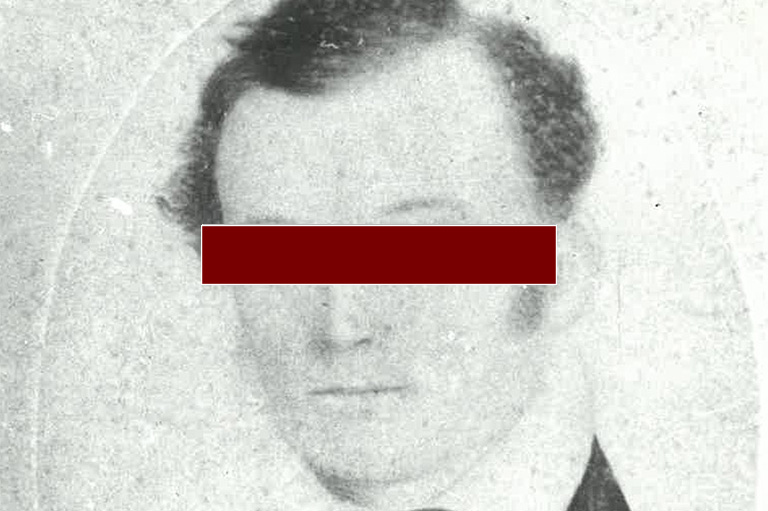

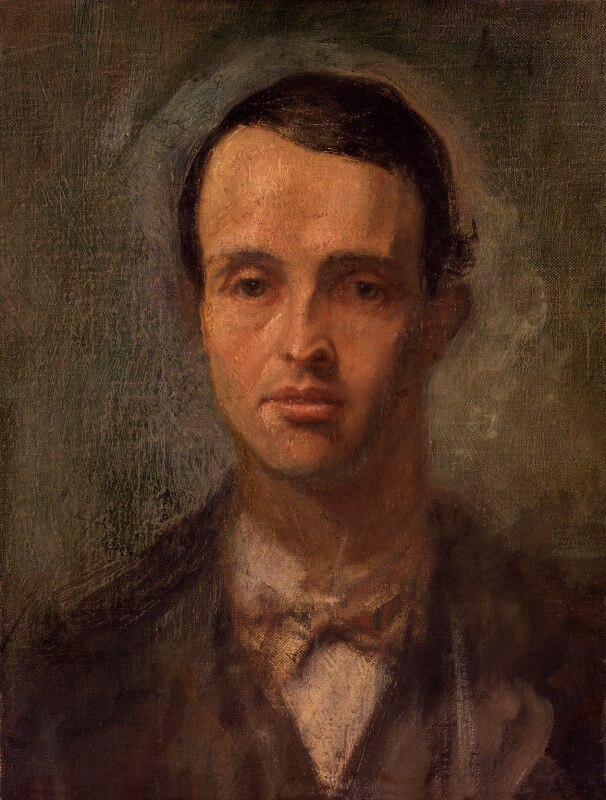

A Portrait of Robert Ross

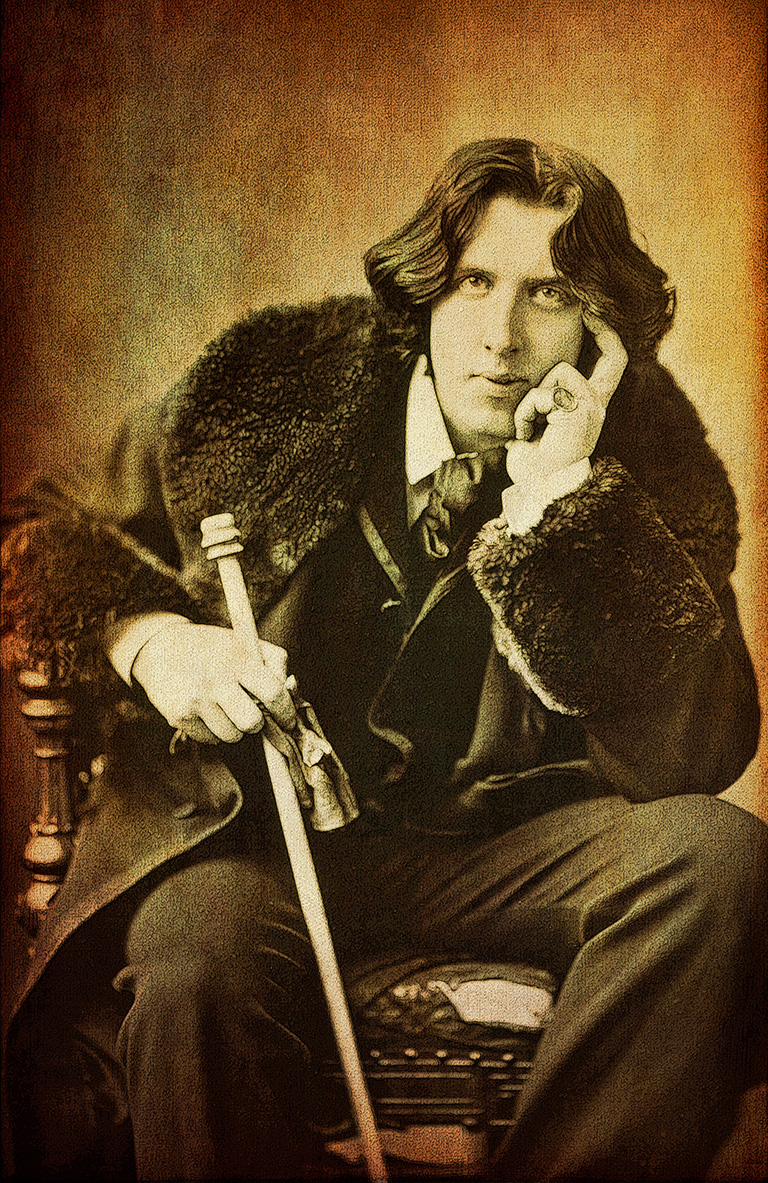

On December 3, 1900, Oscar Wilde — who would later be called the greatest wit and dramatist of the nineteenth century — was buried at Bagneux, France.

There were three principal mourners — Lord Alfred Douglas, Reginald Turner, and a man who had proven, and would continue to prove, to be Wilde’s closest and most devoted friend. His name was Robert Baldwin Ross.

The child of a privileged Toronto family, he was the grandson of Robert Baldwin, appointed solicitor general of Upper Canada in 1840 and prime minister in 1848, and the son of John Ross, who was appointed solicitor general for Canada West in 1851.

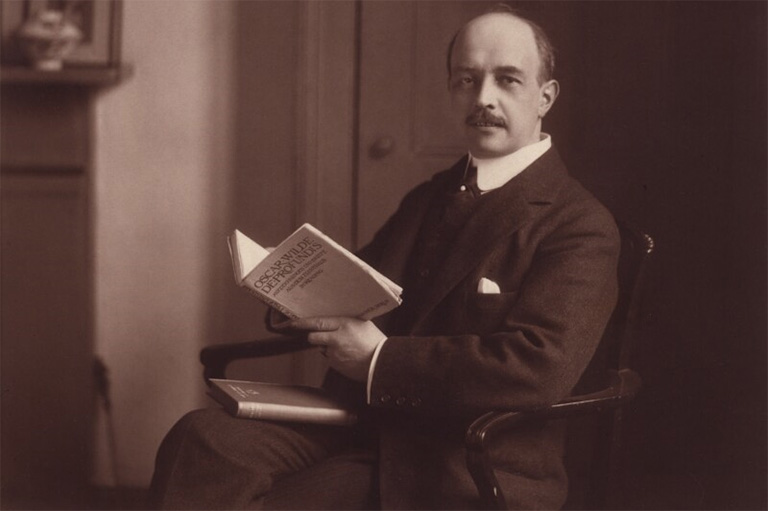

Within two decades of Wilde’s death, Robert Baldwin Ross himself would be dead, but during that period he devoted his life to putting Wilde’s plays back on the stage, his books back in the shops, and his royalties into the hands of creditors to clear his bankruptcy debts.

He also arranged the posthumous publication of De Profundis, Wilde’s epic, open letter to Douglas, the young man with whom he had become infatuated and who had brought about his downfall. Finally, Ross’s most ambitious undertaking was to move his friend’s remains from their insignificant suburban gravesite to a prestigious position among his cultural peers at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Thanks to Ross, the man ostracized by British society for his sexual conduct regained his reputation as a literary genius.

Robert Baldwin Ross was born to John and Eliza Ross in France, May 26, 1869, the youngest of four boys and three girls. Four years earlier, his parents had travelled to France from Toronto, where they had taken residence in Tours.

