicate bed returned it immediately.

Markland’s friend Morrow, on the other hand, would have wanted to show that Pearson, by keeping the letter a long time, couldn’t have felt its contents warranted its immediate return.

Saturday’s last witness was law student Frederick Creighton Muttlebury, who had first met Markland in Toronto when he was eighteen. Markland had convinced him to study law in Toronto rather than become a clerk in Quebec and offered him money to do so.

Though he never boarded with Markland (he boarded outside the city), he did dine with him “about three times a week” for about a year. But he broke off his relationship with the inspector general.

Markland, according to Muttlebury, began to look at him in a “kind of smirking way I did not like” and would hold his hand.

“On one occasion,” Muttlebury testified, “I was dining with Mr Markland alone when I was much ashamed at Mr. Markland making the following observation: ‘You have the most perfect figure of any one in town. Several people have remarked it.’”

Yet, said the agile law student, excusing himself from any possible tinge of mutual guilt, he had not at the time suspected Markland of criminal intentions. Said he “I had scarcely any conception at the time of the possibility of a crime of the nature which afterward suggested itself to me.”

But the most extraordinary aspect of Muttlebury’s testimony was his statement that two years earlier he had shown improper letters he had received from Markland to the then lieutenant governor, Sir John Colborne, who was curious about why he had broken off with Markland.

Colborne informed Chief Justice John Beverley Robinson of the transaction and recommended Muttlebury’s mother show the letters to another member of the Executive Council. He told Muttlebury he was correct to end the relationship.

Muttlebury’s final comment was that Markland “never attempted or proposed in the remotest manner anything improper or criminal to me,” and added to protect himself: “if he had done so, I should not have contented myself with withdrawing from his acquaintance and protection.”

Despite the ambiguity and denials, the innuendo proved damaging. On Sunday John Macaulay, Arthur’s secretary; wrote to his wife: “The investigation of Mr. Markland’s case is now going on. It is rumored that he cannot succeed in clearing the matter up.”

On Monday, August 6, Henry Hughes, who had worked in John Strachan’s household for three years, testified that he had joined Markland in his office on two evenings.

He admitted “it did appear strange to me to be asked to [his] office,” but added that Markland’s “conversation always was relating to my affairs. ... [He] never said or proposed any thing improper to me, and he gave me good advice as to my conduct.”

Margaret Powell returned next to testify that James Pearson was not the person she had seen visiting Markland. The man she saw wore the same uniform but was stouter and had lighter hair.

Hannah Pike gave essentially the same evidence. She said she had only named Pearson because he had fit the description she had given to another member of Twenty-fourth Regiment.

As the Executive Council adjourned for the day, its members must have realized that Markland had known Pearson was not the man whom Mrs. Powell and Hannah Pike claimed to have seen. It is the only logical explanation for Markland’s effort to keep Pearson from appearing in person at the inquiry.

Robert Baldwin Sullivan immediately wrote Markland asking for the name of the light-complexioned man that Pearson had introduced in Friday’s testimony.

Though his reply has not been preserved, Markland apparently corroborated Pearson’s testimony. He mentioned William Monaghan as possibly fitting the description.

The only witness heard on Tuesday, August 7, and the last whose testimony is available, was a Toronto merchant, Henry Stewart, who testified that in 1835 during an evening walk with his younger brother John,

“Markland put his hand in an indecent manner on my brother’s person.”

The Executive Council ordered that John Stewart be requested to appear “with us little delay as possible.” It then adjourned and never met again to discuss the Markland affair.

John Stewart apparently did come to Toronto, for his travel expenses of £4.12.0 are listed in the council minutes some months later, but his testimony, if it was given, has not been preserved.

Nonetheless, whether Stewart’s testimony was incriminating or whether the allegations proved overwhelming, Markland was presumed guilty. On August 28, his career in shambles, Markland wrote a resignation letter to Arthur’s secretary. In return, the inquiry was dropped.

Markland returned to Kingston to live in virtual isolation. He never again held any public office. However, his problems did not end with his virtual banishment.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In 1841 a legislative committee discovered that, as treasurer of the provincial school lands fund, he was in default almost £5,000 for the period 1831–1838.

He did not deny responsibility for the deficit and reimbursed the government by occasional payments and provisions in his will.

He may have been guilty of no more than careless accounting, a common fault among nineteenth-century Canadian officials.

In the mid-1840s, Markland barely escaped civil suit by the Council of King’s College for his role in using college funds in 1831 for the erection of Upper Canada College.

Strachan intervened on his behalf and convinced the council that Markland had merely been acting on the orders of Sir John Colborne.

George Markland lived on in obscurity in Kingston until his death in 1862, twenty-four years after his resignation. Much of his life remains a mystery.

He was, for example, married; an obituary of his wife appeared in an 1847 newspaper. But who she was, whether they were married in 1838, or if they had children are not known.