Eliza, who was in poor health, found the climate of central France idyllic, and John, who had business interests in England, was able to commute across the Channel. An Irish lawyer, John had married Eliza in 1851 in Toronto’s St. James Cathedral, served as solicitor general, and had become a respected advisor to the British financial community.

Though his legal practice had been in Belleville, Ontario, he had moved to Toronto at his wife’s insistence when his father-in-law’s health began to deteriorate, here, he and Eliza built an estate called Earlscourt, where they were once host to Edward XII, then Prince of Wales.

When the Rosses returned to Canada with infant Robert, they reentered Toronto society, but their pleasure in its social life was shortlived. In 1871 John Ross died. In his will, he specified that his children be educated in England. Eliza sold Earlscourt and crossed the Atlantic once again, installing her brood in Phillimore Gardens, a fashionable London thoroughfare just west of Kensington Palace.

The Rosses were well aware of Oscar Wilde. A household name in the columns of London newspapers, Wilde also had links with many of Eliza’s Canadian friends and relatives.

The Irish playwright and social arbiter was acquainted with Canada’s fourth governor general, the Marquis of Lome, his wife Princess Louise, his sister Lady Frances Balfour, and his sister-in-law Lady Archibald Campbell. (During Wilde’s tenure as editor of The Woman’s World, “Lady Archie” was one of the first people he contacted to be a contributor.)

Wilde had visited Ottawa during his 1882 North American lecture tour, and though disappointed not to be received at Rideau Hall — Princess Louise was in London and her husband occupied with state business — he was wined and dined by private citizens.

Among them was painter Frances Richards, who was a close friend of the Ross household. Richards painted a portrait of Robert and his eldest brother, Alexander, and also produced a portrait of Wilde himself. (It has been said that Wilde remarked how unfair it was that the image would remain young while he grew old, predicting the plot for his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray.)

When Frances first visited the U.K., she arrived bearing a letter of introduction from Wilde to artist James McNeill Whistler, whose complex relationship with Wilde led to years of printed exchanges in London periodicals. Whistler was a companion of Lady Archibald, who, in turn was a friend of James Rennell Rodd, one of Wilde’s literary protégés. Rodd’s book of poems, Songs in the South, published in 1880, was inscribed with a dedication to Wilde. Relationships were tangled.

Young Ross grew up hearing of Wilde’s celebrity. When he was seventeen and preparing for entrance exams for King’s College, Cambridge, with an Oxford tutor, he was introduced to Wilde, who, as a graduate of Magdalene College, Oxford, was visiting his old school.

The teenaged Ross was thrilled to meet the writer. He was already an admirer and had endured a beating at school rather than give up reading Wilde’s florid poetry. He also imitated Wilde’s shoulder-length hairstyle, which was part of the image of the aesthetic movement that Wilde championed.

Ross’s own literary interests came early. At Cambridge, he cofounded a student magazine called The Gadfly. He also wrote for Granta, a journal that enjoys a high-profile existence to this day.

At the end of his first year, Ross told his mother that he was homosexual and would make no secret of it.

Eliza was horrified. The Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 had made acts of “gross indecency” between males punishable by up to two years imprisonment “with or without hard labour.”

Alexander, who had been named Robert’s guardian, promptly cut off his younger brother’s funding at Cambridge, and Robert fled to their paternal grandparents’ home in Scotland where he received a more tolerant welcome.

He joined the Edinburgh-based publication The Scots Observer as a journalist and later managed a private art gallery. However, like many young men who wanted to be at the epicentre of Victorian life, Robert finally returned to London to pursue a career as an art critic. He headed for Chelsea.

Originally a riverside hamlet famous for its flower-filled gardens, Chelsea had merged with the capital and become a developer’s dream. By the time Robert arrived, it was the fashionable address for London bohemians.

Oscar Wilde lived at 16 Tite Street (now renumbered 34); his mother Lady Wilde, who wrote poetry under the pen name Speranza, lived on Oakley Street.

Close neighbours included designer Edward Godwin (who decorated Wilde’s home after his marriage to Constance Lloyd), actress Ellen Terry, who became Godwin’s second wife, James Whistler, and Frances Richards, who maintained a studio just round the corner from the Godwins. The smart addresses of Chelsea’s artists and writers provided the social tapestry of Ross’s adult life.

According to The Wilde Album, written by Merlin Holland, Wilde’s grandson, Ross became a “paying guest” in the Tite Street household. This was probably a short-term arrangement until the young man gained a foothold in the city.

Publisher and journalist Frank Harris, sympathetic friend of Wilde’s (despite being, according to his memoirs, a rampant lady-killer), once asked the writer who had seduced him. Said Wilde, “It was little Robbie!” Later, Ross denied a physical encounter but added ingenuously that, had it taken place, “I wouldn’t have minded.”

Reginald Turner, barrister-turned-author of lightweight novels, claimed to have been told a similar story: Ross introduced Wilde to same-sex relations, but not much happened between them.

In any event, what physical involvement there may have been between Ross and Wilde disappeared as quickly as it came, and they settled into a platonic friendship that lasted for the rest of the author’s life.

We can picture long lunches at the Café Royal, companionable visits to the Royal Academy of Art, exchanged dinner invitations, complimentary theatre tickets, and family evenings at the Tite Street household (now increased by two sons — Cyril and Vyvyan).

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In De Profundis, Wilde mentions — recollecting years of profligate disregard for money — that the nicest supper he ever had was with Robert in a Soho cafe with a “fixed price” meal of a few shillings.

Ross admired Wilde’s talent and charm. Wilde found Ross trustworthy and a witty conversationalist. (The fact that he was a member of a prominent Canadian family didn’t hurt.) The two men enjoyed each other’s company and, not least, a shared Irish heritage in an English society. Nothing was at stake.

But the test of their friendship was to come.

Much has been written about Oscar Wilde’s trials. In brief, the author was besotted by the friendship of Lord Alfred Douglas, son of the Marquis of Queensberry. When Queensberry accused Wilde of corrupting his son in 1895, Wilde took him to court for slander, but lost, withdrawing the charge when defence witnesses proved damaging.

Wilde was then tried under the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, but a mistrial was declared when the jury couldn’t agree on a verdict. A subsequent trial found him guilty. These were followed by another, less-publicized court appearance for bankruptcy.

During this time, Ross’s loyalty was stretched to its limit. He had referred Wilde to his own solicitor, Charles Humphreys, and must have felt greatly embarrassed when it turned out the playwright had lied to both of them.

Ross was not naive. He was well aware of Wilde’s relationship with Douglas, but the seamier stuff of the trials — male brothels, teenaged boys in hotel rooms — had unnerved him.

Following the collapse of the suit against Queensberry, he joined Wilde at the Cadogan Hotel, Sloane Street, until police arrived with a warrant for Wilde’s arrest. The court itself, in a burst of feeling that the whole thing had got out of hand, postponed the arrest to allow Wilde time to catch a boat train out of the country.

Ross begged his friend to take advantage of the delay, but he wouldn’t budge. (His attitude would later be blamed on Irish fatalism and a masochistic urge to watch his own destruction.) Wilde was taken to Bow Street Police Station.

Ross hired a cab and travelled to Tite Street to apprise Constance and gather Wilde’s clothes. Arriving at Bow Street, he was refused entry. The prisoner was prohibited from receiving personal effects. Ross returned once more to Tite Street where the butler broke the lock on the study door. (By this time Constance and her children had fled to relatives, correctly surmising that the house would shortly be under siege.)

He stripped the study of all personal papers, but he had neither time nor resources to pack the room’s splendid collection of first editions, books autographed by all the great English and French writers of the period. These disappeared during the bailiff’s auction of Wilde’s family property.

At this point Ross had crossed the city four times in a single day through heavy, horse-driven traffic. He was devastated. Tired and helpless, he went home to his mother.

Eliza Ross had never stopped caring for her youngest child, and she pleaded with him, after he had had a decent meal and a good night’s sleep, to leave the country himself. Hundreds of “effeminate” London gentlemen were suddenly taking off for Calais, she told him. Ross wasn’t happy deserting his friend, but Eliza promised to contribute £500 towards Wilde’s legal expenses if Robert took her advice. That day she sent him off to France, breathing a sigh of relief.

Eliza had good cause to worry. Robert’s name had popped up in several newspaper accounts documenting Wilde’s activities. As a result, some of London’s most prestigious clubs had revoked his membership, and a number of influential friends had broken off relations.

Ross stayed in France over the next year, returning to London whenever he felt duty called. Wilde’s emotionally trying bankruptcy was one such occasion.

The playwright’s court appearance in September 1895 culminated with an itemized account of personal expenses throughout his association with Douglas. It appeared Wilde had squandered more than £3,500 entertaining his aristocratic friend. Rented vacation homes, trips to Europe and North Africa, gifts of jewellery, and the ever-present bottles of vintage champagne at the Café Royal were humiliating reminders of a life led to excess.