Today, only a few of Markland’s letters remain, scattered in the correspondence of his friends and associates.

The passing of his Family Compact peers elicited glowing eulogies from reform and conservative newspapers alike, but Markland’s death was noted in the Kingston Daily British Whig and in the Toronto Globe by identical two-line obituaries.

If his contemporaries attempted to forget Markland, his career, and its eclipse, they were almost completely successful.

But if little can be said with certainty about Markland as an individual, it is possible to speculate upon the views of his fellows toward homosexuality.

On first glance the Markland case would seem to indicate that no clandestine homosexual community or group existed in Toronto in the 1830s, only a single lonely individual bumbling from one unhappy encounter to another.

A second glance indicates otherwise. Evidence suggests that Markland, about forty-eight in 1838, preferred brief sexual encounters with young men. usually of a lower social class.

Toronto, a colonial capital and garrison town, saw a steady stream of such young men making their mark in the world, some of whom were willing to trade sexual favours for advantage of one kind or another — often the purchase of a discharge from the British army.

In this, he was aided by Sergeant Jones. If Markland was, as he claimed, merely a private patron who enjoyed helping others, then Sergeant Jones can be seen in the same light. But it does seem strange that a career soldier would actively work to deplete the forces under his command in a period of border raids out of a sense of philanthropy.

If Markland was guilty of homosexual activity, then the sergeant was guilty of procuring. Markland’s evening walks near the Parliament Building and the number of his encounters suggest that society in 1838 differed little, if any, from today’s.

As for the witnesses, they were either antagonistic or sympathetic. The former, such as Mrs. Powell, felt simply that it was her duty to expose what she understood as his criminal behaviour.

The motivation of the witnesses sympathetic to Markland was more complex. Time and again they offered bits of testimony that could be construed as incriminating, but always stressed that Markland never proposed anything improper to them as individuals.

Each was torn between the desire to support Markland’s claim of innocence, and the overwhelming spectre of being associated with Markland if he were found guilty. Only Henry Hughes, the ex-servant of John Strachan, unreservedly supported Markland’s case.

The rest made certain that if Markland fell, they would not go with him; at worst they would be viewed as having been naive and used by the inspector general. The fear of the sympathetic witnesses is almost tangible and it gives one some sense of the severity of the stigma society attached to homosexuality in Toronto in the 1830s.

The attitudes of other public figures toward Markland in particular, and toward homosexuality in general, are more difficult to assess. If, as Muttlebury testified, definite evidence of Markland’s sexual proclivities was available in 1836, why did the inquiry not occur until 1838?

Arthur, a career officer in the British Army, appears to have pressed Markland relentlessly, refusing his every effort to forestall or avoid the inquiry, while his predecessor, Sir John Colborne, likewise a professional soldier and aware of Markland’s sexual preference, took no official action.

There are two possible reasons: Between 1836 and 1838 stood the Rebellion of 1837. Arthur may have sacrificed Markland in the aftermath of the Rebellion to show the populace that the British government was as capable of punishing Tories as it had been of suppressing rebels.

Arthur may also have insisted on a speedy and complete inquiry because rumours of Markland’s illicit activities, contained during Colborne’s tenure, were becoming widespread.

This suggests that Upper Canada’s high-ranking government officers didn’t object as much to Markland’s alleged homosexuality as they did to its becoming publicly known. In short, as long as homosexuals weren’t doing it in the street and frightening the horses, then it could be tacitly ignored.

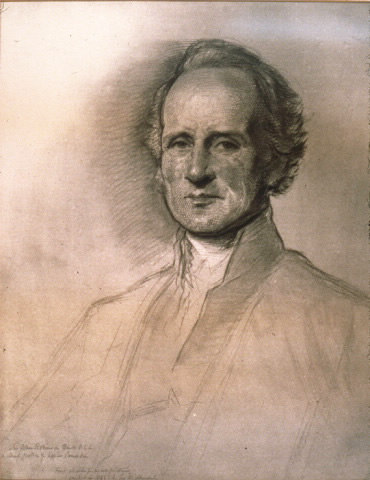

John Strachan’s attitude toward Markland is representative. A keen observer and shrewd judge of people, Strachan appears neither to have reacted to insinuations against his former pupil nor to have curtailed the development of a relationship between Markland and Henry Hughes.

However, in the aftermath of the scandal, Strachan distanced himself from his protégé. His papers contain few references to Markland, either he or his literary executors culled his files before they were presented to the archives.

It would appear, then, that Upper Canada’s educated governing class was more tolerant of homosexuality in practice than the penal code — which imposed death for sodomy — would suggest.

Indeed, Markland’s peers could be seen to have exhibited some mercy. He could have been turned over to the criminal courts for prosecution of a felony, but he was not. Instead, he was allowed to retire, in comfort, if in disgrace. And then to virtually disappear from history.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.