As Wilde was taken from his hearing, Ross — who had waited for hours in the corridors of the courthouse — stepped out from the jeering crowd and solemnly tipped his hat to his friend. “Men,” said Wilde later, “have gone to heaven for less.”

Wilde begged Ross for news of his sons. Constance had settled in Europe and changed the boys’ surname to Holland (a family name from the Lloyd side of the marriage). Ross did manage to obtain two photographs of Cyril and Vyvyan taken in Heidelberg. He also found some letters they had written to their father before the fatal year of his trial and imprisonment.

Wilde spent two years in jail. Released in 1897, he spent the last three years of his life on the Continent.

To Ross, who praised the play, Wilde — by then released from jail and living cheerlessly on the Continent — wrote: “There are two ways of disliking my plays. One is to dislike them, the other is to like ‘Earnest.’ To prove to posterity what a bad critic you are I shall dedicate the play to you.”

When he died in Paris November 30, 1900, he left no will. He had no money to leave. But there remained the legacy of his literary accomplishments, among them his plays, Lady Windermere’s Fan, An Ideal Husband, The Importance of Being Earnest, A Woman of No Importance; his novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray; and his poetry, including The Ballad of Beading Gaol.

Constance had died in 1898; Wilde’s sons were too young to handle their father’s estate; and his brother William too ineffectual.

Ross took it upon himself to seek official approval for his own appointment as the writer’s literary executor. It took courage — during those first years following the funeral England was still loath to handle Wilde material — but he achieved his aim, and negotiated translations throughout continental Europe.

The German edition of Wilde’s work included an introduction Ross wrote himself. He also dedicated various publications to supporters he thought Wilde would have wanted to recognize, and arranged an American production of the play Salomé, starring Maud Allen, while Britain was still legally bound to prohibit biblical characters on stage.

In 1907, when Helen Carew of Hans Place, London, learned that Wilde’s youngest son Vyvyan was back in England, she invited him to dinner. Ross dedicated the first, shortened version of De Profundis to Carew because it was she who pledged money for the final gravesite in Père Lachaise Cemetery, as well as for the monument by sculptor Jacob Epstein that identities it.

Following that pleasant evening, she arranged a second dinner that included Ross, Reginald Turner, and writer and caricaturist Max Beerbohm. It was the first time in twelve years that Ross had seen Vyvyan and the first time the son had spoken with three of his father’s oldest friends. In his own autobiography, Son of Oscar Wilde, Holland says that from the moment he met Ross he knew he had a true friend.

Ross introduced Vyvyan to a number of Wilde’s contemporaries so the young man might form a more positive view of his father’s talent and personality.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

One friend was Ada Leverson, whom Wilde called the “Sphinx.” When virtually every hotel in London refused Wilde lodgings, Ada had welcomed him as a houseguest.

Another introduction was made to Adela Schuster, a woman who didn’t know Wilde well but gave £1,000 towards his legal defence simply because she loved his work.

Robert knew Wilde regretted never having thanked Schuster, so he dedicated The Duchess of Padua to her when the play was printed in the first collected edition in 1908.

When Vyvyan turned twenty-one, not a single member of his extended family acknowledged his coming of age. However, Ross orchestrated a birthday party at his own home, 15 Vicarage Gardens, Kensington, which he shared with his companion, translator More Adey.

The fourteen guests included Adey, Reginald Turner, American expatriate Henry James, writer Ronald Firbank — and Vyvyan’s elder brother Cyril, whose feelings toward his father were less generous than Vyvyan’s. (Cyril never married and died in action during World War I).

On December 1, 1908, a magnificent dinner with more than a hundred and sixty guests was given for Robert Ross. Having laboured to become Wilde’s executor, extracting royalties from every production company in Europe, he finally achieved his goal — the English publication of Wilde’s complete works in fourteen volumes. The evening was a tremendous honour and included virtually every famous author in England.

The following year, Ross took Vyvyan with him to attend the removal of Wilde’s remains from Bagneux to Père Lachaise. He had ordered a custom-built coffin, but due to French red tape it could not be used.

The coffin provided was plain oak with a plaque on the lid that read “Oscard Wilde.” When Ross saw the extraneous “d,” he had an uncharacteristic tantrum and only calmed down when the undertaker removed the letter.

He was also shaken when Wilde’s remains were exposed during the exchange of coffins. Ross had requested lime to speed up deterioration. In fact, a preservative had been used.

Throughout his life spent salvaging Wilde’s career, Ross still had to earn a living. He was a director of the Carfax Callery in London, art critic for The Morning Post, and trustee for the Tate Gallery. He was also an advisor to several overseas galleries.

He was a generous man. When he was given a testimonial dinner to raise funds for litigation expenses generated by Lord Alfred Douglas’s continually harassing him, he paid his own bills and directed the money to a Robert Ross Memorial Prize at the Slade School of Fine Art. More than three hundred people subscribed, led by George Bernard Shaw.

The Ross Memorial Prize is still presented at the Slade’s graduation ceremonies. (Cash value is £135, a small amount by today’s standards, but a welcome gift when one could subsist on £200 a year.)

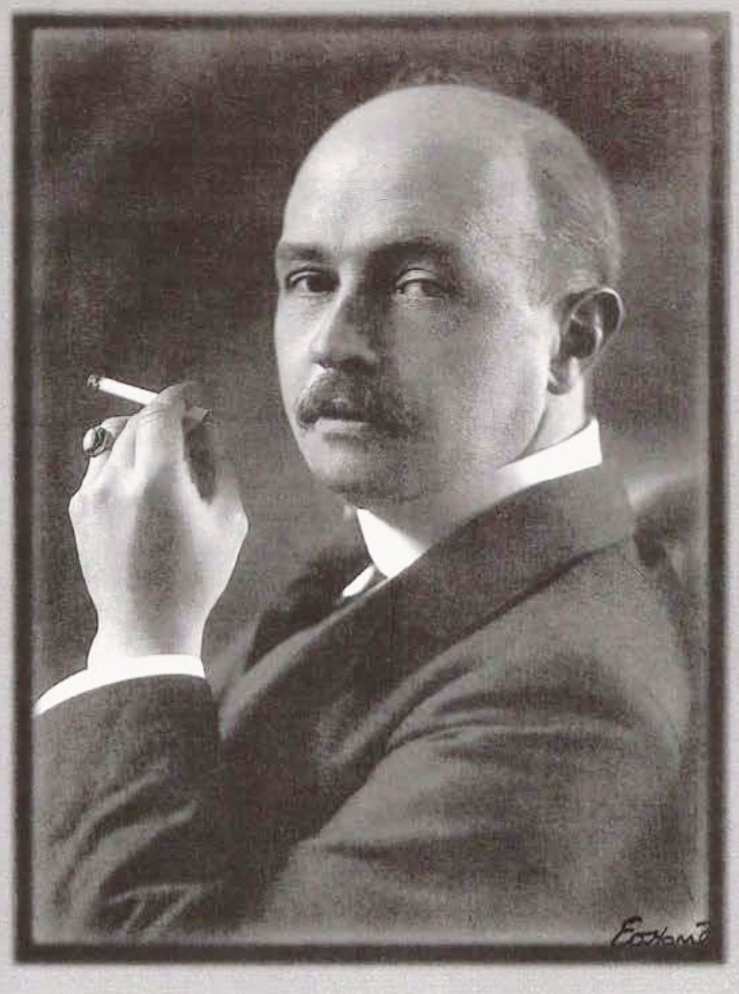

Ross was never a great businessman, nor a significant figure in the art world, but he had a solid career and made many friends. Author Sheridan Morley says Ross was “a born personal assistant,” a second-in-command. He was polite and soft-spoken, known for a sense of humour and lack of vanity. Neither was he famous.

It was only through his father’s dying wish and his mother’s emigration that he met Wilde, and crossed paths with the most outstanding talents of the nineteenth century Aubrey Beardsley, Max Beerbohm, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Sarah Bernhardt, Stella Patrick Campbell, André Gide, Lily Langtry, John Singer Sargent, George Bernard Shaw, Algernon Swinburne, Ellen Terry, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Verlaine, James Whistler, and Emile Zola.

His was fame by association. Simply being a gentleman was the mark he made on history.

Ross died suddenly, on October 5, 1918, at age forty-nine, probably from a heart attack.

In his will, Ross requested that he be cremated and interred in Wilde’s gravesite. This did not sit well with his next-of-kin.

Eliza Baldwin Ross had died in 1905 and the siblings were never close to their brother, so it was not until 1950, the fiftieth anniversary of Wilde’s death — the same year London County Council voted to place a commemorative plaque on Wilde’s Tite Street home — that Ross’s ashes were buried at Père Lachaise.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.